click to enlarge

Figure 1

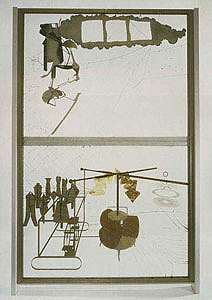

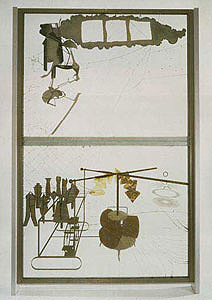

Marcel Duchamp, Three Standard Stoppages, 1913

Marcel Duchamp’s readymade, but “not quite,” as he called the Three Standard Stoppages(Fig. 1), is a highly ramified work of art.(1)The pieces of string used in its construction are related to sight lines and to vanishing points. In addition to their ostensive references to perspective and projective geometry, the Stoppages allude to happenstance. They are perhaps the artist’s best known work that incorporates uncertain outcomes into its operation. (In one of his Green Box notes, Duchamp says that the Stoppages are “canned chance.”)(2) To make the work, he glued three pieces of string to three narrow canvases painted solid Prussian blue. (Each string had a different randomly generated curvature.) He then cut three wooden templates to match the shapes of these “diminished meters.”(3)

click still images to enlarge

Figure 2

Marcel Duchamp, Network of Stoppages, 1914

Figure 3

Marcel Duchamp, Bride Stripped Bare

by Her Bachelors, Even, 1915-23

As this description indicates, the piece was quite unusual physically, and it was conceptually unprecedented. In terms of his personal development, Duchamp said the work had been crucial: “… it opened the way–the way to escape from those traditional methods of expression long associated with art. …For me the Three Standard Stoppages was a first gesture liberating me from the past.”(4)

Duchamp used the Stoppages to design the pattern of lines in his painting Network of Stoppages (Fig. 2) and then, after rendering this plan view in perspective, transferred it to The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (Fig. 3). In the Large Glass, as the Bride Stripped Bare . . . is also known, the “network” comprises the “capillary tubes,” iconographical elements that connect the “nine malic molds.”(5) The Three Standard Stoppages, the Network of Stoppages, and the Large Glass are associated with one another through geometrical projection and section. Duchamp’s approach, with respect to establishing their mutual relationships, is complex. He not only redrew the Network

of Stoppages in perspective so that he could incorporate the scheme into the imagery of the Glass, he also recast physical counterparts of the Stoppages into the actual structure of the Glass: the

three plates used in the Three Standard Stoppages are conceptually related to the three narrow sections of glass used to construct the “garments” of the Bride (Fig. 4). In each work, two plates

are in green glass, and one is in white glass.(6) The strips of glass at the horizon line of the Large Glass are seen edge-on, an arrangement comparable to looking down into the box of the Three

Standard Stoppages with the sheets of glass inserted into their slots. To my knowledge, this relationship was first pointed out by Ulf Linde:

The Bride’s Clothes are to be found on the horizon–the line that governs the Bachelor Apparatus’ perspective and which is in the far distance. Thus, the Clothes seem to be the source of the waterfall. Moreover, the Clothes are undoubtedly the hiding-place

of the Standard Stoppages, as well. For this part, as it is executed on the Glass, looks exactly like the glass plates as they appear set in the croquet case–as if the Clothes simply repeated the three glass plates in profile. One might say that it is the three threads that set the Chariot in motion.(7)

click still images to enlarge

Figure 4

Marcel Duchamp, Bride Stripped

Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (Detail:The “garments”

of the Bride), 1915-23

Figure 5

Marcel Duchamp,Chocolate

Grinder, No. 2, 1914

Although some of what Linde says here is unclear, at least to me, it is nonetheless suggestive, especially his proposition that the Stoppages are hidden in the Bride’s clothing. Duchamp’s use of different colored glass in just the same way in both applications (and the colors are more apparent when the glass plates are seen edge-on) indicates that he somehow meant for the Stoppages and the Bride’s “garments” to be linked together. I believe that their most important affiliation is perspectival: the vanishing point at the horizon line of the Glass is tied to the “garments” through geometry.

In a note from the Box of 1914 that was subsequently republished in the Green Box, Duchamp explains that pieces of string one meter long were to be dropped from a height of one meter, twisting “as they pleased” during their fall. The chance-generated curvatures would create “new

configurations of the unit of length.”(8) Although we do not know exactly how he constructed the work, we do know that he almost certainly did not use this method. The ends of the pieces of string in the Stoppages are sewn through the surfaces of the canvases and are attached to them from behind.(9) Presumably, Duchamp sewed down the strings, leaving them somewhat loose, jiggled and jostled them back and forth until he obtained three interesting curves, and then glued the segments to the canvases using varnish. Sewing would not have been out of keeping with his general working methods, especially since he was also at this time (1914) sewing thread to his painting Chocolate Grinder, No. 2 (Fig. 5)

