Duchamp planned each detail of this complex work, and left a huge corpus of notes, sketches, and blueprints, documenting not only his intentions and the desired final outcome, but also the different executive techniques for each single part of the Glass. These notes were published by Duchamp himself in three main collections.

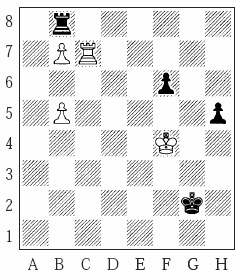

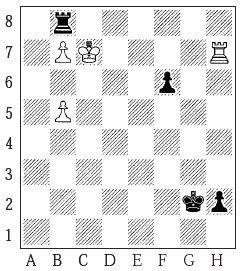

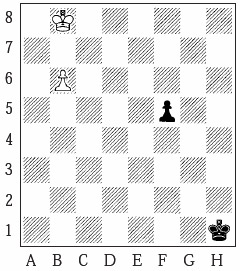

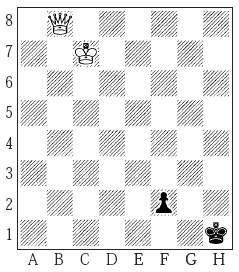

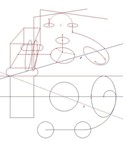

Figure 4

Marcel Duchamp, Bride’s Domain, in the

Large Glass(detail), 1915-23

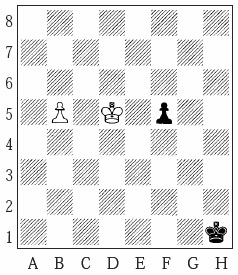

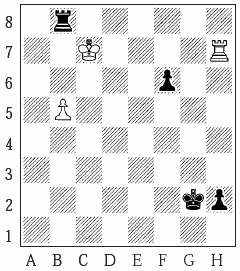

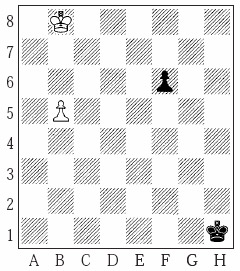

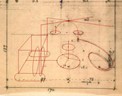

Figure 5

Marcel Duchamp,Bachelors Apparatus, in the

Large Glass (detail), 1915-23

Two main parts constitute the Glass: the higher and the lower ones. The higher part is the realm of the Bride, (Fig. 4) and according to Duchamp’s intention, it depicts the 2D

projection of a 3D shadow of a 4D Bride. Thus, the realm of the Bride is intended to be a true 4D realm, which however cannot really be seen, since it is as depicted on a 2D support (the sheet of glass). The lower part is the realm of the Bachelors (Fig. 5) or the Bachelor apparatus (or utensil). In contrast with the Bride’s realm, the Bachelor’s realm is a 3D world. Thus it is imperfect in comparison with the 4D higher realm. In a note belonging to the White Box (but already issued with some minor variants in the Green Box), Duchamp wrote:

Principal forms, imperfect and freed

The principal forms of the bachelor apparatus or

utensil are imperfect:

Rectangle, circle, square, parallelepiped, symmetrical handle; demisphere.-i.e. these forms are mensurated (interrelation of their actual dimensions and relation of these dimensions to the destination of the forms in the bachelor utensil.)

In the Bride – the principal forms will be more or less large or small, no longer have mensurability in relation to their destination: a sphere in the Bride will have any radius (the radius given to represent it is “fictitious and dotted.”)

Likewise, or better still, in the Pendu Femelle parabolas, hyperbolas (or volumes deriving from them) will lose all connotation of men-surated position.

Thus, the two parts of the Glass represent two distinct realities. The lower realm is imperfect and only tries to emulate the higher dimensionality of the Bride’s realm by means of expedients and tricks (very effective, as we shall see).

These tricks are largely based on perspective representations and on elementary geometric transformations. These transformations will gradually become more and more general, and, as we pass through the threshold of the horizon (the area which divides the two parts of the Glass) from the lower half into the 4D realm of the Bride (following the pathway described by Duchamp), we finally reach a world where, abandoning any metrical trait of the objects, only more general geometrical transformations take place: the topological ones. The subject is already thoroughly discussed by scholars .

Perspective is not only the drawing system used by Duchamp to compose the lower part of the work, but also (and better) perspective in itself is one of the most important themes of the Glass. Indeed, we have quite explicit statements by Duchamp, such as the following,

given during a famous interview with Pierre Cabanne, that supports this contention:

Duchamp: […] In addition, perspective was very important. The “Large Glass” constitutes a rehabilitation of perspective, which had then been completely ignored and disparaged. For me, perspective became absolutely scientific.

Cabanne: It was no longer realistic perspective.

Duchamp: No. It’s a mathematical, scientific perspective.

Cabanne: Was it based on calculations?

Duchamp: Yes, and on dimensions. These were the important elements. […]

Scholars largely speculated (and still speculate) on the meaning of such a rehabilitated perspective, no longer having a realistic purpose, being instead a mathematical and

scientific procedure.

Duchamp’s authoritative biographer Calvin Tomkins wrote for instance:

Vanishing-point perspective, which gave the illusion of three dimensions on a two dimensional surface, had been abandoned by modern artists who wanted their art to be a real thing rather than an imitation of reality. Why, then, did Duchamp, who certainly shared that ambition, choose to master such a discredited device? Was he looking for a mathematical formula through which he could actually evoke the presence of a fourth dimension? Whatever serious ambition he may have had along these lines he abandoned soon enough.

Rhonda Roland Shearer suggests that Duchamp could have used a complex technique based on the overlapping of several different perspectives at once. According to her, such

a technique could explain both some strange features in the historical photos of the readymade and the difficulties one encounters as he or she tries to recreate the perspective of the lower half of the Glass, starting from its original blueprint (plan and elevation). She says for instance:

Most Duchamp scholars have either accepted or praised Duchamp’s perspective skills. The problem remains, however, that I and a few other scholars have actually made 3-D models from Duchamp’s plans

— and none of us can find any one perspective projection view that matches Duchamp’s perspective drawings! Moreover, the process of trying to recreate the Large Glass perspective drawing from what a viewer would see of the 3-D model via perspective (equivalent to what one eye or camera lens sees) quickly becomes maddening. When you fit one part of the Large Glass model to its projection in Duchamp’s perspective drawing (say; part A, the ellipse in one wheel of the Chocolate Grinder, for example — see illustration 49A), the rest (parts B through Z) immediately fall out of place. We lose the fit of part A, and all the other parts C through Z, once part B is matched — etc.

A few lines above, we also read:

My discovery that the strangely distorted Chocolate Grinder uses the same systematic characteristic approach also found in the hatrack, coatrack and urinal (and a large set of other examples not discussed in this essay) returns us to Duchamp’s words that I used at the beginning of this essay — a quotation that now bears repeating.

Shearer shows a complete map of “at least” 43 different viewpoints which could have been used by Duchamp for the perspective of the Glass. Unfortunately, Shearer’s article is mainly focused on Duchamp’s readymades. The procedure used to inspect the Glass’s perspective is only briefly described, and only supported by means of 3D animations.

In the present paper, I will describe with some details the procedures I used to check the perspective of the Bachelor apparatus and will present and briefly discuss the outcomes reached.

In addition, considering some serendipitous discoveries I made by moving the elements of the Bachelor, as a further thesis, I would like to point out that the internal motions of the Bachelor apparatus (carefully planned and described in the Notes by Duchamp himself)

could be considered ways that permit the Bachelors to emulate the higher dimensionality of the Bride.

1.2. General procedures and remarks

Cabrì Géomètre II is the software I

used to reconstruct the perspective of the Glass. It is a world wide known pedagogical software, commonly used to teach geometry in high schools, thus it is not specifically oriented to graphic applications or to professional 3D rendering, but instead it is aimed at building geometric objects (even very complex) which can be dynamically transformed according to well defined geometric constructions and rules.

The basic objects that Cabri furnishes are the basic geometric elements of Euclidean geometry, as usually taught at school, such as points, straight lines, segments, angles, polygons, conics, and so on.

