click to enlarge

Figure 1

Antonio

Sant’Elia, La Città Nuova, Italy, 1914 Figure 2

Figure 2

Shiro Kuramata,

Glass Chair, 1976

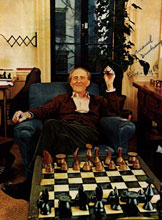

Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) was a French painter turned conceptual artist, film maker, erotic guru, and chess player. He was, however, never an architect, nor specifically interested in architecture, and yet, he has exerted a tremendous influence over a generation of architects practicing after 1975, as well as over current architectural historians and theorists. Contemporary literature in architectural theory has gone so far as to argue that architectural works created before many of the works of Duchamp, such as La Città Nuova (Fig.1), be understood within the context of Duchamp’s works.Architects have, in roughly the past twenty-five years, picked up on concepts in which Duchamp was interested and integrated them into their works. This has been possible largely because of dramatic shifts in the way that art is defined in this new postmodern era.Sundry Duchampian concepts or fascinations, such as projection, chance, and metaphor, seen throughout the wide range of his post 1912 works, have been interpreted and used by numerous architects and designers. This phenomenon has occurred both in a sort of direct homage to one or more of Duchamp’s works as well as in a more subtle, intellectual sort of homage, incorporating a Duchampian concept, such as chance, not only into a single architectural work, but into the way that an architect creates any architectural work.Some work, such as that of furniture designer Shiro Kuramata (Fig. 2), has been preoccupied with the former. Some architects claiming to be Duchamp’s standard-bearers, such as California team Morphosis, acknowledge Duchamp’s influence in both ways.Even famous and influential contemporary architects Frank Gehry and Robert Venturi also occasionally directly base a work on a work by Duchamp. However, the works of Gehry and Venturi are particularly useful in illustrating the latter, intellectual type of acknowledgment of Duchamp, as permeating all of their works are evidence of Duchampian thinking about concepts such as chance and metaphor.A final architectural firm, Diller + Scofidio, has incorporated so many Duchampian concepts, not only projection, chance, and eroticism as metaphor, but also ideas such as the infra-thin, ambivalence, ambiguity, and ephemerality, that their work can be seen as truly Duchampian architecture. This discussion seeks to establish why and how Marcel Duchamp has been so influential in contemporary architecture by thoroughly exploring the Duchampian concepts of projection, chance, and metaphor both within Duchamp’s work and that of contemporary architects whom he has influenced, and then further exploring these and other Duchampian ideas through the work of two postmodern architects upon whom Duchamp has been extraordinarily influential, Elizabeth Diller and Ric Scofidio.

click to enlarge

Figure 3

Marcel Duchamp, Given:

1. The Waterfall / 2.The

Illuminating Gas,

1946-1966, Philadelphia Museum of Art

Figure 4

Image of Antonio

Sant’Elia, 1914

At first it may seem somewhat strange, that Marcel Duchamp should be so influential on the theory and practice of architecture and design of the period after 1975, considering that Duchamp was not an architect. The only works that could be termed ‘architectural’ for which he was responsible, the door and room of Étant Donnés (Fig. 3) and the door that is neither open nor closed, would hardly elevate Duchamp to the status of a guru in contemporary architecture on their own. Duchamp did receive training in technical drawing, which including drawing mechanical and architectural objects, such as doors(1) but this, too, fails to qualify Duchamp as an architect. This problem is complicated even more by the fact that there were practicing architects in his milieu with interests similar to those of Duchamp. One such architect was Antonio Sant’Elia (Fig. 4), the Italian Futurist architect best remembered for his drawings for La Città Nuova. Sant’Elia, like Duchamp and many others living in the 1910s, was interested in non-Euclidean geometry, and the Futurists, like Duchamp, were affected by the new technological innovations of their day, such as the discovery of x-rays and the appearance of the incandescent lamp, the hydraulic generator, the skyscraper, cinema, and the automobile.(2)Duchamp was very familiar with the ideas of the futurists(3), and both men were similarly a product of their cultural milieu. Furthermore, unlike Duchamp, Sant’Elia actually created detailed urban plans and architectural drawings for a city of the future, La Città Nuova, integrating into an urban spatial form the new ideas about a space-time continuum.(4)

click to enlarge

Figure 5

Marcel

Duchamp, The Bride Stripped

Bare by Her Bachelors, Even

[a.k.a. The Large Glass], 1915-23

Figure 6

Marcel Duchmp,Cover of

The Bride Stripped Bare

by Her Bachelors Even [a.k.a.

