click to enlarge

Figure 1

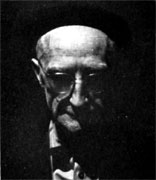

Photograph of Duchamp

taken by

Katherine

Dreier, Buenos Aires, 1918

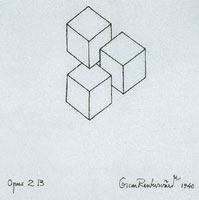

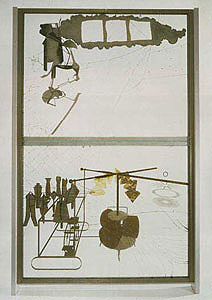

Figure 2

Man Ray, Photograph

of Duchamp in

his

hammock, date unknown

Chez Marcel Duchamp, la filière hispanophone passe d’une part par Buenos Aires, en Argentine, et le long séjour qu’il y fait en 1918-1919 (avec sa compagne Yvonne Chastel),(Figure 1) d’autre part par Cadaquès, en Espagne, et les séjours qu’il y fait en 1933 (avec sa compagne Mary Reynolds) puis de 1958 à 1968 (avec son épouse Alexina, dite Teeny).(Figure 2)

Bien qu’il n’y ait pas, pour cette filière, l’équivalent de ce qu’il y a pour les séjours de Duchamp dans l’Ouest des États-Unis en 1936, 1949 et 1963,ou de ce qu’il y a pour le long séjour, en Argentine justement, de l’écrivain polonais Witold Gombrowicz,

plusieurs analyses des oeuvres faites ou continuées durant ces séjours ainsi que plusieurs documents (correspondance, photographies, etc.) et témoignages relatifs à ces séjours ont été publiés.

Une bibliographie regroupant ces éléments, cependant, manque.

Mais voici, mettant en scène des gens peu connus, sinon pas connus des duchampiens, deux brefs témoignages inédits à propos des années 1960.

I.

Conversation sans guillemets avec Grati Baroni.

Grati Baroni et Jorge Piqueras, tous deux nés en 1925, ont quatre jeunes enfants lorsqu’ils rencontrent Teeny et Marcel Duchamp en 1960.

Cela s’est fait par le biais d’Emilio Rodríguez-Larraín, peintre péruvien, qui passait l’été à Llançà, près de Cadaquès, avec son ami Piqueras, peintre péruvien d’origine espagnole.

C’était en août, Francesca, notre dernier enfant (né le 10 juin), avait un peu moins de trois mois.

Pendant huit ans, jusqu’à la mort de Marcel, les Piqueras et les Duchamp se sont vus à Cadaquès, à Paris et à Wissous, près d’Orly, Wissous où ils habitent de 1961 à 1966. Presque tous les jours à Cadaquès (sauf en juillet-août 1968, où Grati est à Rome pour une question familiale), et plusieurs fois quand les Duchamp étaient en France: chez eux et chez les Lebel quelquefois.

Nous gardions la voiture des Duchamp pendant qu’ils étaient aux États-Unis et c’est nous, plusieurs fois, qui, avec ou sans Jacqueline Matisse, la fille de Teeny, allions chercher les Duchamp à Orly lorsqu’ils arrivaient de New York.

click to enlarge

![Faux-Vagin [

false Vagina]](/issues/volume2/issue_4/interviews/gervais/images/03_small.gif)

Figure 3

Marcel Duchamp,

Faux-Vagin [

false Vagina], 1962-63

![Faux-Vagin [false

Vagina]](/issues/volume2/issue_4/interviews/gervais/images/04_small.jpg)

Figure 4

Marcel Duchamp,

Faux-Vagin [false

Vagina],

1962-63, detail

C’est comme ça qu’un jour de 1962 ou de 1963, plutôt 1963 quand j’y repense, au retour de Cadaquès, a été “ fait ” Faux-Vagin: (Figure 3) lors d’un repas à Wissous, comme une “ joke ”, sans papier officiel et sans inscription du titre sur l’oeuvre. Juste une dédicace et une signature: “ pour Grati / affectueusement / Marcel ”. Et Teeny disant: “ Tiens, tu as un readymade! ”(Figure 4)

