“He rides penny-farthings, tandems, tricycles, racing bikes—

and when he dies at the end, he rides on his bike up a sunbeam straight to heaven, where he’s greeted by a heavenly chorus of bicycle bells.”

Dylan Thomas, Me and My Bike

Hamm: Go and get two bicycle-wheels. Clov: There are no more bicycle-wheels.

Hamm: What have you done with your bicycle? Clov: I never had a bicycle.

Hamm: The thing is impossible.

Samuel Beckett, Endgame

The bicycle offered unsuspected possibilities for the depiction of the raised skirt.

Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project

Introductory Observations

• The bicycle tends to arouse sexual desire or excitement.

• The bicycle is a traditional narrative usually involving supernatural or imaginary persons and embodying popular ideas on natural or social phenomena.

• The bicycle is commonplace.

• The bicycle is an unmarried man.

• The bicycle is a branch of metaphysics dealing with the nature of being.

• The bicycle gets you nowhere.

click to enlarge

Figure 1

Leonardo da Vinci, Bicycle Drawing,

Codex Atlanticus

(f. 133v)

In 1966 the monks of Grotto Ferrata, near Rome, discovered a sketch-apparently by Leonardo da Vinci, or by one of his pupils-depicting a bicycle-like machine complete with pedals, cogs, and chain mechanisms. (Fig. 1) The sketch was found alongside some caricatures, as well as some pornographic drawings. This scene could also be described as the collected works of Marcel Duchamp and Samuel Beckett.

Beside an Olympic skating oval, a world-class athlete (unable to ride outside because of the ice and snow) trains indoors on a real bicycle. The wheels, however, are set on soundless steel rollers: allowing the tires and rims to spin freely (at significant speeds) while keeping the bike and its rider stationary. We count this powerful, impotent spectacle as technology reversing technology (rollers unroll wheels), caught in a ceaseless loop of motionless motion. The avant-garde, too, can make modernity stand still-by moving it/stopping it yet again. Krzysztof Ziarek contends that “art is avant-garde to the extent to which it keeps unworking the technologization of experience by showing how, in order to reinscribe experience within the order of representation, it effaces historicity” (90).

The bicycle is very simple.

click to enlarge

Figure 2

Henry James

Leaving his fine suite in the Osborne Hotel, on Hesketh Crescent, feeling radiant and fresh after his hot morning bath, Henry James (Fig. 2) hopped on his bicycle and toured the sites of Torquay. Imagine it! Modernity takes shape in, and as, The Master’s black and yellow bruises-of which he was so proud.

Consider Renoir’s broken arm and Toulouse-Lautrec’s lonely, longing gaze at the velo-drome. (The pride of a sling; and legs too short to reach pedals?)

It sucks to write about bicycles. In that: it is much better to ride bicycles. Duchamp ride (Fig. 3): I would be doing lascivious things with my sprockets. Beckett ride (Fig. 4): I would be pedalling backwards and shitting on the saddle.

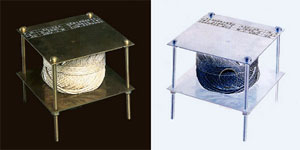

Artistical-historical (bland): the bicycle, the bicycle wheel (Fig. 5), and the objects of the bicycle are powerful symbols in the work of Duchamp and Beckett.

click to enlarge

-

Figure 3

Photo of Marcel Duchamp riding the bike

-

Figure 4

Samuel Beckett, drawing of the bike Molloy

-

Figure 5

Marcel Duchamp, Bicycle Wheel, 1913/1961

The presence of any technology that at once facilitates and complicates mobility is an interesting presence. Second thought: all technology simultaneously facilitates and complicates mobility. If the bicycle falls to this side of the modernist road then it lands in the ditch-water, if it falls to that side of the road it ends up in pasture. The modernist road has space for all mobilities: pedestrians, pedestrians on bicycles, pedestrians in motorcars, and even pedestrians in aeroplanes (emergency landings). But there is nothing more beautiful than a bicycle descending a hill by itself: ghost-rider.

The bike is a gender machine.

The modern is a technology machine?

click to enlarge

Figure 6

Image of F.T. Marinetti

In the climactic scene of F.T. Marinetti’s original Futurist manifesto-“The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism 1909”-Marinetti (Fig. 6) and his car (the beautiful shark) are famously flipped into the maternal ditch only to be born again in the metallic, celestial muck of industrial modernity. The newly baptised Marinetti, now a begrimed singer-apostle of all things dangerous, violent, machined, and frenetic, is literally tossed into his modern-technological epiphany by an older, slower mode of transportation. He recalls, “¡¦ I spun around with the frenzy of a dog trying to bite its tail, and there, suddenly were two cyclists coming towards me, shaking their fists, wobbling like two equally convincing but nevertheless contradictory arguments. Their stupid dilemma was blocking my way- Damn! Ouch! . . .” (20). The moment is significant, it seems to me, not as some elegiac snap-shot depicting the obsolescence of the bicycle and thus the triumph of the age of the automobile, but rather the exact opposite: Marinetti’s tale constitutes a vision of the stubbornness and presence (the stupid dilemma) of the bicycle itself. Marinetti’s manifesto, caught in a Keystone-cop-like loop, is indirectly documenting the very complexities, ironies, and even impossibilities of mobility in the modern moment. It shows the tragic-comic intermingling of technology with technology, and technologies with the modern subject. For me, the image of these wobbling, contradictory bicycles, despite the fact that they lack the throaty roars of Marinetti’s racing cars, is profoundly moving, because the bikes are curious, hybrid machines: both connotative of the past and yet apparently crucial (if annoying) fixtures on this future, avant-garde road.

Mikael Hard explains that “Facing a world of tanks and assembly lines, and using telephones and automobiles, ‘modern’ men and women were forced to differentiate the uses of technology from the abuses. The proliferation of the machine into ever more areas of social and economic life led to a need to interpret its meanings in a much more comprehensive way than in the past” (2). These transformative technologies of the modern period gave rise to new economies, new cities, new narratives of progress and anxiety and thus, necessarily, new bodies. The modern technologies of the plane, train, and automobile, for example, are not only devices that enhance the mobility of the modern subject, but also contraptions that transform the subject’s relationship to landscape and being itself.

click to enlarge

Figure 7

Alfred Jarry on bike

Figure 8

Marcel Breuer,

Wassily Chair, 1925

Bicycles are a central contraption in the tropics of the avant-garde. From Alfred Jarry’s bicycle obsession (Fig. 7) (he slept with his bike at the foot of his bed), to Picasso’s uncanny handlebar bull-hornism to Marcel Breuer’s Wassily Chair (Fig. 8), inspired by the tubular steel of his brand-new Adler bicycle, the machine haunts avant-garde experimentation. And this is particularly the case in the works of two exemplary avant-gardistes, Marcel Duchamp and Samuel Beckett. While there has been some critical attention paid to the place of bicycles in the texts of Samuel Beckett (notably Hugh Kenner’s work), there has been rather scant focus on the place of the two-wheelers in Duchamp’s corpus and nothing, as yet, that expressly pairs the two artists’ fascination with the bicycle as modern machine. What I argue in this essay is not only that the bike is a crucial facet in the experimental work of both Beckett and Duchamp (allowing one to glimpse significant aesthetic parallels across genres) but specifically that the bike, in their works, comes to represent a crisis of mobility in the modern moment. My contention is that, for both artists, this crisis plays out most tangibly in the fields of language and subjectivity so that the act of “being” in modernity, for Beckett and Duchamp, comes to be playfully linked to the problems of the modern self in interaction with technology. This essay explores the nuances of this interaction by interrogating the place of habit, language, desire, and daily experience in both the avant-garde and modern environments.

The Ride

Any study of the Duchampian/Beckettian bicycle swiftly transports a reader/viewer into the neighbourhoods of ontology, eroticism, bachelorhood, gender, myth and its relationship to the modern everyday. In using the symbol of the bicycle, Duchamp and Beckett illustrate the tragic-comic bind of the modern subject: the body is at once liberated by technology and yet also dangerously dependent on, if not indentured to, its power. (The same scenario exists, generally, for the artist in relation to technology; in relation to the technologization of both the artist and the art in modernity). For the modernist avant-garde then, the question is how to respond to the technological revolution of the everyday environment, which necessitates a grappling with the revelation that technology and reality are mutually constitutive. In other words, something lies beyond the simple bind of liberated/indentured in reference to modern art and the birth of the technological everyday. The avant-gardiste is clearly implicated, perhaps more explicitly than the non-artist, in the invention of the new: in the construction of his or her own unique aesthetic technologies. Therefore, the avant-garde artist becomes and is obsessed with the relationship between making and power; invention and history; progress and immobility. This suggests that the technologization of art and the artist is not just a one-sided narrative about cameras or cinema affecting painting and sculpture and novels. Rather, one sees-in Duchamp and Beckett most powerfully-that a toaster or a bicycle is also an art object, a site of desire, a mechanical conveyance, a glyph.