The Green Box], 1934 (regular edition)

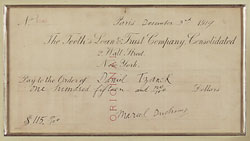

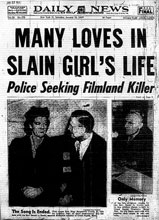

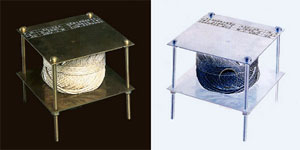

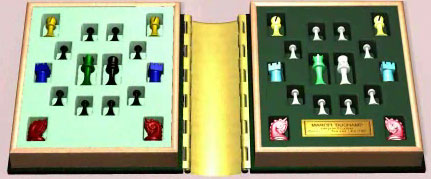

If Sant’Elia was infinitely more involved in architecture than Duchamp, and sharing many of the ideas Duchamp held in the 1910s, it is perhaps astonishing, then, that a current scholar of La Città Nuova, Sanford Kwinter, believes that La Città Nuova should be viewed within a Duchampian context.Kwinter argued in 1986 that, “La Città Nuova may be understood in this light less as a literal, realizable program than as a set of instructions [as Duchamp’s procedural Green Box], governing not only the assembly of isolated modules of (bachelor) machinery…”(5) Antonio Sant’Elia was killed in 1916 and the bulk of his work on La Città Nuova is from 1914,(6)while Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (Fig. 5), hereafter referred to as the Large Glass, referenced by the phrase ‘bachelor machinery,’ dates from 1915-1923. The Green Box (Fig. 6), an explanation of the Large Glass, dates to 1934.(7) In claiming that La Città Nuova be viewed within the context of works by another artist, not even an architect, which were created after La Città Nuova, Kwinter, besides pulling Sant’Elia’s work totally out of context, demonstrates the passionate love affair of contemporary architectural historians and theorists with Marcel Duchamp. The question remains, though, why is Duchamp so influential within contemporary architectural theory, while other seemingly valid figures, such as Sant’Elia, while still important, are much less cited than Duchamp?The simple answer is that the nature of Duchamp’s influence has nothing to do with architecture directly, and everything to do with his ideas. Duchamp did not specifically write, or at least did not intend to write, architectural theory, yet, it is in the realm of theory that he has been most influential, chiefly because he was the first truly idea-oriented artist, the antecedent of the conceptual artist.

Throughout his life, Duchamp was fascinated by chance. The Three Standard Stoppages (Fig. 7) are chance forms of measurement. The appearance of the Three Standard Stoppages, their lengths and shapes, were determined entirely by chance. His Monte Carlo Bond (Fig. 8) was created so that others might invest in a gambling trip that he wished to take. Would others take a chance and invest so that Duchamp could play a game of chance?There was also a strong element of chance in the creation of the readymades. The objects chosen as readymades were chosen at random, mass-produced, and were aesthetically indifferent, that is one would not usually go up to the object and feel anything about its aesthetic qualities one way or the other because it had none in its normal context. Fountain (Fig. 9), a urinal not markedly different from any other urinal, bought by Duchamp in an everyday New York plumbing shop, has been elevated to cult artistic status and was branded by some as an abomination and hailed by others as a beautiful form. Any other urinal would have served the artistic function just as well as the one that became Fountain, just as any other mass-produced urinal would serve a man who needed to relieve himself just as well. Each readymade involved an element of chance in this way.

Figure 7

Duchamp, Three Standard

Stoppages, 1913-14Marcel

Figure 8

Duchamp, Monte

Carlo Bond, 1924 Marcel

Figure 9

Duchamp, Fountain,

1917/1964

click to enlarge

Figure 10

Frank O. Gehry, Guggenheim

Museum in Bilbao (in two views),

Spain,1997

Figure 11

Le Corbusier, Villa Savoye,

1928-30

Figure 12

Morphosis, Diamond Ranch

High School, Pomona,

California, 2000

Figure 13

Marcel Duchamp,

bôite-en-valise, 1935-41

In an explanation of how the design for his Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao (Fig. 10), Spain, came about, Frank Gehry noted that it just happened, was a lot like a chance fluke.(8) This is in stark contrast to the Modernists of the early-middle twentieth century, who were obsessed by perfect proportions and the golden mean. Le Corbusier, for example, used a precise geometric formula in his early high International Style work of the 1920s (Fig. 11). He had rules controlling how line and form could be used and tried to adhere to a difficult system of proportion called the golden section. This required room proportion ratios to be 1:1.618.(9)

Gehry observed this in a statement concerning the freedom that chance gives an architect,

“I used to be a symmetrical freak and a grid freak. I used to follow grids and then Istarted to think and I realized that those were chains that Frank Lloyd Wright was chained to the 30-60 grid, and there was no freedom in it for him, and that grids are an obsession, a crutch. You don’t need that if you can create spaces and forms and shapes. That’s what artists do, and they don’t have grids or crutches, they just do it.”(10)

While International Style and earlier architects rigorously adhered to meticulous formulas, an architect today chooses the forms of a building, of a space, in the same way that Marcel Duchamp walked into a store and chose a readymade. They just do it. Much contemporary architecture, then, from the works of Frank Gehry to Robert Venturi to Peter Eisenman can be read as Architectural readymades.