Cabri works essentially on the plane, but following the rules of projective geometry, it makes it possible to represent 3D objects in perspective (or even higher dimensional objects, such as a hypercube, for instance).

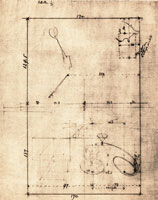

Just such a feature interested me, as I intended to verify Duchamp’s statement about his mathematical, scientific use of perspective. Indeed my concern was to reconstruct the correct perspective of the Glass, starting from the detailed and precise metric information we read in the autograph sketches of the elevation and plan of the Bachelor apparatus (Duchamp carefully gave us even the exact position of the vanishing point).

As a second step, I intended to compare the aseptic geometric drawings obtained with Cabri, with the reproductions of the actual Glass and of its parts. To do that, I used a second tool developed for using Cabri in Internet-like environments: CabriJava.

This program allowed me to superimpose Cabri figures on the corresponding reproductions by Duchamp and to adjust them in a continuous way until the figures and the reproductions matched (or did not).

Here is the key question: Which kind of adjustment is allowed in order to state that Duchamp’s perspective matches the mathematical construction?

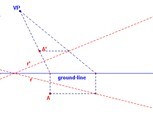

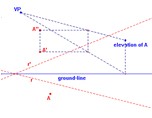

To answer that question, let us consider the perspective construction of a simple parallelepiped. Once we have the metric values for both the plan and the elevation of the parallelepiped (refer to Applet 1)and once we choose the vanishing point VP and the ground line (i.e. the elements given by Duchamp with the sketches of the plan and the elevation of the Bachelor apparatus), a degree of freedom still remains: following the standard perspective rules, we have to choose a couple of corresponding straight lines r and r’, for example the diagonal AC and the corresponding diagonal A’C’ .

Applet

1 depicts the situation. You can drag the straight line r’ to modify the figure, but always obtaining a perspective consistent with the given data, i.e., the metric of the parallelepiped, its position in the space, and the position of the vanishing point and the ground-line.

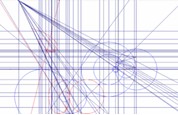

Perspective constructions and adaptations of Duchamp’s originals have been made for the overall view of the Bachelor apparatus and for each of its main elements. We shall discuss them later with some details.Fig. 6 shows how Duchamp’s elevation and plan sketches were inserted in Cabri..

Fig. 7 and Fig. 8 illustrate the two basic steps followed to construct the perspective rendering of an A point in the plan sketch, passing through the A’ image of A on the ground-plane, and then elevating it at the A’’ position, according to the position of A in

the elevation sketch.

click to enlarge

Figure 6

Duchamp’s elevation and plan sketches

inserted in Cabri

Figure 7

Two basic steps illustrating the construction of the perspective rendering

of a single point, given its position in plan and elevation sketches

Figure 8

2.1. The overall view

Let us start with the perspective of the overall view.

To make pictures more suitable for the internet (therefore with not too heavy files) the elements of the Bachelor apparatus are inserted schematically, just to check the correctness of their mutual positions according to the rules of perspective. The corresponding details for each inserted element are checked in separate figures.

click to enlarge

Figure 9

Marcel Duchamp, The Bride stripped

bare by her Bachelors, Even, 1913

Figure 10

The straight line r’

The overall perspective is compared with both the Glass and the preparatory sketch of 1913 named The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even, like the Glass itself. We shall refer to it simply as the 1913 Sketch (Fig. 9).For the lower part of the actual Glass, see below Applet 2 and Applet 3). This double superimposition is necessary because the important element called the Toboggan, one of the most difficult pieces to render in perspective, is actually absent in the Glass (remember that it was left unfinished by Duchamp) while it is present in the 1913 Sketch.

In both Applet 2 and Applet 3, CabriJava has some problems in displaying the ellipses of the Water Mill, which indeed are incomplete, and in addition an unexpected straight line is drawn starting from them. The same problems still remain for some curves of the Toboggan. However, despite these problems, I think that Applet 2 and Applet

3 will help understand the overall perspective.

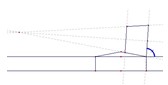

Why? Look at the straight line r’ in Fig. 10

r’ is the perspective correspondent of the straight line r in the plan, which passes through the bottom-left point of the so called Chariot (the parallelepiped containing the Water Mill) and through the centre of the circle representing the Chassis of the Chocolate Grinder. The choice of line r’ is free, but according to that choice we obtain different perspectives. Thus, by dragging the blue line in Applet 2 and Applet 3, you will see how the perspective could change accordingly, always remaining consistent with Duchamp’s data .

Anyway, the problems of the applets are definitely overcome with Fig. 11 and Fig. 12 (which are static), where the geometrical perspective of Cabri is correctly displayed on the background of Duchamp’s originals.

click to enlarge

Figure 11

The geometrical perspective of

Cabri correctly displayed on

top of Duchamp’s original

1913 sketch and the lower half of the Large Glass

Figure 12

The geometrical perspective

of Cabri correctly displayed

on top of Duchamp’s original

1913 sketch and the lower half of the Large Glass

Look at Fig. 11. The major discrepancies between 1913 Sketch and the Cabri figure are on

the right side of the picture:

one of the blades of the Scissor (the lower on the right) doesn’t match perfectly with its counterpart;

The right Sieve (the Sieves are the conical shapes just under the Scissor) is slightly in a lower position relative to the Cabri figure;

the Toboggan (the spiralling line on the right) is slightly shifted down.

In contrast, the left part of the 1913 Sketch matches quite well the remaining elements of the Cabri figure particularly the ellipses of the Chocolate Grinder. The left Sieve also matches perfectly the one in the Cabri figure.

In my opinion, some trivial explanations can be considered for the mismatches: maybe the reproduction of the 1913 Sketch used here is slightly rotated in the clockwise sense, around a centre located somewhere near the centre of the Chariot; this could explain why the

most evident discrepancies are on the right half of the picture, whereas the better matching is on the left. A second explanation could be that the sheet used by Duchamp for the 1913 Sketch could be somehow deformed. Indeed the squaring of the drawing (as I saw in all the photos I could examine, including the one used here) is not perfect.

Consider now the singular shape of the Toboggan. It is a strange mix of semicircles and semiellipses disposed on oblique planes: its correspondence with the Cabri figure, even though imperfect, is quite shocking; remember, indeed, that Duchamp drew it by hand;

it means that the drawing was made point per point. The exact placement of even just one of those points (starting from its position in plan and elevation) can be considered a very difficult task for anyone having only an intuitive knowledge of projective geometry.

click to enlarge

Figure 13

Possible construction lines of the Toboggan

To have the right idea of such difficulties look at Fig. 13 which displays the construction lines necessary for just one point for each of the four arcs forming the Toboggan (thus multiply these construction lines al least 4-5 times).

Consider now Applet 3 and the corresponding static Fig. 12, which superimposes the Cabri

figure on the lower part of the actual Glass.

Look at Fig. 12. The reproduction of the Bachelor apparatus matches quite well the Cabri

figure: look especially at the Scissor and the Sieve on the right, which fit a lot better with Cabri figure than the ones of 1913 Sketch. Also, the ellipses circumscribing the Water Mill seem to match it perfectly.

Consider finally the supports of the Chariot named the Runners with their four semicircular shapes. They scarcely match the Cabri figure. Note however that the Runners were not

yet present in the sketches of plan and elevation, thus we have no measures for them. I simply used four semi-circumferences without making any attempt to recreate the correct image.

In conclusion, the inspection of the overall perspective seems to suggest that the reciprocal positions of the main elements of the Glass are consistent with the hypothesis that Duchamp correctly used the rules of perspective. It is worth noting in particular his skill in managing very complex constructions such as the one for the Toboggan, especially considering that he was self-trained in perspective.

2.2. The Chariot with the Water Mill, the Capillary Tubes and the Cemetery of Uniforms and Liveries

The simplest solid to render with perspective is the parallelepiped with edges parallel and perpendicular to the horizon: it is the case of the Chariot. Not equally trivial is to draw the wheels of the Water Mill contained in the Chariot. Nonetheless the perspective rendering of this elements is almost perfect.

