click to enlarge

Robert Barnes in the 1950’s and 1960’s

(from left to right)

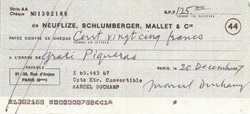

The American painter Robert Barnes, recently elected member of the American Academy of Design, is a very private person and doesn’t care much for publicity. It was only after many phone calls and letters that he finally agreed to a lengthy interview in his studio in Bloomington, Indiana, on January 27, 2001. Besides a brief book review of Calvin Tomkin’s biography of Marcel Duchamp (Duchamp: A Biography, New York: Henry Holt, 1996) published in Blackwell’s Britain-basedThe Art Magazine in 1997, he had never before spoken about his close encounters with Duchamp and other Surrealists in New York during the 1950’s. Though refusing to be called “Duchamp’s last assistant” he admits that it was he whom Duchamp had asked to pick up the pig skin for Etant Donnes in Trenton, New Jersey*. The following interview, therefore, sheds some new light on the production of Duchamp’s final major work as well as his edition of Ready-mades in1964, and reveals heretofore unknown facets about Duchamp, and those who knew him at the time.

click to enlarge

Robert

Barnes visiting the Marcel Duchamp collection of

the Indiana University Art Museum, Bloomington, January 2001

click to enlarge

Figure 1

Marcel Duchamp, Given: 1The

Waterfall / 2. The Illuminating

Gas,1946-1966 (outside view)

Figure 2

Marcel Duchamp, Given: 1.The

Waterfall / 2. The Illuminating

Gas,1946-1966 (inside view)

Tout-Fait: There are a lot of questions that I want to ask you–about you and your art and the people you knew. Let’s just start withEtant Donnes (Fig. 1, 2), Duchamp’s final masterpiece that he supposedly worked on in secret between 1946 and 1966. You apparently knew about the piece before it was posthumously revealed at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1969?

Robert Barnes: Lots of people knew about it. I don’t know what this great mystery is. I am sure that Matta (1)knew about it. And if Matta knew about it, everyone in the world knew about it. Matta was a bigger blabbermouth than I was. But, you know, a lot of mystique about Duchamp and all of the legends and stories that have grown up around him were basically manufactured much later and Etant Donnes, well you know, I think it’s his masterpiece. A lot of people are critical of it. I think they are critical of it because it embarrassed them. But it is the bride fleshed out and it is the appropriate final production that Duchamp created. The secrecy — to tell you the truth — I don’t think is very important because everything about Marcel was secret and known, that’s the way he was.

Tout-Fait: And you were born in 1934?

Robert Barnes: Yeah, but I don’t admit it to many people.

Tout-Fait: You came to New York when you were 19 I think you said?

Robert Barnes: No, twenty-something.

Tout-Fait: Oh, you had married when you were 19. So you were introduced to that circle of artists by… how did you get to know them?

click to see video(QT,946KB)

download

QuickTime Player

Video 1

Interview

with Robert Barnes

(Excerpt), January 2001.

Robert Barnes:Through Matta.

Tout-Fait: And how did you come across him?

Robert Barnes: I met Matta when I was a young man in Chicago. It is interesting with people. You know who you can know, and you know who you can like, and there are affinities that are expressed without ever having an explanation. The same was true with Marcel, except Marcel liked everybody. But Matta and I just had an affinity and he was good to me, he was careful with me. He helped me, and there’s an interesting story to indicate this. He was staying in Chicago, in some hotel, and he invited me out to his place and I was delighted to go because, at that time, he was living with what I guess was said to be his wife, but I’m not sure she ever was: Mellite, a gorgeous French woman and I was totally in love with her. And I was delighted to go. I was more interested in her than in Matta at the time. When I was a young man, I was overly sensitive to things, and I found it difficult to eat when I was nervous. I was just sort of paralyzed. It was terrible on dates, because I could never eat when I was on a date. And I went to this dinner and Matta said to me–I was sitting there looking uncomfortable–and he said “You have a problem eating, don’t you, when you’re uncomfortable?” and I said, “Yeah” and he said, “So did I.” Now I don’t think he ever did. I don’t think Matta was ever uncomfortable. He said, “Let’s drink this wine.” And he had discovered a catch at a low price of a wine, called “Grand Echeseaux,” which he dearly loved; it was his favorite wine. He bought tons of it. And after a couple of glasses, I totally relaxed. What I am telling you is that Matta had a way of making you feel comfortable and that’s probably why he had nine wives because he made them feel comfortable and then uncomfortable later.

Tout-Fait:Now that was Matta. But I have to get back to Etant Donnes. You said you were not Marcel Duchamp’s assistant but he told you to get certain things for this piece.

Robert Barnes: I am uncomfortable with that story. Let me tell you that Matta did introduce me to Marcel the first time, that’s how it happened. He took me up to Duchamp’s apartment. It was in the 50’s, near Bloomingdale’s (2).

Tout-Fait: He was already married to Teeny then.

Robert Barnes: Yeah. But you want to go back to Etant Donnes. I would never admit this, but I went to New Jersey to get the pigskin.

Tout-Fait: He asked you to?

Robert Barnes: Yeah. And I didn’t know how to drive a stick shift and I didn’t have a driver’s license but I took this truck and I don’t know whose truck it was, probably some merchants, and picked up this pigskin.

Tout-Fait: He had already ordered it and just wanted someone to pick it up for him.

Robert Barnes: Yeah. The thing is, this is going to screw up all of your research because I think that this was his second pigskin. I think he had one before. I don’t know whether it was to patch. You know when I was on the scene it was late Etant Donnes, he was already in the process pretty much.

Tout-Fait: Officially he started working on it in 1946, and below the signature he writes 1966.

Robert Barnes: That’s way late. It was done sitting, gathering dust by then. It was in the ’50’s, ’56.

Tout-Fait: So how did he first introduce you to it?

click to enlarge

Figure 3

Duchamp,The Bride Stripped

Bare By Her Bachelors, Even

(the LargeGlass), 1915-23

Robert Barnes: Well I was at his apartment and he asked me if I’d pick up the pigskin and I did. But I knew about it before then, that’s the thing, everyone sort of knew about this thing and most people hated it and thought it was a waste of time. I loved it; you know I thought it was his masterpiece. Although the Large Glass (Fig. 3) is probably the monument but this is the masterpiece because it tested people’s ability to accept Marcel. Now we accept him.

Tout-Fait: Well a lot of people still don’t.

Robert Barnes:Well too bad.

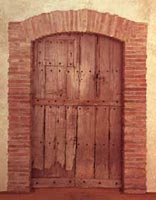

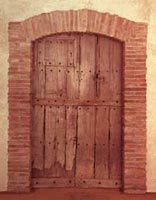

Tout-Fait: When you saw the piece, the door wasn’t there, the door came very late.

Robert Barnes: No. When I saw it, it was all over the place, it was in pieces. And my suspicion was that he put the skin on earlier and it cracked. He had a terrible time keeping it soft. There was a beauty shop downstairs and awful smells came out of that place it was enough to give you asthma and die just going up to Marcel’s studio. And I think he actually asked them about lanolin and skin softeners to use on his skin. No not on his skin, on the pig’s skin. My feeling is that either the pigskin that I got–which I never actually saw, it stayed in the brine — it might have been just to patch it. Do you know when they took it apart were there patched pieces?

Tout-Fait: Well as you can see in the Manual of Instructions (Figs. 4, 5, 6) here, you can disassemble it in certain points. But when you say it was all over the place, what do you mean by that?

Click to enlarge

Marcel Duchamp, Manual of Instruction for the Assembly of “Etant Donnes,”

(pages 46a, 62 and 64), 1966

Robert Barnes:There were pieces of it. It was not hard to see what it was. I don’t remember

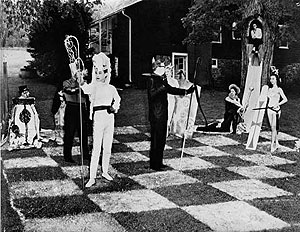

the branches. The thing I remember most about all this is the damn floor. Well it’s so appropriate and so ugly and the building was so awful, but that floor, made sense. There’s that movie of Richter’s (3),

8×8 (Fig. 7), with a giant chessboard and people walking on it. And I always thought that you almost needed to hop in that studio the way you hop from one square to another.

click to enlarge

Figure 7

Hans Richter,8×8,

1955-1958 (film still)

click to enlarge

Figure 8

Marcel Duchamp, Given: Maria,the

Waterfall and the Illuminating Gas,1947

Figure 9

Marcel Duchamp, Given: Maria,the

Waterfall and the Illuminating Gas,1947

Tout-Fait: Judging from the preliminary works (Figs. 8, 9), some argue that he first tried to construct Etant Donnes as a standing figure, was it always lying there?