Besides living legends such as Venturi and Gehry, younger, up and coming architects, are also interested in Duchampian ideas, specifically in the Architectural readymade. Thom Mayne, a younger California architect with an interest in the work of Frank Gehry and who practices under the name Morphosis, claims Duchamp as his idol. Morphosis tries to make every building an Architectural readymade. He claims that he, “treats materials, sanitary fittings, and bits of plan with innocent astonishment, that is, as objets trouvés.”(11) It can be said, then, that Morphosis selects its urinals along with the rest of the building components as Duchamp did. A recent Morphosis project, though, the Diamond Ranch High School in Diamond Bar, California, (Fig. 12), shows that Morphosis has made use of chance, of the Architectural readymade, in much the same way as Gehry.(12) For the school, Mayne created jutting, or projecting, forms, brought together at random, or at least to give that effect.

Eroticism as a metaphor was a constant motif throughout Duchamp’s career. Sometimes this was simply playful, such as issuing his bôite-en-valise (Fig. 13), portable museums, in an edition of the sexually significant number 69. Most often, these works were not specifically about eroticism, they just used eroticism as a metaphor for something else, namely art. Duchamp’s masterpieces, the Large Glass and Étant Donnés, first and foremost raise issues about the nature of artistic practice in light of technological, societal, and artistic change. The Large Glass was about the act of painting in an age in which abstraction challenged the mimetic nature of the craft, the fallacy of one-point perspective in relation to actual sight was well known, and photography and cinema could produce mimetic works more quickly, accurately, and cheaply than painting. This is shrouded in an elaborate game in which nine bachelors try to satisfy their desire and impregnate the ‘bride.’ Étant Donnés, on the previous page, was created in a time in which there was a crisis, a near-death incident, in the life of representational art. His hyper-realistic painted landscape in the background of the work and the complete illusionary nature of the work as a whole challenged the assumption of the middle of the twentieth century that painting, or art in general, should be abstract. This was in the guise of a nude woman with her sex exposed in the foreground. Duchamp not only used eroticism as metaphor, but used his own works as metaphors of each other. The Large Glass and Étant Donnés are both metaphors of each other not only because they are reverse projections of each other, but also because they allude to each other through having the same theme, the bride, the waterfall, and the illuminating gas.Architects have been, since the 1970s and ‘80s, using metaphor in a downright Duchampian manner, to explore what it means to be an architect in the face of the information technology revolution, computers replacing the t-square and drafting table, the ‘cult of the box’ of architecture of the middle twentieth century, the impact of the automobile and the highway on architecture and urbanism, and the increasing prevalence of mass architecture, such as strip malls. The issues raised by much current architecture because of and in response to these technological and societal shifts, is the same raised by Duchamp in works such as the Large Glass and Étant Donnés.

click to enlarge

Figure 14

Golden Goose. Downtown

Las Vegas (Fremont Street) by night

Figure 15

Mies van der Rohe,

Chapel, Illinois

Institute of Technology,

Chicago, 1953

Robert Venturi’s Learning from Las Vegas (1977) , a seminal work in postmodern architectural theory, uses metaphor, though definitely not of an erotic nature, to explain the state of architecture in America in the 1970s. Las Vegas is used as a metaphor for the need for increased decoration and less of the International style high seriousness of Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe (Figs. 14 and 15). Like Duchamp, who also rejected the high seriousness prevalent in artistic circles in his own time, Venturi used humor throughout the work. After the metaphor of Las Vegas itself, the book’s most overriding metaphor is that of the duck and the decorated shed. The duck, a building shaped like a duck, is a metaphor for buildings which are symbols. This is based on a real duck-shaped building, a restaurant specializing in roast duck, from God’s Own Junkyard.(13) A decorated shed, on the other hand, refers to any of the various average looking buildings by the highway which are heavily decorated with signs and logos, and more globally to any building covered with ornament. Within this framework, Chartres Cathedral is a duck (though it is a decorated shed as well), while Renaissance buildings are all decorated sheds.(14) (Figs. 16 and 17) Sentences from Learning from Las Vegas, such as “Minimegastructures are mostly ducks,”(15) show just how heavily Venturi relied upon metaphor. Really, Venturi’s duck and decorated shed are Duchamp’s bride in this respect.