Applet 4 shows how the geometric construction fits the corresponding detail of the Glass. Because of some possible problems with CabriJava in displaying objects, we shall refer to Fig. 14, which is static, but displays the picture correctly.Here is a problem: the overall framework of the Chariot is made by rods which actually have thickness and width, whilst in Duchamp’s preparatory sketches of plan and elevation they are considered as pure linear elements without thickness and width. This implies a quite arbitrary superimposition of Cabri figure on the Glass picture (unless one considers a number of different possible assumptions regarding the passage from the sketches to the actual Glass, which I didn’t).

Apart from this problem, the perspective created with Cabri matches quite well the parallelepiped of the Chariot.

Observe now the wheels of the Water Mill.

click to enlarge

Figure 14

Static image

showing how the

geometric

construction fits

the

corresponding detail of the Glass

First, let us consider the ellipses circumscribing the Water Mill (in red in Fig. 14): they touch exactly the peripheral points of each paddle (as we already noticed in the overall perspective of the Bachelor apparatus), except for the paddle in the foreground. But there is no error here: indeed, Duchamp preferred to clip the parts of the paddles which fall beyond the limits of theChariot.

Look now at the ellipses (in blue) touching the internal points of each paddle. Duchamp didn’t insert them in the sketches of plan and elevation. Therefore, we don’t know the actual radius of such circles. Just for this reason, I inserted in Applet 4 the red large point. As the user drags it vertically, the radius of the internal Water Mill wheels varies accordingly. The match with the Glass is satisfactory.

Consider now the eight spokes of the Water Mill wheels. I drew them under the assumption that they formed a regular octagon, and placing two of them along a vertical line. They also perfectly match the originals.

Some minor mismatching are there with the paddles of the Water Mill, but they are not severe, in any case.

Let us finally consider the perspective of the nodes of the so called Capillary Tubes, from which the 9 Malic Moulds hang, forming the so called Cemetery of Uniforms and Liveries.

In the sketches of the elevation and plan, the positions of the 9 numbered nodes are present, but, unfortunately, some measures are missing, namely those necessary in the plan sketch. Therefore I deduced them by measuring and scaling the distances directly on the sketch. The outcome displayed in Applet 5 is quite unsatisfactory. In particular, the nodes (and accordingly the Uniforms) nos. 2, 3, and 7 are clearly misplaced, whereas the remaining ones are only approximately right. Even by dragging the red diagonal (which modifies the perspective viewpoint), the drawing remains wrong (at least with respect to the preparatory sketches).

In conclusion: the perspective of the Water Mill shows some minor mismatches with the Cabrifigure; namely: some paddles seem to be not properly drawn. For the rest, the geometric construction easily fits the corresponding parts of the Glass.

In contrast, the nodes of the Capillary Tubes are misplaced. We must consider however, that the sketches are quite reticent regarding this detail, and we cannot rule out the possibility that the Capillary Tubes were more carefully planned before the execution of the actual perspective of the Glass.

2.3. The Chocolate Grinder

The Chocolate Grinder is often said to have the most problematic perspective. Indeed, it seems “strangely distorted” according to Shearer.In a second, stimulating essay, written in collaboration with Stephen Jay Gould, it is argued that:

Scholars have simply and uncritically accepted Duchamp’s claim that he rigorously used these principles in his major works. Ironically, however, no one who actually attempted the experiment has ever been able to render the bachelor machinery of the Large Glass under classical perspective, unless they alter Duchamp’s own drawings and therefore conclude that he was not, after all, a very accurate geometer. The Chocolate Grinder, especially, does not seem properly drawn, and no one has been able to show how the device might turn without the wheels interpenetrating and thus, to make the metaphor literal, grinding to a halt.

click to enlarge

Figure 15

Marcel Duchamp, Chocolate Grinder, No. 2 ,

1914

Figure 16

Marcel Duchamp, Chocolate Grinder, No. 1 ,

1913

Figure 17

Geometric features of the Chassis and the

Rollers

The second and definitive painting of the Grinder (namedChocolate Grinder, No. 2 (Fig. 15), dated 1914) is quite different relative to the first one (dated 1913) (Fig. 16), not only because it openly shows its second important identity (connected with electromagnetism and wireless telegraphy), discussed by Linda Henderson, but also because (as we shall see further on in this section) it acquires well-defined perspective construction, unlike the first version, whose perspective is quite problematic.

The first problem to solve in order to check the perspective of the Grinder, is to understand its geometry. Indeed, the sketches of plan and elevation are quite incomplete.

Essentially the Grinder is formed by three rollers (which seem to be frusta of a cone) placed on a Chassis (a cone with altitude much smaller than the radius of its base).

Duchamp’s sketches give us the complete measures necessary to reconstruct the Chassis, but for the roller, only two measures are given: the diameter of the circle of the major base and the length of the generatrix. No measures of angles are given. Reconstructing the rollers without additional assumptions is thus impossible.

At first I thought that the roller had to roll without sliding on the Chassis, and (of course) always rotating on theChassis itself, without leaving it. Geometrically speaking, this implies that the vertexes of the cones of each roller must coincide with the vertex of the cone of the Chassis; but looking at the actual Grinder we immediately understand that it is not the case: their vertexes clearly lay far beyond the vertex of the Chassis(Fig. 17). Thus the rollers grind the chocolate by sliding on the Chassis. Thus the assumption about the kind of friction of the rollers on the Chassis was wrong .

If we start from the measures of the roller given by Duchamp (radius of the major base and length of the generatrix), accepting their conical shape, and giving the angle the major base forms with a horizontal line, then the frustum of the cone is completely assigned (see Fig. 17).

In order to find the exact value for the measure of the unknown angle, I inserted in the Cabrifigure a corresponding further degree of freedom, allowing the user to drag the line corresponding to the major base of the roller in the elevation.

click to enlarge

Figure 18

Contact lines of the rollers with

the Chassis

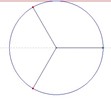

Duchamp’s sketch of the plan doesn’t contain information about the mutual positions of the rollers and the exact positions of the contact points of the rollers with the Chassis. Thus, further assumptions must be made. Fig. 18 shows the simplest assumption (plan view of theChassis): the axes of the rollers form 120° angles, and one of them is parallel to the ground-line of the perspective. This hypothesis will prove exact (except for minor mismatches indicated below).

Finally let us examine Applet 6, which superimposes Cabri figure of the Grinder onto the 1914 picture Chocolate Grinder (No.2). I used the 1914 picture instead of the actual Grinder of the Glass, because we know that the latter was obtained by simply transferring on glass the former; thus using the 1914 picture I avoided considering those mismatches possibly derived from the transfer on glass, maintaining instead the focus on possible true perspective mismatches.

The outcome is once again unexpected, because the matching is almost perfect.

Applet 6 allows the user to see that:

The two ellipses corresponding to the Chassis and to the Necktie match well the Cabri figure (the ellipses of the Chassis are slightly smaller than the corresponding ones in the Cabri figure). The blue point on the top of the Grinder axis (or Bayonet) over the Necktie also matches well the point where the handle of the Necktie intersects the axis of the Grinder.

So good is the matching of the fixed parts of the Grinder with the Cabri figure that we see even the same very small portion of the Chassis visible in its higher part between the rollers!

Let us consider now the rollers. The grey line in the elevation, running along the major base of the roller allows the user, by dragging it, to choose the better unknown angle we talked about above (my best estimate is 81,9°).

The vertexes of the equilateral triangle (in the little circle under the Grinder) indicate the positions of the rollers (namely their contacts with the Chassis). The green point can be dragged in order to rotate the roller, and to test its matching with the original picture for each of the three positions.

In two cases (the two rollers in the background), the matching is almost perfect, whereas the roller in the foreground shows a minor mismatch, because the ellipse corresponding to its major base is slightly larger than in the Cabri figure.

In particular, note the blue points that indicate the center of the bases of the frustum of the cone. In the case of the roller to the right, the blue point coincides exactly with the insertion point of the roller on its axis. In the case of the roller in the foreground, one of the blue points matches perfectly the center of the major base of the roller.

click to enlarge

Figure 19

Tentative position

of the Louis XV legs

as vertex of an

equilateral triangle

Figure 20

One only visible leg

under the

assumption of

Fig. 19

Let us now consider the Louis XV legs of the Chassis. At first I thought that, because of the equilibrium of the whole device, the three legs had to be placed at the vertices of an equilateral triangle. Accordingly, the vertex corresponding to the leg in foreground is such that the exact position of the equilateral triangle must be as in Fig. 19.