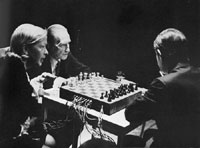

Duchamp wanted to relate his various works to each other. The moving segments of thread in the Three Standard Stoppages are conceptually similar to the moving lines and shapes in his cubo-futurist paintings. They are also conceptually similar to the parallel lines on the drums of the “chocolate grinder,” which can, in their turn, also be related to the chronophotographic sources of the earlier paintings. Chronophotography was among Duchamp’s primary interests during this period.(10) What I have in mind here can be seen by comparing Duchamp’s works with Étienne-Jules Marey’s images of moving lines Figs. 6 and 7). These kinds of time-exposure photographs not only recall such paintings as Sad Young Man on a Train (Fig. 8) and Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (Fig. 9), but also the Three Standard Stoppages and Chocolate Grinder, No. 2.(11)

click images to enlarge

- Figure 6

Étienne-Jules

Marey, Image of moving lines - Figure 7

Étienne-Jules

Marey, Image of moving lines - Figure 8

Marcel Duchamp,

Sad Young Man

on a Train, 1911

####PAGES####

In addition to implying something being stopped, the word “stoppage” also suggests something being mended or repaired. In French, “stoppage” refers to sewing or reweaving a tear in a fabric in such a way that the tear can no longer be seen.(12) From this perspective, the individual lines in the sculpture and the network of lines in the painting can be compared with the breaks in the Large Glass. In his early monograph, Robert Lebel pointed out that the Network of Stoppages bears a strange resemblance to the pattern of fissures in the Glass, as if the painting had somehow been a preliminary study for the subsequent breakage.(13) When Duchamp put the Glass back together, or perhaps we could also say when he “rewove” it, he no doubt also noticed the fortuitous similarities. The shapes of the line segments generated by the pieces of thread were random, but they seemed planned. Likewise, the line segments caused by the Glass being smashed were determined by chance, but they also seemed necessary for its completion (or definitive incompletion).(14)

When Duchamp rebuilt the work, he was “stopping” an accidental event that had somehow made the Glass “a hundred times better.”(15) The mended cracks in the glass are not wholly invisible, but they do approach a point of disappearance–like pieces of string falling away toward some mysterious knot at infinity. Duchamp’s lines, his fractures and strands, intersect at a vanishing point in the fourth dimension, a realm that cannot be seen from our ordinary perspectives.

The Bride’s “garments” and the Three Standard Stoppages can also be discussed in terms of yet another kind of “stoppage.” Glass, as a physical substance, is an insulator, and as such is often

used to arrest or impede the flow of electrical current through circuits. Duchamp may very well have been thinking of his glass plates in these kinds of terms when he was constructing the Large Glass. (16) He also refers to the Bride’s clothing as a “cooler”:

(Develop the desire motor, consequence of the lubricious gearing.) This desire motor is the last part of the bachelor machine. Far from being in direct contact with the Bride, the desire motor is separated by an air cooler (or water). This cooler (graphically) to express the fact that the bride, instead of being merely an asensual icicle, warmly rejects (not chastely) the bachelors’ brusque offer. This cooler will be in transparent glass. Several plates of glass one above the other. In spite of this cooler, there is no discontinuity between the bachelor machine and the Bride. But the connections will be electrical and will thus express the stripping: an alternating process. Short

circuit if necessary.(17)

In addition to the terms “vêtements de la mariée” and “refroidisseur,” Duchamp uses the expression “plaques isolatrices” to describe his strips of glass. (18)

This phrase can be translated as “isolating plates” or “insulating plates.” In one of his posthumously published notes, he calls the horizontal division of the Glass a “grand isolateur,”

a “large insulator,” and explains that it should be made using “three planes five centimeters apart in transparent material (sort of thick glass) to insulate the Hanged [Pendu] from the bachelor machine.”(19)

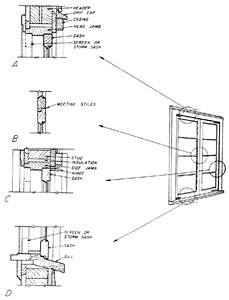

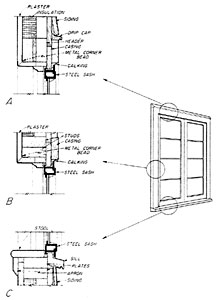

click to enlarge

Figure 10

Marcel Duchamp,

Draft Pistons, 1914

Figure 11

Marcel Duchamp,

Travelor’s Folding Item, 1916

Figure 12

Photograph of

the unbroken Large Glass

Glass may play a similar exclusionary role in the workings of the Three Standard Stoppages, but in ways that are perhaps less “transparent.” While Duchamp was apparently interested in exploring a frustrated relationship between the Bride and the Bachelors, involving as it does a “short circuit,” he was also trying to “delay” communication. Whatever talking occurs, or fails to occur, between

the separated Bride and Bachelors pertains to seeing or not seeing through words. In his notes, Duchamp explains that the Bride sends her commands to the Bachelors through the “draft pistons,”

“triple ciphers” that use a formal alphabet constructed using the Three Standard Stoppages. Because the chance-determined “draft pistons” (Fig. 10) which are deformed planes, are conceptually similar to the Stoppages, which are deformed lines, these interpretations again converge geometrically. It might also be pointed out that Duchamp’s readymade Traveler’s

Folding Item (Fig. 11) can be taken as a next logical step in this sequence: a one-dimensional

line generating a two-dimensional surface, which in its turn, generates a three-dimensional “solid”–one that can fold up.(20) By looking somewhat further into the n-dimensional implications

of these works (from the Latin implicatio, an entwining or interweaving), we may be able to ascertain how Duchamp’s arrangements, his strings and fabrics, which seem to have topological insinuations, might actually operate. Just how do the Three Standard Stoppages disappear into the Bride’s clothing?