Vous ne pouvez pas imaginer les “ combines ”, les jeux de mots que Marcel faisait déjà avec la Volkswagen: “ Teeny est partie avec sa Faux-Vagin ”, par exemple

Nous l’accompagnions dans les petits villages autour de Cadaquès où il allait afin de participer à des tournois d’échecs importants et où il gagnait très souvent.

Cette amitié a été une amitié tranquille, non intéressée. En 1961, on se tutoyait déjà; les années suivantes, l’amitié sera plus grande encore.

***

Baroni est un nom italien. Je suis née à Florence: une Florentine ne peut pas être naïve, elle peut décider d’être bonne, mais elle ne peut pas être naïve! Grati est un prénom probablement inventé par mon parrain, un prénom qui a toujours été utilisé à mon sujet et qui est devenu mon vrai prénom. Et Grati Baroni de Piqueras (avec un de), c’est mon nom d’épouse. Depuis la séparation, je suis redevenue Grati Baroni, tout simplement.

J’ai vécu en Italie, au Pérou (1952-1956), puis en France. J’ai une formation en histoire de l’art, mais sans le diplôme. J’ai été peintre très jeune, à partir de l’âge de 14 ans, jusque dans les années cinquante et soixante, puis j’ai recommencé après une interruption.

Marcel, terriblement concerné par tout ce qui est art contemporain, parlait avec moi de la peinture de la Renaissance. Tout, en ce sens, l’intéressait. Et il était très éveillé sur la beauté physique. Il nous aimait, je pense, pour le couple que nous étions, que nous formions: un couple symbiotique, “ mythique ”. On était très beaux.

Et je me souviens qu’il m’a raconté qu’un jour, il a 40, 41 ans, il est à New York et très en amour, il est devant un trou profond dans une rue qu’on répare; il est soûl et, voyant ce trou, d’un seul coup il dessoûle, et pour toujours!

Marcel ayant été drôlement aidé (par Arensberg, Dreier, etc.), n’a-t-il pas voulu aider à son tour? Il a été très généreux pour Piqueras, par exemple, en lui présentant la galerie Staempfli. George et Emily Staempfli avaient une maison à Cadaquès. Je me souviens particulièrement d’un soir où les Dali, les Duchamp et nous, nous étions chez les Staempfli. Dali, le jour même sauf erreur, avait peint un petit tableau intitulé Le twist, une allusion à la danse qui faisait rage ces mois-là

En revanche, je n’ai jamais été au courant de la démarche de Marcel pour Piqueras auprès de Noma et Bill Copley faite début juin 1964 et qui n’a pas donné de résultats.

click to enlarge

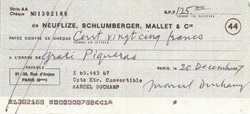

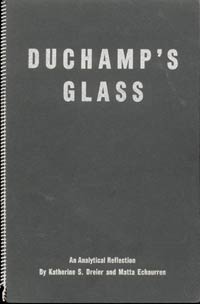

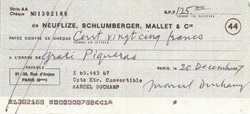

Figure 5

Check from Marcel

Duchamp to Grati Piqueras,

December 20, 1967,

collection G. Baroni, Paris

Marcel était très généreux dans la connaissance, dans les conseils. Chaque Noël, il envoyait un chèque aux enfants et ce, jusqu’à la fin. Le dernier chèque, ce qui aura été le dernier chèque, le 20 décembre 1967, on ne l’a pas touché. Marcel était très généreux dans la connaissance, dans les conseils. Chaque Noël, il envoyait un chèque aux enfants et ce, jusqu’à la fin. Le dernier chèque, ce qui aura été le dernier chèque, le 20 décembre 1967, on ne l’a pas touché. ((Figure 5)