Look now again at Applet 6. The three grey vertical segments and the corresponding cyan extremities indicate the position of the legs of the Chassisin case the legs were planned to be positioned as in Fig. 19. The background legs are clearly misplaced, whatever was their planned shape. The only visible leg in the perspective drawing would be that in foreground, whereas the others would be covered by the Chassis, as in Fig. 20.

Fig. 20 shows the Grinder with one only leg: even though appropriate for both the equilibrium and the perspective, it makes the whole Grinder seem to be supported by one only leg, which, of course, would be impossible.

The addition of the background legs makes the drawing acceptable for the eyes, but wrong for perspective. Indeed, in order to make the perspective we see in Chocolate Grinder (No.2), the background legs wouldn’t be placed according to Fig. 19 (the only disposition ensuring the equilibrium of the device): they have to be slightly shifted forward, which however makes the equilibrium impossible.

So far we have faced something paradoxical: if you pay the tribute required by the retina, you will obtain a thing which cannot stand up (a quite Duchampian statement, we have to acknowledge). Here I emphasize the Duchampian key concept of instability. Interestingly, a similar kind of paradox between retinal and mental data, with similar conflict between equilibrium and instability concepts, has been already discussed in terms of the Bicycle Wheelby Shearer.

click to enlarge

Figure 21

A further investigation of the perspective project

in the 1913 Sketch

A further investigation of the sketches makes things clear. In both the 1913 Sketch and the elevation, we can see the legs actually drawn (see Fig. 21). In fact nothing tells us that they are disposed as an equilateral triangle; this misleading assumption was made because the visible legs are three, but very probably they actually are four, disposed as a square, like in Fig. 21. Indeed three of them are clearly visible in both of Duchamp’s sketches, whereas the fourth would-be leg (the posterior one) couldn’t be seen in neither of them: in the elevation because it is exactly behind that one in the foreground, and in 1913 Sketch because it is hidden by the Chassis. But this fourth leg is necessary for the equilibrium. According to this new assumption Duchamp’s perspective would turn out to be correct, and the equilibrium of the device would be safe. On the other hand, no actual datum contradicts this hypothesis of four legs, which in my opinion is thus confirmed. In conclusion: the perspective rendering of the legs is correct.

Consider now the threads sewn through canvas in the Chocolate Grinder, (No. 2) then carefully reproduced in the Glass.

Applet 7 shows the roller completed with similar threads, and helps check the correctness of their orientation. It proved to be consistent with the adopted perspective in two cases (the right and the foreground rollers) but also revealed some minor mismatching in the third case (the roller in background). In my opinion just the wrong perspective of the threads of the background roller makes the overall perspective of the Grinder difficult to be accepted for the eye.

To convince that what we said about the perspective of the Grinder No. 2 holds its validity in the passage to the Glass, look at Applet 8, which displays the Cabri figure superimposed on the actual Grinder of the Glass. Once again the matching is almost perfect.

Before concluding this section, I want to say a few words comparing the perspective rendering of both the first and the second version of the Grinder.

Applet 9 clearly shows that the perspective of the first Grinder is definitely wrong (at least accepting the measures of Duchamp’s sketches and the assumptions I declared above). The user can try to adapt the Cabri figure to the picture of the first Grinder, by dragging either the red diagonal or the green point (which have the same meaning as in Applet 6), but the outcome will be in any case unsatisfactory. Particularly the Necktie and the rollers seem to be totally wrong.Thus we can say that the passage from the first to the second version of the Grinder shows an extraordinary leap in Duchamp’s perspective skill.

In conclusion we can say that despite its strangely distorted view, and in spite of its intrinsic difficulty, the Grinder is one of the best executed elements in the perspective of the Glass. In any case the mismatches revealed above are consistent with the hypothesis that Duchamp drew the Glass according to the ordinary rules of perspective.

Recall Gould’s and Shearer’s statement that : «…no one has been able to show how the device might turn without the wheels interpenetrating…». Look now at Animation 1. It shows theGrinder in action. Definitely, the rollers do not interpenetrate as the device is grinding.

Please refresh the page, if the animation stops

Animation 1

2.4. The Sieves or Parasols

click to enlarge

Figure 22

The Yport sketch, 1914

The Sieves (or Parasols) are the conical shapes that are disposed in semicircle behind the Scissor.

Unlike other elements of the Glass, we have detailed sketches which describe not only the measurements and the position of the cones, but also the detailed perspective procedures followed by Duchamp. We can see such perspective sketches and projects in the Green Box. But the most important sketch, drawn at Yport during the summer of 1914, is not published in any of the cited collection of notes. We shall refer to it as the Yport sketch. (Fig. 22)

Particularly, we note the following shortcut Duchamp used to speed his work.

Once the drawing of the base-circle of the first cone was executed by interpolating 8 reference points (clearly visible in the sketch), Duchamp exploited the semi-circumferences where the corresponding points of the other cones lay, and divided them with the vertices of the inscribed dodecagons (which is a quite simple and speedy procedure). As I worked with Cabri, I used the same procedure.

click to enlarge

Figure 23

The actual geometry of the Sieves

The Yport sketch also clearly shows a further detail: the declared altitude of each single cone (we read twelve cm in the elevation sketch) was probably modified by Duchamp on the basis of the geometry displayed in Fig. 23, in turn based on Yport sketch.

The shared altitude CH of the cones is such that the perpendicular to the base AB of the first cone intersects the base of the second one exactly at point C (and similarly for the others as well). Thus, the involved angle being of amplitude 30°, and being OH=23 cm, the measure actually used for the Sieves is CH=13.28 cm.For construction of the Sieves, I followed the geometry of Fig. 23, instead of using the measurements given in the elevation sketch.

Look finally at Applet 10. It shows that, once the best inclination of the diagonal (the red one) is chosen, the matching is perfect.

2.5. Some conclusion about the perspective of the Glass: the static viewpoint

Duchamp composed the Glass by hand and, above all, used absolutely unconventional media, which required him to invent ex novo appropriate techniques of execution. In general, we must suppose that drawing on glass is not as easy as drawing on paper or on canvas, especially if one of the main goals was precision, as in the case of the Glass.Just to have a correct idea of what this could mean, read the following description, regarding the execution of a preparatory study for the Chariot:

His first idea was to etch the design on the glass with fluoridic acid, a powerful corrosive used by commercial glass workers. “I bought paraffin to keep the acid from attacking the glass except where I wanted,” he said, “and for two or three months I struggled with that, but I made such a mess, plus the danger of breathing those fumes, that I gave it up. It was really dangerous. But I kept the glass. Then came the idea of making the drawing with the lead wire – very fine lead wire that you can stretch to make a perfect straight line, and you put a drop of varnish on it and it holds. It was very malleable material, lovely to work with.” (Duchamp used fuse wire, a coil of which was a staple in Paris apartments then.) .

We also already reminded that Duchamp was substantially self trained in perspective. In a note of the White Box we read:

Perspective.

See Catalogue of Bibliotèque St. Geneviève

The whole section on Perspective :

Niceron, (Father Fr., S.J.)

Thaumaturgus opticus

The note suggests that while Duchamp was working at the library of Sainte Geneviève (1913-14) he read the whole section on perspective, and particularly (at least so we may assume from the note) the treatise on perspective and optics by mathematician Jean-François Niceron (1613-1646), titled Thaumaturgus opticus .

Thus, in the years Duchamp was composing the first elements of the Glass, he also was concluding his education in perspective.

We can obtain the exact measure of his progress in perspective skill in those years by comparing the two versions of the Grinder (dated 1913 and 1914), as we did in section 2.3.