At some later point in the construction of Three Standard Stoppages, Duchamp cut the narrow strips of canvas from their stretchers, reducing them in size in the process, and then glued them down to thick pieces of plate glass. He probably carried out this reworking when he was repairing

the Large Glass at Katherine S. Dreier’s home in Connecticut during the spring and summer of 1936.(21) Also at this time, he probably decided to put the various components of the Three Standard Stoppages into a specially constructed wooden case that resembles a croquet box. Duchamp’s decision to amplify the Stoppages along these lines was almost certainly connected with how he was repairing the “garments” of the Bride, which had presumably been pulverized when the Glass was accidentally broken in 1927. From the photograph of the unbroken Large Glass taken at the Brooklyn Museum

(Fig. 12),

it is difficult to determine how the original “garments” were constructed, but they do not appear to have been as elaborate as the repaired strips of glass. As pointed out earlier, Duchamp must have intended for the Stoppages and the “garments” to be related to one another because he used similarly colored strips of glass and parallel edge-on arrangements in their respective reconstructions.

Did Duchamp somehow “betray” his work by not actually dropping the pieces of string when he originally made the Three Standard Stoppages or when, over twenty years later, he further modified his original conception of the piece? No more than he betrayed himself by learning to appreciate the breaks in the Large Glass, or by elaborating the Bride’s “garments” when he repaired them. Such operations are, I believe, commensurate with his general attitudes about such matters.(22) Recall his statement to Katherine Kuh: “the idea of letting a piece of thread fall on a canvas was accidental, but from this accident came a carefully planned work. Most important was accepting and recognizing this accidental stimulation. Many of my highly organized works were initially suggested by just such chance encounters”(23)

Dropping pieces of string was not a rule that Duchamp had to follow, but rather a point of departure in his thinking, just as the damage to the Glass wound up inspiring his admiration.(24)

His artistic approach was analogous to scientists establishing hypotheses at the beginning of a research program, but then modifying their hypotheses once work has been carried out in the laboratory. Over the course of time, Duchamp’s examples of “hasard en conserve” (25)were supplied with controls that had not been deemed necessary in the beginning. As with the chance breakage he preserved in the Large Glass, the important thing was recognizing the accidental stimulation. Moreover, by allowing the pieces of thread to do more than simply fall upon the canvas surfaces by actually sewing them through to the other side, Duchamp could emphasize the notion that they had intersected the canvases. The encounter involved both chance and mathematics.

In works such as the Three Standard Stoppages, Duchamp creates physical analogues for the abstract concept of “intersection”: the one-dimensional pieces of string, the curved line segments, intersect the two-dimensional surfaces of the canvases (and they literally share points in common where they are sewn together). The strings are thus further implicated (I am tempted to say intertwined), along geometrical lines, with the fabric of the canvas strips. The cracks in the Glass are also a fundamental part of it. They are “inside” the broken sheets of glass, which are, in their turn, encased inside the heavy panes of glass that Duchamp used to effect their repair. In an analogous way, the ends of the strings in the Stoppages are sandwiched between the strips of canvas and the rectangles of glass that back them.

Duchamp’s works on glass are flat, but they are nonetheless rather thick. They are “spaces” that can be thought of, especially in this context, as rectangular solids. Because the sheets of glass themselves have thickness, a depth that is often layered, they can be taken as three-dimensional sections out of higher-dimensional continua. When, for example, all the configurations of the Stoppages (the strings, the templates, and the plates of glass) are considered together, their n-dimensional implications are manifest. They are one-dimensional, two-dimensional, and three-dimensional, and they have n-dimensional possibilities. Each configuration is related to the others through projection and intersection: the lines can be taken as slices out of surfaces, the surfaces as slices out of solids, and the solids as slices out of hypersolids. Esprit Pascal Jouffret, one of Duchamp’s most important mathematical sources, characterized such cuts as “infinitely thin layers.” (26)

Duchamp’s approach–moving from lines to surfaces, and from spaces to hyperspaces–is couched in terms of perspective. He considers how vanishing points and changing points of view would operate in 2-space, 3-space, 4-space, or any given n-space. He suggests using “transparent glass” and “mirror” as analogues of four-dimensional perspective systems (analogues because such systems cannot actually be constructed in three-dimensional space).(27)

Especially when the narrow sheets of glass are seen edge-on in the slots in their croquet box, they suggest their membership in an infinite series (reflections in mirrors can also imply infinite reiterations). In an interview with Pierre Cabanne, Duchamp emphasized the serial characteristics of the Stoppages: “When you’ve come to the word three, you have three million–it’s the same thing as three. I had decided that the things would be done three times to get what I wanted. My Three Standard Stoppages is produced by three separate experiments, and the form of each one is slightly different. I keep the line, and I have a deformed meter.”

(28)

he specifics of how Duchamp kept his line and used his deformed meter is worth exploring further. He tells Cabanne that he had been interested in working on glass for several reasons, including the way color “is visible from the other side.” Glass was also useful in laying out its various elements: “perspective was very important. The Large Glass constitutes a rehabilitation of perspective, which had been completely ignored and disparaged. For me, perspective became absolutely scientific.”(29)

y using linear perspective in his design, Duchamp could arrange the Bachelors’ domain in such a way that the vanishing point coincided with the horizontal division between the upper and lower panels of the Glass.

From this perspective, or from the point of view of perspective, Duchamp’s saying that a “labyrinth” lies at the “central part of the stripping-bare” is significant: the Large Glass and the Three Standard Stoppages are about occlusion.(30)

They involve unusual station points, and unusual distance points, in a perspectival system that can only be reconstructed from isolated positions outside normal space. If Duchamp were thinking of his “strips” of glass as physical puns on the notion of “stripping” the Bride, then their structure is doubly suggestive.(31) Because her clothing consists of transparent sections of glass that

are entailed with a “point de fuite,” it can be taken to include a complex set of folds, not only in the cloth of the garments, but also in the fabric of space. Recall that Traveler’s Folding Item is conceptually related to the Three Standard Stoppages.Also, the typewriter cover has been called the “Bride’s Dress.” (32)Perhaps the disappearance of the Stoppages, their dropping away toward infinity at the position of the Bride’s garments, can be taken as an interdimensional folding up, a stripping bare thatrequires orthogonal translation into higher space.