Robert Barnes: Yeah. I don’t think it ever could stand and I don’t think he cared or wanted it to. He might have wanted to position it up a little bit so you had to look at the pudenda.

Tout-Fait: You can say pussy if you like.

Robert Barnes: I know you can say pussy but I don’t know¡¦

Tout-Fait: What do you think in terms of this thing being anatomically correct, do you think he took life casts?

Robert Barnes: No, he didn’t give a damn about whether it was anatomically correct. In some ways–I mean if you look at it as he intended, as a voyeur, somebody peeping through a hole–it is shocking because the pussy is not right and you look at it and you say, “oh wait, no this isn’t right” and you start adjusting. Marcel was smart enough to make you think that and also being hairless it was a little bit like kiddy-porn.

click to enlarge

Figure 10

Gustave Courbet,The

Origin of the World, 1866

Tout-Fait: But what you said with the spectator or the voyeur, looking at this and seeing, you

know you have Courbet’s Origin of the World (Fig.10)and there you have an anatomically more or less correct pussy (4), whereas Duchamp’s intentionally wasn’t right?

Robert Barnes: Well with Courbet, you know what you’re into, if I may pun a bit. In Duchamp you approach it with doubt, you’re not sure you want to be there or should be there, want to be there is maybe even more important. With Courbet you know what you’re thinking about, this is obviously a woman¡¦ With Duchamp you have the inaccuracies and the fact that the body is not right at all. The whole wig thing. It’s all wrong but you look at it and start rearranging it and of course everything he did was like that and the attempts to explain Duchamp I think are terrible because it is alien to the point. And I think even Duchamp’s explanations, all the things he wrote, were misleading. I think intentionally misleading, done after the fact, and meant to feed people who want to be fed.

Tout-Fait: Why would you think he intentionally constructed a torso that you notice is not a torso but rather some distorted figure. Why would he not try–if he uses all of these 3-D materials–why would he not try to aim for an anatomically correct torso?

Robert Barnes: Because he wasn’t an academician. If he wanted to make it anatomically correct he could have done that and it would not have had the same impact.

Tout-Fait: Because none of the men I know that are into women and look at this thing find it sexually arousing.

Robert Barnes: Oh, I do.

Tout-Fait: Oh you do?

Robert Barnes: I think it’s neat. The thought that you have is you sort of wish that women were built like that, were made like that, a little distorted, a little extra. But I’ll get off that subject quickly before I get arrested. I was always amazed at how many people were embarrassed by it and obviously that was the intent of the work. I mean all of these nitwits that looked at it and said it’s not worthy of Duchamp were the ones that he was out to get. And I loved it. You know I didn’t see it. I never saw it put together until much later.

Tout-Fait: But you saw it. The thing is though, when it was reviewed, when it was released to the public in 1969 at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, John Canaday of the New York Times already wrote at the time that Etant Donnes was “very interesting, but nothing new,” maintaining that in the light of artists like Edward Kienholz, Duchamp, “this cleverest of 20thcentury masters looks a bit retardaire.” In other words, it looked dated and surely wasn’t shocking anymore.

Robert Barnes: Because Duchamp was before and fed into this age that had to be shocked.Etant Donnes is not shocking, it’s embarrassing. Big difference. You look at it and you think “I should not be thinking this or looking.” And you’re not shocked but I mean no one can approach this piece of work without it clobbering him. And Marcel was very subtle.

Tout-Fait: He was very subtle. What do you think about him working with such a different media, all of the sudden coming up with this three-dimensional environment?

Robert Barnes: Why is it so different? He made the thing. His other casts of women are all leading up to this¡¦

Tout-Fait: Well that is one thing. When he did the casts¡¦

Robert Barnes: I never asked who it was. I suppose it was Teeny.

Tout-Fait: There are different stories about the casts.

Robert Barnes: I guess you’ll have to find the “castee” or “castette.”

click to enlarge

Figure 11

Marcel Duchamp,Female Fig

Leaf, 1950 (first version)

Tout Fait: Take the Female Fig Leaf (Fig. 11), for example. Richard Hamilton says that Duchamp told him he did these things by hand, whereas Duchamp scholars like Francis M. Naumann think that he actually took a live cast.

Robert Barnes: Oh, well he would have taken a live cast because it’s more fun.

Tout Fait: But who would that have been? Maria Martins(5)or Teeny or both?

Robert Barnes: Probably anybody–anybody who would lend her body.

Tout Fait: You know Duchamp toyed with the fourth dimension in the Large Glass. Do you think

there might also be something of that in the distorted body, by arriving–as Rhonda Roland Shearer has argued–at a higher level of representation because it is not just 3-D. But by rendering a body, somehow through distortion, thus incorporating movement in time–or do you think this is going too

far?

click to enlarge

Figure 12

George Segal, Lovers on

a Bed II, 1970

Figure 13

George Segal, Young Girl, 1972-73

Robert Barnes: Well if he had done it merely in 3-D, it would have been a George Segal (Fig. 12, 13). He wasn’t interested in that, he’s better than that. I don’t know if you’ve noticed it. But Duchamp was magnificent. He was so smart, so intelligent, his brain was so complex and that’s the best thing about him that I don’t think anyone¡¦ I think you can only approach appreciation to Duchamp and I don’t think his intelligence was where people thought it was. Everyone felt that Duchamp was ‘scientifically pure, he could think in mathematical ways.’ I don’t think he could add beans. I think Marcel was inventive because he was beyond science; he was beyond accuracy and Figures. He was beyond all that because then he could approach us; he could manipulate us. Being around Duchamp was always–I wouldn’t say challenging because he made people comfortable–but the thinking was rapid and he wasn’t the only one, Matta was quick, too. All of those people in the circle of Duchamp were quick.

Tout-Fait: And you were young and in their midst.

Robert Barnes: I was just a baby. I was a pretty kid. I didn’t ever approach them with enough reverence though. I felt like I just was interested. It wasn’t “oh the big artist.” Because it is like anything, if you know a celebrity, you are always shocked at how human they are. The first time I met Duchamp, I went with Matta, and Duchamp had a cold and the first thing I thought, “men of this stature don’t get colds.” And he was in his bathrobe eating honey out of a silver bee. Now if that wasn’t so much Duchampian as Ernstian or something Richter would have thought of. But it was weird because it was so appropriate and his apartment was always a place where¡¦ I wonder where all that stuff is, do you know?

Tout-Fait: I don’t know exactly, it went to the estate I guess.

Robert Barnes: But who was left in the estate after Teeny?

Tout-Fait: I believe Teeny’s three kids, Jacqueline Matisse Monnier as well as Paul and Peter Matisse.

Robert Barnes: What did they do with all of that?

Tout-Fait: Some of it was donated to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, other works were donated to the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris.

Robert Barnes: Can you imagine¡¦ you know he used to have an armchair that was done in needlepoint by Miro(6)?It was all so oily because he would always lean on it. It was his favoritechair. Could you imagine sending that to the Salvation Army?

Tout-Fait: Was it?

Robert Barnes: I don’t know. Every time when someone dies they give stuff to the Salvation Army. That reminds me of a gathering at Duchamp’s place once. All the people were staring at me. It was very uncomfortable. I don’t like being stared at. And Duchamp who was so sensitive, he knew that I was feeling uncomfortable. And he leaned over and he said to me “They are looking at you Robert, because you are sitting on a Brancusi” (7)–a little bench thing–and I started to get up and he pushed me down and said. “That’s what it’s for, to be sat upon. So let them look at the Brancusi and forget about yourself.” And I did.

Tout-Fait: Can you recall how many parts Etant Donnes was? How many parts when you saw it

there at his place?

Robert Barnes: No, the best thing I can remember about the place was the chess-board floor. I mean that’s very exciting, isn’t it, for history.

Tout-Fait: So the only time you helped him with it, was getting the pigskin? And how many times had you been to the secret studio on 210 W 14th Street?

Robert Barnes: Oh, lots of times. I lived just down below there for a while.

Tout-Fait: So you saw the progress that was made?

Robert Barnes: Yeah. And at the time I was working for Carmen DiSappio who was just down the street, so¡¦

Tout-Fait: So when works like Female Fig Leaf came out and those things that had to do with Etant Donnes that people could only place it with Etant Donnes later because they did not know about it. When you saw these pieces you already knew that they had to do with this kind of work?

Robert Barnes: The thing is that if you knew Marcel and you knew the people around them, this is a sequence that is so practical and natural, I mean these were horny people my friend. Matta was probably the horniest of all. He’s probably still trying to dick everything in sight. These were people who thought about sex. I mean, it’s all about sex–the gas. That’s what bothered me about Etant Donnes, what kind of light bulb is in the lamp?