In this way, the technologization of art and the artist, plus the tragic-comic bind of the modern subject, is one way of discussing a competition of realisms: if there is no set trajectory for any given object then what results is either (or both?) experimental art or something like official status. The goal of the avant-gardiste may be to rethink history, rethink the experience of how one (a culture) gets to a confusion of signifiers, a multiplicity of meanings-and then to rework or restate or re-inscribe that otherwise blanked-out narrative, but to do so always provisionally (this can mean humour). The technologization of anything can therefore be the habitualization of anything, too, and so, in the hands of the experimental artist, the resulting “defamiliarization” is also always a new form of technology. Art restores order through disruption: we see that a bike can also “work” mounted on a stationary stool or that it does not need, as in Beckett’s Mercier and Camier, a chain to actually work. This implies that the avant-garde artist is declaring that no function is absolute and all functions are historically contingent. Perhaps modernity or modernism quite simply means: there is no going back, which then electrifies the present. Modernity (time) captures modernism (“time”) as modernism captures modernity. Modern art is implicated-as the Frankfurt school writers, most notably Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno, have already shown-in the workings of industrial culture and this is an aesthetic boon of sorts but also a dilemma.

Krzysztof Ziarek’s recent work The Historicity of Experience: Modernity, the Avant-Garde, and the Event, boldly challenges earlier theories of the avant-garde-including the important work of Peter Burger, Andreas Huyssen, Jurgen Habermas, and Rita Felski-by insisting that discussions of modernist experimentation must move beyond a simple art/life dialectic. Ziarek proposes that the avant-garde be understood not as something outside or “other” to everyday existence (avant-garde art merely transforming the everyday through representation) but rather as something directly temporal. In both Duchamp and Beckett, the bicycle often morphs into a corporeal, body-like presence-one that profoundly questions the stability of definitions of the modern, human subject. Duchamp’s and Beckett’s appropriations of the bicycle are also knowing disruptions of the everyday “sense” or use-value or art-value of the modern technological object and consequently serve to challenge more general, conventional (modern) notions of mobility. These two artists thus lend credence to Ziarek’s, as well as Kornelia von Berswordt-Wallrabe’s, theories of the avant-garde which stress that the classic avant-garde work tends to disrupt an object’s “stream of function” (von Berswordt-Wallrabe) and also then refigure the (ostensibly evacuated of history, transparent) everyday moment as a vital and fluid setting of the “Event.”

click to enlarge

Figure 9

Rover safety bicycle, 1885

Figure 10

célerièfre,1790s

The bicycle is a new genre, a radically unique object. It is at once a device that enhances human speed and propels the body through a landscape, and yet it is not so fast that the body is ever removed from the intimate motions of its immediate surroundings. The bicycle, for all its metallic presence, is a comfortable citizen of the back road, the country field, even the mountain pass. It has a relationship to the movement of the wheat as well as to the airy dips of the birds. As a nostalgia-contraption, it is predictably a locus for memories and childhood. As I discuss later on in the essay, the modern bicycle (the “safety” bicycle (Fig. 9), which very closely resembles our contemporary bicycles, was perfected around the late 19th century) has its technological roots in the 1790s’ French children’s hobby-toys called celerifere or velocifere (Fig. 10). From their beginning, then, bicycles have seemed to connote newness but also, perhaps more palpably, nostalgia and the vanished moments of youth. Cranking the pedals, or even just gliding down a hill, powers on the film of the past, a kind of Proustian recreation in which every new ride is always a tour backwards into time-lost. The bicycle is forever patient, too. Its simplicity is magnificent, how it waits against a shed, for example-not as a car sulks in a driveway or lurks beside the curb, but with a kind of Zen-like, friendly abandonment. The bike can look lonely, to be sure, but unlike other technologies of mobility (cars, planes, trains) it seems reconciled to melancholy; without ever being indifferent to, or utterly consumed by, its singularity. The poetics of the bicycle is infinite if only because-along with the complete entity known as “the bicycle”-each part of the machine (pedals, wheels, horn, handlebars, fenders, lugs, hubs, sprockets) resonates with particular, symbolic force.

The bicycle, importantly, is not just a double-sided object. It is multi-dimensional and it is therefore too reductive to state: “the bicycle has another side¡¦.” Yet the bicycle does exist-despite its halcyon glitter-as a protean modern object: it literally comes from (within) modernity. And quite possibly the bicycle can be seen as bringing modernity with it, pulling it out of the Victorian moment toward a late capitalist present. In the conventional cultural-historical narrative of European modernity-a tale that includes the spectacular entrance of planes, trains, and automobiles; the dramatic growth of metropolitan centres (and the elaboration of imperial networks); the birth of photography and cinema; not to mention the inventions of the telephone, typewriter and even tape-machine-the bicycle is a rarely-discussed, almost quaint participant. But for all its romantic-nostalgic energy, moving harmoniously through the ambience of sun-touched, pre-modern country lanes, the bicycle also helped create our modern/urban economies of mass consumption. Avram Davidson, in his short story “Or All the Seas with Oysters,” plots a brilliant, if idiosyncratic, evolution for the bicycle suggesting that safety pins are the larval and coat hangers the pupal stage of the machine’s gestation. What is fascinating about Davidson’s hypothesis is its mingling of the bicycle with other vital, but often overlooked, technologies of the modern. It seems to me it is precisely the apparent insignificance of the everydayness of the safety pin and the coat hanger that also gives the bike its power and poetics-all of these items are the overlooked, invisible dynamos of modernity.

The bike functions as a childhood emblem, then, but is emblematic too of Coca-Cola, Levi’s Jeans, MTV (Figs. 11, 12 and 13). Science historian Sharon Babaian explains that “The bicycle helped to forge the link between advertising and the mass consumption of luxury goods. It was the first expensive, non-essential product to be sold in such numbers-over 1.2 million bicycles per year where produced in the U.S. in the mid-1890s. Also, the bicycle industry was among the first to introduce annual model changes as a way of selling more products” (97). The bicycle, to use Raymond Williams’ term here, is “magical” but only as a revolutionary marketing tool-as a discovery, namely that within modernity a non-essential object could be engineered, mass-produced and sold for significant profit. The bicycle industry prefigured the automobile industry and thus anticipated the latter’s (soon to be more complete) construction and manipulation of appetites of mass consumption. And this was not only the case with the automobile industry but also with the aeronautics business. The Wright brothers, most notably, were originally a cycle firm. Moreover, Wiebe E. Bijker argues that by the turn of the century “Weapon makers, sewing machine manufacturers, and agricultural producers were only too happy to shift their production to bicycles” (32). And so the bicycle is a key protagonist not only in the narrative of mass transportation but also, and more expansively, in the drama of modern marketing, everyday consumption, modern technology, and the diversification of industrial technology.

The bicycle, as both modern symbol and modern technology, is hence deeply embedded in a grander narrative of progress and use-value. To some extent the avant-garde is the manifestation of the retooling of such narratives-a practice of functional dysfunction and, like the everyday itself, much of the avant-garde’s power (force) resides in the play with context and referentiality. Ziarek writes.

