A dada creation of Teste, not the least chimeric, was to want to preserve art – Ars – purely by eradicating illusions about the artist and the creator”

Paul Valéry

(For a portrait of Monsieur Teste)

A Provisional Portrait

He was courteous, articulate, cultivated. At least, one would imagine so. He practiced understatement, liked humor as well as irony. He kept himself at a distance, always in the wings, and would not provide his opinion. On the edge of the circus of the vanities, here was the opposite of a man of letters, of a student of the mind.

The hell raisers of modern art made him the father of the revolution which redefined taste in the 20th century, without really knowing how he was influenced by Alphonse Allais and how similar he was to Ravachol or Kropotkine.

The fact is that this discreet, elegant man, practicing the subtle art of conversation instigated change. He was invited, celebrated in the most elegant circles, and people didn’t pay much attention to the crowd of roustabouts who, following him, invited themselves to the party.

After the patrons, came the institutions. In February 1977, for its opening, the Centre Georges Pompidou chose to celebrate him. This was a watershed event.It posed the question of the century: What is art? – And it chose to answer by brushing aside the heroes that one expected to find, Matisse or Picasso. With Duchamp, the Minister of Culture had to have faith, with twenty-five

With Duchamp, the Minister of Culture had to have faith, with twenty-five years still to go before the end of the millennium, to favor an art that he believed was liberal, anarchic, democratic, an art for all and made by all, and which answered therefore to the aims of an enlightened State which had known only to suffer an existing elite. Every man is an artist. Every gesture is a work of art. Every work of art can be anything at all.

The fact is that legions of slackers, hearing of artists out there without an oeuvre, without talent or profession, identified themselves with Duchamp, more or less. However, in their actions, their writings, their manifestations, the simplicity turned into misery; the subtlety, a heaviness; intelligence became stupidity; irony, slowness; allusion, crudeness, and finally the meticulous and mercurial method of “le marchand du sel” [Duchamp pseudonym] gave way to a plethora of productions by artists by the grosse, without spirit and without style.

Duchamp remained a silent witness to this phenomenon. He, who had carried on so little, written so little, and who had never taken credit for the result, with an amused smile, allowed the dream world of an avant-garde to become the palladium of fin de siècle societies.

There had been, without a doubt, a mistake about someone.

An Aristocratic Failure*

What was it exactly about the nihilism of Marcel Duchamp? What was the sense in his renouncing painting? By way of what did this transformation of values, this Nietzschian enterprise to which he attached himself, have some of the characteristics of the tabula rasa of the avant-garde at the beginning of the century?

By way of nothing, perhaps. The last of the decadents became, against his will, the first of the moderns.

* * *

Hannah Arendt saw and described that which in the first decade of the century bound modernity with totalitarianism. Contemporary artists during the First World War for the most part shared in “the desire, she said ‘to lose oneself’ and a violent disgust for all existing criterion, for all established powers. […] Hitler and those who were failures in life weren’t the only ones to thank God on their knees when the mobilization swept Europe in 1914.” The elite also dreamed of coming to terms with a world it considered corrupt. The war would be a purification for all, the tabula rasa of values which enabled belief in a whole new humanity. An entry into nihilism, for sure, was this rejection of a society saturated with ideology and bourgeois morality: “Well before a Nazi intellectual announced, ‘When I hear the world culture, I draw my gun,’ the poets had proclaimed their disgust for this ‘cultural filth’ and poetically invited ‘Barbarians, Scythes, Negroes, Indians, Oh! All of you, to the stampede.’

” This rage to destroy what civilization had produced as more refined, more subtle, more intelligent, “The Golden Age of Security” according to Stefan Zweig, but also to destroy this world which celebrated, in 1900, the triumph of scientific progress and humanitarian socialism, was shared by artists and intellectuals as well as terrorists from all sides, from the Nazis to the Bolsheviks. In the cafés of Zurich, Huelsenbeck and Tristan Tzara were mixing with, at neighboring tables, Lenin and the future trigger-happy political commissioners.