J’étais à Cadaquès le jour où Marcel a fait ce qui s’intitulera Medallic Sculpture. Cela s’est passé, si mes souvenirs sont bons, la même année que Man Ray est venu à Cadaquès voir Marcel. Dans son Autoportrait, il parle de ce séjour de 1961. Il s’agissait pour Marcel de trouver le moyen de “ boucher ” le bain-douche de son petit appartement: plutôt Bouche-douche, en effet, que Bouche-évier. (Figure

6) Il a d’abord fait un modèle en plâtre, puis en plomb, et cela est resté un objet utilitaire pendant plusieurs années, en fait jusqu’à ce qu’il consente à autoriser la International Collectors Society de New York à en faire un objet d’art en 1967.

click images to enlarge

- Figure 6 (recto)

- Figure 6 (verso)

- Marcel Duchamp, Bouche-évier

[ Sink Stopper],1964, Collection

Rhonda Roland Shearer

- Marcel Duchamp, Bouche-évier

[ Sink Stopper],

1964, Collction Rhonda Roland Shearer

Cette année-là, Man Ray et Marcel s’étaient fait un téléphone avec des boîtes de conserves vides et une corde, afin de se parler–comme des enfants–depuis leur tour louée!

C’est à Paris en 1962, si je me souviens bien, que nous avons présenté Marcel à Gianfranco Baruchello, le peintre italien, lequel les invitera en Italie plusieurs fois par la suite. Et ce dernier connaissait Arturo Schwarz qui travaillait déjà sur Duchamp.En Europe, l’activité artistique de Duchamp, à cette époque en tout cas, n’était pas si connue.

Et nous avons présenté Baruchello au critique d’art Alain Jouffroy, déjà venu à Wissous dîner chez nous avec Marcel; Jouffroy écrira et sur Baruchello et sur Piqueras.

click to enlarge

Figure 7

Marcel Duchamp, Aimer

tes héros [Love

Your Heros], 1963

C’est aussi à Paris, en 1962 je crois, que nous avons présenté Marcel à Bruno Alfieri, directeur de la revue mETRO et parrain de notre fille Francesca. On connaît la suite: le petit dessin intitulé M.É.T.R.O. (1963). (Figure

7)

C’est à Cadaquès en août 1962, par Marcel, que j’ai connu sa soeur Suzanne. J’ai sympathisé beaucoup avec elle. Elle m’a raconté bien des choses sur lui, entre autres que, lorsqu’ils étaient des enfants et des adolescents, ils avaient une complicité, une communion incroyable: elle pensait à une chose et il la concrétisait, et vice-versa, ils étaient à l’unisson.

Le 30 septembre 1968, deux jours avant sa mort: “ C’est vous, je veux vous voir seuls ”. Un message d’une affection énorme. Nous sommes allés dîner chez lui, à Neuilly.

Après sa mort, la relation s’est à peu près estompée. Notre rupture, Jorge et moi, a lieu en 1969, notre séparation en 1973. C’est bien plus tard, par notre fils Lorenzo, qu’a été repris le fil de l’amitié avec Teeny et Jacqueline qui ont beaucoup apprécié cette exposition, intitulées L’époque, la mode, la morale, la passion, à laquelle il a travaillé comme architecte.

C’est après l’exposition Paris-New York,où j’avais prêté une oeuvre de Suzanne Duchamp que j’aimais beaucoup, qu’Étienne-Alain Hubert est venu chez moi et a “ découvert ” la targue (Faux-Vagin), une chose privée, intime. On ne découvre pas une oeuvre chez moi. Elle sera exposée pour la première fois dans un musée au Japon en août-septembre 1981 et reproduite pour la première fois, bien qu’en noir & blanc, dans le catalogue de cette exposition.