On the other hand, regarding now my reconstruction of the perspective, remember that procedures and tools I used are quite non-professional:

– the used software is perfect to study and teach geometry, but in general not for 3D rendering;

– the reproduction used are photos whose reliability is not certified (think for instance about possible parallax errors or perspective deformations);

– the photos were in addition reduced or enlarged to match the scaled measures I used withCabri, and such adaptations could be imperfect…

These considerations surely reduce each pretension of precision, but at the same time they also reduce the relevance of the minor mismatches revealed above.

Let us finally reconsider the perspective elements of the Glass that we have examined, in order to answer to the question: is the perspective of the Glass canonical (and/or correct)? Are there elements which permit us to hypothesize a non-canonical (and/or incorrect) use of perspective?In my opinion, the only mismatch one can consider a true error, or possibly as a non-canonical use of perspective, is the one regarding the nodes of the Capillary Tubes. For the rest the execution of perspective is quite stunning, especially for some elements such as the Grinderand the Toboggan.I believe that the matching between the geometrically reconstructed perspective and the actual perspective of the Glass is in general good or even perfect in some cases.Let us then reconsider Shearer’s argument. She describes the minor mismatches between computer aided designs and Duchamp’s originals

When you fit one part of the Large Glass model to its projection in Duchamp’s perspective drawing (say; part A, the ellipse in one wheel of the Chocolate Grinder, for example — see illustration 49A), the rest (parts B through Z) immediately fall out of place. We lose the fit of part A, and all the other parts C through Z, once part B is matched — etc.

Her statements can be discussed at two different levels.

At the level of single parts of the Glass, such as the Grinder, the Chariot, and so on (the micro level), I think that her statement is substantially wrong. With the exceptions of the nodes of theCapillary Tubes, the mismatches revealed by the inspection above are completely acceptable and consistent with the hypothesis that the Glass was drawn according to the usual rules of perspective, and must be considered as absolutely minor imprecisions due to Duchamp’s free-hand execution. I believe this conclusion holds unless a unitary theory can be formulated that explains all the mismatches at once.

Shearer proposes a unitary theory of this kind about the perspective of the historical photos of the readymade, but there are no explanations about the way that theory could be extended to theGlass.

Let us pass now to the higher level (the macro level), that of the overall view. Some further preliminary considerations are needed.

I executed Cabri figures in different sessions by separating the principal elements of the Glass.

This procedure risks creating a trivial error: choosing different and mutually inconsistent diagonals (possible diagonals are, for instance, the straight lines r and r’ in Fig. 10) for different figures can generate mistakes (remember that Duchamp’s measures allows such a degree of freedom). This implies the possibility of an overall perspective inconsistency, even if each individual element was rendered in correct perspective. In other words, choosing inconsistent diagonals would be equivalent to choosing different viewpoints. (This possibility agrees to some extent with Shearer’s proposal concerning the presence of several, different viewpoints in the perspective of the Glass).

The same considerations I did for the computer aided reconstruction of the perspective, could be applied to the execution of the actual Glass by Duchamp: remember indeed that the elements of the Glass were added by him one by one (even because each piece had to be executed with an appropriate technique) through successive and separate steps, which could expose Duchamp himself to the same risk of error I was exposed to.

Thus, it was very important to verify the mutual consistence of the details. In the contrary case, it would have been an important evidence for applying Shearer’s theory of multiple viewpoints to the perspective of the Glass (but, in such a case, there would be no evidences for an intentional choice by Duchamp, and consequently we couldn’t rule out the possibility of a simple mistake).

Now, in order to verify the perspective consistence of the single details with the overall view there were two possible ways:

either choosing every time the same couple of diagonal lines (which sometimes was very inconvenient), or choosing different couples of corresponding line, but verifying that they were consistent to each other.

I chose the second way. The check for consistency was done by comparing in each figure the position of the same straight line, namely r’ (refer to Fig. 10).

The check returned a positive response: each diagonal r passing trough the left lower point of the Chariot and the centre of the Chassis in the plan, corresponds to a straight line r’ in the ground plane of perspective, forming the same angle (16.3°) with the ground line. Hence, the details are perspectively consistent with each other and with the overall view.

Definitively, Duchamp used the canonical perspective rules, and mastered them at the highest level.

What is then the meaning of his mathematical, scientific perspective?

Often people think of mathematics as something which deals essentially with numbers. If there are no numbers there is no mathematics.

Remember for instance that after Duchamp’s claim about the mathematical use of perspective, Cabanne asked: «Was it based on calculations?» (we shall consider Duchamp’s interesting reply below), or even recall what Tomkins told about a possible formula.

Now, geometry is mathematics, and I think that Duchamp meant (among other things) that he used thoroughly projective geometry. Try to execute the perspective of the Toboggan to understand how much projective geometry he used.

Let us return to Cabanne and Duchamp dialogue.

Cabanne: Was it based on calculations?

Duchamp: Yes, and on dimensions. These were the important elements.

A few lines below we also read:

I almost never put any calculations into the “Large Glass”

but again, a few lines below:

At the same time I was doing my calculations for the “Large Glass”

I think that Duchamp used here the word calculations in the more general meaning of mathematical (namely geometrical) operation, construction, deduction: the only true calculations actually necessary for the drawing were the proportions possibly necessary for scaling the measures and a few minor operations ; for the rest there are only geometrical constructions.

Here, I want to emphasize the second element of Duchamp’s answer: that of dimensions, which of course refers to the fourth dimension.

Remember the already-cited Tomkins’ statement:

Was he looking for a mathematical formula through which he could actually evoke the presence of a fourth dimension? Whatever serious ambition he may have had along these lines he abandoned soon enough.

In other words Tomkins says that, even admitting the attempt to find the mathematical key which could open the door of the fourth dimension, Duchamp soon abandoned it, possibly (I’m hypothesizing) in favor of speculation on non-Euclidean geometry. I don’t agree with Tomkins. Not to diminish the importance of non-Euclidean geometry, but to emphasize the importance of the concept of higher dimensions in relation to perspective.

So far, we regarded Duchamp’s perspective from an eminently static viewpoint, and (consequently, I say) no reference to higher dimensions were highlighted.

The main goal of the remaining part of this article is just to establish a connection between the perspective of the Bachelor apparatus and the emancipated spatiality of the Bride realm, by introducing a new important element: that of motion.

3.1. The Chariot in the fourth dimension

In the introduction I argued that the Bachelor apparatus emulates the higher dimensionality and the topological properties of the Bride realm by coupling perspective with motion.

click to enlarge

Figure 24

Marcel Duchamp, Glider

Containing a Water Mill (in

Neighboring Metals), 1913-15

Let us start our course along this strand with the demonstration of a subject already widely discussed by scholars, regarding the Chariot . In the years 1913-15 Duchamp worked at a preparatory study of the Chariot, named Glider Containing a Water Mill (in Neighboring Metals). (Fig. 24)It is the same element of the Glass, executed on a semicircular hinged panel of glass, which can rotate.

Applet 11 shows the situation. The red point on the bottom can be dragged to rotate about its hinge the plane where the Chariot is drawn. To simplify the drawing, the Water Mill is missing, to better focus the attention on the essential details.

The actual Chariot is drawn on a 2D support (the sheet of glass), and emulates its own status of 3D object by means of perspective. Accordingly, the 2D sheet of the glass emulates the ordinary 3D space. Hence the rotation of the Glider around its hinges suggests the rotation of a 3D object in a 4D hyperspace. Notice that just the sheet of glass used as support of the drawing allows to complete correctly the metaphoric turn in the fourth dimension: indeed just the transparency of the glass allows us to see the Chariot specularly reversed, as it reaches its final position. In fact we face an inverse congruence between two figures; just the exit from the 3D space and the rotation into the hyperspace allows two 3D figures inversely congruent to overlap on one another.

This idea is clearly presented by Duchamp in a note of the White Box and is widely discussed by Adcock .Returning now to the applet, we can see a strong optical effect (also known as the Necker cube inversion), which can be described as if the Chariot would turn inside out as if it were a glove. Just this effect can be considered as a mental turn into the fourth dimension.