Duchamp’s urinal or bicycle wheel ¡¦ stand the ordinary on its head, disconnecting everyday tools from their functional context and, thus, bringing into the open the invisible regulative force with which technicity forms modern being . . . In other words, the concept of the ordinary as immediate, as a place of common knowledge or a sphere of prelinguistic experience, sheltered from the influence of technology and mass culture, has to be called into question. The ordinary is already mediated, it is enframed technologically and functions as a font of availability, as resource or Bestand. (113)

click to enlarge

Figure 14

Photograph of Duchamps

studio showing the

Fountain (1917),

1917-18

Figure 15

Photograph of Duchamps

studio showing the

Bicycle Wheel

(1913-14), 1917-18

The urinal or the bicycle wheel (Figs. 14 and 15) are revealed (as opposed to made) by the avant-gardiste as displaced, even suspended, artefacts of the everyday. They are recontextualized and thus undergo a number of-by now very well documented-changes. First, their use-value is confused as soon as they are “noticed” as art. Part of the enduring aesthetic, even revolutionary, energy of the Duchampian urinal, for example, lies in the crisis it creates for the viewer, forcing one to wonder as if for the first time: “what is a urinal? what is an art object? do I associate art with piss? do I now piss in art?” Perhaps the urinal never asked to be viewed before either. The avant-garde’s use of everyday objects is necessarily a radical play with the technologization of sense, use-value and function. Berswordt-Wallrabe explains that Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel “had its roots in the artist’s ability to distance himself from the intended utilitarian purpose of the object and thereby to interrupt the existing stream of function, diverting the object or parts of it into an entirely different stream of function” (19). The “other dimensions” of the everyday object are all contained within the art object itself; it is the context-shifting that here brings them into view. (Uselessness, nonsense, suspended function, purposeless play-these are, incidentally, the adjectives also applicable to the characteristic bodies and modes of Beckett’s fiction.) If the everyday object is removed from the everyday (or at least becomes embossed on the template of the everyday), is the same-but in reverse!-true of the art itself? In other words, is part of the crisis that the avant-garde inaugurates that of necessarily returning art to the setting of prosaic, modern being? A curious “cycle”?

Beckett 1

In considering the richness of Samuel Beckett’s numerous bike riders, Hugh Kenner famously surmises in his 1962 monograph, Samuel Beckett: A Critical Study, that Molloy, Moran, Malone, Mercier & Camier et al are representations of “Cartesian Centaurs” (121). Kenner understands this centaur-subject to be guided by rational intelligence yet ever and necessarily obeying the mobile, irrational wonder of the bicycle’s own motion and desire. The Cartesian Centaur is therefore a compliment of mind and body, but also and most importantly of body and machine: “Cartesian man deprived of his bicycle is a mere intelligence fastened to a dying animal” (124). The Beckettian bicyclist, however hopelessly, utilises the bike as a substitute body: one that, if not deathless, at least presents the illusion of delaying or denying mortality.

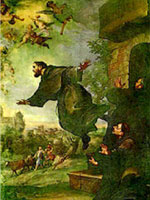

click to enlarge

Figure 16

French childrens

late 18th

Century hobby horses

Figure 17

cherubim riding on similar contraptions

Kenner’s Centaur is also interesting because, as aforementioned, the earliest known bicycles are thought to have derived from French children’s late 18th Century (1790s) hobby horses (Fig. 16). These proto-bikes were unsteerable and pedalless (very Beckettian attributions!), but equipped with two wooden wheels which would allow a rider to propel (push) themselves with their own leg power, or easily coast down a hill. The celeriferes bear an interesting resemblance to certain medieval church iconography in which cherubim and seraphim are shown riding on very similar contraptions. (Fig. 17) These early bicycle images suggest a complicated, if curious, history for a poetics of the modern bicycle. The self-propelled, wheeled vehicle is-from its earliest representations-aligned with the sacred, and specifically with images of ascension and purity. At the same time, these medieval proto-bikes are of course excessively, necessarily earthly machines: the wheels themselves most obviously requiring the stability of the ground, the real. The fundamental tension of the bicycle, perhaps, and one that Beckett exhaustively mines, is that which exists between its angelic and corporeal symbology: it strives dynamically upward and yet is, unfailingly, a mortal vehicle. The discrepancy between virtuous potential and practical, ignominious fact fully articulates the tragic-comic grey space of Beckett’s fiction.

The bicycle first appears in Beckett’s work in his early 1934 collection of short stories, More Pricks Than Kicks. In the “Fingal” tale, the young lovers Belacqua and Winnie head off from Dublin for a romantic afternoon in the country. Their relationship is decidedly cool and characterised by defensive, droll repartee that is further ironized by the arch, omniscient narration. To confirm the subversion of the romance story, Belacqua is inflicted with “impetigo,” the knowledge of which compels Winnie (post-smooch) to thoroughly clean her mouth. And so it is not surprising-in this context of diseased, contaminated “romance”-that the destination of the love-jaunt in the country soon turns out to be the Portrane Lunatic Asylum (“she having a friend, he his heart, [there]”) (26).

On their way, however, Belacqua discovers something in the grass: “They followed the grass margin of a ploughed field till they came to where a bicycle was lying, half hidden in the rank grass. Belacqua, who could on no account resist a bicycle, thought what an extraordinary place to come across one. The owner was out in the field, scarifying the dry furrows with a fork” (27). The context of Belacqua’s discovery-especially in light of this being the first appearance of a bicycle in Beckett’s work-is significant in that the bicycle is riderless. The bicycle, lying abandoned in the rank grass, cannot help but be read as a kind of object counter-part to Belacqua’s own melancholy subjectivity. In particular, Belacqua’s interest in the bicycle is described in relation to his desire: he could, on no account, “resist” a bicycle. In this way, too, the bicycle is the clear, if wry, substitution of or for Winnie and, indeed, the scene mimics the encounter just previously in which the two lovers had been lying on the grass. What is clear here is that the bicycle is Belacqua’s discovery, and so his relationship to the machine is vaguely illicit and, at the very least, works to further his own solitude. Janet Menzies points out in her discussion of the scene that the encounter of the bike is “faintly disturbing” (99). One reason for this uncanny feeling is presumably that the bicycle and Belacqua seem to become indistinguishable. “Fingal”‘s narrative power rests not only in its rather flawless balance of aloof omniscience with caustic dialogue, but also with the mysterious anxiety that the discovery of the bicycle produces. The bicycle takes on a kind of “being” and seems to wordlessly, eerily compete with the superficial intentions of the love story.

This eerie competition is compounded by Belacqua’s developing connection, almost a homosocial alliance, with the bicycle owner and, of course, with the bike itself. The narrative makes it quite clear that Belacqua and the bicycle owner are aligned on the level of their shared masculinity. They both agree, for example, that “it needed a woman to think [the logistics of efficient travel] out” (28). Moreover, as Belacqua and Winnie move away from the man, we read that “Belacqua could see the man scraping away at his furrow and felt a sudden longing to be down there in the clay, lending a hand” (28). This moment happens two short paragraphs after an extended allusion to Hamlet: “The tower began well; that was the funeral meats. But from the door up it was all relief and no honour; that was the marriage tables” (28). If Belacqua is vaguely figured as the dispossessed son here and the bicycle owner as the ghostly father-figure, then Winnie is by default or implication a representation of Gertrude. Regardless, “Fingal” is to some extent a condensed and energetic reworking of the Hamlet themes of madness, diseased desire, and homosocial longing. Indeed, Winnie is evidently also the Ophelia representation here as she and Belacqua seem to be perpetually replaying a modernist version of the get-thee-to-a-nunnery exchange.

As Belacqua and Winnie sit and watch the “lunatics” taking their recreation on the grounds of the asylum, the bicycle owner (apparently an inmate of the asylum himself) comes running towards the lovers. “Belacqua rose feebly to his feet. This maniac, with the strength of ten men at least, who should withstand him? He would beat him into a puddle with his fork and violate Winnie” (30). Beckett’s narration is so comically convincing here because it completely undermines all the “masculine” labour that has previously sought to align Beckett and the bicycle owner. Now Belacqua is positioned less as a modernist Hamlet hero and more as a pathetic-neurotic anti-protagonist. Importantly, the bicycle owner not only runs innocently by the lovers but-crucially-leaves his bicycle behind him, unattended in the grass: “the nickel of the bike sparkled in the sun” (31). The alliterative, consonance clucks of the k’s alone in this sentence work to distinguish the bicycle as a glorious, exquisite signifier (and align it with Belacqua’s own clicky appellation). Thus Belacqua-all things working in his favour-manages to pass Winnie off on her friend Dr. Sholto while he promises to rendez vous with them “at the main entrance of the asylum in, say, an hour” (31). Belacqua, of course, takes a route back to the resplendent machine:

It was a fine light machine, with red tires and wooden rims. He ran down the margin to the road and it bounded alongside under his hand. He mounted and they flew down the hill and round the corner till they came at length to the stile that led into the field where the church was. The machine was a treat to ride, on his right hand the sea was foaming among the rocks, the sands ahead were another yellow again, beyond them in the distance the cottages of Rush were bright white, Belacqua’s sadness fell from him like a shift. (31-2)