Figure 16

Chartres

Cathedral, Paris,

1194-1260, architect unknown

Figure 17

Bernardo

Rossellino, Palazzo Piccolomini façade, Pienza, Tuscan, Italy,

ca. 1462

click to enlarge

Figure 18

Marcel Duchamp, L.H.O.O.Q., 1919

In Learning from Las Vegas, Venturi also suggested placing a replica of the shape and text of a marquee from Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas advertising popular comedian Flip Wilson to perform in the ‘Circus Maximus’ over a print by Piranesi of the Pantheon.(16) This gesture is the equivalent of Duchamp’s iconoclastic gesture in his painting L.H.O.O.Q.(Elle a chaud au cul.), or ‘she has a hot ass’, on a print of the Mona Lisa (Fig. 18). This work by Venturi, advertising Flip Wilson on the front of the Pantheon, is both a direct homage to a single work of Duchamp, L.H.O.O.Q., as well as a more intellectual homage to Duchamp through the use of metaphor.With Duchamp, the metaphor is again eroticism, with Venturi, it is Las Vegas. This work is also important in that it is so clearly directly indebted to Duchamp, one may surmise that Learning from Las Vegas, arguably one of the most important works in architectural theory of the late twentieth century, perhaps an important work in the whole history of architectural theory, would not have been written, or at least not have been written in nearly the same way, were it not for Marcel Duchamp.Marcel Duchamp’s ideas have been so important in contemporary architectural theory and practice that many architects and designers have created works which are inspired by literal or stylistic elements of Duchamp’s works. This is directly in contrast with Duchamp’s views on avoiding repetition and on the irrelevance of style or the visual, and is certainly not that most reverential way to pay tribute to the father of conceptual art. Works such as the readymades went against the ‘mimetic’ or ‘retinal’ nature of art, yet as Tilman Kuchler argued in a discussion of the ‘end of modernity and the beginning of play’, theysolicit processes or artistic representation and reproduction in the postmodern era.(17)This goes beyond reproducing Duchamp’s work, such as the inaccurate assertion hand-crafted reproductions of Fountain made to sell in Arturo Schwarz’s gallery. This type of homage involves miming the visual aspects of one of Duchamp’s works.Shiro Kuramata, a prominent Japanese furniture designer of the 1980s, frequently used this sort playful retinal homage to Duchamp in his work. Kuramata, like many postmodern artists, architects, and designers, called Duchamp his idol.(18) Works such as his Miss Blanche armchair of 1988 ( Fig. 19), left, playfully allude to Duchamp’s works, while ignoring much of the intellectual content of Duchamp. The chair’s title is actually a reference to Blanche Dubois of Tennessee William’s A Streetcar Named Desire, but Kuramata admitted that the embedding of paper roses within the acrylic body of the chair is a homage to Duchamp’s female alter ego, Rrose Sélavy.(19) A detail of Miss Blanche also elicits a visual, or retinal, comparison with a detail of the Large Glass. The visual effects achieved by the roses and by the nine malic molds are quite similar, though the thinking behind them could not be more different. Kuramata also created a set of acrylic perfume bottles, inspired by Rrose Sélavy’s perfume bottle, Belle Haleine, eau de voilette (Figs. 20 and 21). These works by Kuramata take their inspiration from Duchamp in a very literal way, and are therefore not Duchampian at all. This honorific literalization of Duchamp’s works has not, however, been the sole way in which Duchamp has appeared as an influence in current visual production. Rather, some have tried to copy or acknowledge Duchamp’s ‘style’ or ‘look,’ if such a quality even exists, because the larger and more important theoretical implications of Duchamp have made him such a popular figure, a veritable guru, in the contemporary era.

Figure 19

Shiro Kuramata, Miss

Blanche, 1988, Collection

SFMOMA, Photograph by Ben Blackwell

Figure 20

Shiro Kuramata, Perfume

bottle, 1991

Figure 21

Marcel Duchamp, Belle

Halein: eau de voilette

[Beautiful Breath: Veil Water], 1921

click to enlarge

Figure 22

Morphosis,Kate Mantilini

Restaurant, Beverly Hill,

California, 1986

Figure 23

Marcel Duchamp, Chocolate

Grinder No. 1, 1913

In the past, Morphosis, too, sometimes dabbled in a more literal and, therefore, less successful use of Duchamp. For Kate’s, a Hollywood restaurant completed by Morphosis in 1987 (Fig. 22), the architects made the centerpiece of the interior space a large mural of boxers and a chocolate grinder.(1)(At this time, Michael Rotondi, another young California architect, was also a principal of Morphosis. Rotondi and Mayne were partners until 1991.) This is meant to recall Duchamp’s amusing painting of a Chocolate Grinder (1911) (Fig. 23), amusing because it takes its inspiration from the French saying “Bachelor grinds his own chocolate [masturbates].” In the same article about Morphosis, “Duchamp Goes West”, Rowan Moore goes on to note that instances such as this are part of the reason that subtlety and originality are all too often lacking in current architectural practice.(21) Duchamp, Moore argues, mentioned too frequently or lightly, will become as meaningful as a Campbell’s Soup can, a Leon Krier pediment, or a Gehry fish.”(22)

Even Frank Gehry has, on occasion, been mildly guilty of this mimetic crime. The look of Gehry’s Telluride Residence in Telluride, Colorado, which has been in the planning stages since 1995, is based, in Gehry’s words, on Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase. (Figs. 24 and 25)(23) The house will step down the hill for which it is intended, just as Duchamp’s Nude steps down the stairs. Unlike Kuramata, however, who used roses to recall Rrose Sélavy, Gehry’s house does not go so far as to have an abstracted, monochromatic nude figure painted on it. Instead, the Telluride Residence is the mechanomorphic nude. The house serves as a metaphor for Nude Descending a Staircase, as well as a simple visual recollection of the painting, and thus escapes the mimesis of Kuramata.

Figure 24

Frank O. Gehry, Telluride Residence,

Telluride, Colorado 1996 ~,

Photo by Joshua White,

courtesy of Frank O.