We can understand the variety and the subtlety of the game that Duchamp plays here, by comparing the rotation of the Glider with many other rotations of planes, everywhere present in the Bachelor apparatus. Consider for instance the rotation of the plane which ideally sustains the first Sieve (which we can actually see in the Yport sketch). Applet 12 allows the user to see this rotation by dragging the red point. Here we face a plane which rotates in a 3D space, giving rise to cones (which are 3D shapes) directly congruent with the starting one; on the contrary the glass plane of the Glider, which is 2D but perspectively simulates a 3D space, rotates in a true 3D space which accordingly simulates a 4D hyperspace, and gives rise to a second Chariot, inversely congruent to the starting one.

Now we can understand why Duchamp chose just the reproduction of the Glider as the cover of the White Box: remember indeed that the notes of this collection are mainly focused on the fourth dimension and its properties.

In short, with the Glider Duchamp suggests a rotary motion which allows the observer to look at two different Chariots, the one being the specular reversed image of the other, with the involvement of the fourth dimension concept we presented above.

Now, consider that the same thing can actually be done with the whole Glass, by simply walking around it. Once again the transparency of the glass permits the observer to look at two different Bachelor apparatuses, specular one to another, with analogous involvement of the fourth dimension concept. The motion of the observer around the Glass corresponds to the rotary motion of the Glider about its hinge as the observer stands still.

We shall exploit similar relative exchanges in motion (observed object rotating about its hinge and fixed observer vs. fixed object and observer moving around it) especially with the Sieves(in section 3.3.) and we shall consider the notes which carefully describe this inversion.

3.2. A new possible identity of the Grinder

One of the most important innovations of the 1914 painting Chocolate Grinder (No.2) are the threads directly sewn on the canvas; they obviously recall the coil-winding of an electromagnet.

Consider now a new possibility. The threads could also be related to the geometric concept ofruled surface.

A ruled surface is one which can be obtained by a straight line moving in the ordinary 3D space and leaving wherever it passes its trail: the ruled surface.

A note of the Green box, usually considered as the only one of this collection directly related to the theme of the fourth dimension , also describes rotational motions of lines considered as generatrix; in addition the note contains ubiquitous suggestions of moving lines which leave a sort of trail forming surfaces; also, the note connects such a practice with the idea of circularity:

The right and the left are obtained by letting trail behind you a tinge of persistence in the situation. […]

And on the other hand: the vertical axis considered separately turning on itself, a generating line at a right angle e.g., will always determine a circle in the 2 cases 1stturning in the direction A, 2nd direction B. –

[…]

As there is gradually less differentiation from axis to axis., i.e. as all the axes gradually disappear in a fading verticality the front and the back, the reverse and the obverse acquire a circular significance […]

Further examples possibly related to the idea of ruled surface can also be found in the White Box, such as the following:

On an infinite line let us take two points, A and B. Let us rotate AB about A as hinge. AB will generate some sort of surface, i.e. either curved, broken or plane

or even this one:

Elemental parallelism: repetition of a line equivalent to an elemental line (in the sense of similar at any point) in order to generate the surface.

click to enlarge

Figure 25

Marcel Duchamp, Sad Young Man on a

Train , 1911

Figure 26

Marcel Duchamp, Nude descending a Staircase no. 2, 1912

The formula of Elemental parallelism was not a sterile speculation, but one of the most important conceptual foundations of a whole creative period: we know that Duchamp used it for capital painting, such as Sad Young Man on a Train(1911) (Fig. 25) or Nude descending a Staircase (no. 2) (1912).(Fig. 26) He carefully explained it in the dialogue with Pierre Cabanne .

As an example of how a ruled surface can be generated, imagine a luminescent straight thread moving about in the darkness; also imagine a camera with the shutter opened, to capture the luminous trail left on the film by the moving thread. This trail could be an example of ruled surface. The example is not chosen by chance: this explicative metaphor is used by E.J. Marey in one of his photography books . Duchamp was interested in similar photographic experiments (chronophotography), and scholars already related the painting of 1912 Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) to chronophotography.

Thus, for a moment let us think of the threads of the Grinder as a suggestion of straight lines moving about, while the rollers are grinding, generating trails corresponding to several kind of ruled surfaces.

The connection between the glued threads of the Grinder and the duchampian concept of elemental parallelism has been already stressed by Craig Adcock, who also recalled that Duchamp spoke of the threads as generatrices

Let us start with the simpler example: what is the geometric locus of the diametric threads of the circular bases of the rollers, as they rotate around the axis of the Grinder, without rotating around their own axis? Animation 2 shows a rotating roller. The surfaces described by the diametric blue lines are one-sheeted hyperboloids.

Animation 3 : shows that as the diametric lines vary their inclination, the hyperboloids gradually change their shape, giving rise to the degenerate case.

Animation 2

Animation 3

The genesis of a single-sheeted hyperboloid by means of a rotating straight line is also displayed by Marey in his already cited photography book which Duchamp surely knew (Fig. 27).

click to enlarge

Figure 27

The genesis of a

single-sheeted

hyperboloid displayed

in Marey’s book

Figure 28

Two single-sheeted

hyperboloids forming a

special type of gearing

Figure 29

Marcel Duchamp,

Coffee Mill ,

1911

Look now at Fig. 28: being the single-sheeted hyperboloids (doubly) ruled surfaces, it is possible to use them to create a special type of gearing. The interest of Duchamp in similar devices is documented by a painting which can be considered as the most direct antecedent of the Grinder: the Coffee Mill (1911),(Fig. 29) which clearly displays the gearing machinery allowing the device to work.

We already recalled that Linda Henderson thoroughly documented that theChocolate Grinder is strongly related to electromagnetism and wireless telegraphy: it is its second identity, after the first one as both a true and metaphoric grinder (connected with the autoerotic activity of the Bachelor, resumed with the slogan: The bachelor grinds his chocolate himself). Now, I like the possibility of a third identity of the Grinder, as a geometric device to generate ruled surfaces.

Maybe it can be seen as a flight of fancy, but not so much, after all; read indeed once again the Green box note about the geometric properties of theBachelor apparatus:

Principal forms, imperfect and freed

The principal forms of the bachelor apparatus or utensil are imperfect:

Rectangle, circle, square, parallelepiped, symmetrical handle; demisphere.-i.e. these forms are mensurated (interrelation of their actual dimensions and relation of these dimensions to the destination of the forms in the bachelor utensil.)

In the Bride – the principal forms will be more or less large or small, no longer have mensurability in relation to their destination: a sphere in the Bride will have any radius (the radius given to represent it is “fictious and dotted.”)

Likewise, or better still, in the Pendu Femelle parabolas, hyperbolas (or volumes deriving from them) [emphasis mine] will lose all connotation of men-surated position.

The question is: where are those hyperbolas and volumes deriving from them (and the corresponding surfaces, we could add) which, once passed into theBride realm will lose their connotation? Are they maybe the ones generated by the Grinder? It is possible.

Accepting this hypothesis, let us take some further step.

What happens if, while rotating around the Grinder axis, the roller also rotates around its own axis? Applet 13 will help visualize the possible resulting surfaces for such a composition of motions.

The different possible outcomes depends on the different sliding component in the motion of the rollers (remember indeed that in their motion rollers also slide on the Chassis). It means that, once a complete turn around the Grinder axis is completed, the rollers also turn around their own axis by a certain variable angle ω, whose amplitude depends on the sliding component.

Look finally at Applet 13: at its opening, the parameters are fixed in order to have the roller making a half turn around its own axis, while making a complete turn around the axis of theGrinder.

The surface described by the diametric line of the major base of the roller is a Moebius band.

At the bottom of the figure you find two green points which can be dragged.

By dragging the upper one the roller will rotate and make a complete turn around the Grinderaxis: you can see that the diametric line actually rules the band. As you drag the lower green point you simply modify the ω parameter and accordingly the locus surface will gradually change its shape, giving rise to more complex bands.

A further step could be taken by observing the surfaces obtained by the longitudinal lines of the rollers as generatrices. Applet 14 visualizes them. Once again the two green points can be dragged, with the same meaning as before.