Only the interaction with the bicycle seems to allow the narrative to mobilize, so to speak, its most romantic descriptions. Belacqua’s ride literally shakes off his melancholy and it is quite clear that the bike represents both a metaphysical escape from his sadness as well as a physical flight from Winnie. It seems significant, too, that Belacqua’s depression falls from him like a shift, as if the action of the ride is also sexual or (perhaps less carnally) at least cleansing and perhaps feminizing, too-returning him to a first, innocent, and naked moment. Belacqua, of course, never keeps his promise with Winnie and Dr. Sholto and the climax of the story depends on his callous departure. Sholto and Winnie, left waiting, are forced to inquire of another bicyclist entering the asylum if he has seen a person resembling Belacqua: “‘I passed the felly of [that description] on a bike’ said Tom, pleased to be of use, ‘at Ross’s gate, going like flames.’ ‘On a BIKE!’ cried Winnie. ‘But he hadn’t a bike.'” (34). The “going like flames” is a hilarious insertion that contrasts even more comically with Winnie’s slapstick, higher-case exclamation. Her position here, terribly outside the narrative asides, is now confirmed and her innocent “but he hadn’t a bike” comment renders her character charming but slow. Belacqua’s escape is, indeed, complete as the tale closes by revealing that he was “safe in Taylor’s public-house in Swords, drinking” (35). The bicycle, in its first Beckettian mode, is truly a remarkable bachelor’s conveyance: a reliable escape machine, something that can be literally discovered in the grass.

Duchamp 1

“Fingal” can be read as a type of onanistic bachelor’s allegory and, as such, it has (of course!) much in common with Marcel Duchamp’s corpus-especially his celebrated, pioneering ready made Bicycle Wheel. In a 1955 letter to his acquaintance Guy Weelen, Duchamp writes:

My recollections as to the apparition of a bicycle wheel mounted on a kitchen stool in 1913 are too vague and can only be treated as a posteriori reflections. I only remember that the atmosphere created by this intermittent movement was something analogous to the dancing flames of a log fire. It was as if in homage to the useless aspect of something generally used to other ends. In fact, it was a ready made “before the event” as the word only came to me in 1914. I probably accepted the movement of the wheel very gladly as an antidote to the habitual movement of the individual around the contemplated object. (Letters, 346 June 26).

Like Beckett, Duchamp reveals the bicycle (or its components) as a clearly seductive object. If Belacqua’s bicycle scintillates like nickel and allows him to “go like flames,” then Duchamp’s 1913 Bicycle Wheel, too, adopts the erotic, hallucinatory rhythms of a log fire Importantly, Duchamp’s recollection of the creation of this ready made is a characteristically paradoxical mixture of both elucidation and mystification. It is clever as well as strategic that Duchamp refers to the Bicycle Wheel’s construction as an “apparition.” Duchamp casually tinges his entire recollection of the Bicycle Wheel’s construction with the qualities of serendipity, not to mention ethereality. Also, that he offers that the sculpture was “a ready made ‘before the event'” is an audacious and sly manoeuvre in that Duchamp is actually depicting himself as anticipating himself. A fascinating confusion results because the Bicycle Wheel piece, on the one hand, seems to merely “appear” while, on the other, Duchamp’s sole responsibility as the magician behind its fantastic apparition is implied. Regardless of Duchamp’s brilliant, self-mythologizing prose, the letter also reveals that the Bicycle Wheel constitutes a sort of homage to “the useless aspect of something generally used to other ends.” This statement, in miniature, is a provisional definition for all experimental projects in that it indicates the fraught, necessary tension that exists in the avant-garde between function and dysfunction.

Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel is dependent on its general function, presumably, as a device in a larger piece of machinery that conventionally facilitates human mobility-a bike. It is also dependent, as a seeable piece of art, on highlighting the transparency of that original function while at the same time asserting or proposing an alternative (dis)application (here a wheel mounted upside down in a stool.) What exists between the function and dysfunction are the inter-workings of the everyday (the minutiae of cultural history): the particularly intimate negotiations between objects and subjects. Nothing, it seems, is outside history, nothing is entirely bland, nothing is beyond power. Here modernity is the discovery that the human subject exists no less arbitrarily or perversely than its surrounding objects. Technology-in all its forms-is thus the dynamic crisis of human uselessness. Both Beckett (especially in Molloy as we will see) and Duchamp mobilize the bike to highlight the tragic-comic complications of this critical ontology.

Yet in Duchamp’s brief letter to Guy Weelen it is the last sentence that is arguably the most compelling. Duchamp states that, “I probably accepted the movement of the wheel very gladly as an antidote to the habitual movement of the individual around the contemplated object.” The habitual movement around the contemplated object could refer to the everyday activity in a kitchen. If so, then the wheel is arguably an anti-everyday object (anti-domestic and anti-materiality, on one level). In this way, and despite Duchamp’s characteristically oblique, ingenious phrasing (he “accepted” [“accepte”] the movement of the wheel), he seems to be indicating that the spinning wheel directly disrupts conventional aesthetic viewing patterns. While the bicycle wheel spins on top of a stool it is presumably fixing the viewer in one location. Duchamp implies that the Bicycle Wheel is an alternative sculpture because it is kinetic but also because it seems to invert the object/subject aesthetic relationship. In other words, there is a startling suggestion that the Bicycle Wheel is, in fact, looking back at (contemplating) the viewer. This looking-back-at-ness is not so much a result of a personification of the art-object, but rather more generally of how the Bicycle Wheel (and all ready mades) draw(s) attention to conventional modes of viewership and reception. More importantly perhaps, Duchamp links “contemplation” with mobility and habit.

Beckett, too, in his later Texts for Nothing, finds in the bicycle wheel specifically a metaphor for the repetitive, often futile, work of memory. He writes, “What thronging memories, that’s to make me think I’m dead, I’ve said it a million times. But the same return, like the spokes of a turning wheel, always the same, and all alike, like spokes” (128). Duchamp’s letter to Weelen continues on to detail a kind of collision of movements-a clash of mobilities- within the field of vision. Herbert Molderings contends that, “The bicycle wheel with its fork pointing down and mounted on a stool is fundamentally a chronophotographic sculpture voiced in the language of the Futurists: a sculpture of movement” (150). The Bicycle Wheel, if not entirely “futurist,” is unarguably concerned with the seeing of movement (as opposed to a merely futurist-like glorification of the mobile). Moreover, for Duchamp, viewership and reception are also forms of mobility just as the new, ready made Wheel derives its force from a type of counter-movement. According to Duchamp, then, his ready made sculpture is, at once, an entrancing, lulling spectacle comparable to the dance of flames on a log and yet also an object that resists (is an antidote to) habitual forms of aesthetic contemplation.

click to enlarge

Figure 18

Man Ray, The Gift, 1921

Figure 19

Marcel Duchamp,

Bottle Dryer, 1914

But the Bicycle Wheel is only, it seems to me, half of the aesthetic story. The wheeled-sculpture depends crucially on its stool mounting. The Bicycle Wheel is hardly a ready made in the sense that Duchamp’s Bottle Rack or Snow Shovel are: these items qualify as “toute-fait” in that they require no elaborate aesthetic manipulation or intervention. The Bicycle Wheel, unlike its counterparts, does not merely await selection, it also demands assemblage and, to some extent, physical contact (spinning the wheel) from the viewer. The Bicycle Wheel is, above all else, a bizarre object because it defamiliarizes the everyday by blending typically aloof components of the everyday with each other. The avant-garde formula here is to add mundane objects (common technologies but technologies commonly not associated with each other) together in order to equal the experimental aesthetic machine. (Man Ray’s “Gift,” (Fig. 18) for example, a household iron with nails solder on its smoothing surface, would also be apposite here.) If the Bottle Rack (Fig. 19) is avant-garde because it is a prosaic, overlooked object that is then chosen, inscribed, and signed, then the Bicycle Wheel is radical both because it is not fully a stool (and the stool is not fully a bicycle) and because it now demands aesthetic contemplation. The Bicycle Wheel is still highly “artistic,” therefore, in the sense that it spotlights both the artist’s cleverness and his delectation (though Duchamp always and emphatically denied that his “selections” were aesthetically or “retina-lly” motivated). The Bicycle Wheel also introduces (at least) a double crisis: the viewer is incited to wonder not only ‘what is art?’-as is the case with the other ready mades-but also, more simply, ‘what is this?’