Perhaps the disappearance of the Stoppages, their dropping away toward infinity at the position of the Bride’s garments, can be taken as an interdimensional folding up, a stripping bare that requires orthogonal translation into higher space.

All of the works here under discussion are related to one another through perspectivalism (and also perspectivism). For Duchamp, the use of perspective as a system was not a matter of creating single, fixed-point ways of looking at things. It was, on the contrary, involved in dislodging viewers from their ordinary ways of understanding. And with this objective in mind, his choosing readymades during the same period he was working on the Stoppagescan be seen as a related activity. When Duchamp made his remark about Three Standard Stoppages being a readymade, but “not quite,” he continued by saying, “it’s a readymade if you wish, but a moving one.”(33)

The curving pieces of string and our shifting notions of the meaning of the readymades seem to trail off from a “vanishing point”at the horizon of our own thinking. The readymades refuse to abide

by our ordinary definitions of art, and the Stoppages allude to geometries that have challenged our traditional epistemological structures.

(34)

Their curvatures can be taken as references to non-Euclidean or topological geometries, complications that necessitate our reconsidering our vanishing points. The strings, when taken as analogues for lines of sight, are transposed, or rotated, into a hidden space.

click to enlarge

Figure 13

Girard Desargues’s discussions

of perspective

Figure 14

Girard Desargues’s discussions

of perspective

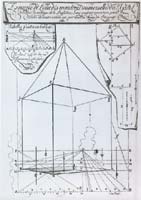

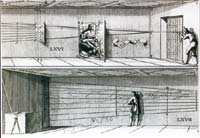

What I have in mind here can be seen in the illustrations that accompany Girard Desargues’s discussions of perspective (Figs. 13 and 14). Desargues was the first mathematician to see connections between linear perspective and conic sections, and is generally considered to be the founder of projective geometry.(35) He contributed to the “mathematicization” of perspective,

helping to transform the practical Renaissance practice of artists into the deductive science of geometers.(36)

In the illustrations, threads from lines of sight are bunched up at the plane of the picture, as if they were lying at, or perhaps it would be better to say “in,” the surface of the representation. Rather than being part of the representations, which are behind the surface and inside the three-dimensional structure represented by the picture, they are meant to be seen as separate from it.(37)

In other words, they lie in a transparent perspectival section of our visual pyramid, the surface of the picture plane that we do not normally look at in a Renaissance picture, but through.(38)

Such lines are also connected by a technological protocol involving an “arbor.” Desargues is one of the most likely sources for Duchamp’s referring to the “Bride” as an “arbor-type.”(39) The mathematician uses the term “arbre” in his discussions of perspective, as J. V. Field has explained:

“Arbre” is usually translated as “tree,” but the word can equally mean “arbor” or “axle.” Like the central axle in a machine, Desargues’ arbre is the member to which others are referred, that is, their relation to it is what chiefly defines their significance in the overall arrangement. The standard metaphorical usage whereby engineers called an axle a tree might thus have suggested to Desargues an extension of the same metaphor to provide names for subsidiary elements in the geometrical scheme.

(40)

In Desargues’ usage, an “arbre” becomes a geometrical axis.(41) His unusual vocabulary was probably inspired by his engineering and military experience, as Field suggests. Desargues employs a number of other “arbor-type” terms, such as tronc (trunk), noeud (knot), rameau (branch), souche (stump), and branche (limb). A “trunk” is a straight line that is intersected by other straight lines, “knots” are the points on the “trunk” through which the other lines pass, the other lines themselves are called “branches,” a point common to a group of segments on a line is a “stump,” one of these segments is a “limb,” etc.(42)

Desargues’ general approach of adopting an affective vocabulary for geometrical entities recalls Duchamp’s practice. For example, Desargues’ term essieu (axletree) is reminiscent of Duchamp’s term charnière (hinge). “Perhaps make a hinge picture (folding yardstick, book); develop the principle of the hinge in the displacements, first in the plane, second in space. Find an automatic description of the hinge. Perhaps introduce it in the Pendu femelle.”(43) The mechanical engineering term “axletree” refers, basically, to a fixed beam with bearings at its ends. Because the axletree has

other devices, such as wheels, branching from it, we can perhaps see why Desargues saw a comparable situation in the way geometrical projections branch off from the axes of his perspective system. In English, the similar term “arbor” was apparently used during the seventeenth

century to designate any kind of axle, but is now generally used to refer to the axles in small mechanisms such as clocks.(44)

Duchamp hints that he was familiar with these kinds of distinctions. In one of his posthumously published notes (actually notations on a folder that originally contained several other notes), he associates the Bride, the “Pendu” (femelle), with a “standard arbor (shaft model).”

(45)

In another, he connects the Bride, a “framework–standard arbor,” and a “clockwork apparatus.”

(46)

In Desargues’s way of thinking, an “arbor” or an “axletree” was analogous to an axis of rotation, a mathematical “axle,” around which the elements of his transformative system revolved. In

Duchamp’s descriptions of the complex workings of the Bride, “hinges” operate in comparable ways.