Quand j’ai dû vendre ce readymade, et cela me faisait de la peine de le vendre à quelqu’un qui n’aurait pas aimé Marcel comme nous, j’ai contacté Bill Copley en premier, mais il n’était pas intéressé. J’ai aussi essayé avec Jasper Johns, mais cela ne l’intéressait pas non plus. Alors il a disparu dans le marché de l’Art! Dommage… Je donnerais aujourd’hui n’importe quoi pour l’avoir encore.

***

J’ai connu beaucoup d’artistes (Fernand Léger, Constantin Brancusi, Henri Cartier-Bresson, etc.), mais suis restée volontairement en retrait.

J’ai un respect total pour l’autre: ce qu’il est (sa personne), ce qu’il fait (son oeuvre).

Je n’ai rien – rien conservé, rien thésaurisé – et je ne veux rien. Je ne voulais pas prendre ce que mes amis italiens – Giacometti, Magnelli, Fontana – me suggéraient de choisir. Ce qui reste de nos rapports, de mes rapports avec les Duchamp? C’est peut-être Rodríguez-Larraín qui pourrait avoir conservé des documents comme des lettres ou des photos de vacances avec nous.

Toutefois, je regrette de n’avoir pas tenu de journal, même minimal, à cette époque. Les vrais amis ne calculent pas!

Je vivais intensément toutes nos relations qui étaient exceptionnelles, de qualité, et qui me suffisaient. Avec ma famille, c’est la même chose: j’ai très peu de photos.

***

Annexe

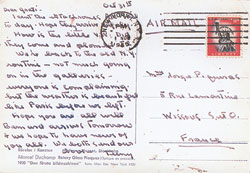

Carte postale de Teeny (New York, 31 octobre 1965) à Grati: (Figure 8)

click images to enlarge

- Figure 8 (recto)

- Figure 8 (verso)

Mme Jorge Piqueras 5 Rue Lamartine

Wissous S. et. O. [Seine-et-Oise] France

Oct. 31st

Dear Grati –

I sent the ektachromes Air Mail today – Hope they arrive safely

–

How is the little V.W.? Did they come and plombé it [?]

We’re back to the old N.Y. routine – not much going on in the galleries – everyone is complaining, but the weather is beautiful like Paris before we left.

Hope you are all well. Bernard

arrives tomorrow & we hope to have news of you all. We both send our love –

Teeny

[31 oct.

Chère Grati –

J’ai envoyé aujourd’hui par avion les ektachromes – J’espère qu’ils arriveront à bon port

–

Comment va la petite Volkswagen? Sont-ils venus et l’ont-ils plombée?

Nous sommes revenus à la vieille routine newyorkaise – pas beaucoup de sorties dans les galeries – tout le monde se plaint, mais la température est belle comme à Paris avant que nous quittions.

J’espère que vous êtes tous bien. Bernard arrive demain et nous espérons avoir des nouvelles de vous tous. Amitiés de nous deux –

Teeny

II.

Cinq questions à Emilio Rodríguez-Larraín

Quelles sont les grandes lignes de votre curriculum vitae?

Je suis né à Lima en 1928. Ma première exposition individuelle remonte à 1950, ma première exposition collective à 1951.

À l’époque de ma rencontre avec Marcel Duchamp, j’ai des expositions individuelles à Milan (1959, 1960, 1961 et 1963), Cologne (1960), Francfort (1960), Berlin (1960), New York (1962 et 1965, à la Staempfli Gallery; 1967, à la Rose Fried Gallery), Washington (1963), Bruxelles (1965), etc.

J’ai reçu en 1965 le prix de la William and Noma Copley Foundation; Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, Max Ernst, Roberto Matta et Walter Hopps, entre autres, étaient du jury.

Comment avez-vous été amené à rencontrer Marcel Duchamp? Où, quand et comment cela s’est-il passé?