Significantly, on the level of practical everyday objects, the Bicycle Wheel is a ridiculous and even useless machine: a subverted stool and a corrupted bike. Like the depictions of bicycles we discover in Beckett’s Molloy and Mercier and Camier, for example, Duchamp’s bicycle is a playful emblem of the comedic failure of (again, at least one kind of) mobility. A viewer, accustomed to that “habitual movement around the contemplated object,” is now fixed with a machine that moves elegantly, entrancingly, yet never, finally, goes anywhere.

The maddeningly enclosed, even intensely self-regarding, circuit of contemplation that Duchamp’s Wheel inaugurates is arguably but another bachelor apparatus, specifically what we might call an onanism process. Calvin Tomkins, Duchamp’s English language biographer, points out that, as a verbal or visual image, the machine-onaniste [Duchamp’s phrase] comes up again and again in Duchamp’s work: . . .Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel and his obsession with circular forms; his optical machines whose spiral patterns oscillate in a pulsating, back-and-forth rhythm; his invention of Rrose Selavy, a female alter ego; and the very fact that in the Large Glass the unfortunate bachelors never do manage to strip bare the willing but imperious bride-all these can be seen as signposts in the life cycle of the solitary male” (276).

click to enlarge

Figure 20

Marcel Duchamp,

Note from the

Green Box (1934)

It is not clear whether Tomkins is intentionally punning on the “life cycle” of the male, but the Bicycle Wheel (with its erotic allure and circuit) is certainly symbolic of Duchamp’s dual fascination with the cyclical nature of delay and desire. Indeed, Duchamp’s Green Box catalogue refers enigmatically to the “litanies of the Chariot: slow life, vicious circle, onanism” (Fig. 20) (np). The bio-mechanics or bio-morphism are incorporated by the symbol of the wheel (the vicious circle) and thus also by both the body and desire.

And beyond the particular narrative that highlights the desiring, self-gratifying bachelor, there is also an extra-textual and aesthetic onanism potentially at work. Amelia Jones, in her shrewd study of Duchamp’s relationship to postmodernism, suggests that Duchamp himself has come to stand-in for the ready mades, and vice versa. Postmodernist criticism has thus created a kind of art historical fantasy in which the object replaces the artist-and, in so doing, installs Duchamp as self-generating, ever-fecund patriarch. She writes, Duchamp’s significance as originating father is generally seen to be identical to the significance of the readymades in relation to postmodernism. As mass-produced objects rendered as art only by reference to their authorizing function, Duchamp, the readymades become Duchamp as we know him today. As paternal, theological origin, Duchamp is the readymades and the ‘readymade Duchamp’ comes to signify postmodernism. (8)

Thus Duchamp’s objects are always conflated with Duchamp’s subject-position and presumably every reading of the Bicycle Wheel, for example, is also a reading of a complex metonym for the artist himself. The crisis is most fascinating then in reference to the re-aura-ification of the work of art by way of granting a distinct “author” to an otherwise nameless object. Part of the force of Beckett’s and Duchamp’s mobilization of these everyday technologies lies in the way they draw attention to the radical anonymity of the objects’ function. Thus, if Jones is correct in asserting that the ready made and “the Duchamp” have become interchangeable, it is perhaps a result of a collective refusal (anxiety) to grant objects any serious, non-human identity and presence. Both Duchamp and Beckett illustrate that the everyday object is interesting precisely because there is no certain boundary between it and the human subject.

As Tomkins implies above, the Bicycle Wheel is also connected to Duchamp’s invention of his female alter ego, Rrose Selavy. And indeed, the Bicycle Wheel is a particularly Selavy-esque technology-a kinetic sculpture that can also be seen as an impish reference to women’s knitting wheels of the past. The bicycle is an important technology for modernity not just in the context of its inspiration of advanced capitalist marketing strategies, which were then adopted by numerous other companies, but also in terms of women’s emancipation and the New Woman specifically. As Patricia Marks elaborates, “These New Women, who wanted all the advantages of their brothers, asked for education, suffrage, and careers; they cut their hair, adopted ‘rational dress’, and freewheeled along a path that lead to the twentieth century” (1). Bicycles allowed women to not only escape the home and the obligation of the knitting wheel, they also crucially allowed women to be mobile and to be so without either a male or female chaperone.

The bicycle was such a new technology that its effects on both the male and female body were a source of serious and continual concern. The Penguin Book of the Bicycle reports that, “Up till 1893 doctors had maintained that cycling was a notorious cause of illness. The medical profession worried deeply about ‘bicycle walk,’ ‘bicycle heart,’ or, most dreaded of all, kyhosis bicyclistarum, ‘cyclist’s hump,’ caused by strenuous pulling on the handlebars” (126). For women bicyclists, medical practitioners (including woman doctors) worried that bicycle riding would exhaust female riders’ vital, maternal energy and thus complicate, or even prohibit, child-birth (Marks, 174). The action of pedalling, in this instance, is a kind of anarchist threat to all normative gender and social systems. If the Bicycle Wheel is in fact a Rrose Selavy (might then Rrose’s wheel become “Roue C’est La Vie”?) machine, then it is a bachelor apparatus ironized and nuanced by the contexts of both the gendered history of bicycle riding as well as that of domestic labour and public culture.

click to enlarge

Figure 21

A French poster by

Jules-Alexandre Grun for

Whitworth Bicycles, “Quelle

Machine Acheter?”, circa 1897

Figure 22

A French advertising

poster by Edouard

Corchinoux for Cycles

Meteore, circa 1920

The modernity of the bicycle is inseparable from the advancement of women’s rights, but it is also directly linked to the objectification of the female, particularly as it figures a classical, feminine, mythic beauty as the ample spokes(!)-woman for this new technology. As if an extension of the early church-window cherubim straddling wheels of fire, the representations of women in early (late Victorian) bicycling advertisements are also strikingly iconographic. This lyrical idealization of the woman is an interesting contrast with the practical concerns for women’s safety, health, and sexuality. The woman, refracted through the medium of the bike, is both the angelic metonym for airy travel but also the latent threat of what that freedom might inspire. Consider the numerous advertisements collected in Jack Rennert’s 100 Years of Bicycle Posters in which turn of the century (late 1800s) women are depicted as bewinged, sylvan, naked, sword-wielding, flying, shield-carrying, wind-tussled beauties. (Figs. 21 and 22) One poster in particular, an 1897 Paris ad for Catenol bicycles, reveals a voluptuous, completely naked woman sitting on the edge of a stone well. The bucket mechanism for the well is apparently driven by a bicycle crank and pedal system. The woman is staring out at the viewer giving the “evil eye” hand-signal while her right ankle is chained to the well. The poster reads, “La Verite Assise!!!” or “the Truth is Seated/Established.” This bride stripped bare here reveals the bizarre, ever-erotic connotations of the bicycle. Perhaps because of its own mechanical nakedness, the bicycle is to some extent always obscene and thus connotative of erotic excess. That the woman here, with her simple but queenly(16) tiara showing an impish, cartoony smiling face in its centre, is literally chained to the “well of truth” is a useful reminder that the bike is unavoidably-if comically!-connected to both desire and mobility.

Beckett 2

click to enlarge

Figure 23

Cover of Molloy by Samuel Beckett

The Beckett novel in which bicycles (and thus desire at work as mobility) play the most significant role is Molloy (Fig. 23), the first section of Beckett’s celebrated trilogy. Molloy opens in a motherless mother’s room. The eponymous character tells the reader that a man comes every week to “take away the pages” (7). The novel is hard not to read as an allegory for the plight of the neurotic artist: boxed in his mother’s chamber, the writer can’t really be certain of anything. Molloy, however, despite this claustrophobic opening, is a grandiose journey story, or journey stories (Molloy is looking for his mother; Moran & son are looking for Molloy), which document(s) not (by now a Beckett critical cliche) the futility of progress but rather something entirely antithetical: the fact that motion, the need for mobility, is inevitable and intimately connected with both language and being. The Trilogy, and Molloy most abundantly, is a meditation on the inevitability of action, especially as action becomes confused and conflated with both dwindling speech and decaying physical presence. J.D. O’Hara reveals that, “Molloy progresses, so to speak, from one-legged bicycling at the start, and is about to set out on crutches at the end; Malone begins as a bed-ridden octogenarian and ends dead; the Unnamable, a weeping egg, conjures up surrogates who hobble on crutches or exists armless and legless in a jar” (10). For Beckett, it appears that all mobilities (verbal and physical) are complicated by their intimate dependence on each other, which thus serves to produce other competing, interactive binaries: silence and speech, for example, or death-rattles and long novels.