That Desargues was one of Duchamp’s sources can be given further credence by analyzing another important iconographical element of the Bride’s domain, the “nine shots,” an area of the Large Glass that was also reconstructed in 1936.(47) At a conceptual level, the “nine shots” seem to have an “Arguesian” perspectival demeanor.(48) It has recently been noticed that a number of Duchamp’s notes have been split in two.(49) One of the most interesting instances involves the “nine shots.”

A note included in his posthumously published Notes is the top part of a note published in the Green Box. Taken together, the two parts read as follows:

Make a painting on glass so that it has neither front, nor back; neither top, nor bottom. To use probably as a three-dimensional physical medium in a four-dimensional perspective.

(50)

Shots. From more or less far; on a target. This target in short corresponds to the vanishing point (in perspective). The figure thus obtained will be the projection (through skill) of the principal points of a three-dimensional body. With maximum skill, this projection would be reduced to a point (the target).

With ordinary skill this projection will be a demultiplication of the target. (Each of the new points [images of the target] will have a coefficient of displacement. This coefficient is nothing but a souvenir and can be noted conventionally. The different shots tinted from black to white according to their distance.)

In general, the figure obtained is the visible flattening (a stop on the way) of the demultiplied body. Cannon; match with tip of fresh paint. Repeat this operation 9 times, 3 times by 3 times from the same point: A–3 shots; B–3 shots, C–3 shots. A, B, and C are not in a plane and represent the schema of any object whatever of the demultiplied body.

Desargues used the unusual term “ordinance” for the orthogonals in a perspective system, the sheaf of lines that recede into the distance toward a vanishing point at the horizon. An “ordinance of lines” (ordonnance de droictes) corresponds to what we would now call a “pencil of lines” in modern geometrical parlance.(52)

Desargues, who had worked as a military engineer, may again have been prone to thinking of the trajectories of cannon shots toward a target as analogues for lines diminishing toward a vanishing point in a perspective system (or toward the vertex of a pencil of lines in a more purely geometrical representation). His term for a vanishing point (or for the vertex in an “ordinance of lines”) is “but.” He uses the expression “but d’une ordonnance,” which can be translated as “butt of an ordinance,” but which is probably more comprehensibly rendered as “target of an ordinance”). Duchamp’s line from the note above, “This target in short corresponds to the vanishing point (in perspective),” reads in French, “Ce but est en somme une correspondance du point du fuite (en perspective).”

click to enlarge

Figure 15

Marcel Duchamp, Pharmacy, 1914

Before leaving the potential influence of Desargues’ vocabulary, it might be pointed out that the notion of an “arbor-type” seems to inform several of Duchamp’s readymades. Pharmacy (Fig. 15), chosen in 1914, is a tree-filled landscape with a red and green dot added by Duchamp (at vanishing points?) on the horizon line. In addition to being a reference to the colored bottles in drugstore windows, the colors may also be a subtle reference to the techniques of anaglyphy, a practice related to stereoscopy that we know Duchamp was interested in, probably because of its n-dimensional implications.(54) In the layout of Robert Lebel’s early monograph, a design that Duchamp was largely responsible for, Pharmacy is juxtaposed to the Bottlerack (Fig. 16),

also chosen in 1914. On the facing page are the Network of Stoppages, 1914, and Cemetery of Uniforms and Liveries, No. 2(Fig. 17), 1914, the drawing that Duchamp used to transfer the design of the “capillary tubes” and the “nine malic molds” to the Large Glass.(55) Above Pharmacy and the Bottlerack is Cemetery of Uniforms and Liveries, No. 1 (Fig. 18), which in the more multi-layered French edition of the book, had a color image of Nine Malic Molds (Fig. 19) tipped in over it.(56)

click images to enlarge

- Figure 16

- Figure 17

- Marcel Duchamp,

Bottle Dryer, 1914/1964 - Marcel Duchamp,

Cemetery of Uniforms

and Liveries, No. 2, 1914

click images to enlarge

- Figure 18

- Figure 19

- Marcel Duchamp,

Cemetery of Uniforms

and Liveries, No. 1, 1913 - Marcel Duchamp,Nine

Malic Molds, 1914-15

####PAGES####

click to enlarge

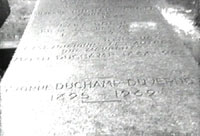

Figure 20

Photograph of Duchamp, 1942

With Desargues’ terminology such as “tree,” “trunk,” “branch,” and “limb” in mind, these works look positively geometrical. InNetwork of Stoppages, for example, the pattern of lines resemble branches, especially if the painting is rotated ninety degrees clockwise. In the background, the nude woman in “Young Man and Girl in Spring,” the first layer of Network of Stoppages, is then centered in the boughs of the tree. From this perspective, she becomes a precursor for the Bride as an “arbor-type.” In theBottlerack, the prongs appear to be rotated around a central axis (anarbre) and suggest reiterated line segments (rameaux or branches). That these interpretations can be taken seriously is reinforced by an interesting photograph of Duchamp taken in 1942 showing him standing in front of a tree that has been provided with prongs so that it can act as a bottle dryer (Fig. 20). A number of bottles, which have been hung upon this “arbre-séchoir,” can be seen behind Duchamp, and he has a network of linear shadows, which have been cast from the branches of the tree, falling across his face.(57)

The various connections here under discussion can perhaps be made more evident, in the sense of our being able to “see” into Duchamp’s n-dimensional realm, by bringing his important painting Tu m’ (Fig. 21) into the discussion.