J’ai connu Marcel Duchamp par Gordon Washburn, directeur du Carnegie Institute de New York. Il était venu à Milan m’inviter à une exposition au Carnegie Institute. Nous sommes devenus très copains avec lui et sa famille. Il m’a demandé où nous passions nos vacances, et ils sont venus se joindre à nous à Llançà, sur la Costa Brava. Une fois là, il a réalisé que nous étions tout près de Cadaquès, lieu de séjour de Marcel Duchamp, de Salvador Dali, de Man Ray et d’autres.

Nous y sommes allés et il m’a fait connaître tous ces grands artistes.

Où aviez-vous coutume de le retrouver?

Avec Marcel Duchamp a commencé tout de suite une grande amitié. Il venait à Llançà, nous allions à Cadaquès, nous nous sommes retrouvés à Paris, à Neuilly, à New York.

Quels étaient vos rapports avec lui et avec Teeny?

Vie quotidienne avec Marcel Duchamp et Teeny, donc art, échecs, langage, promenades, toros, autant à Paris qu’à New York ou sur la Costa Brava.

Qu’aura été Duchamp pour vous, finalement?

Un grand ami, autant lui que sa femme, et un artiste que j’ai respecté et respecte encore beaucoup, le trouvant l’homme le plus lucide que j’aie connu, généreux, courageux.

Documents joints:

click to enlarge

Figure 9

Marcel Duchamp, Self-

Portrait in

Profile, 1958

click to enlarge

Figure 10

Emilio Rodrígue

z-Larraín, 1965

Figure 11

Emilio Rodríguez

-Larraín, 1965

• Dédicace du livre de Robert Lebel, Sur Marcel Duchamp (1959), à M. et Mme Piqueras, 1960 selon toute vraisemblance. (Coll. G. Baroni, Paris.(Figure

9)

• Deux photos d’Emilio Rodríguez-Larraín au vernissage de Not Seen and/or Less Seen of/by Marcel Duchamp/Rrose Sélavy, 1904-1964, New York, Cordier & Ekstrom, 13 janvier 1965. À sa droite sur une photo: George Staempfli; derrière son coude droit sur une autre photo: Marcel Duchamp! (Coll. E. Rodríguez-Larraín, Lima.) (Figure

10 & 11)

• Carte postale de Teeny Duchamp à Mme Jorge Piqueras, 31 octobre 1965. (Coll. G. Baroni, Paris.)

• Chèque de Marcel Duchamp à Grati Piqueras, 20 décembre 1967. (Coll. G. Baroni, Paris.)

• Deux photos d’un mur du bar Meliton, Cadaquès. (Coll. André Valois, Montréal, 1994.)

Autour d’une plaque qui se lit “ AQUI JUGAVA ALS / ESCACS L’INOBLIDABLE / MARCEL DUCHAMP [ici jouait aux / échecs l’inoubliable / Marcel Duchamp] ”, des artefacts rappellent la présence de l’homme: deux photos, une lettre (à propos d’une rencontre chez Meliton), la reproduction d’une toile de Jacques Villon le représentant vers 1951, et un miroir dans lequel est décomposé, entre “ ciel ” et “ champ ”, le nom du bar (“ me / mel / elit / lito / liton ”, etc].

(Figure 12 & 13)

click images to enlarge

- Figure 12

The wall at the

bar Meliton,

Cadaqués

- Figure 13

The wall at the bar Meliton,

Cadaqués

Notes

1. Bonnie Clearwater (sous la dir. de), West Coast Duchamp, Miami Beach, Grassfield Press, 1991, 128 p.

2. Voir Rita Gombrowicz, Gombrowicz en Argentine. Témoignages et documents, 1939-1963, Paris, Denoël, 1984, 295 p.

2. Voir Rita Gombrowicz, Gombrowicz en Argentine. Témoignages et documents, 1939-1963, Paris, Denoël, 1984, 295 p.

3.Exemples d’oeuvres faites durant ces séjours: À regarder (l’autre côté du verre) d’un oeil, de près, pendant presque une heure (1918), Readymade malheureux (1919), With my tongue in my cheek (1959), Torture-morte (1959), Sculpture-morte (1959).