Gehry & Associates

Figure 25

Marcel Duchamp, Nude Descending

a Staircase No. 2, 1912

Many contemporary architects, not only Gehry, have been visually inspired by Nude Descending a Staircase. For example, the fire station designed by Zaha Hadid for the Vitra complex in Germany (1990-1993) (Fig. 26), was also inspired in part by Duchamp’s Nude,(24) and the aerial computer plan of Morphosis’ Diamond Ranch High School can also visually be likened to Nude Descending a Staircase. There is even debate over whether Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao looks more like Nude Descending a Staircase or like Futurist artist Umberto Boccioni’s sculpture, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space. (Fig. 27)(25) Again, these comparisons and debates lead away from the true nature of Duchamp and the reasons for which he is so much discussed and quoted. It is perhaps partly coincidental that contemporary deconstructivist architecture looks so much like Nude Descending a Staircase, partly that the deconstructivists are visually stimulated by works of Boccioni and of early Duchamp, and partly due to the fact that, as mentioned previously, Duchamp’s cult status encourages many writers as well as architects to invoke Duchamp and identify with him. When one realizes that works such as Antonio Sant’Elia’s preliminary drawings for La Città Nuova also have much visually in common with structures such as Diamond Ranch High School, the explanation of Duchamp’s stylistic influence through cult association becomes the most convincing.

Figure 26

Zaha Hadid, Vitra Fire Station, Weil am Rhein, Germany, 1994(whole , left; part, right)

Figure 27

Umberto Boccioni,Unique

Forms of Continuity in Space,

1913, Collection Museum of Modern Art,

Acquired through the Lillie P. Bliss Bequest

click to enlarge

Figure 28

Liz Diller and Ric Scofidio,

Blur Building by day

and night, Yverdorn-les-Bains,

Expo 2002, Switzerland

Figure 29

Marcel Duchamp,Manual

of Instructions

for the Assembly of “Etant

donnés”: “Approximation démontable,

exécutée entre 1946 et

1966 à New York”, 1966,

Collection of Philadelphia

Museum of Art

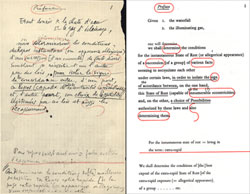

For the architectural firm of Diller + Scofidio, sex and eroticism, as well as other Duchampian fascinations, are important themes in their work. Architects Liz Diller and Ric Scofidio achieved much fame in 2001 for their pavilion for the Swiss Exposition of 2002), the Blur building, a ‘building’ made almost entirely of water vapor, with a little steel used (Fig. 28).(26) In 2002, Diller + Scofidio published their notes (four years worth) for the project in a book called Blur: The Making of Nothing. The book contains reproductions of the notes in all their forms, on cocktail napkins, on lined yellow notebook paper, and with photographs of the rings of binders and colors of folders, much in the same way that Duchamp’s manual for the Étant Donnés were published by the Philadelphia Museum of Art (Fig. 29). Numerous other parallels with Duchamp can be seen in the work of Diller + Scofidio. This architectural work shares the ephemeral quality of the readymades. Just as many of the original readymades were thrown away when their exhibition was over, this building literally faded away, evaporated when the exposition was over.This pavilion can be read as the ultimate expression of another Duchampian concept, the infra-thin. Dawn Ades described the infra-thin as follows,

“An example of ‘visible infra-thin’ is iridescent cloth, or shot silk, which has a different character or colour according to the -light…Infra-thin then points to a condition of liminality, that is, something on the threshold (between inside and outside, for example); the interface between two types of thing (smoke and mouth); a gap or shift that is virtually imperceptible but absolute…Infra-thin encompasses time and space as well…”(27)

Like iridescent cloth, a pavilion made of water vapor can be seen through, its appearance changing with light and weather conditions.Indeed, in the making of the pavilion, many photographs were taken with time, relative humidity, and temperature noted.(28) Such a building would hover within the threshold between inside and outside, its bounds being imperceptible and ever-changing, its duration ephemeral. The walls of such a building would be walls and not walls (again, the door is neither open nor closed), ever shifting, and either barely visible or oppressively opaque depending on the amount and type of light filtering through the vapor. Ben Rubin, a project manager for Diller + Scofidio, called the cloud building “pure visual noise.”(29) This is undoubtedly what Duchamp meant by the infra-thin, noise which could be seen but not heard, a building made of water vapor, a building that was there and not there. Just as an advertisement for Flip Wilson could never have been placed on a print of the Pantheon had it not been for Marcel Duchamp’s L.H.O.O.Q., neither could a structure made of water vapor have been ‘erected’ without the antecedent of Duchamp’s infra-thin.