click to enlarge

Figure 21

Marcel Duchamp, Tu m’,

1918

This work has “anamorphic” aspects and is closely related to the Three Standard Stoppages, which were used to draw a number of its curving shapes.(58) The shadows of readymades–the Bicycle Wheel, the Corkscrew, and the Hat Rack–stretch out across the surface of the picture plane suggesting an anamorphic transformation. At one level, of course, Tu m’ is about the “shadowy” existence of art objects.(59) The Corkscrew, in fact, exists only as a shadow on this painting. But

on more important levels, the work is about geometry–both Euclidean and non-Euclidean geometry. In addition to these geometries of constant curvature, Duchamp may also have been thinking about topology: some elements in the painting seem to be stretched and pulled, as if they

were elastic.(60)

The shadows of the readymades are themselves distorted transformations, and they are cast onto a surface that seems to be warped and curved, and the space behind the surface is filled with strangely bent geometrical objects.

On the right-hand side of the canvas, there is an irregular, open-sided rectangular “solid.” The left side of this solid is a white surface that recedes into the space of the canvas according to one-point perspective. From each corner of the white surface, two lines, drawn with the templates of the Three Standard Stoppages, extend at more or less right angles toward the right. One of each of these is black and the other red. The black lines at all four edges are drawn with the same template. Each set of lines at the upper boundary of the solid cross one another at two points, and each set are drawn in the same way. The two lines at the lower edges of the solid do not cross one another, and they are rotated and inverted with respect to one another.

There are also a series of color bands (twenty-four in all) extending orthogonally back into the space of the “solid,” or into its virtual shape. They seem to continue on behind it. These bands are connected to the curved line segments that comprise the ambiguous edges of the transparent solid, a volume we could think of as a 3-space with fluctuant, transparent faces. Each of the color bands is surrounded by a number of concentric circles that also recede back into the painting’s virtual space according to one-point perspective. The vanishing point coincides with the bottom edge of the canvas just to the right of center below the indexical hand, which, incidentally, is a hand-painted readymade element executed by a certain A. Klang, a sign painter Duchamp hired to carry out this task. Klang’s minuscule signature is visible near the sleeve.

Duchamp’s complex geometrical arrangement is made even more complex by the shadow of the Hat Rack, which occupies the same region of the canvas as the “solid.” On one level, the Hat Rack resembles a tree, and the shadows cast from its multiple branches suggest yet another “arbor-type.” We know that the Bride is based, in part, on the idea of the cast shadow, “as if it were the projection of a four-dimensional object.”(61)

The way the Hat Rack interacts with the “solid” is indicative of the complexities that would be involved in such spaces: The lines and color bands seem to overlay the shadow, but the shadow seems to overlay the white rectangle at the left side of the “solid.” The shadow can thus be read as both in front of and behind the chunk of space outlined and bounded by the elements of Duchamp’s design.

The spatial complexities of Tu m’ can also be seen in the recession of its orthogonals. They plunge backward in a way that is comparable to the convergence of orthogonals in the Large Glass. In the former, the lines come together just at the lower edge of the painting, in the latter, just at the upper boundary of the Bachelors’ domain. In Tu m’, the vanishing point is where the “solid” (and also its edges drawn with the Three Standard Stoppages) would disappear. In the Large Glass, the point is at the center of the three plates of glass running across the Bride’s horizon. It is where these “lines” would disappear, if rotated ninety degrees. The Bride’s garments, when thus folded up, can be taken as orthogonals to a point of intersection–the intersection of parallel lines at infinity.

In Euclidean geometry, parallel lines do not intersect. The mathematical convention that they do intersect at infinity was one of Desargues’ important contributions. (Parallel lines do seem to intersect at the vanishing point of a perspective system, which may have given Desargues his idea.) Thinking of parallel lines as meeting at infinity eventually contributed to the development of non-Euclidean geometries in the nineteenth century.(62)

The conceptual point where parallel lines meet cannot be seen, any more than the curvature of space can be perceived directly. If the curved lines in theThree Standard Stoppagesare taken as references to non-Euclidean lines of sight, then they are fundamentally hidden in “garments” of the Bride, just as the vanishing point in Tu m’seems to disappear off the edge of its hyperspatial expanse.

The left side of Tu m’ is also complicated. In addition to the shadows of the Bicycle Wheel and the Corkscrew, lines drawn with the templates of the Three Standard Stoppages are placed at the lower left-hand side of the canvas. Each of these line segments is at the edge of three curved surfaces that seem to fall back into the space of the canvas. If these irregular planes are thought of as a “pencil of surfaces” (Desargues uses the term “ordonnance de plans“), they would withdraw downward at more or less right angles to the space of the canvas toward a line of intersection located at an infinite distance. (Desargues says that a sheaf of parallel planes can be imagined converging at an “essieu,” an “axle,” just as an “ordinance of lines” can be imagined intersecting at a “point à une distance infinie.”)

