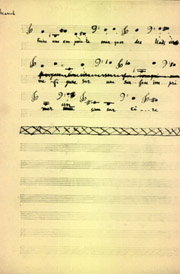

click to enlarge

Portrait of Erik Satie

© 1999 Archives Erik Satie, Paris

Satie, a French composer, studied music at the Paris Conservatory Schola Cantorum. He was the pupil of Vincent D’Indy and Albert Roussel.

Against the romantic Wagnerian style which was incapable of expressing a French sensibility, Satie developed a controlled, abstract and seemingly simple style. His music, in general, features a removed, unaffected beauty. Although his early works anticipate the harmonic innovations of some impressionists, such as Debussy and Ravel, his later compositions foretell the neoclassicism of the early 20th century. Satie often disguised his artistic intention with comical humor, adding nonsense programs or whimsical titles such asThree Pieces in the Shape of a Pear (1918). The “avant-garde” in Satie’s aesthetics is found not in his often very bland music but in the ways that his compositional simplicity challenged the ultra-seriousness of the musical establishment.

click to enlarge

Marcel Duchamp and Man

Ray in René Clair’s

1924 film Entr’acte

Clair,Satie, and Picabia

during the filming

of Entr’acte, 1924

A widely experimental musician, Satie composed a musical score in 1924 for a twenty-two minute avant-garde film entitled ENTR’ACTE, written and produced by Francis Picabia, directed by René Clair. The cast of the short film included Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray and Satie himself. It was the first time a “shot-by-shot” musical composition had been written for a film. Satie meticulously examined the film and wrote a composition designed to synchronize exactly with it and to have rhythms match the flow of the editing of the film. It is certain that none of the artists involved in the film were interested in providing the audience something that was expected. (They used an element of pleasant rather than unpleasant surprise.) The music of Satie was recorded by Henri Sauguet and added to the silent print in 1967.

The music playing here is cited from SATIE/3Gymnopédies & Other Piano Works, 1984, no. 17 – Le Picadilly. Beginning in 1888, Satie was a pianist in a number of Montmartre cafés (which were the meeting places of musicians as well as of writers and painters.) Around 1900, he produced several first-rate café songs. Le Picadilly is one of the music-hall pieces composed during this period. Satie’s contribution to the world of popular entertainment was substantial.

click to enlarge

Erik Satie by Francis Picabia

It is hard for us now to imagine how astonished the Paris audience must have been with Satie’s music which was so different from the lush compositions of his peers, Franck and Saint-Saens. Satie’s audience must have been especially astonished when the music they heard was accompanied by the composer’s bizarre titles and performance instructions. Yet Satie’s compositions are still unlike anything else in the piano literature and still full of touching and evocative delight and charm.

< Music >