Visual artist Stan Douglas notes this unceasing energy in Beckett’s work and observes that, “Characters and voices in extreme situations of solitude seem to await silence or death but in fact seldom come to rest and even more rarely stop talking; persistent in their desire for something not yet said or not yet done” (11). Beckett’s characters, Molloy as an exemplar, are hardly despairing, existential party-poopers, but rather bizarrely dynamic entities: bodies and languages that utterly refuse to either rest or shut-up. Considering this manic context in Beckett’s work, the bicycle machine is an apposite device that condenses and contains his preoccupation with both mobility and speech.

Molloy appears to be uncertain of almost everything in his world other than his affection for the classic two-wheeler. Like Belacqua in “Fingal,” Molloy comes upon a bicycle as he ventures outside. Ludovic Janvier states that, “The bicycle, then, is an instrument of derisory super-power, of cheap super-lightness, to which the ‘hero’ trusts his destiny” (47). It seems to me that these Beckettian “bike-discovery scenes” are comparable to the thrilling moment in Cervantes’ Don Quixote in which the narrator states that Quixote, “t[ook] whatever road his horse chose, in the belief that in th[at] lay the essence of adventure” (36) The bicycle, like the horse, embodies adventure and whimsy but also, and crucially, the power of both destiny and chance to shape being. Of course Molloy is on crutches, and so his ride is spectacularly distinct (even Quixotic?) from Belacqua’s going-like-flames style. This fact alone suggests the serious chasm separating Beckett’s original bachelor rider from his Trilogy-era one. While Belacqua is literally able to make his fiery escape to the local pub, Molloy is much more entangled with the technology. Molloy explains, “This is how I went about it. I fastened my crutches to the cross-bar, one on either side, I propped the foot of my stiff leg (I forget which, now they’re both stiff) on the projecting front axle, and I pedalled with the other” (17).

To complicate matters further, Molloy’s bicycle happens to be chainless and one with a free-wheel-essentially an impossible machine. As Molloy becomes the bicycle, so to speak, the resulting visual (M. lashed to his self-propelled, chainless vehicle) is like a mirror of Beckett’s own appropriation of (self-fastening to) impossible language. In other words, as Molloy integrates with a superbly faulty machine so too does Beckett-throughout the Trilogy-blend with a severely and increasingly restricted (chainless) language, character and plot. Molloy thus sabotages the familiar technology of the bicycle by making it interchangeable with his own being. Molloy is a cyborg body (propped up with crutches, steel, and rubber) but also, and more simply, just a tangle of prosthetics: an ironic symbol of motion. Molloy’s impossible “mobility” is dependent, therefore, on an array of mobility-technologies and, as he is the symbolic author stand-in, his strange “mobility” is necessarily and always about the (im)mobility of writing and reading, too. So, Molloy’s technological reliance is a self-conscious staging of the avant-garde author-function-wanting and needing to move through an environment that is either hostile or indifferent to action.

After Molloy describes his mounting of the bicycle he becomes hilariously, beautifully absorbed in a description of his machine. He sighs, “Dear bicycle, I shall not call you bike, you were green, like so many of your generation. I don’t know why. It is a pleasure to meet it again. To describe it at length would be a pleasure. It had a little red horn instead of the bell fashionable in your days. To blow this horn was for me a real pleasure, almost a vice” (17). Molloy’s disquisition on the pleasures of bicycles (and horns) is then disturbed by his recollection of his true subject: that of “her who brought [him] into the world, through the hole in her arse if [his] memory is correct. First taste of the shit” (17). Again, as in “Fingal,” it is clear that the bicycle is inseparable from the question of gender-and specifically “woman.” As Molloy arrives in the world through the hole in his mother’s ass, it is a further reversal of traditional (in this case, biological) “technologies.” Molloy is literally a piece of shit, on the one hand, but he is also (though this is no doubt scant consolation) a resplendent symbol of inverted modern “production.” His bicycle exists in some ideal, pluperfect past while Molloy is left to narrate that past with, it seems, the “first taste of the shit” still (always) on his tongue. Thus Molloy’s “productions” are always, like his own birth, scatological “issues.”

Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, in their own machine-obsessed text, Anti-Oedipus, wonder about the function of the bicycle in Beckett’s work, specifically asking what relationship the bicycle-horn machine might have with the so-called mother-anus machine (2). If, as they suggest, that “There is no such thing as either man or nature now, only a process that produces the one within the other and couples the machines together” (2) then the Beckettian avant-garde technology is located in that place in which function becomes actively blurred with form and vice versa. One can ask what things do in this scenario but one cannot ask what processes produce because they are always in flux. The avant-garde’s stake is therefore in the ing of the verb. Jean-Francois Lyotard contends that technology is traditionally founded on principles of optimum performance, and specifically that technology can be understood as a drama of efficiency (Postmodern Condition, 44). Technology is a game of mobility, a contest of speeds, in this reading: power is speed, finally. Powerful technology is anything therefore that does not complicate or obtrude motion. Infinite process (that which is not ever resolved-that which is always in the middle of doing something more) is hedonistic and even paradoxically unproductive as it looks only to be intent on motion, not resolution. The in-flux processes, the body technologies, in this case, consist of Molloy and his mother who, as he describes it, are thoroughly malleable as identities. Molloy is finally unsure, as he says, whether he is the father or the son in the relationship and even whether his mother is “Ma, Mag or the Countess Caca” (18). And when Molloy moves into the terrible but uproarious description of his improvised form of communication with his deaf mother (he has had to, he tells us, resort to knocking on her skull to get a yes or no answer) then the absurd possibilities of bodies is confirmed. Beckett does not, of course, endeavour to detail human potential on a sentimental scale, he instead illustrates the potential for subjectivity to be no different than objects. A mother, to some extent, is discovered as merely a machine you have to knock your knuckles against to “make work”; a son is a ridiculous prosthetic apparatus; while the bicycle itself is the ideal by which human potential is measured. Here the lyrical, human technology trumps the human altogether.

As Molloy sets off on his fantastic but everyday machine he, like Mercier and Camier, is soon stopped by a policeman. The convergence of Molloy and the law is Buster Keaton-like in its potential for slapstick and destruction, but also attains the gravely serious and melancholy. Beckett’s writing is, first of all, remarkably balanced-throughout Molloy-between ironic quips and perceptive, affecting human observation so that a reader must continually weigh Molloy’s digression on toilet paper (the policeman has asked for Molloy’s “papers”), for example, with the vivid lines that immediately follow it: “We took the little side streets, quiet, sunlit, I springing along between my crutches, he pushing my bicycle, with the tips of his white-gloved fingers” (21). The writing effect here is to produce a kind of delirious but always lucid collage-patching together both startlingly beautiful and hilarious elements. Molloy and the policeman are obviously caught in the gagster and the straight-man roles, but they also suggest the father and son team.

The bicycle takes on a charming, limpid modesty as it literally runs along beneath the tips of the gloved-fingers of both the policeman and of Beckett’s prose. As the bicycle, and the journey itself, is stalled by the presence of authority, Molloy slips into an elegiac reverie concerning his profound loneliness: While still putting my best foot foremost I gave myself up to that golden moment, as if I had been someone else. It was the hour of rest, the forenoon’s toil ended, the afternoon’s to come. The wisest perhaps, lying in the squares or sitting on their doorsteps, were savouring its languid ending, forgetful of recent cares, indifferent to those at hand. Others on the contrary were using it to hatch their plans, their heads in their hands. Was there one among them to put himself in my place, to feel how removed I was then from him I seemed to be, and in that remove what strain, as of hawsers about to snap? It’s possible. Yes, I was straining towards those spurious deeps, their lying promise of gravity and peace, from all my old poisons I struggled towards them, safely bound. Under the blue sky, under the watchful gaze. Forgetful of my mother, set free from the act, merged in this alien hour, saying Respite, respite. (21-2).