(63)

The edge of the upper member of this pencil of planes is black, and it is drawn with the same “stoppage” that was used at each edge of the rectangular “solid” on the right side of the canvas. The edge of the line segment in the middle register was used as the other line at the edges of the upper boundary, and the edge of the line segment in the lower register was used as the other line at the edges of the lower boundary of the “solid.” The shadow of the Bicycle Wheel seems to overlay this arrangement of superposed curved surfaces. There is also a sequence of flat color squares receding according to a plunging perspective back from the center of the canvas into an infinite space at the upper left corner of the canvas. This arrangement of color squares seems to overlay the shadow of the Bicycle Wheel. In contrast, the shadow of the Corkscrew, which seems to spiral out from the axle of the wheel, overlays the color squares. Reading the shadows as riding on the surface of the actual canvas is thus complicated by their relationships with objects occupying the virtual space depicted “inside” the canvas. Duchamp further emphasizes the spatial oddities of his picture by using various forms of “intersection.” The corkscrew intersects the canvas by seeming to spiral into it; the safety pins pierce the surface of the canvas; and the bottle brush and the bolt go through the front side of the picture and are fastened to it from behind.

click to enlarge

Figure 22

Marcel Duchamp, Tu m’, 1918

(side view)

Duchamp is obviously playing with real and represented objects and with real and represented space in Tu m’. To further complicate the issues, he paints a trompe l’oeiltear in the surface of the canvas, which is held together by the real safety pins. In addition to these ready-made elements, the bottle brush juts out from the tear at right angles to the canvas. As an actual object, a readymade, the bottle brush casts actual shadows that can be contrasted with the virtual shadows of the Bicycle Wheel, the Corkscrew, and the Hat Rack, which Duchamp traced onto the surface with pencil. In terms of its geometry, the bottle brush is really only visible when we look at Tu m’ from the side, at an oblique angle (Fig. 22). When we view the canvas straight on, all we see is the end of the brush. Looking at the canvas from the side also allows us to see the other elements of the painting, and they seem less stretched out, less constrained by the plunging perspective. The shift is particularly apparent in the sequence of color squares at the upper left side of the canvas. In fact, we now notice that these shapes are not really squares, but parallelograms that look more “natural” from the side than from the front.

click to enlarge

Figure 23

Jean-François Nicéron,

Thaumaturgus opticus,

1646

Duchamp probably learned something about these kinds of anamorphic effects during the period he was working at the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève in Paris. One of his notes for the Large Glass, which he wrote at this time, suggests consulting the library’s collection: “Perspective. See the catalogue of the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève. The whole section on perspective: Nicéron (Father J.-F.), Thaumaturgus opticus.”(64) Many of the books on perspective available to Duchamp at the library deal with the unusual, or “aberrant,” systems used in anamorphosis. These include works by Father Jean-François Nicéron, whom Duchamp mentions by name in his note.(65)

One of Nicéron’s images from Thaumaturgus opticus (Fig. 23) is evocative of Tu m’, especially if the

sketch is fully extended (the left-hand side of the upper part continues at the right-hand side of the lower part).

(66)

Thus reconnected, the long, narrow dimensions of the image approximate those of Tu m’. Duchamp may also have seen a similarity here between the string held by the assistant in the left-hand part of the drawing and the segments of string in Three Standard Stoppages. In Nicéron’s illustration, as in perspective drawings generally, the curling end of the line is meant to indicate that it is a thread used in the construction of the image, rather than being an integral element of the imagery.

click to enlarge

Figure 24

Hans Holbein the Younger,

The French Ambassadors of King

Henri II at the court of the

English King Henry VIII, 1533

Duchamp’s thread is more complex. The strings in theThree Standard Stoppagesare themselves spaces, one-dimensional spaces, and they are intended to indicate a more difficult geometry than the one Nicéron had in mind. But Duchamp’s manner of taking an oblique view and his interest in observing a scene through a visual system rotated away from normal space, is very similar to the way Nicéron turns his outstretched images onto the wall. Duchamp’s (and Nicéron’s) procedure is also reminiscent of Hans Holbein’s famous portrait, The French Ambassadors (Fig. 24), in which a distended skull crosses the picture plane at more or less right-angles to the orthogonals of the perspective system used to construct the painting.(67)The French Ambassadorsis a favorite

image among postmodernists, primarily because it brings together two different ways of looking at objects in one picture.(68)The primary visual order, the three-dimensional space of the scientific perspective, is undermined by the anomalous skull falling across it. The abnormal space of the death’s head interpenetrates the normal space where the ambassadors live, casting a shadow across their existence. It also displaces the dominant viewing subject from a position in front of the painting to one at the side–to a position that is essentially outside the picture’s frame of reference.(69)

As the skull comes into adjustment, the painting becomes distorted, and vice versa. Jean Clair has discussed Tu m’ in terms comparable to those just used to describe Holbein’s painting. He points out that, when looked at obliquely, “the shadows of the readymades and the design of the parallelepiped straighten up.”(70) He also notices the way in which the bottle brush seems to rotate out from the surface of the canvas, changing from a “dot,” or point, into “no more than a line.” According to Clair, the function of the bottle brush is similar to that of the skull in Holbein’s picture: namely, “to expose the vanity of the painting.But this time of all paintings.”(71)

We can amplify Clair’s remarks by pointing out that, as we move to the side of Tu m’, the surface of the picture is visually rotated. If we were able to continue on around the picture in order to look at it edge on, the surface would be reduced to a line segment, from which the “line segment” of the bottle brush would extend at a right angle. The bottle brush is a readymade, a counterpart of an orthogonal, one that comes out into our space rather than receding into the space of the painting. The sequence of color squares, apparently attached to the surface of the canvas with the bolt, would presumably be receding in the opposite direction along the axis of the shaft (the axle) of the bolt back into the space of the canvas, which as we move to the side, is not only flattened into a two-dimensional surface, but further reduced to a one-dimensional line segment. Clair’s statement that as the “painting vanishes, the readymade makes its appearance,” is quite true. We could also say that the actual readymade (the bottle brush) makes its appearance as the virtual readymades and their shadows disappear. And vice versa: as the real elements of the work vanish, the virtual elements reappear.