* * *

Still more recently, Enzensberger recalled some facts that France, sole remaining nation managing the arts in Europe, continues to ignore. “From Paris to Saint Petersburg, the fin de siècle intelligentsia flirted with terror. The premier expressionists called [it] the war of their wishes, just like the futurists […]. In large countries, the cult of violence and the ‘nostalgia for mud’ in favor of industrializing the culture of the masses, became an integral part of heritage. Because the notion of the avant-garde took an unfortunate turn, its first supporters would never have imagined...”

Let’s remember above all from Hannah Arendt the term “failures.” From Hitler, the regrettable candidate at the Academy of Beaux-arts in Vienna, to all those mediocre artists, poets and philosophers cultivating their resentment, failures hastened the twilight of culture.

Duchamp also, in a sense, was a “failure.” The feeling of failure – the idea of being a loser, a pariah, an outcast, a Sonderling or whatever leads a person to finding out at the age of fifteen or sixteen that they’re not in the “in” crowd – was most vivid. There was the social failure of being a notary’s son, an offspring of small-town bourgeoisie in a province that was already looked down upon on the eve of the First World War. There was the professional failure of his entrance examinations to the Ècole des Beaux-arts in 1905, which drove back the spirits of the young artist. There was the failure of the Salon des Indépendants in 1912, when his work was refused. So many wounds to narcissism.

But the most vivid failure remained family-related, when we see his ambition of becoming an artist thwarted by his own brothers, more talented than he. Jacques Villon was a good, sensitive painter and, more than that, an extraordinary engraver. Duchamp-Villon was a wonderful sculptor who, if he hadn’t been killed in the war, would have become one of the greatest artists of the century. Marcel, the youngest, was a menial, underpaid artist. How could he make a name for himself when his name was already taken?

Duchamp would be able in fact to serve as a perfect example to illustrate the argument, all the rage in the United States actually, that the youngest child is born to rebel. Put forth by Frank J. Sulloway, this argument tends to demonstrate on the basis of behaviors that the fate of great creators and reformers of society is dictated within the family dynamic by their birth order. While first borns identify in general with power and authority and have conservative personalities devoted to keeping their prerogative and resisting radical innovations, children born last weave a plan for turning the status quo upside down and often develop revolutionary personalities. “From this rank emerge the great explorers, the iconoclasts, and the heretics...”

In open rivalry with his older brothers, Duchamp would have been the prototype of the last born who, in order to dig his ecological niche, had the only alternative of radically upsetting the values advocated by his environment.

* * *

Even so, nothing about him was known to be resentful. Nothing more remote than the idea, common to intellectuals of the time, that individuals had to blend in with the masses to fulfill their destiny. Nothing about him would have been more disagreeable to consider than this comradeship in action of the masses which proposed to fell with violence the society it repulsed.

It was therefore by the love of irony and the daily practice of failing that he responded with his creative powerlessness. The homo ludens against the homo faber.

An accident of life, this feeling of being a failure – and that which was the result of it, his lofty distance from the inner circle – was leading him on the other hand to take note, at the start of the century, of a phenomenon which was elevating the universal. Few onlookers were yet alarmed by the situation, one without precedent in the venerable system of the beaux-arts. And Duchamp was one of the rare to acutely grasp that which others were refusing to admit: art – art such as we knew it, the art of painting, with its rules, techniques, and enslavement to style and schools, art with its status, social recognition, academies, salons, glory – had no reason to exist any longer. Art, an invention of the XVth century, had had its day…

What then had it meant “to succeed”? The previous generation had been able to believe in brilliant careers on the perimeter of respectable society. The studio of the painter who had “arrived” was part of the fashionable scene. But the fin de siècle artist was hardly more well-off than the colorful figure of the previous decades, uneducated, filthy, “stupid like a painter…”