Now the question is: accepting the present hypothesis about the Grinder, what could be the meaning of the surfaces generated by it, in the general project of the Glass? In my opinion surfaces such as the Moebius band, with their topological properties, could be a means for theBachelor to emulate the higher and more complex space of the Bride; it could be a sort of bridge, between the Bachelor and the Bride realms: remember indeed that the Bride is characterized by topological properties where the metrical traits governing the lower half of theGlass lose their meaning. The same holds (all the more reason) for the more complex bands obtainable with the Grinder.

To be precise, I don’t mean that Duchamp thought exactly of the Moebius band (or of similar and possibly more complex surfaces), but it is possible that he could imagine similar figures, maybe knowing neither their name nor their status of well-defined and studied geometrical objects. Possibly he guessed some of their strange properties; after all we have a number of evidences of its astonishing geometric imagination. Jean Clair already discussed some works of Duchamp referring them to well defined topological objects (such as the Kleinian bottle). Also Clair informs us that in the 60’s Duchamp discussed the properties of such topological objects with the French mathematician Le Lionnais. Following this suggestion I discussed other possible examples, referable to the properties of both the Kleinian bottle and the Moebius band.

In conclusion we could think of the Grinder as a ruled surfaces generator, or better, as a true surfaces grinder. The complex surfaces generated by Grinder’s motion could emulate the topological essence of the hyperspace of the Bride realm in the higher part of the Glass. The thesis is supported by some facts:

1. Notes from both the Green Box and the White Box (cited above) prove that Duchamp knew and used the concepts of ruled surface and quadric surfaces (at least on a qualitative level);

2. The idea of ruled surface is strictly connected with the practice of chronophotography which Duchamp praised and in a way used;

3. The surface of the rollers is carefully ruled by the threads sewn on the canvas, and as theGrinder is supposed to work, they rotate moving about in several complex ways; and, above all, the Grinder actually works as a surfaces generator;

4. It is proved that (at least) in the 60’s Duchamp knew at some qualitative level both the Moebius band and the Kleinian Bottle;

3.3. The Sieves’ perspective: a possible antecedent of Duchamp’s optical devices

Let us now consider the Sieves (or Parasols) and their function in the Bachelor apparatus. TheGreen Box notes describe the process which produces the so called Illuminating gas; as it leaves the Capillary tubes, it is then cut into bits, called spangles, which must run through the circular pathway of the Sieves:

As in a Derby, the spangles pass through the parasols A,C D.EF…B. and as they gradually arrive at D, E, F, … etc. they are straightened out, i.e. they lose their sense of up and down ([more precise term]). – The group of these parasols forms a sort of labyrinth of the three directions. –

The spangles dazed by this progressive turning. Imperceptibly lose [provisionallythey will find it again later] their designation of left, right, up, down, etc, lose their awareness of position.

By this way, the spangles, straighten out

[…] like a sheet of paper rolled up too much which one unrolls several times in the opposite direction

lose their sense of space. The way it happens is described as a loss of distinction between left, right, up, down, etc. as they pass through a labyrinth of three directions.

The following note from the Green Box makes clear that in Duchamp’s thought the identifications left-right, front-back, hi-low and so on are connected with the suggestion of a higher dimension::

[…] the front and the back, the reverse and the obverse acquire a circular significance: the right and the left which are the four arms of the front and back. melt. along the verticals.

the interior and exterior (in a fourth dimension) can receive a similar identification.

Hence we can think that the circular pathway through the Sieves and the consequent loss of distinction between opposite orientations could be somehow connected with the suggestion of a higher dimension.

The pathway followed by the Spangles is strictly circular, because the seven Sieves (originally they were six and semi spherical) have nine holes (originally eight) which repeat exactly the shape of the polygon connecting the nine (originally eight) Malic moulds, where they come from.

The sieves (6 probably) are semispherical parasols, with holes. [The holes of the sieves parasols should give in the shape of a globe the figure of the 8 malic moulds, given schematic. by the summits (polygon concave plane). by subsidized symmetry]

Thus the Sieves convey the Spangles according to well defined circular trajectories.

Applet 15 shows the pathway of 5 possible Spangles, assuming for simplicity five arbitrary convenient positions of the holes. The blue point can be dragged to move the Spangles through the Sieves. The actual course of the Spangles is semicircular, but Applet 15 displays a complete turn, in order to emphasize some aspects we will discuss as we shall go along.

Applet 15 helps understand why the dazed spangles lose the sense of up-down and left-right (follow for instance the course of the blue one); in addition it displays a strong depth effect due to perspective rendering of the Spangles in motion.

click to enlarge

Figure 30

Five semcircumferences used by

Duchamp to perform the

perspective drawing of the cones

Figure 31

Because of the perspective,

the arcs are not concentric:

their centers are the points A, B, C.

Let us now return to the perspective of the Sieves. Particularly let us consider the Yport sketch of 1914. The following Fig. 30 summarizes those, among its features, relevant in this context.

We clearly see five semcircumferences used to perform the perspective drawing of the cones. Four of them were used to rotate four diametric points of the first ellipse, in order to easily obtain the corresponding transformed points of the remaining ellipses; the fifth arc was used to obtain the centers of each ellipse, starting from the first. Maybe other circumferences were used, also considering how perfectly the ellipses are drawn; however the sketch doesn’t show any trace of possible further arcs. Note that, because of the perspective, the arcs are not concentric: their centers are the points A, B, C, visible in Fig. 31, which also displays the complete circumferences.

I used for convenience just these circumferences as circular pathways of the spangles in Applet 15; according to the original project by Duchamp, nine similar circumferences must be used (one for each of the nine holes).

The White Box contains notes which specifically connect linear perspective with circular shapes, by means of the concept of gravity:

Gravity and center of gravity make for horizontal and vertical in space3

In a plane2 – the vanishing point correspond to the center of gravity, all these parallel lines meeting at the vanishing point just as the verticals all run toward the center of gravity.

This association between perspective and gravity (which interestingly and meaningfully was made in the same way by Klee) leads Duchamp to the following conclusion:

Resemblance –

Between a perspective view and a circle –

The vanishing point and the center –

To what in a perspective view would the

Circle itself correspond?

Horizon

Elsewhere in the White Box we also read:

Difference between “tactile exploration” or the wandering in a plane by a 2-dim’l eye around a circle, and of this very circle by the same 2-dim’l eye fixing itself at a point. Also: difference between “tactile exploration,” 3-dim’l wandering by an ordinary eye around a sphere and the vision of that sphere by the same eye fixing itself at a point (linear perspective).

Here Duchamp adds the motion as a further key ingredient in the perception of higher dimensions of space. Perspective representation and vision must be integrated by the motion of the eye in order to reach a better representation and understanding of higher dimensional objects:

A 3-dim’l tactile exploration, a wandering around, will perhaps permit an imaginative reconstruction of the numerous 4-dim’l bodies, allowing this perspective to be understood in a 3-dim’l medium.

Perhaps, the rotational motion of the Spangles through the Sieves may be intended as a suggestion of a wandering or tactile exploration of the space surrounding the Sieves, or, in general of the medium which the Glass is immersed in.

Following this course, the next step seems to be quite obvious: maybe the same effect could be reached if, instead of the wandering around an object, this very object could turn in front of the observer which remains in a fixed position.

In our case, what happens if the circumferences conveying the Spangles rotate around a fixed center (not necessarily one among points A, B, C in Fig. 31 in front of us?

Applet 16 illustrates the outcome: a set of seven eccentric circles (which I used before for the perspective construction) rotate around a center near to their own centers, which however doesn’t coincide with any of them. Use the blue point to fix the center of rotation into the desired position; drag the red point to shift the set of circumferences backward or forward; finally drag the green point to rotate the set of circles.

The depth effect is quite remarkable, and is further reinforced if the circles are colored, like in the following Animation 4.

Please refresh the page, if the animation stops

Animation 4

Thus we passed from a true 2D plane to the illusion of a 3D space. Hence, once again we have the emulation of the higher dimensionality of the Bride realm.