Molloy’s exquisite meditation on rest and relief, framed by his acute sense of his separation from other human beings, serves to also grant the bicycle the dual purpose of practical machine and metaphysical prism. Janvier states that in Molloy “The body is powerless to continue, but it must continue: the bicycle is this impatience” (47). Molloy’s journey is obviously one of grim longing-his search for his mother is also a more general, sentimental quest for human connection and so his bicycle comes to embody the pathos of his loneliness. When Molloy leaves the police barracks with his bicycle, the quality of fading sunlight affects him once again and he notices the play of shadows on the wall: Let me cry out then, it’s said to be good for you. Yes, let me cry out, this time, then another time perhaps, then perhaps a last time. Cry out that the declining sun fell full on the white wall of the barracks. It was like being in China. A confused shadow was cast. It was I and my bicycle. I began to play, gesticulating, waving my hat, moving my bicycle to and fro before me, blowing the horn, watching the wall. They were watching me through the bars, I felt their eyes upon me. The policeman on guard at the door told me to go away. He needn’t have, I was calm again. (25)

It is fitting that Molloy’s encounter with the law resolves in this moment of play and official supervision. If Molloy is sentimentally searching for some kind of community or companionship, Beckett reveals that it perhaps can only take place-and finitely-in this other-, shadow-dimension. “A confused shadow was cast” articulates the oblique, ontological ambience of the entire Trilogy. Molloy, already excessively distanced from his own surroundings and his own being, now divides himself once more by throwing his lightless reflection against the wall. Molloy is indeed split but also re-unified here as well as the “I and my bicycle” become an “it.” For Molloy, the shadow play is obviously a semi-ecstatic event, as he concludes by grumbling that he “was calm again.” The shadow play also implies (“It was I and my bicycle”) how intimate Molloy is with his bike: the wall ostensibly integrates them both in a kind of ideal, wordless, Beckettian theatre until their independent forms are indistinguishable from each other.

But Molloy’s realism is precisely, if paradoxically, what makes his naivete so convincing. He tells the reader, “The shadow in the end is no better than the substance” (26). Molloy is an apparent amalgam of the hardened knowledge of cold experience and yet also the embodiment of radical optimism and innocence. Molloy follows his grim utterance above with a confession that if he ever thinks consciously about riding his bicycle then he invariably falls off. One of the joys of Beckett’s prose is that every line, so often pared down to its simplest, most honest form, yearns to be read allegorically. Molloy says, “I had forgotten where I was going. I stopped to think. It is difficult to think riding, for me. When I try and think riding I lose my balance and fall. I speak in the present tense, it is so easy to speak in the present tense, when speaking of the past. It is the mythological present, don’t mind it” (26). Molloy’s journey is obviously utterly complicated by memory and habit.

Importantly, Molloy’s speaking in the present tense is also-metaphorically-Beckett’s writing and so Molloy’s anxiety about the difficulty of “think[ing] riding” is also a potential pun on thinking writing. Of course, these lines are mobius strips of self-consciousness: Molloy and Beckett, like Duchamp’s Wheel, are caught in a circuit of hyper-self-awareness so that the journey (the riding and the writing) are apparently compromised by the first-, second-, third-order consciousnesses at play. However, Molloy is also caught in a temporal paradox in which “it is easy to speak in the present tense, when speaking of the past.” This tense is more specifically “the mythological present” which proves Molloy’s ability to make ironic even his own more sage insights. Part of the problem of time that Molloy explores, in its dark Proustian way, is exactly the dilemma of how a subject ever speaks the history of the self. To think too much, in Beckett, is to lose your balance and fall but also-conversely-to give rise to the most telling (moving) diversions. What Molloy calls his “raglimp stasis” (26) begins to look, and read, like whirlwind activity-and vice versa. Whatever “balance” Molloy locates is thus an avant-garde one. Just as the “mythological present” logically cancels out (makes impossible) the very temporal moment it inaugurates by laminating it with the past, so too does Molloy find that not only can he never fully stop or start but rather that he is always doing both simultaneously.

The hilarious pacing of Molloy itself confirms its investment in the blending of the sublime and banal. Shortly after Molloy rides out of town he surmises that “the most you can hope is to be a little less, in the end, the creature you were in the beginning, and the middle” (31). In the next sentence we read, “For I had hardly perfected my plan, in my head, when my bicycle ran over a dog.” The clause, “in my head,” is a strange and even apparently useless qualification which is made, however, immediate and humorous by Molloy’s bicycle then running over a dog. The stunning shift in focuses-from nebulous or abstract in my head to concrete my bicycle ran over a dog-fully situates Molloy as an endearingly powerless entity. For, it is his bike, for example, that appears to be the true perpetrator of the dog murder; and all of the aspects of Molloy’s environment are thus imbued with a vaguely if hilariously “human” quality. It is almost as if Molloy’s own consciousness, his ability to lose himself in making plans in his own head, is what reduces his own human presence. In separating himself from his surroundings (in becoming a virtual, thinking object), his bicycle is forced to stand-in for his physical agency.

click to enlarge

Figure 24

Laurel and Hardy in

Towed in a Hole,

Hal Roach-MGM, 1933.

Figure 25

Gustave Dore,

Don Quixote,

1862

All technologies are both time-machines and space-machines. Lorenzo C. Simpson, in his work Technology, Time, and the Conversations of Modernity, argues that technology “is a response to our finitude, to the realization that we are vulnerable and mortal and that our time is limited” (14). Technology, to some extent, is always anxious and always bodily. This suggests that technology works paradoxically to both counter-act the fact of mortality (to conceal or deny it) but to also function as an anxious, strangely emphatic symbol of our very finitude. It is revealing then that in the second part of Molloy (after Molloy’s reverse-travels have taken him back, so to speak, from where he and the reader started), Moran begins his narrative-not unlike Molloy-by making reference to his immediate surroundings and by then stating that “I shall be forgotten” (84). This line is followed by the mention that Moran’s “report will be long” and so both parts of Molloy quickly figure their protagonists as writers.

If, as Edith Kern argues, “His [Molloy’s] trials served but to lead him to his ‘mother’s room,’ where writing is identical with existence and existence means writing” then Moran’s being, too, is described in direct relation to his obligation to produce a written, literary report. It seems to me significant, also, that Moran, like Molloy, is immediately preoccupied with what vehicle (car, motorcycle, bicycle) to take on his journey. The preoccupation is unnecessary, of course, because Moran and his son soon end up-after much digression-leaving on foot. Indeed, Beckett’s genius “pacing” in these initial scenes of Part Two depend on his idiosyncratic fascination with the minutiae of walking and travel. For Beckett, the spectacle of Moran and Son trying to make progress, trying to proceed, is of course a decidedly complex and seemingly inexhaustible, philosophically rich, affair. Moran recalls, “Get behind me, I said, and keep behind me. This solution had its points, from several points of view. But was he capable of keeping behind me?” (118) Beckett’s discovery here is to hollow out infinite possibilities behind even the most rational and apparently complete utterance. Moran’s prosaic, even boring decision (from a traditional narrative sense) to keep Jacques behind him is not only contingent but also, finally, a source of powerful narrative humour and speculation. The problem and suspense of the journey or the quest, then, is construed-like a Laurel and Hardy film or Don Quixote (Figs. 24 and 25) itself-more around issues of the absurdity of mobility rather than those of conventional heroic trials. Moran himself declares-in lines that Beckett must be said to be at least partly present within, too-that, “I have no intention of relating the various adventures which befell us, me and my son, together and singly, before we came to the Molloy country. It would be tedious” (121).

What resolutely isn’t tedious, for either Beckett or Moran, is the description of bicycles. As Moran and his son wake up outside, and some vague distance from their objective, Moran prepares his son to travel to the next village in order to buy a bicycle. In the context of the Trilogy this is of course a decidedly fraught employment. First of all, the name of the destination-town is-rather unsubtly but still uproariously-Hole and so Jacques is being sent, metaphorically, into an abject absence: the anus. Moran and his son enjoy a long Moe and Curlyesque exchange about what type of bike, what price etc. until Moran accuses his son of stealing ten shillings. The two-page debate is finally resolved and Jacques heads off for Hole-yet before he is out of sight Moran yells one last request, instructing his son to buy a lamp for the bicycle. Beckett’s scenic architecture is comparable here to Molloy’s shadow-wall episode. He follows an extended passage of brilliant farce with a kind of lyrical, melancholy meditation that is always-necessarily-tinged with irony:

Later, when the bicycle had taken its place in my son’s life, in the round of his duties and his innocent games, then a lamp would be indispensable, to light his way in the night. And no doubt it was in anticipation of those happy days that I had thought of the lamp and cried out to my son to buy a good one, that later on his comings and goings should not be hemmed about with darkness and with dangers (133).