Duchamp’s refusal never to let himself be seduced by the security of normal life and his scorn for the respectability and honors which accompanied this life were therefore sincere and very similar to the anarchic despair experienced by political explorers, by outcasts like Hitler. Without a doubt he didn’t escape, no more than any other, from an infantile proclivity for provocation. From the Indépendants to the Armory Show, he had not a few of these acts which recalled the violence of the time. His actual approach — so profound and so stubborn that it would define itself in the Large Glass, in the ready-mades, and later in Étant donnéswas of a wholly different nature. It was a matter less of shocking the bourgeoisie and destroying their culture than engaging himself in an intellectual adventure without precedent.

Anarchists, Dadaists, Surrealists and other dynamos of society: Duchamp was decidedly not of this group. Rather, his camp was that of the deserters. His departure for New York, at the beginning of the war, resembles Descartes’ departure for Amsterdam. To a cauldron of reflection, of daydreaming, far from the masses. Polite but reserved: he wasn’t there for anyone.

Max Stirner , therefore, rather than Nietzsche or Sorel. The idea of the unique

pupil in advance of the obsession. Nothing owed to anybody and nothing repeating itself. There wasn’t any need of “getting lost” because, in the world which he had entered, there was already nothing else to lose. He was the first to understand that he belonged to a world “without art,” in the same way one speaks of a world “without history.” When he began his work, the death of art had taken place. In this respect, Duchamp is a survivor, not a precursor. He wasn’t preparing for the flood, he was exposing the conditions for survival.

From Decadence to Dandyism

The elegance of a dandy instead of the feigned untidiness of an anarchist. The lack of distinguishing adornments. To pass unnoticed was the distinction. This avoided the worst blows as well as applause. It was an attraction to the strict, the rigorous, the stripped down – “austere” was the key word for Duchamp’s aesthetic, just the right tone in English flannel and tweed, enveloped in the wreath of a good cigar.

The distance he put between himself and his press was always very British. Every one of his talks, interviews, and writings was subject to: “Never explain, never complain.” There was no theory to justify himself, no excuse to excuse himself. Such reserve was immediately sufficient to disconcert a questioner, to discourage the curious, to confuse the scholarly.

The style of this period was also, among the enlightened ones in London, Vienna, and Brussels, about American functionality. Duchamp’s admiration for the quality of plumbing in New York was right up the alley of Adolf Loos; everything, like not tolerating the rancid smells of turpentine trailing about in the studios, was in accord with the architect of theMichaelsplatz, with his disgust for the pastry shops in Ringstraße. (The taste for industrial modernity, for every last technical comfort in improving a home, was already, right away, a trait of the decadent such as des Esseintes.) Nothing “dadaist” in any case, rather an exquisite education, confronting the trivialities of the time.

* * *

No, his admiration had gone instead, one could say, to Mallarmé, Laforgue, Jarry, Alphonse Allais. From his direct elders. From “countries” of Norman descent also, in that this concerned the last two. A nihilism well tempered. The line of the symbolist comet. It would be convenient to add, come to mention it, Huysmans – and Remy of Gourmont, another Norman – whom we think about very little.

From des Esseintes to the “Breather”

click to enlarge

10. Heinrich Hoffmann,

Marcel Duchamp, 1912

Is it possible that Hitler and Duchamp crossed paths in Munich, in the smoky cabarets of Schwabing or in the Festsaal of the Hofbrauhaus? It’s slightly possible. When Apollinaire wanted a portrait of Duchamp to illustrate Les Peintres cubistes, Duchamp chose Heinrich Hoffmann, the #1 photographer of Munich who had come to immortalize the work of von Stuck and of Hildebrandt, ill.10. This is

the same Hoffman who, eleven years later, would become Hitler’s personal photographer.

The photographs that he made of Duchamp, in the pose of a speaker with his mouth shut, were, it’s been said, influenced by Erik Jan Hanussen, the famous European sage, seer, and astrologer, who would have taught Duchamp the art of body language.