This infra-thin building straddled the line between the material and the immaterial, between reality and fantasy, and between conceptual art and architecture. Marcel Duchamp explored new media in his own work, such as the use of mass-produced, purchased objects as his readymades. Similarly, Diller + Scofidio explored a new architectural medium, water vapor, in this highly innovative structure. As with Duchamp, the work was meant to be experienced. Just as one can not fully appreciate Étant Donnés without going to the Philadelphia Museum of Art where it is installed and looking through the peepholes, the experience of the water vapor pavilion lay in the experience. By only reading about it or looking at photographs of it, one loses the experience of getting wet and of losing one’s way in a cloud. Another part of the experience of the water vapor pavilion was the ambiguity and anonymity into which visitors were submerged as they moved through the space. Each visitor was given an identical raincoat, a costume which reinforced the participatory nature of the spectacle (as well as being very useful for remaining somewhat dry). Looking forward to the work, Liz Diller commented on the blur effect,

“We use vision to assess identity; a quick glimpse of another person allows us to identify his/her gender, age, race, and social class. Normally, this visual framework precedes any social interaction. Within the cloud, however, such rapid visual identification is not possible. The foggy atmosphere, combined with visitors in identical raincoats, produces a condition of anonymity. It will be difficult to distinguish a 25-year old Japanese fashion model from a 13-year old Indian boy from a 70-year old Russian grandmother.”(30)

Diller + Scofidio seek to put architecture at the service of the mind just as Duchamp sought to put art at the service of the mind. The pavilion was not designed to be aesthetically pleasing through its lines or forms. It had no lines and its forms were ever shifting. Rather, the work was designed to make people think about the meaning of architecture and the interface of technology, humans, and the natural environment. Whether a person was even willing to consider the pavilion ‘architecture’ or not was not at issue. Diller + Scofidio gave the viewer, the participant the same experience that Duchamp gave viewers of Fountain when it was exhibited in 1917. The experience, the fun in viewing these works was the chance to think about them afterward and decide whether or not they really were art or architecture.

click to enlarge

Figure 30

Marcel

Duchamp, Comb, 1916/1964

Figure 31

Marcel Duchamp,

Rendez-vous du Dimanche

6 Février 1916, 1916

In the works of both Duchamp and Diller + Scofidio, performance art plays an important element.(31)Duchamp created one of the readymades, the dog comb (Fig. 30), in front of his patron’s Walter and Louise Arensberg. He had created a textual message on four postcards sent two weeks prior to the event, inviting the Arensbergs to this rendez-vous (Fig. 31). This event can be seen as the precursor of the happening of the 1960s, just as attendance at the Diller + Scofidio pavilion can be seen as the latest generation of the happening. In their book, Diller + Scofidio included numerous pictures of themselves working with their crew to create the ‘Estructur.’ They drew crowds and media attention, and this was an integral part of the conception of the work.(32)Finally, eroticism was a very important part of both the pavilion, the Blur building, and the entire Swiss Expo.02. There were four sites for Expo.02, Neuchatel, Murten, Biel, and Yverdon.(33) Yverdon, the site of the pavilion, was themed “Sexuality and Sensuality,”(34) and Diller + Scofidio and their team, “to avoid contentions of individual authorship, the group members would merge identities to become ‘Extasia’, or ecstasy, in anticipation of winning the preferred site of Yverdon [Diller + Scofidio favored the theme of sexuality and sensuality above the other themes].”(35) (Though Diller + Scofidio did produce Blur at the Yverdon site, Extasia was eventually disbanded.)(36)As the building was to be created on the Yverdon site, themed sexuality and sensuality, the building was expected to take on the Yverdon characteristics.

The organizers of the exposition created detailed explanations of what each of the four themes was all about by comparing each of the four’s responses and attitudes, much like a personality quiz in a popular magazine.

For Yverdon, some of these were:

“Code words: sensuality, sexualityAntonym of code words: asceticismKey questions: Can sensuality and transcendence, eroticism and

sexual drive coexist?Architecture: round, amoeba-like, soft, bubbly, knobby, smallForms: round, organic, soft, amorphous, flowing, carnal, curved,

bumpyDuration: moments, phasesSymbols and cult figures: Romeo & Juliet, Cupid, Aphrodite,

CasanovaActivity: kissing, letting goSeason: summerA phrase: you kiss wellPhilosophical model: hedonism, passion, self-surrenderWhat’s going on, baby?: gender debate, imposedIndividuality: intimacyDrug: aphrodisiacs, alcoholForms of communication: whispering, pillow talk, shoutingTones/noises: lip-smacking, Bossanova, heartbeat, panting, jukeboxObjects: electric plug, dam, a lonely lost ski, vibratorDeath: heart failure, death at orgasmDrink: Bloody Mary, water”(37)

So, the initial task faced by Diller + Scofidio was to create an innovative temporary exposition pavilion recalling the many qualities listed above. Diller + Scofidio chose the site because of their interest in eroticism, and are showing a Duchampian influence in this way as well. These architectural constraints owe, however, to the phenomenon of postmodernism. In 1910 or 1950, for example, no government organization would have asked an architect for a building which recalled lip-smacking and a lonely lost ski. Though the actual pavilion itself was probably not the least bit erotic, it achieved a certain eroticism by using verbal means, the list on the previous page, to make people think about sex when they think about the Blur building. This is much the same tactic which Duchamp used in the Large Glass. His notes for the Large Glass explain the complicated process of desire and visualize undressing of the bride which is inherent in the work, though not visually detectable without the notes to instruct the viewer. A large mass of water vapor in Switzerland may be very erotic, just as Duchamp’s completely non-representational rendering of a bride may be; it is all dependent upon the framework of ideas within which the viewer approaches the work, and has nothing to do with the visual. The eroticism of Diller + Scofidio can be traced both to an interest in Marcel Duchamp and to the rule breaking of the culture of today. In a final analysis, though, the mere idea of a building, which is not a building, made of water vapor, and devoted to thinking about sex (as opposed to sex itself) detached from any visual or retinal mode of artistic expression, is decidedly Duchampian.