The bicycle is a form of elegiac transport, for Beckett, as much as a mechanical proof of the ridiculousness of the human subject. The power of the bicycle machine in Molloy is that it generates, or at least connotes, a sort of silence in the text. How does a reader finally process the weird union of intellectual slapstick and spiritual sadness? Beckett’s language always moves towards silence and death, but it does so with the utmost vocality and verve. To read the Trilogy is to some extent to encounter the sounds of speechlessness, the actions or mobilities of utter exhaustion.

So, as Moran’s lovingly described, imaginative bike lamp sends its glow out backwards over the text it is then compromised-thoroughly de-sentimentalized-by his apparent murder of a man. Moran, who has been waiting uneasily for his son’s return, is approached by a figure who seems to resemble himself and ostensibly kills this stranger by bashing him over the head. The murder scene (which is never explicitly narrated) enacts the very shadow-quality of the novel and also its fascination with identity and anonymity. Moran’s encounter is an encounter with himself and to some extent with his own speech and predicament. In this way Moran implicates the reader in the paradox of his terror: he has killed a man who eerily resembles himself and yet this victim is also radically anonymous-even disposable-in the context of the narrative. Moran’s predicament-who was the stranger? am I guilty?-is thus a mimicking of the reader’s interaction with an often brutally absurdist text. That is to say, Moran’s lostness in his own private narrative comes to ironize the reader’s own experience of deep bewilderment. In this sense then, Beckett’s writing is an explicit ethical challenge because he forces the question-especially in such a stripped-bare, cold, often human-indifferent landscape-how are emotional and physical violence supposed to be received?

When Moran’s son returns with a bicycle from Hole, the father & son team-like the single Molloy before them-become entangled with the machinery. The grim irony here is that the bicycle, like language itself, becomes exposed as merely a diversion-not as some evanescent, pure technology but rather as means to pass the time. All of Moran’s dialogue with his son about the bike is evidently and merely just something “to do”-rhetoric about the curious appetite for rhetoric. Moran and his son make it to Ballyba but it too is a finally unimportant destination. Molloy concludes, tellingly, in the shadow-world of both memory and writing. Molloy recalls his original mission-a voice asking him to complete his report-and then wonders if he is any freer now than before. The point seems radically incongruous, even ridiculously inflated, as the entire text has revealed not only these ideals as chimerical, but the technology and the language by which these ideals are fashioned as wholly contingent and constructed. Molloy ends, famously and literally, with an act of writing. Molloy says, “I went back into the house and wrote, It is midnight. The rain is beating on the windows. It was not midnight. It was not raining” (162). As readers, we are incorporated into this paradoxical final moment until it is unclear whether we are reading Molloy’s text or the narrative’s commentary on, and perhaps extension of, that very writing. That is to say, Molloy’s writing (a text unable to offer the real) suspends our act of reading Molloy-like him, perhaps, we are ultimately unsure of the boundaries and forces of our immediate material environment. Though, concluding in negation is also a strangely affirmative exit-a paradigmatic Beckettian mode-because it simultaneously invokes in the midst of its cancellations. Beckett’s phrasing here, on the minute level of grammar, enacts the text’s more general fascination with the commingling of subjects and mobility/death. The active, nearly suicidal desire, say, to end one’s life (to complete one’s report) is always apparently premised on a real dynamism and indisputable agency.

Duchamp/Beckett: Last Lap

click to enlarge

Figure 26

Marcel Duchamp,

To Have the Apprentice

in the Sun, in

Box of 1914

For the journey that is not a journey, Duchamp’s drawing-the sole drawing in his first publication of accompanying notes for the Large Glass entitled Box of 1914-To Have the Apprentice in the Sun is apposite as it illustrates a hard-pedalling bicyclist (the “apprentice”) proceeding on a diagonal line that runs up and across the staffs of music paper. The line or hill begins with a small loop underneath the rider and then ends at the right margin. The apprentice is an angelic rider-even a personification of musical perfection, a true note-en route to a kind of ethereal territory in which roads or lines or hills are unnecessary. The apprentice, in his scene of ascension, recalls the medieval church iconography in which cherubim and seraphim are shown riding on (mar)celifere-like winged-machines. Alternatively, the apprentice can be seen here as literally riding towards his own fall or even, quite simply and plainly, not going anywhere at all.

There is a Dedalusian aspect to the rider, too-the title To Have the Apprentice in the Sun (Fig. 26) pointing less at an ideal future location and more at a perverse desire to see the unfortunate apprentice actually in the sun. In a 1949 letter to Jean Suquet, Duchamp referred to the Box of 1914 drawing as a “silhouette” (283). This comment curiously situates the rider in the context of profiles, a kind of one-dimensionality, but then also in the context of shadows-a context of multi-dimensionalities. With his head bent, and body taut with pedalling, the apprentice is unbearably stalled-the bike itself seems full of motion and yet utterly frozen. Like Beckett, Duchamp employs the everyday technology of the bike to both embody and then complicate the “obviousness” of mobility. Marjorie Perloff stresses that this image epitomizes Duchamp’s fascination with concept of “delay.” Duchamp described “delay” as “merely a way of succeeding in no longer thinking that the thing in question [The Large Glass] is a picture” (Green Box). As Perloff writes, “To ‘have’ this particular ‘apprentice’ in the sun, as the title suggests, is thus not to ‘have’ him at all” (Stanford 7.1 1999).

Like so much in Duchamp’s corpus, the rider is also enacting an allegory of desire-in this instance, possibly one of delayed sexual consummation. The climax of the apprentice’s ride of desire, an apparently self-pleasuring kind of ride, is always maddeningly suspended. Onanism, again, is one of the more prominent themes of Duchamp’s Large Glass (Fig. 27). The Apprentice may be linked here with the wheels of the “Chocolate Grinder” (Fig. 28) (“the bachelor,” Duchamp informs us, “grinds his chocolate himself”) as well as the erotic “Water Mill.” (Fig. 29) Furthermore, in the Green Box, Duchamp explicitly links To Have the Apprentice in the Sun with the “slopes” and “illuminating glass” of the Large Glass. Duchamp’s mobile and slopes drawing in the Green Box is showing perhaps the ultimate conclusion of the Apprentice’s line-which is, in fact, a fall into the illuminating gas. We are involved here in what Duchamp calls, perhaps echoing Jarry’s Faustrollian theories, his “playful physics.” The illusion of motion is directly contingent on these planes of possibility and angles of action in delay. Like Beckett’s writing-poised for (in)action and yet always documenting the speech of speechlessness (imagination dead imagine)-Duchamp’s aesthetic is an impossible machine of almost-desire.

click to enlarge

Figure 30

Vibeke Tandberg,

Princess Goes To Bed

With A Mountain Bike, 2001

The reader or viewer of the avant-garde is necessarily involved in a game of identity and complicated progress: the how now/who now of Beckett is often complemented by the what is/when will of Duchamp. In such a subverted art experience, there is necessarily a demand for a new mode of reading and looking. Both Beckett and Duchamp use the technologies of the everyday to confuse its own modes: they effect this by using the habit of modern machinery against itself in order to finally break the pattern (or reveal the workings) of daily experience. In this way, reading and viewing are comparable to riding a bicycle or vacuuming or answering the telephone: everyday reflexes that are merely trained responses to a particular modern environment. The notion of recycling (despite the bad pun) is therefore vitally important here. What Duchamp calls in the Green Box the “junk of life” is thus inverted to read the life of junk: we see into the historicity of the modern object and thus into one component of the circuitry of the modern subject.

Aesthetic beauty for Beckett and Duchamp is less the victory of aesthetic form over mechanised and hackneyed contemporaneity, but rather the revelation of form (form as engineering) within modernity. So Duchamp’s delay, or Beckett’s deliberately counter-Joycean literature of failure, are both eagerly implicated in the inauguration of a grand scientific and artistic tension. In the Duchampian delay, as in the Beckettian grand exhaustion, the act of signification is aligned with the process of subject formation: the workings of modernity and history are exposed as vital, necessary elements in all forms of representation and technology. (There is nothing that does not form being!) So the bicycle, as an emblem of the manufacturing-, engineering-, marketing-genius of modernity is parsed-so to speak-until its powerful, informing tropics of chaos, pain, impossibility are laid bare.