3.Exemples d’oeuvres faites durant ces séjours: À regarder (l’autre côté du verre) d’un oeil, de près, pendant presque une heure (1918), Readymade malheureux (1919), With my tongue in my cheek (1959), Torture-morte (1959), Sculpture-morte (1959).

4.Rédigée à partir de notes prises lors d’un téléphone de Grati Baroni (19 juillet 1998), d’une part, d’une longue conversation chez elle (4 juin 1999), d’autre part, puis revue par elle le 29 juin 1999 et légèrement augmentée le 20 juillet 1999.

4.Rédigée à partir de notes prises lors d’un téléphone de Grati Baroni (19 juillet 1998), d’une part, d’une longue conversation chez elle (4 juin 1999), d’autre part, puis revue par elle le 29 juin 1999 et légèrement augmentée le 20 juillet 1999.

5. En 1960, les Duchamp sont à Cadaquès du 1er juillet au 1er septembre.

5. En 1960, les Duchamp sont à Cadaquès du 1er juillet au 1er septembre.

6. Entre le 19 septembre et le 1er octobre 1963, donc, quelques jours avant Signed sign (Pasadena, 7 octobre 1963).

6. Entre le 19 septembre et le 1er octobre 1963, donc, quelques jours avant Signed sign (Pasadena, 7 octobre 1963).

7.La graphie du titre sera donc celle de Duchamp lui-même dans une lettre à Arne Ekstrom (Cadaquès, 3 septembre 1966), et ce bien qu’il parle de son automobile: “ Nous rentrons à Neu-Neu le 21 sept. par Volkswagen (Faux-Vagin) et N.Y. vers le 15 oct. par avion. ” Neu-Neu, c’est-à-dire Neuilly, en banlieue ouest de Paris.

7.La graphie du titre sera donc celle de Duchamp lui-même dans une lettre à Arne Ekstrom (Cadaquès, 3 septembre 1966), et ce bien qu’il parle de son automobile: “ Nous rentrons à Neu-Neu le 21 sept. par Volkswagen (Faux-Vagin) et N.Y. vers le 15 oct. par avion. ” Neu-Neu, c’est-à-dire Neuilly, en banlieue ouest de Paris.

8.Voir aussi, dans la carte postale de Teeny à Grati en 1965 reproduite en annexe, ce qui concerne la V.W.

8.Voir aussi, dans la carte postale de Teeny à Grati en 1965 reproduite en annexe, ce qui concerne la V.W.

9.Ce séjour a plutôt lieu lorsqu’il a 39 ans: du 20 octobre 1926 au 26 février 1927, en effet, il est aux États-Unis afin d’organiser deux expositions Brancusi, l’une à la Joseph Brummer Gallery, New York, 17 novembre-15 décembre 1926, l’autre à l’Arts Club of Chicago, 4-22 janvier 1927. Cette femme pourrait bien être Alice Roullier, de l’Arts Club.

9.Ce séjour a plutôt lieu lorsqu’il a 39 ans: du 20 octobre 1926 au 26 février 1927, en effet, il est aux États-Unis afin d’organiser deux expositions Brancusi, l’une à la Joseph Brummer Gallery, New York, 17 novembre-15 décembre 1926, l’autre à l’Arts Club of Chicago, 4-22 janvier 1927. Cette femme pourrait bien être Alice Roullier, de l’Arts Club.