Only speculations? Possible, but it is exactly what Duchamp did a few years later with the filmAnemic Cinema (1925) (Fig. 32) and especially with the optical devices such as the Rotary demisphere (1925) (Fig. 33) and the Rotorelief (1935). (Fig. 34)

click to enlarge

Figure 32

Marcel Duchamp, Anemic Cinema, 1925

Figure 33

Marcel Duchamp, Rotary demisphere, 1925

Figure 34

Marcel Duchamp, Rotorelief, 1935

There Duchamp used once again sets of eccentric circumferences, which while rotating produce remarkable effects of depth (see for instance Animation 5, where a facsimile of the optical disc named Verre de Boheme, 1935 produces the effect of a three dimensional stemmed glass). The effect of depth produced by the Rotorelief has no relation with the stereoscopic vision; on the contrary it is even more surprising if seen with a single eye.

Please refresh the page, if the animation stops

Animation 5

Animation 5

Interestingly scholars generally don’t consider the connection of the Rotorelief with the previous efforts of Duchamp in perspective, but I think it is an important element to consider, as Adcock already carefully stressed. Let us look once again at Animation 5. We see a 3D stemmed glass rotating in front of us, and it happens also because our mind perceives the set of circles as a Gestalt, and this can be possible all the more reason if the circles have some perspective consistence. Duchamp himself makes clear this point talking about his Rotorelief :

Thanks to an offhand perspective, that is, as seen from below or from the ceiling, you got a thing which, in concentric circles, forms the image of a real object

Thus, once again we have a strict correspondence between rotary motion, perspective, and suggestion of higher dimensions, with the optical illusion of depth, known as stereokineticeffect.

Indeed the rotating circles were drawn on the same sheet of paper (the Yport Sketch) and implicitly are present on the same sheet of glass; thus they actually belong to a plane; however in the perspective fiction they belong to different planes (parallel to each other) which determine a 3D space. Now, if the stereokinetic effect allows us to pass from the 2D plane to a 3D space, then according to the perspective fiction in the meantime we also pass from the ordinary space to a hyperspace.

Concluding this section, we shall consider an additional interesting feature of the Sieves which is to be stressed.

With their semicircular course, the circular bases of the conical Sieves ideally generate an half torus.

click to enlarge

Figure 35

If we identify the

diametrical points of a torus,

the surface we obtain

is a Kleinian

bottle.

With reference to Fig. 35, consider for a moment the whole torus, and its centre of symmetry C; also consider the couples of symmetric points of the torus, such as P and P’, or Q and Q’ and so on; call the points of such couples diametrical points. The loss of distinction (described above) between left-right, up down and so on, can be expressed in terms of identification of diametric points of our torus. Now, it is known that if one identifies the diametrical points of a torus for each possible couple, the outcome is a surface topologically equivalent to the Kleinian bottle. For those interested in the subject, it is clearly and simply presented in a classic text of David Hilbert .

Thus let us reconsider the notes dealing with the Spangles and their run through the Sieves, which I reported at the beginning of this section. The loss of distinction (or identification) between left and right, up and down, interior and exterior already interpreted in terms of reference to higher dimensions, can also be interpreted in terms of possible reference to the topological properties of a Kleinian bottle.

The different possible interpretations are not in conflict; on the contrary, they are somehow related, if we think that only in the fourth dimension the Kleinian bottle could be properly built.

Hence we can think of the Sieves machinery of the Bachelor apparatus as a further emulation of the topological properties of the Bride realm.

In conclusion I suggest three things:

first, we have some further evidences that coupling perspective and rotary motion allows theBachelor apparatus to emulate the higher dimensionality of the Bride realm;

second, the perspective construction of the Sieves could be seen as the most direct and relevant antecedent of the successive optical devices;

third, the Sieves could be thought of as a sort of topological apparatus which returns objects with non ordinary properties (such as the Kleinian bottle); thus the Sieves could also be considered as an apparatus emulating the topological properties of the Bride realm.

3.4. Rotating the Water Mill: an unexpected further bridge toward the fourth dimension

The Water Mill perspective offers a further unexpected surprise.

Let me start with the description of the course which led me to the serendipitous discovery about the Water Mill that I will describe in this section; indeed I think this very course contains in itself some insight about the way one could possibly approach the Glass in particular and Duchamp in general.

Once the perspective of the Water Mill was obtained with Cabri, it was only a question of few additional contrivances, to allow the wheels to rotate, thus I did it.

In order to better appreciate the rotary motion of the Water Mill wheels, I filled the polygons corresponding to the eight paddles (which originally were transparent) with a solid grey color.

The unexpected outcome is displayed in Applet 17. What kind of motion was there? What happened to the Water Mill? Was it turning forward or backward?

Along with the widely explored category of the 3D impossible objects, do we deal here with a new category, that of the impossible motions?

After a few moments I realized what the problem was:

The grey filling color is opaque, and if there is overlapping of paddles, each new filling operation causes the covering of the previously filled paddle. As the animation is running, for each frame Cabri repaints the screen, and the paddles are repainted accordingly, following the same order used to fill them the first time. So, it happens that from time to time, the order followed by Cabri for filling the paddles can be the right or the wrong one. If it is right, the paddles are drawn consistently with their position and with the forward motion (the foreground upon the background ones). In the contrary case the filling order is wrong, so that paddles which actually must be in background, are filled as they were in foreground and vice versa, and the global outcome is the perception of a backward motion. In addition, consider that originally the paddles were filled by chance, without a precise order, so that the animation actually shows a continuing and unpredictable change of direction.

click to enlarge

Figure 36

Impossible Water

Mill wheel

Now look at the static picture of the Water Mill in Fig. 36 (it is a single frame captured from Applet 17). In spite of its correct perspective, we face an impossible 3D object, similar to that of Escher’s print Belvedere, based on the Necker cube. Indeed Fig. 36 shows a similar situation, namely the simultaneous presence of two different and inconsistent versions of the same object.

The first version is based on the perspective shortening of the background paddles compared with the major ones in foreground.

The second version of the Water Mill wheels is based on the reciprocal coverage of the elements: in our mind the element which covers another isover, and the covered element is under.

Thus our perception continuously oscillates between two different possible choices, each one corresponding to a different orientation of the Water Mill.

These two possible simultaneous orientations of the same object are specular: it means that no rigid motion inside the ordinary 3D space allows us to overlap these figures, which are inversely congruent. To physically obtain this result, we would have to rotate the figure in the forth dimension. Thus, once again the mental effort we make to invert the figure corresponds to a rotation in the fourth dimension.

The interesting thing is that the key element to achieve such a result is just the rotary motion, coupled with the perspective rendering of the wheels with their paddles, and not the coverage order of the paddles (which however propitiated the discovery) as we shall see.

Indeed, if you look at the static Fig. 20 and try to do the mental inversion of the object, is a lot harder than do that by observing the animated Applet 17.

The following applets are intended to enable the reader, step by step, to progressively lay aside the coverage order of the paddles, but always maintaining the optical effect of inversion.

Using Applet 18, you will learn to follow a single paddle (the red one, in this case) and to perform a stable mental inversion each time the paddle reaches its higher and lower positions.

Applet 19 will help you fix a single paddle (the one with the red border) but laying aside the coverage order, because the paddles are drawn transparent.

Finally Applet 20 shows a transparent Water Mill which you can invert without any help.

Use it to convince yourself that just the rotary motion of the paddles allows you to easily invert the object: stop it by passing with the mouse over its area and then leave it. Try now to invert the static frame. Once again it is a lot harder than with the moving picture.

With patience you will obtain a surprising result (even though only for a few instants at once):at the same time the wheels will rotate forward and backward, the paddles will be over and under, in front and back, the view point being both from the left and the right of the wheels.

This meaningfully agrees with some details of Duchamp’s speculations about the fourth dimension. Remember the already-cited note from the Green Box:

[…] the front and the back, the reverse and the obverse acquire a circular significance: the right and the left which are the four arms of the front and back. melt. along the verticals.

the interior and exterior (in a fourth dimension) can receive a similar identification.

As a further detail consider the Green Box describing how the Water Mill works: one of its interesting features is that the rotation of the water wheels determines the onanistic left-right motion of the whole Chariot (which sustains the water wheels): this motion in fact could propitiate the left-right shifting of the viewpoint from where the wheels are viewed.

As a matter of fact, if you look at Applet 20 by shifting to the left and the right your head according to the rotation, it is a lot easier to make the required mental inversions than holding the same fixed position.