Marcel Duchamp has been quoted and acknowledged time and time again by contemporary architects and theorists because of particularly Duchampian ideas, such as eroticism as metaphor, his uses of new media, and his desire to move away from the retinal qualities of art towards an art which was at the service of the mind. Some writers and architects, including Sanford Kwinter, Shiro Kuramata, and Morphosis have at times misused Duchamp because his name is so en vogue. This has occurred by either invoking Duchamp’s name when no connection really exists or by paying a literal, retinal homage to one or more of Duchamp’s works. Many others, though, have incorporated Duchampian ideas into their own works in a more intellectually based homage. The Deconstructivists are indebted to his ideas about projection and chance, and Robert Venturi (Fig. 32) could not have made his playful jabs at the high seriousness of International Style architecture without Duchamp. Finally, the firm of Diller + Scofidio created a building which can be read as a truly Duchampian building, an embodiment of the infra-thin, playful performance and experiential art, and of a highly intellectualized eroticism. Though Duchamp was never an architect, his thinking has made possible deformed forms, has allowed Flip Wilson’s act to enter into the once sanctified realm of high art, and has allowed architects to literally erect buildings of clouds.

Figure 32

Robert Venturi, Fire Station No. 4,

Columbus, Indiana, 1967 (left);

Vanna Venturi House, Chestnut Hill, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania,

1962 (middle); Trubek and Wislocki Houses, Nantucket Island,

Massachusetts, 1972 (right)

Notes

1. Pierre Cabanne, Duchamp & Co (Paris: Terrail, 1997) 32.

1. Pierre Cabanne, Duchamp & Co (Paris: Terrail, 1997) 32.

2. K. Michael Hays, ed., Architecture Theory since 1968 (Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press, 1998) 586.

2. K. Michael Hays, ed., Architecture Theory since 1968 (Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press, 1998) 586.

4. Sanford Kwinter, “La Città Nuova: Modernity and Continuity,” Architecture Theory since 1968, ed. K. Michael.Hays (Cambridge, Mass: The

4. Sanford Kwinter, “La Città Nuova: Modernity and Continuity,” Architecture Theory since 1968, ed. K. Michael.Hays (Cambridge, Mass: The

MIT Press, 1998) 608.

5. Amy Dempsey, Art in the Modern Era ( New York:Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2002) 91.

5. Amy Dempsey, Art in the Modern Era ( New York:Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2002) 91.

7. Gehry Partners, Gehry Talks: Architecture + Process (New

7. Gehry Partners, Gehry Talks: Architecture + Process (New

York: St. Martin’s Press, 2002) 140.

8. John Pile, A History of Interior Design ( New York: John

8. John Pile, A History of Interior Design ( New York: John

Wiley & Sons, Inc:, 2000) 278.

9. Gehry Partners, op. cit. 140.

9. Gehry Partners, op. cit. 140.

10. Rowan Moore, “Duchamp Goes West,” Blueprint 36 (May 1987):20.

10. Rowan Moore, “Duchamp Goes West,” Blueprint 36 (May 1987):20.

11. Alice Kimm, “Morphosis Diamond in the Rough,” Architecture Week4 (June 2000): 11.

11. Alice Kimm, “Morphosis Diamond in the Rough,” Architecture Week4 (June 2000): 11.

12. Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown, Learning from Las Vegas

12. Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown, Learning from Las Vegas

(Cambridge, Mass.:The MIT Press, 1977) 88.

17. Tilman Kuchler,Postmodern Gaming: Heidegger, Duchamp, Derrida(New York: Peter Lang, 1994)121.

17. Tilman Kuchler,Postmodern Gaming: Heidegger, Duchamp, Derrida(New York: Peter Lang, 1994)121.

18. David Hanks and Anne Hoy, Design for Living: Furniture and Lighting,1950-2000 (Paris: Flammarion, 2000)186.

18. David Hanks and Anne Hoy, Design for Living: Furniture and Lighting,1950-2000 (Paris: Flammarion, 2000)186.

23. Gehry Partners, op. cit. 183.

23. Gehry Partners, op. cit. 183.

26. Diller + Scofidio Firm, Blur: The Making of Nothing (New

26. Diller + Scofidio Firm, Blur: The Making of Nothing (New

York: HenryN. Abrams, Inc., 2002) 1.