Click to enlarge

click to enlarge

Figure 9

Salvardo Dali,

Twist dans l’atelier

de Vélasquez, 1962

10. En 1962, selon toute vraisemblance, la première version de Twist dans l’atelier de Vélasquez, huile sur toile (mais s’agit-il de cette oeuvre?), est de cette année-là. Quant aux chansons à succès, elles sont essentiellement de 1961-1962: The twist et Let’s twist again (interprétées par Chubby Checker), Twist and shout (par the Isley Brothers) et Twistin’ the night away (par Sam Cooke).

10. En 1962, selon toute vraisemblance, la première version de Twist dans l’atelier de Vélasquez, huile sur toile (mais s’agit-il de cette oeuvre?), est de cette année-là. Quant aux chansons à succès, elles sont essentiellement de 1961-1962: The twist et Let’s twist again (interprétées par Chubby Checker), Twist and shout (par the Isley Brothers) et Twistin’ the night away (par Sam Cooke).

11. Voir Marcel Duchamp in 20 photographs by Gianfranco Baruchello, avant-propos de Piero Berengo Gardin, Rome, Edizioni Gregory Fotografia, 1978; photos prises entre 1962 et 1966 en Italie (à Rome, à Bomarzo, à Cerveteri et en Ombrie), en Espagne (à Cadaquès) et aux États-Unis (au Philadelphia Museum of Art).

11. Voir Marcel Duchamp in 20 photographs by Gianfranco Baruchello, avant-propos de Piero Berengo Gardin, Rome, Edizioni Gregory Fotografia, 1978; photos prises entre 1962 et 1966 en Italie (à Rome, à Bomarzo, à Cerveteri et en Ombrie), en Espagne (à Cadaquès) et aux États-Unis (au Philadelphia Museum of Art).

12. Arturo Schwarz commence à travailler sur l’oeuvre de Duchamp en 1957.

12. Arturo Schwarz commence à travailler sur l’oeuvre de Duchamp en 1957.

13. Alain Jouffroy, “ Piqueras chez Eiffel ”, XXe siècle, Paris, nouvelle série, n° 48, juin 1977; “ Baruchello, navigateur en solitaire ”, n° 50, juin 1978).

13. Alain Jouffroy, “ Piqueras chez Eiffel ”, XXe siècle, Paris, nouvelle série, n° 48, juin 1977; “ Baruchello, navigateur en solitaire ”, n° 50, juin 1978).

14.Bernard Blistène, Catherine David et Alfred Pacquement (sous la dir. de), L’époque, la mode, la morale, la passion. Aspects de l’art aujourd’hui, 1977-1987, Centre d’art et de culture Georges Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, 21 mai-17 août 1987; Katia Lafitte et Lorenzo Piqueras, assistés de Diane Chollet, en sont les architectes. Voir par ailleurs Roselyne Marsaud Perrodin, “ Qualifier l’espace. Entretien avec Lorenzo Piqueras ”, Pratiques, Rennes, n° 2, automne 1986, p. 117-139.

14.Bernard Blistène, Catherine David et Alfred Pacquement (sous la dir. de), L’époque, la mode, la morale, la passion. Aspects de l’art aujourd’hui, 1977-1987, Centre d’art et de culture Georges Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, 21 mai-17 août 1987; Katia Lafitte et Lorenzo Piqueras, assistés de Diane Chollet, en sont les architectes. Voir par ailleurs Roselyne Marsaud Perrodin, “ Qualifier l’espace. Entretien avec Lorenzo Piqueras ”, Pratiques, Rennes, n° 2, automne 1986, p. 117-139.

15.Centre d’art et de culture Georges Pompidou, 1er juin-19 septembre 1977. Cette exposition a lieu immédiatement après l’exposition Duchamp (Marcel Duchamp, 31 janvier-2 mai 1977), exposition inaugurale.p>

15.Centre d’art et de culture Georges Pompidou, 1er juin-19 septembre 1977. Cette exposition a lieu immédiatement après l’exposition Duchamp (Marcel Duchamp, 31 janvier-2 mai 1977), exposition inaugurale.p>

16.Ce dernier m’écrit (Lima, 24 août 2000): “ Toutes les photos et tous les documents que j’avais concernant mes rapports avec Marcel Duchamp (dont une rasée L.H.O.O.Q., invitation à un vernissage chez Cordier & Ekstrom) m’ont été volés à Miami lorsque j’y vivais il y a quelques années.”