Tout-Fait: It’s an electric light, though it’s supposed to be a Bec Auer, a gas burner.

Robert Barnes: Those long things?

click to enlarge

Figure 14

Marcel Duchamp,Portrait of Chess

Players, 1911

Tout-Fait: Yeah the long thing, that has a green light emanating from it, under which Duchamp experimented when he did the Chess Players in 1911 (Fig. 14). He painted in that green light. So although with Etant Donnes it is an electric lamp, it is supposed to be a gas lamp.

Robert Barnes: So that is maybe where the gas came in. The gas is like what we lately have discovered as pheromones, I think, which is a sort of sex gas.

Tout-Fait: What is sex gas?

Robert Barnes: Gas! And with Marcel, gas is always sex gas; it will get you. Worse than mustard gas, you’re done for.

Tout-Fait: Well, after all Etant Donnes‘ subtitle is 1) The Waterfall / 2) The Illuminating Gas. Do you recall having seen the painted landscape with moving waterfall used as the artwork’s backdrop?

Robert Barnes: No. I think the scene was there but I don’t remember anything happening back there; it was dark. I’m embarrassed to say it, but I didn’t focus on much of it then.

Tout-Fait: But you and Duchamp saw each other often? He was at your apartment and he liked the way it was built. What’s the story about that?

Robert Barnes: Yeah, I lived on Kenmare Street. It’s an architectural museum now or something. It is right across the street from the Broome Street police station. Downstairs was a tire store and there were these troll-like men who repaired tires down there and they had these vats where they would test to see if they were leaking. It was something right out of an opera by Wagner except that the blacksmiths were vulcanizers, which is perfect. And upstairs I had my loft, which was illegal, and Marcel loved it because it was. It had a door like Etant Donnes, a shackled door, and the little place was a mess but I had put in plumbing and we would all go down to Hester Street and buy plumbing supplies. We all got glass-lined water heaters that rusted but one of the joys of the place was that we couldn’t put an elbow in the tub, so it went straight. And we discovered that when you let the water out of the tub, it would explode downstairs in the tire tub. It was kind of Duchampian.

Tout-Fait: But he came by and visited you?

Robert Barnes: Yeah, not very often.

Tout-Fait: You were there in the early ’50s and you stayed in New York for how long? You were already married by then and you lived with your wife who was probably young and beautiful at the same time. So were the artists that you knew fond of her as well?

Robert Barnes: Yeah, Matta was. He wanted to steal her.

Tout-Fait: But Duchamp wasn’t hitting on her?

Robert Barnes: I wouldn’t have known if he was. She would have, but I wouldn’t have. Actually my wife was, at the time, beginning to show some symptoms of mental problems, so she didn’t go places. Her contact was rather limited.

Tout-Fait: So, you were there at the time when fame started setting in for Duchamp. There were more and more people approaching him. In this regard you mentioned something about “Mr. Availability.”

Robert Barnes: I think that was Teeny’s term. He was interested, I think, that was it. I don’t know why anyone paid attention to me because I was really wet behind the ears. He was awfully nice to me and listened to me and I don’t think I had much to say.

Tout-Fait: But they liked to have you around.

Robert Barnes: Yeah, I think I was decorative and I think they thought of me as maybe being someone to follow. Not follow, no, there was never any hint that I would follow anybody.

Tout-Fait: Well you were doing figurative oil on canvas and Duchamp, probably the others too, appreciated what you were doing since everyone else had stopped doing that. You said Duchamp liked the painting that was at the Whitney, your Judith and Holofernes of 1959/60. Taking into account his phobia regarding oil on canvas, did he encourage you to continue in that vein?

Robert Barnes: Yeah, he was very encouraging… because Duchamp had caused this disaster in the art world. Even during his lifetime he was beginning to realize that this was really an uncomfortable and ugly situation, people who mistook novelty for invention. And I think he’d like someone who ¡¦ well his whole bet was to follow what you are. I couldn’t be like him, I couldn’t even be like the surrealists. I certainly enjoyed their thinking, but I couldn’t go that way. I just did what I did and I still am. It makes you unpopular, maybe for a lifetime, but I’d rather do that than be popular and doubt what I am.

Tout-Fait: So that’s a quality he could appreciate.

Robert Barnes: He could appreciate that in anybody. Well, look at the people he liked. He did not have great taste in art. He loved a guy named Cremonini. Well Cremonini was a terrible artist. He was Italian and did those kind of long neck people with scrubby faces that didn’t have features.

Click to see video (QT.878KB)

Video 2

Interview with Robert Barnes

(Excerpt), January 2001.

Tout-Fait: Why do you think that he liked that kind of thing?

Robert Barnes: Well he liked him. He would have him over.

Tout-Fait: Well that’s always what he said. Look at the individual and not the art.

Robert Barnes: Well Cremonini was not likeable either. He was very conceited. Knobby head, that was very popular in those days and everyone did that. I think maybe one of the best and the worst thing Marcel offered people was a lack of discrimination. He didn’t discriminate. In doing so, he made the world easier, but by opening up, eliminating, abolishing decision-making tactics in deciding what is art, I think he created a terrible disaster. Because we don’t know what the hell we are doing, there are no standards. The standard now becomes fame or money, neither of which Marcel really cared about. He liked it but he did not ever pursue it. As a result, we have all of these people who want to be seen, and Marcel never wanted to be seen, he almost had to be picked out of life to be seen. I think, I don’t know what he would think if he were alive today, be amused, because he didn’t discriminate. He had this idea once, it comes from a conversation we had so I don’t know if it ever got said again. He wanted to know if we could decide what is art by having a vote. Have you ever heard that idea of his?

Tout-Fait: No.

Robert Barnes: Well he was going to have a world vote and everyone in the world would vote on what is art.

Tout-Fait: So they would get a little questionnaire?

Robert Barnes: Yeah and maybe something, pictures or something, but he thought it would be too hard to find pigmies and so he decided the only way to really get a democratic view of what art is was to have his questionnaire circulated in barber shops. In those days barbershops were not hair salons, they were just barbershops. You read dirty books and magazines and bought rubbers and it was easier than going to the drugstore. He liked those places and he thought that was probably the most democratic.

Tout-Fait: Only men would go there though.

Robert Barnes: Well I suppose he might have let the beauty parlors do the same thing. But that’s how he’d find out what art was.

Tout-Fait: Did anyone follow up on that?

Robert Barnes: No, you didn’t need to. The idea was good enough.

Tout-Fait: At the time you met him, most of the ready-mades were already lost, they only existed in old pictures, he made or bought a few reproductions in the1950s, then he came out with this edition in 1964 collaborating with the Milanese dealer and scholar Arturo Schwarz. Do you have any thoughts on the 1964 edition of the ready-mades?

click to enlarge

Figure 15

Marcel Ducham,The

Locking Spoon, 1957

Robert Barnes: First of all, the ready-mades were always being readymade around Marcel. I mean,

things were always being put together or glued, like the spoon on the doorknob(Fig. 15) (8).

You don’t seem to come across any mention of the antlers at the top of the stairs.

Tout-Fait: No, what about those, what stairs?

Robert Barnes: Well they were right at the top of the stairs of his apartment near Bloomingdale’s on the East side. And that’s the apartment that had the great mailbox, Duchamp, Matisse, and Ernst. Art history’s mailbox, really. At the top of the stairs was a set of antlers, really at a dangerous height, so you were always afraid that somebody would come up too fast and get impaled but I think that was the purpose.

Tout-Fait: You could hit your head?

Robert Barnes: It was right about here [motions in front of his chin]. You sort of had to get around it. I remember another thing Duchamp had made. One time he had a way of telling what time it was with the help of mirrors. Either the clock was outdoors or indoors, I can’t remember where the clock was. But he had one mirror at the clock, there’s another that would reverse, and then there’s another that would reverse it back.

click to enlarge

Figure 16

Marcel Duchamp,The Clock

in Profile, 1964

Tout-Fait: Well he wrote that note of a clock in profile that you can’t tell the time from a clock in profile (Fig. 16). Maybe the idea with the mirrors circumvented that somehow. Did he have that installed in his apartment?

Robert Barnes: Yes.

Tout-Fait: Only temporarily?

Robert Barnes: I don’t remember what happened to it.

Tout-Fait: How many mirrors?

Robert Barnes: Three or five. It had to be an odd number.

Tout-Fait: From a clock tower?

Robert Barnes: No I don’t think so. I don’t know where the clock was. I’m old. That was forty years ago.

Tout-Fait: But what did he do with the antlers. What was the thing with the antlers? He just had them there?

Robert Barnes: Well it was in the hallway outside of the door.

Tout-Fait: Were things hanging from them?

Robert Barnes: No. It would be great to hang things from. His house was always filled with odd little things set up. They all did it. Matta did it too.