27. Cox Ades, and Hopkins, op .cit. 183.

27. Cox Ades, and Hopkins, op .cit. 183.

28. Diller + Scofidio Firm, op. cit. 70-1.

28. Diller + Scofidio Firm, op. cit. 70-1.

31. Cox Ades, and Hopkins, op. cit. 208.

31. Cox Ades, and Hopkins, op. cit. 208.

32. Diller + Scofidio Firm, op. cit .285.

32. Diller + Scofidio Firm, op. cit .285.

Bibliography

Adcock, Craig. “Duchamp’s Eroticism:

A Mathematical Analysis.” Marcel Duchamp: Artist of the Century.

Ed. Rudolph E. Kuenzli and Francis M. Naumann. Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press, 1996.___.“Marcel Duchamp’s Approach to New York: ‘Find an Inscription for the Woolworth Building as a Ready-made’.”

Dada/Surrealism. Vol. 14 (1985): 52-65.

Ades, Dawn, Neil Cox, and David Hopkins.

Marcel Duchamp. London: Thames & Hudson, 1999.

Baird, George. “La Dimension Amoureuse

in Architecture.” Architecture Theory since 1968. Ed. K.

Michael Hays. Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press, 1998.

Banham, Reyner. Theory and Design

in the First Machine Age. New York: Praeger, 1960.

Cabanne, Pierre. Duchamp & Co.

Paris: Terrail, 1997.

Colomina, Beatriz. “L’Esprit Nouveau

between Avant-Garde and Modernity: The Status of Artwork and the

Everyday Object.” Architecture Theorysince 1968. Ed. K. Michael

Hays. Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press, 1998.

Dempsey, Amy. Art in the Modern

Era. New York:Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2002.

de Solà-Morales, Ignasi. Differences:

Topographies of Contemporary Architecture. Cambridge, Mass:

The MIT Press, 1997.

de Vries, Hilary. “What’s Doing in

Los Angeles.” New York Times 28 Sep. 2003, section 5: 14.

Diller + Scofidio Firm. Blur: The

Making of Nothing.New York: Henry N.Abrams, Inc., 2002.

Duchamp, Marcel, Iconoclast.“A Complete

Reversal of Art Opinions.” (reprinted from Arts & Decoration,

Sept. 1915)In Studio International (Jan./Feb. 1975): 29.

Gehry Partners. Gehry Talks: Architecture

+ Process. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2002.

Giedion, Sigfried. Space, Time and

Architecture. Cambridge Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1949.

Girst, Thomas. “(Ab)Using

Marcel Duchamp: The Concept of the readymade in Post-War and Contemporary

American Art.” Tout-Fait: The Marcel Duchamp Studies Online

Journal 2. 5 (April 2003): Articles.

Hanks, David and Anne Hoy. Design

for Living: Furniture and Lighting, 1950-2000. Paris: Flammarion,

2000.

Hays, K. Michael., ed. Architecture

Theory since 1968. Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press, 1998.

Henderson, Linda Dalrymple. The

Fourth Dimension and Non-Euclidean Geometry in Modern Art. Princeton,

N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1983.

_ _ _.”X-Ray and the Quest for

Invisible Reality in the Art ofKupka, Duchamp and the Cubists.”

Art Journal (Winter 1988): 323-40.

Kuchler, Tilman. Postmodern Gaming:

Heidegger, Duchamp, Derrida. New York: Peter Lang, 1994.

Kuenzli, Rudolph E. and Francis M.

Naumann, eds. Marcel Duchamp: Artist of the Century. Cambridge,

Mass: The MIT Press, 1996.

Kwinter, Sanford. Architectures

of Time: Toward a Theory of the Event in Modernist Culture. Cambridge,

Mass.: MIT Press, 2001.

Kwinter, Sanford. “La Città Nuova:

Modernity and Continuity.” Architecture Theory since 1968.

Ed. Hays, K. Michael. Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press, 1998.

Maxwell, Robert. Sweet Disorder

and the Carefully Careless. New York: Princeton Architectural

Press, 1993.

Moore, Rowan. “Duchamp Goes West.”

Blueprint 36 (May 1987): 18-20.

Pasadena Art Museum. Marcel Duchamp.

Exhibition catalog, 1963.

Pile, John. A History of Interior

Design. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc:, 2000.

Powers, Edward D. “Fasten

your Seatbelts as we Prepare for our Nude Descending.” Tout-Fait:

The Marcel Duchamp Studies Online Journal2.5 (April 2003): Articles.

Puglisi, Luigi Prestinenza. Hyper

Architecture: Spaces in the Electronic Age. Basel, Switzerland:

Birkhauser, 1999.

Reichenbach, Hans. The Philosophy

of Space and Time. New York: Dover, 1958.

Venturi, Robert and Scott Brown, Denise.Learning from Las Vegas. Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press,1977.

Wood, Beatrice. “Marcel.” Marcel

Duchamp: Artist of the Century. Eds. Kuenzli, Rudolph E. and

Francis M. Naumann. Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press, 1996.

Figs. 3, 5-9, 13, 18, 21, 23, 25, 29-31© 2005 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris. All rights

reserved.