* * *

This reference takes us back to the ambiguous capital in which avant-garde artists and political adventurers plunged indiscriminately. In 1912, Munich had in effect become the Haupstadt, the European capital of occultism. The Gesellschaft für Psychologie, established by the official Baron

von Prell and the doctor von Schrenck-Notzing, was then in full swing and multiplying its exchanges with the spiritual underworlds in England, Italy and France. Nor did the heart of the modernist scene in Munich pass unnoticed by Stefan George’s circle. Moreover, in the plastic domain, along with vson Stuck and Marées, who carried the symbolist generation, one of the most celebrated painters in Munich was Gabriel von Max who painted portraits of sleepwalkers and spirits. His brother, photographer Henrich von Max, took photos of mediums in trance that Gabriel then used in his tableaus. Here, we notice a coincidence with the use of auras and halos which Duchamp tried his hand in with, for example, Portrait de Dumouchel. In 1907, the annual meeting of the Theosophical Society met in Munich and, between 1909 and 1913, the Mysteries of Rudolf Steiner were regularly played there. The great anthropology master, who in 1913 broke away to distinguish himself from the theosophy of Blavatsky, also promoted, during these years, conferences which were assiduously

attended by Klee, Kandinsky, Jawlensky, Gabriele Münter and Marianna van Werefkin. Did Duchamp listen in? If this disciple was reading so attentively, to the point where he made particular notes in Du spirituel dans l’art, wouldn’t he have been tempted to listen to the master? Did he go to see the Alchemy museum, in the future Deutsches Museum, with its cornues threaded one into the other like the sieves of the Large Glass? Without a doubt, and much more. It was in Munich in any case that he discovered the theme of his Grand Oeuvre and it was in a frenzy that he multiplied his approaches which would one day turn into the Large Glass : Virgin (No. 1), Virgin (No. 2), Mécanique de la Pudeur, Pudeur mécanique, Passage of the Virgin to the Bride, Bride.

* * *

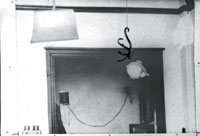

In search of a non-retinal art, capable of taking into account the invisible and its manifestations, Duchamp very naturally gravitated towards these “seekers” and found photography to be the new

medium which would permit him to materialize these new phenomena. In 1922, on Christmas Day, in the Brevoort hotel in New York, he wrote to his brother Jacques Villon: “I know a photographer here who takes photos of the ectoplasm around a male medium – I had promised to help him in one of

the seances and then got lazy but it would have amused me a lot.””

“Metarealism” had never really stopped fascinating the man who, in the “Pistons de courant d’Air,” had always meant to photograph ectoplasm.

It was this direction that I undertook to define in Duchamp et la photographie.

But the work, which appeared in 1977, had come too early. Enthusiasm for photography had not yet been born. Above all, in the Parisian climate, one wasn’t disposed to admit that occultism, theosophy and spirituality had fed the imaginations of modern painters more than Lenin’s work or the treatises of Rood or Chevreul. It would have to wait twenty-eight years and through a series of exhibitions that would begin in Los Angeles with The Spiritual in Artand culminate in Frankfurt with Okkultismus und Avant Gardein order to see this approach not only validated, but triumphing over others.

Much since then has appeared which reveals the immense influence of the irrational at the turn of the century on the birth of the avant-garde.

Two unpublished sources

A little more than twenty years ago, in 1977, I attempted to present the fertile ground of this vein without taking much risk and committing myself to it. To establish the approach of the avant-garde from its curiosity with the occult instead of its solidarity with the proletariat, this would have been too much of a shock for the doxaof modernism.

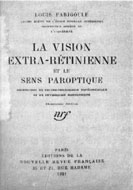

click to enlarge

11. The cover of the book by

Louis Farigoule, La Vision

extra-rétinienne et le sens

paroptique, 1921