Tout-Fait: But the ready-made edition in 1964, why did he do that?

Robert Barnes: I was mad about that.Tout-Fait: You were not in New York anymore?

Robert Barnes: No I was away. And I said to him, “What on Earth possessed you?” Everyone thought that Arturo Schwarz initiated it as a moneymaking venture. I don’t know maybe it was moneymaking. It certainly would be for Arturo.

Tout-Fait: You went to Duchamp, you approached him, and you asked him this?

Robert Barnes: Yeah, I said that I couldn’t understand why he did it. And he explained that it was… I mean, I can make a parallel between the bride in The Glass and the bride fleshed out in Etant Donnes. It goes full circle. The bride is not fleshed and then becomes flesh. With the ready-mades, they were junk and their traversing of time brings them to commercial objects. He told me he was going to have the opening in Macy’s, but I think he was joking or didn’t know it, because they didn’t do it.

Tout-Fait: So when you asked him, what did he say why he did it?

Robert Barnes: That’s what he told me. It was a perfect transit of the readymade from discovery to the crassness of just being a commercial object and it is very interesting that something that was nothing becomes something by our commercial standards, and we judge by money. I mean we were discussing his urinal today. How much did you say that sold that for?

click to enlarge

Figure 17

Marcel Duchamp,Fountain,

1964 (1917)

Tout-Fait: An example of the 1964 edition (Fig. 17) went for a little bit above $1.76 million in November 1999.

Robert Barnes: That wasn’t even the original. Here’s a thing where an idea becomes $1.6 million.

Tout-Fait: $1.76 million.

Robert Barnes: The traversing of time, and everything in Duchamp was about the process of transit, it brought a piece of junk toilet to someone who’s very wealthy or a museum’s halls. But it is still worth nothing. But someone paid one point something million.

Tout-Fait: In this case it was the Greek collector Dimitri Daskalopoulos, actually. Why would you think it is impossible for a lot of people to succeed in doing research on the original ready-mades –which Duchamp supposedly bought from stores–scholars like Thomas Zaunschirm or William Camfield writing an entire book about Fountain, or Kirk Varnedoe in 1990/1991, doing the High and Low: Modern Art & Popular Culture show at the Museum of Modern Art trying to find the original Comb (Fig. 18). Rhonda Roland Shearer is continuing to track down the original objects but you just can’t find them, even in the catalogues. Why would that be?

click to enlarge

Figure 18

Marcel

Duchamp, Comb,

1964 (1916)

Robert Barnes: Because they’re old junk. They’re old junk that lasts, pal.

Tout-Fait: Yeah, but the old catalogues, from the ’10s and ’20s, you should be able to find those things.

Robert Barnes: You’ve got the wrong catalogues, old catalogues get thrown away. But I just this love this business, “Oh, The urinal is a fountain of some¡¦” I mean art historians are bizarre. And again, I’m sure Marcel would be totally amenable to helping them create these bizarre attitudes, because it is again the transit of the thing into something else. It is transmuted and changed into something else. And certainly art history, if anything, transmutes art into something useless.

Tout-Fait: Art history keeps artists alive and Duchamp was always more interested in the audience that came after than in his contemporaries.

Robert Barnes: Self-glorification is what art history is about and “I have discovered this,” or “This is my area.” Crazy nitwits. “Duchamp is my area.” That’s goofy. But Duchamp would love that. He would love to have himself be their “area.” If there were any good looking ones, he’d like that too. But the whole idea of the transformation ¡¦ mystery, transformation, and manipulations–those were the things that Marcel was a magician at. That’s his magic.

Tout-Fait: Paul Matisse, who assembled Etant Donnes, in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, suggested that no one knew about the piece except Duchamp’s wife, Teeny, Duchamp himself, of course, and Maria Martins.

Robert Barnes: Well maybe it helped to sell it to people, make it more exotic.

Tout-Fait: When Bill Copley purchased Etant Donnes through his Cassandra Foundation (9), he knew about it too, so it wasn’t that big of a big secret. He purchased it and then gave it to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Now, we just talked about the erotic objects that were coming out in the ’50s. When you read reviews–and those people didn’t know about Etant Donnes in the making–they were, for example, described by the New York Times as “bizarre artifacts,” sexual objects of some sort. They didn’t know what to make of them.

click to enlarge

Figure 19

Marcel Duchamp,Bottle

Rack, 1964 (1914)

Robert Barnes: The Great Glass was a bizarre sexual object.

Tout-Fait: Almost everything, even the Bottle Rack (Fig. 19).

Robert Barnes: These were the horniest people on earth in an age where we were allowed to be horny without being arrested or sued.

Tout-Fait:I know, it’s a little sad nowadays. The first thing, even before he made the Female Fig Leaf, the Objet-Dard or Wedge of Chastity (Figs. 20, 21) –which he gave to Teeny as a wedding present–before all that he had already made the wedge section of the Wedge of Chastity, the inner sanctum of the Female Fig Leaf cast, if in fact it was a cast. It’s titled Not a Shoe (Fig. 22) and he gave it to Julian Levy (10) in 1950. Those two were pretty close, right?

click to enlarge

Figure 20

Marcel Duchamp, Dart-Object,

1951 (first version)

Figure21

Marcel Duchamp,Wedge of

Chastity, 1954 (first version)

Figure 22

Marcel Duchamp,Not

A Shoe, 1950

click to enlarge

Figure 23

Robert Barnes,Alfred Stieglitz,

1966 (as reproduced in Julien

Levy’s Memoir of an

Art Gallery, New York: Putnam, 1977)

Click to enlarge

Figure 24

Book cover of Tom Swift ;His

Giant Magnet (New York: Grosset;

Dunlap, 1932; cover illustration: Nat Falk)

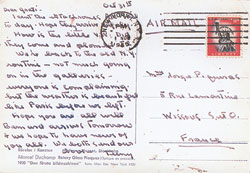

Robert Barnes: Yes, Levy was very much like Marcel. They were very close in character. We used to call him the “Jewish Marcel Duchamp.” But he was a remarkable person in his own right. I always thought that it was sad that Julian did not make art. In the end, he did make videos. There are several of them around. I did a painting, an imaginary portrait of Alfred Stieglitz in 1966(Fig. 23), that Julian liked and bought. It was reproduced in Julian’s book Memoir of an Art Gallery and it was such a surprise to see it in there again. It is not a bad painting I guess. I once also did a portrait of Julian from memory that his wife Jean thought very accurate. It showed him with his fly open, which Julian was prone to have. He was phenomenal. Actually I had quite a falling out with Julian because he wanted me to illustrateJacob Again, a book he wrote, a semi-science fiction thing. And the truth is that it wasn’t very good and I couldn’t illustrate it and I doodled around but Julian got impatient with me. I didn’t know what to say.

Tout-Fait: Talking about semi-science, you said there were teenage books that you and Duchamp shared a passion for.

Robert Barnes: Oh, yeah, no one knows about that, do they? Tom Swift and the Giant Magnet(Fig. 24). Tom Swift was a character, I don’t know who wrote them, but they were great children’s books(11).

Tout-Fait: So you were reading them at the time?

Robert Barnes: No, we both knew about them. I don’t know if they got translated into French or where he came across them. He probably found them in the Strand Bookstore or something.

Tout-Fait: How did you get to talk about that?

Robert Barnes: I don’t know how. Maybe I mentioned that some of his things were like the inventions of Tom Swift. Tom Swift was a great inventor, probably much better than Marcel. Some Duchamp scholar should read Tom Swift to see if there’s any correlation with anything.

Tout-Fait: When would Duchamp have first come across the Tom Swift books?

Robert Barnes: Well, I don’t know. Tom Swift books were popular in the ’30s and ’40s and probably even the ’50s.

Tout-Fait: Coming back to the surrealists you knew, Max Ernst was the earliest “acquaintance.” You said you ran away from home when you were 15, and you ran into him in Arizona where he resided with Dorothea Tanning between 1946 and 1953.

Robert Barnes:In Sedona. I didn’t know who the hell he was.

Tout-Fait: You were getting rid of his trash and then you bumped into him again when you were in New York.

Robert Barnes: Yeah. That’s a real odd coincidence because I worked with a friend and we would collect trash from rich people. And Max lived in Sedona then. I wonder what happened to that place. I’m sure his son Jimmy got it and Jimmy is dead now.