16.Ce dernier m’écrit (Lima, 24 août 2000): “ Toutes les photos et tous les documents que j’avais concernant mes rapports avec Marcel Duchamp (dont une rasée L.H.O.O.Q., invitation à un vernissage chez Cordier & Ekstrom) m’ont été volés à Miami lorsque j’y vivais il y a quelques années.”

17.Jacqueline Matisse, dans deux télécopies (27 avril 2001), précise le contexte: “ Marcel and Teeny’s VW bug was parked unused at the Piqueras’ in Wissous over the winter. In order to pay less tax on the car, the customs authorities required a lead seal on the vehicle when not in use. That is what Teeny is inquiring about in her card. […] Teeny used her best “franglais”… when talking about this car […]. ” [La coccinelle de Marcel et Teeny était stationnée chez les Piqueras à Wissous durant l’hiver lorsqu’elle n’était pas utilisée. Afin de payer une taxe moindre sur cette automobile, les autorités douanières exigeaient qu’un sceau de plomb soit apposé sur le véhicule. Voilà ce que demande Teeny dans la carte. […] Elle utilise son meilleur “ franglais ”… en parlant de l’aut […].”

17.Jacqueline Matisse, dans deux télécopies (27 avril 2001), précise le contexte: “ Marcel and Teeny’s VW bug was parked unused at the Piqueras’ in Wissous over the winter. In order to pay less tax on the car, the customs authorities required a lead seal on the vehicle when not in use. That is what Teeny is inquiring about in her card. […] Teeny used her best “franglais”… when talking about this car […]. ” [La coccinelle de Marcel et Teeny était stationnée chez les Piqueras à Wissous durant l’hiver lorsqu’elle n’était pas utilisée. Afin de payer une taxe moindre sur cette automobile, les autorités douanières exigeaient qu’un sceau de plomb soit apposé sur le véhicule. Voilà ce que demande Teeny dans la carte. […] Elle utilise son meilleur “ franglais ”… en parlant de l’aut […].”

18.Bernard Monnier, mari de Jacqueline Matisse.

18.Bernard Monnier, mari de Jacqueline Matisse.

19. Lima, 24 août 2000, en réponse à des questions écrites d’André Gervais envoyées le 21 juillet.

19. Lima, 24 août 2000, en réponse à des questions écrites d’André Gervais envoyées le 21 juillet.

20. La Pittsburgh Triennial se tiendra en 1961 au Carnegie Institute.

20. La Pittsburgh Triennial se tiendra en 1961 au Carnegie Institute.

21. Sur ce haut lieu de Cadaquès, voir Henri-François Rey,

21. Sur ce haut lieu de Cadaquès, voir Henri-François Rey,

Le café Meliton, Paris, Balland, 1987).

Figs. 3, 4, 6-8

©2002 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

All rights reserved.

Figure 1Thomas Hirschhorn,

Figure 1Thomas Hirschhorn, Figure 2Thomas Hirschhorn,

Figure 2Thomas Hirschhorn, Figure 3Thomas Hirschhorn,

Figure 3Thomas Hirschhorn, Figure 4Thomas Hirschhorn,

Figure 4Thomas Hirschhorn, Figure 5Thomas

Figure 5Thomas Figure 6Thomas

Figure 6Thomas

![Faux-Vagin [

false Vagina]](/issues/volume2/issue_4/interviews/gervais/images/03_small.gif)

![Faux-Vagin [false

Vagina]](/issues/volume2/issue_4/interviews/gervais/images/04_small.jpg)