Tout-Fait: He was not rich really.

click to enlarge

Figure 25

Max Ernst,Capricorn,

1947(cast in 1964)

Robert Barnes: No, but we thought he was rich. We didn’t have anything. But we would go around to these homes in Sedona and offer to get rid of their garbage. And in places like that garbage is big business, you never get rid of it. And we offered to take it and dispose of it in a “clean and orderly fashion,” which meant we would dump it in any place we could where no one would see it. My friend had a pick-up truck – all Navahos if they have a vehicle, have turquoise pick-up. And we loaded it up with this plaster from this guy’s home, with faces on it, they were kind of interesting, and dumped them. So somewhere up there if you want to excavate, there’s a whole bunch of rejected Max Ernst sculpture. I have a picture of myself sitting on his “King and Queen”-sculpture (Fig. 25)(12).I looked like I was twelve.

Tout-Fait: While you were down there?

Robert Barnes: Yeah.

Tout-Fait: Who took the picture of you, your friend?

Robert Barnes: Yeah. Max Ernst was very shadowy. Whenever he stayed in New York, he stayed at Marcel’s.

Tout-Fait: What about Man Ray?

Robert Barnes: I didn’t like him.

Tout-Fait: You mentioned that Duchamp once introduced you to a dealer of ethnic art.

Robert Barnes: Yeah, Carlebach I think he was called.

Tout-Fait: Did he take you there?

Robert Barnes: The first time, I went with him. Carlebach was a dealer in ethnic material and he had this store filled, it was what you would expect a junk shop to have, filled from floor to ceiling with all of these ju-ju’s. You could buy an African sculpture for a couple hundred dollars or less.

Tout-Fait: So Duchamp brought you there because he liked the place?

Robert Barnes: Yes.

span class=”textbold”>Tout-Fait: Was there any literature that he recommended to you?

Robert Barnes: Oh yeah. Dujardin and Lautreamont, they all loved Lautreamont, but I’m not going to get into that. The book that was most like Marcel, I don’t know wether he loved it or not, was by A Rebours by Huysmans, Against the Grain. It was so like Marcel. That’s a story of art. Put too much on it and it’s going to die. Actually, Marcel introduced me to French literature, Camus, Celine, he was a bad boy. And of course I never liked Beckett. Beckett is the literary equivalent of Bergmann films, which at the time were very exciting, but if you saw them again, you would get very embarrassed (13).

click to enlarge

Figure 26

Marcel Duchamp, cover for

The Opposition and

Sister Squares Reconciled, 1932

Tout-Fait: So Duchamp introduced you to Beckett.

Robert Barnes: Yeah, he mentioned it and then I read it.

Tout-Fait: Beckett’s End Game might in part be based on Marcel’s chess game problem (14)

(Fig. 26). Do you play chess?

Robert Barnes: Yes, I hate it. I absolutely hate it. I played with Marcel because he liked to play with people who didn’t know how to play chess. You know, a chess champion is used to gambits and if he plays with someone who has no idea what they should be doing, it is almost more taxing. He liked that. I would put the pieces in positions that I thought were decorative. And of course I would surrender.

Tout-Fait: Did he teach you?

Robert Barnes: No, it was just a pastime. And what would happen would be that I would sacrifice so many pieces that it was very hard to get a checkmate. Everything is being sacrificed and it was just totally disorganized and I think that was something that Marcel liked.

Tout-Fait: There is this story that he got annoyed with John Cage (15)complaining that Cage never even tried to win. So there was also something where people were good chess players and he just didn’t think that they were trying hard enough to beat him.

Robert Barnes: That was a strange relationship. Didn’t Cage hate Etant Donnes?

Tout-Fait: I don’t know about that.

Robert Barnes: It was a weird relationship and I think egos went¡¦

Tout-Fait: But Cage owes a lot to Duchamp. It’s not the other way around. But now for something completely different: Paul Swan I’m supposed to ask you about. So who was Paul Swan?

Robert Barnes: God, if there was a Duchampian theater, it was Paul Swan. I did paintings with Paul Swan, I’ll show you one later, pastels. Paul Swan was an occupant of the apartments in the Carnegie Hall when the Carnegie Hall was great and real before it was fixed and made up for the deluxe world. In Carnegie Hall there were apartments and they were slowly getting rid of people who were in these apartments because they wanted them back either for space or for rich people. But Paul Swan held on. It was like, you know, what happened in New York with rent control.

Tout-Fait: How old was he?

Robert Barnes: I’ll tell you in a minute. He was very old. And in order to stay and pay the rent, Paul would have his soirees on Saturday evenings and you could go, he couldn’t charge because it was his apartment but there was a donation box. And he would dance and then he would give a little lecture. If you timed it right, you would get in on Paul’s bacchanal. And Marcel introduced me. Matta found Paul Swan, made Marcel go, and then he became a fan. And the best thing that he did was the bacchanal of the Sahara Desert in which he danced naked, virtually; he had veils, very gay. All by himself, he would do the bacchanal of the Sahara Desert losing his veils and ending up totally naked. Paul was in his late 80’s at this time and then he would stand in front of the audience stark naked and would explain the reason why his body was in such great condition and why his skin was so perfect was that he bathed daily in a vat of olive oil and that everyone should do that if they want to stay as young as he is. And he was one of the first health food addicts, he and Francis Stella, they were the first ones to be fanatical about health food. The trouble is, only Paul Swan thought that he still had smooth skin that looked really young. He was really a wreck. His little thingy was all shriveled. And of course everyone would throw money into the box afterwards because it was such a marvelous event.

Tout-Fait: So it wasn’t publicly advertised? Only artists went there basically? It was only known through word of mouth?

Robert Barnes: Yeah, basically. The thing is, he must have made a fortune because no one wanted Paul to get kicked out of Carnegie Hall. I don’t know what happened. I went to Europe after that and lost track but he probably died. Oh, those performances were so superb. It made the happenings seem mundane. You know, they think they started that stuff down at Judson Church. No! Swan’s soirees were a million times more exciting.

Tout-Fait: Every week?

Robert Barnes: I don’t know. I think every week.

Tout-Fait: How many people were there usually?

Robert Barnes: Twenty people. I know Matta always loved to go there and a whole group would go up there.

Tout-Fait: I have another question: You have a few works by Duchamp that he simply gave to you. That was very generous at the time. What did you think?

Robert Barnes: He gave something to me and he would always say, “Look, if you need money sometime, you could probably sell this.” We were thinking like a couple hundred dollars probably. I never sold them. I’ve had hard times. I’m sentimental.

Tout-Fait: It’s not about monetary value; it’s about this guy giving it to you.

Robert Barnes: I’m also not a “hem of the cloak” person.

click to enlarge

Figure 27

Robert Barnes,Belle

Haleine, ca. 1995

Tout-Fait: What’s that?

Robert Barnes: Touching Marcel’s hand to become empowered. You know, I did a painting about Marcel and I hate myself for it(Fig. 27).

Tout-Fait: I like it.

Robert Barnes: Well I don’t because I swore that I would never use Marcel in any way as a stepping-stone to anything.

Tout-Fait: Which a lot of people did who didn’t know him as well as you.

Robert Barnes: Yeah, well if you notice, the people that really did know Marcel, don’t like to talk about him. The fact that I’m doing this is really kind of weird. I shouldn’t be. And in some ways it is blasphemous. But there is nothing to blaspheme if you don’t turn Marcel into a God. Marcel was normal and very, very bourgeois. He was a normal guy, very normal. He smoked terrible cigars. He smoked “Blackstones” and he also smoked “La Frederic,” which is like smoking rope.

Tout-Fait: He never did any drugs?

Robert Barnes: No, why would he? Wine’s good enough, isn’t it?

Tout-Fait: Now, Duchamp¡¦

click to enlarge

Figure 28

Marcel Duchamp’s tombstone

at the Cimitiere Monumental

in Rouen, France

Robert Barnes: He’s dead now, you notice? What is it on his grave? It’s wonderful.

Tout-Fait: “Besides, it’s always the others that die” (Fig. 28). I like that too. We were talking before about how he gave you three or four works of his, and you didn’t ask him for, he didn’t want to get paid for…

Robert Barnes: Get paid?! Marcel never got paid anything.

Tout-Fait: ¡¦for the favors that you did for him or was it just because he felt a certain friendship towards you?

Robert Barnes: That’s what makes real friendship comfortable, when you don’t count favors. I’ve counted favors, all on his side. The guy was generous. Everyone knew that and I think that probably people did take advantage of him. I’m not sure that Schwarz didn’t.

Tout-Fait: And you didn’t run to him and want him to sign certain stuff.

Robert Barnes: Oh yeah, sign.

Tout-Fait: Well that’s good, because some people did.

Robert Barnes: “Oh, mister, can I have your autograph on my ball?”

Tout-Fait: And he probably wouldn’t have refused.

Robert Barnes: No he wouldn’t have.

Tout-Fait: You left New York when?

Robert Barnes: I’m not sure. I went to London to Slade School and had more contact with Matta and Copley, because Copley had a home over there. I had a great dinner once at Copley’s house. We ate off of Magritte plates with parts of the body painted on them and since we were guests of honor, my wife and I (my first wife) got first choice. She got the male plate and I got the female plate. Thought you might have hair in your food, kind of an interesting dinner. Matta always made things interesting.

Tout-Fait: And Matta you were the closest with, he introduced you to everyone and he was just one wild person.

Robert Barnes: Yeah he was a good painter too. You know, I’m not sure where Matta fits in, in the history. You know, who cares. What’s interesting is that we’re living in a generation of young people who are constantly preoccupied with their place in history. What the hell does it matter? Marcel never thought about that. Maybe later on when he started cataloguing stuff, he starting thinking that maybe he wanted to leave some legacy. But legacy is bullshit. But everyone now is “where’s my place in history.” How many times can you ask?

Tout-Fait: Well your generation will not decide who makes it into the history books.

Robert Barnes: No one will decide. Some lizard or something might decide in the final. But people are so worried about whether they are going to be known. Now they create money and become attached to it. I thank God I lived in the era of Marcel and those people, who weren’t. Money was certainly not much of a preoccupation. It drifted across their brains, but it was definitely not much of a preoccupation. It was interesting, I did a talk on de Kooning. (16)

While they were circulating that show of his and I got to the middle of the talk and I suddenly realized and said it out loud that I didn’t think anyone thought they were going to make money from their work, a lot of money, and it wasn’t until the ’70s that it started changing and people started clawing each other to get known, get a gallery, a good gallery, to get this and get that and the art is boring because of it. I mean how much can you be shocked by all the latest things? We have some guy cutting off pieces of his penis in a gallery, good for him.

Tout-Fait: Well it becomes shallow and hollow and everything has been done before and done better mostly.

Robert Barnes: I’m afraid Marcel unleashed some of that and I know he knew it and I think he was a little bit dismayed or amused; it would be both in this case.

Tout-Fait: Well that is what Apollinaire, who first wrote about him in 1913, said– that he was the artist who was going to reconcile people and art (17).The people and art come together and I think in a weird way he did.

Robert Barnes: And then you have to decide whether you want that. It sounds good but I’m not sure that’s what you want. I mean I’m really kind of intrigued by the bardic tradition as the artist being a mysterious power or medium. And in a lot of ways Marcel fit that very well. The Bards could intervene in worlds and stop them and create a poem that would solve everything. Not very realistic. There is something about art not being democratic that might be good. I certainly couldn’t justify it. But I’m functioning on instinct; maybe it’s not good that it’s available so much.

Tout-Fait: I think it is probably something that will change again. Maybe people will get into something else and then art is just there and will survive on its own, hibernating. Look at what is happening to poetry now. Not too many people read poetry. Poetry is really in a state of hibernation. And I mean you don’t really know. Two hundred years down the line poetry might be “the thing.” Everyone goes there and reads that as much as art is being looked at today. That very well might happen but we don’t know.

click to enlarge

Video 3

Interview with Robert Barnes

(Excerpt), January 2001.

Robert Barnes: I don’t object to what’s going on in contemporary art but I do think that it’s kind of boring. I also think that it is so closely meshed with fashion. That fashion brand having the show at the Guggenheim, what show was that?

Tout-Fait: The Armani Show at The Guggenheim, New York, between October 2000 and February 2001.

Robert Barnes: It is totally appropriate. Since it is hard to distinguish art from fashion anyhow. It is kind of interesting that always in the kind of painting that I did, people were denigrating the idea that art imitates life. What we have now is life imitating art and it’s recoiled on us a little bit, hasn’t it?

Tout-Fait: Now with your own art, what I’ve looked at and what I’ve seen in catalogues always seems to be in action, very much so.

Robert Barnes: Figure it out. I mean, what did you do today? We kept moving.

Tout-Fait: Futuristic approach.

Robert Barnes: Oh no, that’s what Marcel knew, transience, everything is in transit and you have to watch it and watch it evolve and transit. Going to a store and watching things move and turn into junk.

Tout-Fait: There are some historic figures that you refer to in your paintings.

Robert Barnes: There is Joyce, Tzara, Stieglitz (18).I really admired Tzara, he reminded me of myself when I was younger.

Tout-Fait: Did you meet him?

Robert Barnes: Once at a thing. It was way towards the end of his life, I think the last year of his life. I don’t remember when he died, in the ’60s. And he said that he thought the last bastion of an icon class was a conservative state.

Tout-Fait: And that’s where we are?

click to enlarge

Figure 29

George W.Bush, 43rd

President of the United States

Robert Barnes: No I don’t think that’s where we are, but I think that if you want something shocking anymore, it might have to be very conservative. Maybe that’s why we elected that guy with the tiny little (Fig. 29). Things flip back and forth. We’ve experienced so much license. I love license, I love not being under control. But we’ve experienced so much of it that it gets jaded. I mean, sex, sex is boring to kids. I always thought it was my daughters whom I should prohibit having sex and tell them that they can’t do this and it’s terrible so that they’d enjoy it. I thought holding hands was exciting when I was kid, now fucking is about that level, so where do you go up? Maybe killing people or something.

Tout-Fait: That’s true. There’s also a big movement of women who want to stay virgins until they get married.

Robert Barnes: Heh, try it.

Tout-Fait: You put yourself in a very interesting position of course where people will come knock on your door.

Robert Barnes: I have no objection to the drama and distance that people go through to get attention with their so-called works of art, except that they are getting known and I don’t like it. I don’t like getting known to art, particularly.

Tout-Fait: In a way, since there are no more movements…

Robert Barnes: Do you know what killed the movements? When someone decided to call the last movement that we heard of Neo-Geo. Even the yuppies laughed when you uttered that one, they did try Neo-romanticism after that. That was so pathetic.

Tout-Fait: Well because there is a lot of individuality going on, I think that in order to be an artist you also have to have social skills, to be a socializer, you know, schmoozing up to the right people and all to get exposure so that you will win a gallery show. Now it’s not in the hand of artists anymore. In a way it is tough to get back from there.

Robert Barnes: You know, Dada thought that they were anti-art. The social extremes of art is what really created an anti-art atmosphere and at a certain point it got exciting to see something that wasn’t trying to bop you. But I don’t know if we can go back to a state where we enter into something that is coming at us. And you know I always thought that the worst thing that happened – and I really didn’t discourage my children from it – was Sesame Street. Everyone raised their hands and said “Isn’t that wonderful, our children are learning the alphabet.” They are being shrieked at by purple animals and then at a certain point school started to entertain the students. I mean I ran into that in college. The best professors, the ones that are really given the awards, were the ones that were very eccentric, entertainers, and that’s nuts.

Tout-Fait: The entertainment thing is very American. That you have to entertain.

Robert Barnes: What it does is it closes you out of the act. It makes you victim of the act but it closes you out of the experience. All of your experience is sensation and you’re not allowed to move in. When I’m in Italy, I love to go see some of these Renaissance paintings that you can’t leave. You have to stay in those paintings; you can’t just say “look I’m shocked” and then go on. No, you look and you wonder.

Tout-Fait: That has already started with the reproduction of images in catalogues since the early 20th century. You are conditioned. You flip through them and you can look at all of this stuff very fast and no one is really strained, it is not demanded of you and you are not trained to appreciate art by looking at it for a very long time. Or by making that effort because you think that everything should be fast and then move on.

Robert Barnes: Well I’m not complaining. I think it’s good and that if it does destroy art as a thing, art as a possession or a commodity, then that is fine. We will start at another level and find something else.

Tout-Fait: Can you repeat the story about the turtle again that’s been sitting on your lap since the beginning of our interview?

Robert Barnes: There’s a guy in Michigan. I used to buy stuffed animals, taxidermy. He’s a master. I mean this turtle is beautiful, it even has mud on his back. It’s just a gorgeous piece of art, this thing. And he was a master, I mean I went up there and he was stuffing a polar bear.

Tout-Fait: You needed these for your art basically?

Robert Barnes: Yeah I like them around. My wife paints still-lives with them in it and I just like them to be here. Maybe it’s because they’re not supposed to be here. Well I would call him and he would sell me things that people would pay him a deposit to do and never come back for them. So I would pay the other part of the fee and they were cheap, like thirteen, fifteen dollars. So all of the sudden I tried calling and I could not get through and finally I checked up and called information and, I guess it can be told now, this guy tells me, “we had his phone tapped for a year.” Turns out he had been stuffing his animals with dope. A great way when you think of it. Who is going to suspect? If this turtle here is full of cocaine that would be very nice. I still don’t think I would open it up because it is too beautiful.

Tout-Fait: Is that the place where you got the pigskin?

Robert Barnes: No, no this was much later.

Tout-Fait: Do you remember the place where you got the pigskin?

Robert Barnes: I think it was in Trenton.

Tout-Fait: In Trenton, where he supposedly got the urinal.

Robert Barnes: Trenton’s a great place.

Tout-Fait: Was that a meat place?

Robert Barnes: A butcher. I didn’t know the urinal came from there. Trenton might be an art center. Did you ever think of that?

Tout-Fait: That was where the Trenton Pottery was, where Duchamp’s Mutt-urinal was supposedly made.

Robert Barnes: You see it’s an art center.

Tout-Fait: Why go to a butcher in Trenton if there are so many in New York?

Robert Barnes: Because no one would do it. Can you get pigskin off without wrecking it?

Tout-Fait: No, but that butcher could?

click to enlarge

Figure 30

Titian,The Flaying of

Marsyas, 1575-1576

Robert Barnes:I guess so. I live in this country village in Italy and the guy that butchers pigs every year asked me “Roberto, I want you to help me with the slaughter tomorrow.” And I said, “Vittorio, I’m a painter, not really a butcher.” And he said, “I have to get up at four in the morning. I want to be with someone who is a good conversationalist. I’ll show you how to kill pigs.” And he did. If you knew what was inside of pigs, you wouldn’t eat them. It was awful stuff. But it was interesting and that’s what got me started to do paintings about the Flaying of Marsyas (Fig. 30)(19),it means the removal of the external self in the Renaissance and I always liked the idea of peeling away layers. The painting came much later so I must have had the Duchampian idea on my mind of peeling away a skin and putting it somewhere else. People used to dress and masquerade in skins sometimes, not just furs, but sometimes other people’s skins. Anyway, the Italian butcher had me killing these pigs and it really is a shocking experience. Pigs are very human and it is very much like a human sacrifice. I did a lot of Flaying of Marsyas paintings after that. I never did a pig, but it is an act that you don’t forget.

Tout-Fait: You’re not happy with pop art?

Robert Barnes: Well why, I’m not unhappy either.

Tout-Fait: While we took our stroll through the Bloomington Art Museum you looked at certain paintings and said “Oh my God.”

Robert Barnes: Well I remember I had kids books “look at the spot” and then you’d look away and see a spot, so what? You know what we’ve done over the last hundred years? We have dissected the work of art. You have optical art, which is the visual, you have abstract expression, which was so involved with the touch, and I still love that. That’s probably why I don’t do other things because I love the feel of paint, very sensual, very sexual.

Tout-Fait: Touch is something you are never allowed to do in museums.

Robert Barnes: Museums are another story. They are mortuaries. You have abstract expression, which deals with surface, optical art, which is the effects of light and dark, of colors, you have pop art, which deals with subject matter. Basically the idea and sensation of the image left behind tactility and in some cases the optical effect of color. Duchamp represented the bigger idea of art as an idea or idea as the gas, motivated by the gas of the people, and that is probably the best of the bunch. If you keep dissecting, even conceptual art is just the idea. I always think that conceptual art grew out of the academic.

Tout-Fait: Conceptual art owes to Duchamp as well.

Robert Barnes: Yeah but see Duchamp appealed to the academics because he was an intellectual. Not that they ever understood it or ever would or could or should, but it was an intellectual act, so they had to distort it. The revenge, the way academics wreck art is by explaining it. It’s the most obscene thing you do. And look at the books on Marcel, thousands of books on Marcel, all of them falling over each other to explain. The best would be a book that is so absurd that it becomes another work, almost a readymade or some absurdity. But at any rate, I think that the conceptual art grew out of the academics, explaining so much that they finally did the ultimate thing, got rid of the act of art or work and had only the explanation of it. That’s fine, terrific, but I don’t like the pieces.

Tout-Fait: The only thing Duchamp wasn’t was political.

Robert Barnes: I never heard him say anything¡¦ political in what way?

Tout-Fait: Well, all of his known remarks on politics and world affairs probably do not exceed five hundred words.

Robert Barnes: Don’t you ever think that is the artist’s posture?

Tout-Fait: Well I would think that you would be a little bit more concerned about both world wars, nuclear bombs, and even the student riots in 1968.

click to enlarge

Figure 31

Pablo Picasso, Guernica, 1937

Robert Barnes: If you lookat it, Picasso (20)was very artificial in terms of his political acts, even the communist party was so inept that he didn’t like it.

Tout-Fait: Well Guernica (Fig. 31)was always¡¦

Robert Barnes: Well I’m not sure that that was even a factor, it didn’t certainly stop anything. Politics and art. Politics is always pathetic when it gets involved in art.

Tout-Fait: Well the other way around, you just talked about being the bard, being able to stop the war.

Robert Barnes: Well we can’t do that anymore. Walking onto the battlefield is a little easier than having missiles shot at you. I think that the political posture is almost designed for the artist. It’s pathetic. I like to shock people by saying that war is probably the ultimate work of art, so ultimate that, if you don’t do it well, you get killed. Artists are always talking about how hard it is to be an artist or make works or how painful¡¦ War is really horrible, painful, and if you do make a mistake, you don’t get a chance to erase it or wipe it off a canvas. I always think artists are such ninnies. I mean we can change everything and in a sense that is good but if you run over somebody on the street, you can’t back up and have them come back to life. In painting, if you make a mistake or everything goes wrong, you can wipe it off.

Tout-Fait: Because they’re suffering so much without actually experiencing¡¦

Robert Barnes: There’s no suffering involved in a work of art. But maybe realizing that you’re stupid is suffering.

Tout-Fait: So a lot more people are involved in the arts that probably should be doing something else.

Robert Barnes: Well 99% probably. That’s why they teach.

click to enlarge

Robert Barnes and his studio, Bloomington, January 2001

click images to enlarge

Robert Barnes,Oak (Duir), 2000

Notes

*Art Historian Herbert Molderings, with whom I have discussed this matter prior to the publication of this interview, expressed some doubt that–based on his recent research with specialists–the material used for the torso of Etant Donnes could actually be pigskin. (Only an examination of the material used for Given‘s torso, conducted by the Philadelphia Museum of Art, could once and for all clarify this matter). In a follow-up conversation with Robert Barnes (via phone on 1/14/2002), the artist, in addition to what he had said in the initial interview, recalled to have picked up the pigskin at a dock from a butcher dressed in a white apron. He picked up one big barrel, filled with water or brine which, upon delivery, was left at the base of the staircase leading up to Duchamp’s apartment since it was too heavy for both men to carry upstairs.

*Art Historian Herbert Molderings, with whom I have discussed this matter prior to the publication of this interview, expressed some doubt that–based on his recent research with specialists–the material used for the torso of Etant Donnes could actually be pigskin. (Only an examination of the material used for Given‘s torso, conducted by the Philadelphia Museum of Art, could once and for all clarify this matter). In a follow-up conversation with Robert Barnes (via phone on 1/14/2002), the artist, in addition to what he had said in the initial interview, recalled to have picked up the pigskin at a dock from a butcher dressed in a white apron. He picked up one big barrel, filled with water or brine which, upon delivery, was left at the base of the staircase leading up to Duchamp’s apartment since it was too heavy for both men to carry upstairs.

1.Chilean Surrealist painter Roberto Matta Echaurren (*1911) had met and admired Duchamp even before his arrival in New York in 1939. For more information on Matta and his relationship to Duchamp, see the introduction to this issue’s facsimile in the “Collection”-square, Rarity from 1944: A Facsimile of Duchamp’s Glass (by Katherine S. Dreier and Roberto Matta Echaurren)

1.Chilean Surrealist painter Roberto Matta Echaurren (*1911) had met and admired Duchamp even before his arrival in New York in 1939. For more information on Matta and his relationship to Duchamp, see the introduction to this issue’s facsimile in the “Collection”-square, Rarity from 1944: A Facsimile of Duchamp’s Glass (by Katherine S. Dreier and Roberto Matta Echaurren)

2. Between late 1951 and April 3, 1959, Duchamp (when in New York), lived in an apartment on 327 East 58th Street together with his wife Alexina “Teeny” Sattler whom he married on January 16, 1954. The fourth-floor walk-up was still rented by the German Surrealist painter Max Ernst (1891-1976) and his wife, the American Surrealist artist Dorothea Tanning (* 1910), both of whom moved to France in 1951.

2. Between late 1951 and April 3, 1959, Duchamp (when in New York), lived in an apartment on 327 East 58th Street together with his wife Alexina “Teeny” Sattler whom he married on January 16, 1954. The fourth-floor walk-up was still rented by the German Surrealist painter Max Ernst (1891-1976) and his wife, the American Surrealist artist Dorothea Tanning (* 1910), both of whom moved to France in 1951.

3.German-born avant-garde artist and filmmaker Hans Richter. The chess-game based story of 8×8, shot in the United States and featuring, among others, Jackie Matisse and Marcel Duchamp, includes a sequence showing the latter as the Black King.

3.German-born avant-garde artist and filmmaker Hans Richter. The chess-game based story of 8×8, shot in the United States and featuring, among others, Jackie Matisse and Marcel Duchamp, includes a sequence showing the latter as the Black King.

click to enlarge

click to enlarge  Balthus, (Untitled),1963

Balthus, (Untitled),1963

4. Long after the interview, it came to my attention that Virginie Monnier – in her “Catalog of Works” published in Jean Clair’s (ed.) Balthus exhibition catalogue for the late artist’s major retrospective at the Palazzo Grassi, Venice, 9 September 2001 – 6 January 2002 (Milan: Bompiani, 2001) – had described Courbet’s famous painting as incorrect. Comparing it to an untitled pencil drawing by Balthus from 1963 (a Courbet rasee, so to speak, though Balthus’ adolescent model might not have had any hair to speak of), which was obviously inspired by Courbet, Monnier writes: “[I]ndeed it reproduces an anatomical inaccuracy that in Courbet had caused outrage: the cleft of the vulva, as thin as a line, goes all the way to the crease of the anus, ignoring the anatomical particularities of the female body.” (p. 388)

5.Brazilian Surrealist sculptor Maria Martins (1894-1973); between ca. 1943-1948, Duchamp had an intense liaison with the wife of the Brazilian ambassador to the United States. For a detailed discussion of the early stages of Given‘s production, see the article Marcel Duchamp’s Window Display for Andre Breton’s Le Surrealisme et la Peinture, 1945 in the Articles-section of this issue of Tout-Fait.

5.Brazilian Surrealist sculptor Maria Martins (1894-1973); between ca. 1943-1948, Duchamp had an intense liaison with the wife of the Brazilian ambassador to the United States. For a detailed discussion of the early stages of Given‘s production, see the article Marcel Duchamp’s Window Display for Andre Breton’s Le Surrealisme et la Peinture, 1945 in the Articles-section of this issue of Tout-Fait.

6.Spanish Surrealist artist Joan Miro (1893-1983).

6.Spanish Surrealist artist Joan Miro (1893-1983).

7.Romanian-born Constantin Brancusi (1876-1957) was one of 20th century’s leading sculptors and a close friend of Duchamp’s from their early years in Paris. For some time, Duchamp became his representative, selling Brancusi’s sculptures, mostly to affluent American collectors.

7.Romanian-born Constantin Brancusi (1876-1957) was one of 20th century’s leading sculptors and a close friend of Duchamp’s from their early years in Paris. For some time, Duchamp became his representative, selling Brancusi’s sculptures, mostly to affluent American collectors.

8.Duchamp’s Locking Spoon (or Verrou de surete a la cuiller), a semi-readymade involving the door of his New York apartment in 1957, is based on a modified pun first printed in Francis Picabia’s 391 in July 1924.

8.Duchamp’s Locking Spoon (or Verrou de surete a la cuiller), a semi-readymade involving the door of his New York apartment in 1957, is based on a modified pun first printed in Francis Picabia’s 391 in July 1924.

9.The American artist, dealer and collector William Copley (1919-1996) met Duchamp in New York in the early 1940s and became an avid supporter and friend. His Cassandra Foundation purchased Etant Donnes and assured its transfer to the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

9.The American artist, dealer and collector William Copley (1919-1996) met Duchamp in New York in the early 1940s and became an avid supporter and friend. His Cassandra Foundation purchased Etant Donnes and assured its transfer to the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

10. American art dealer Julien Levy (1906-1981) was the first to sponsor a show on Surrealism and he is generally regarded as having played an essential role in the shift of the cultural avant-garde from Paris to New York. He and Duchamp oftentimes collaborated on various shows and projects.

10. American art dealer Julien Levy (1906-1981) was the first to sponsor a show on Surrealism and he is generally regarded as having played an essential role in the shift of the cultural avant-garde from Paris to New York. He and Duchamp oftentimes collaborated on various shows and projects.

11.Mostly written by Howard Garis under the pseudonym “Victor Appleton,” the highly popular juvenile literature series of Tom Swift’s adventures were published in 40 individual volumes by Grosset & Dunlap between 1910 – 1941. Every book featured a great abundance of scientific inventions. In the spirit of Jules Verne, Alfred Jarry and (to a lesser extent) Raymond Roussel, the books must certainly have held some charm for Duchamp.

11.Mostly written by Howard Garis under the pseudonym “Victor Appleton,” the highly popular juvenile literature series of Tom Swift’s adventures were published in 40 individual volumes by Grosset & Dunlap between 1910 – 1941. Every book featured a great abundance of scientific inventions. In the spirit of Jules Verne, Alfred Jarry and (to a lesser extent) Raymond Roussel, the books must certainly have held some charm for Duchamp.

12.According to Dorothea Tanning, Max Ernst’s sculpture Capricorn (Sedona, 1947) was first conceived as a garden sculpture “of regal but benign deities that consecrated our ‘garden’ and watched over its inhabitants.” (See: Dorothea Tanning, Birthday (San Francisco: Lapis, 1986) Ernst himself referred to the sculpture as a family portrait, depicting Dorothea, his two dogs and himself. It was cast in bronze and first turned into an edition in 1964.

12.According to Dorothea Tanning, Max Ernst’s sculpture Capricorn (Sedona, 1947) was first conceived as a garden sculpture “of regal but benign deities that consecrated our ‘garden’ and watched over its inhabitants.” (See: Dorothea Tanning, Birthday (San Francisco: Lapis, 1986) Ernst himself referred to the sculpture as a family portrait, depicting Dorothea, his two dogs and himself. It was cast in bronze and first turned into an edition in 1964.

13.French writer Edouard Dujardin’s (1868-1947) Les Lauriers sont coupees, 1888 (or The Laurels Have Been Cut), is often regarded to be the first novel introducing direct interior monologue; the writings of French author Isidore Ducasse (aka Comte de Lautreamont, 1846-1870) were held in high esteem by the Surrealists, who regarded his eccentric writing as a precursor to their own movement (especially his Les Chants de Maldoror, 1869); decadent French novelist and art critic Joris Karl Huysmans (1848-1907), A rebours, 1884; French existentialist writer Albert Camus (1913-1960); French novelist Louis Ferdinand Celine (1894-1961); Irish playwright and novelist Samuel Beckett (1906 -1989), End Game, 1957; Swedish film and theater director Ingmar Bergman (*1918)

13.French writer Edouard Dujardin’s (1868-1947) Les Lauriers sont coupees, 1888 (or The Laurels Have Been Cut), is often regarded to be the first novel introducing direct interior monologue; the writings of French author Isidore Ducasse (aka Comte de Lautreamont, 1846-1870) were held in high esteem by the Surrealists, who regarded his eccentric writing as a precursor to their own movement (especially his Les Chants de Maldoror, 1869); decadent French novelist and art critic Joris Karl Huysmans (1848-1907), A rebours, 1884; French existentialist writer Albert Camus (1913-1960); French novelist Louis Ferdinand Celine (1894-1961); Irish playwright and novelist Samuel Beckett (1906 -1989), End Game, 1957; Swedish film and theater director Ingmar Bergman (*1918)

14.In 1932, together with the chess master Vitaly Halberstadt, Marcel Duchamp co-wrote and designed a book on a highly specific endgame situation in chess, L’Oppostion et les cases conjuguees sont reconciliees (or Opposition and Sister Squares are Reconciled), published in French, German and English by L’Echiquir (Edmond Lancel): Brussels.

14.In 1932, together with the chess master Vitaly Halberstadt, Marcel Duchamp co-wrote and designed a book on a highly specific endgame situation in chess, L’Oppostion et les cases conjuguees sont reconciliees (or Opposition and Sister Squares are Reconciled), published in French, German and English by L’Echiquir (Edmond Lancel): Brussels.

15.American avant-garde musician John Cage (1912-1992) came under Duchamp’s spell soon after Cage arrived in New York in 1942.

15.American avant-garde musician John Cage (1912-1992) came under Duchamp’s spell soon after Cage arrived in New York in 1942.

16.Willem de Kooning (1904-1997). Born in Rotterdam, the action painter was one of the founding members of what came to be known as The New York School.

16.Willem de Kooning (1904-1997). Born in Rotterdam, the action painter was one of the founding members of what came to be known as The New York School.

17.French poet, art critic, writer and socialite Guillaume Apollinaire (1880-1918) was an early admirer of Duchamp. In his book of 1913, Les Peintres Cubistes, he made the statement that “[p]erhaps it will be the task of an artist as detached from aesthetic preoccupations and as intent on the energetic as Marcel Duchamp, to reconcile art and the people.