A similar language could be used to describe the intersection of the strings with the glass plates of the Three Standard Stoppages. They trail off at right-angles, as it were, along lines that are orthogonal to the canvas strips, as if they had been rotated out of the virtual space of the “Prussian blue” into the actual space of the canvases. If the strings are analogous to “lines of sight,” they are like threads lying “in” the surface of the perspectival plane, as we have seen in Desargues’ perspective renderings (Figs. 13 and 14) or in Nicéron’s illustration (Fig. 23). In this sense, the strings can be taken as anamorphic lines crossing the representational space of the sheets of glass. Recall what Duchamp’s space was intended to show: his glass has “neither front, nor back; neither top, nor bottom,” and it can be used as a “three-dimensional physical medium” in the construction of a “four-dimensional perspective.” In the Large Glass and the Three Standard Stoppages, Duchamp was both literally and figuratively boxing and encasing the geometrical elements of his iconography–inside glass and inside an n-dimensional projective system. With Tu m’, he was also enclosing the basic elements of his own working method, and, indeed, the basic elements of painting as a general practice, inside a complex pictorial space, one with unusual curvatures.

Duchamp’s works such as the ones I have discussed in this paper, with their various projections and intersections, each in their turn folding up into the next, suggest that he was thinking about different kinds of geometries. Henri Poincaré, among the artist’s most likely mathematical sources, often discusses the interrelationships of geometries.(72)

Projective geometry, which was prefigured in Renaissance perspective and initially elaborated in the work of such seventeenth-century mathematicians as Desargues and Blaise Pascal,(73)

was later, during the nineteenth century, recognized as being central to mathematics in general. By the end of the century, both Euclidean and non-Euclidean geometry had been subsumed under the principles of projective geometry.

(74)

Projective geometry deals with properties of geometrical figures that remain invariant under transformation. It studies mappings of one figure onto another brought about by projection and section, and it tries to find qualities that remain fixed during these procedures (Desargues’ Theorem and Pascal’s Theorem describe famous examples). Twentieth-century mathematicians have invented methods of transformation that are even more general than projection and section. One of the most important of these approaches, topology, considers geometrical properties of figures that are unchanged while these figures undergo deformations such as stretching and bending. Especially in the context of the present discussion, Poincaré can be thought of as the “father

of modern topology,” (75) a subject that he referred to as analysis situs (Latin for “analysis of the site”; “topology” coming from the Greek equivalent for “study of the place”). He points out that this geometry “gives rise to a series of theorems just as closely interconnected as those of Euclid.”

(76)

Duchamp’s Tu m’ can very nearly serve as an illustration for Poincaré’s arguments. As pointed out earlier, the elongated shadows can be taken as anamorphic deformations, and thus as references to topological transformations with four-dimensional, or more generally, n-dimensional ramifications (branchings), particularly insofar as anamorphic projections seem to intersect normal space at oblique angles. In ways that are like Holbein’s famous skull, the cast shadows in Tu m’ seem to traverse the space of the picture and, in this sense, they are orthogonal to it (shadows are literally orthogonal to the surfaces on which they are cast). From the perspective of the fourth dimension, the strings in Three Standard Stoppages can also be interpreted as falling away from normal space along perpendicular lines, at least insofar as they plummet toward the horizon of the Bride. Duchamp’s cast shadows, and perhaps his cast segments of strings, are projective analogies for higher-dimensional spaces. His general approach can be seen in the following note:

For an ordinary eye, a point in a three-dimensional space hides, conceals the fourth direction of the continuum–which is to say that this eye can try to perceive physically this fourth direction by going around the said point. From whatever angle it looks at the point, this point will always be the border line of the fourth direction–just as an ordinary eye going around a mirror will never be able to perceive anything but the reflected three-dimensional image and nothing from behind.(77)

Looked at “edge-on,” in the sense of being seen undergoing an n-dimensional rotation, the individual “stoppages” can be taken as trailing off into the fourth direction of what Duchamp

calls the “étendue.”(78)From such a perspective, they would be perceived as points. The viewer equipped with a four-dimensional visual system, to use Duchamp’s words, would be able to ascertain that a “point” is always a “border line” of this “fourth direction.” At the center of the Bride’s garments, the Stoppages recede anamorphically into the labyrinth of the fourth dimension, a space that is orthogonal to normal space. Duchamp was probably aware that in descriptions of n-dimensional geometry, when n is greater than 3, the convention is to say that planes intersect at points, unlike what happens in three-dimensional space where, of course, they intersect along lines.(79) The curvature of the string does not really affect this n-dimensional argument since curvature depends upon whether or not the space is Euclidean, non-Euclidean, or whatever.(80) We can, in a sense, choose the space to have any curvature we want.(81)

In Tu m’, readymades cast shadows onto the surface of the painting, but these shadows do more than ride on the surface. As we have seen, they are interlocked in curious ways with the entities depicted in the space of the picture, convolutions that indicate Duchamp was interested in the readymades and their shadows as geometrical objects. The shadows themselves have perspectival implications and topological associations; and they are obviously seen differently under changing angles of view. As we walk “around” the picture, it presents shifting aspects. In Tu m’, and, indeed, in most of his works, Duchamp was interested in exploring both actual viewpoint and philosophical point of view, as well as the effects of the two acting together.

Such consequences were apparently on Duchamp’s mind when he chose readymades: bicycle wheels, corkscrews, and hat racks were works of art depending upon how they were perceived. He was involved with a discourse of surface (and reflective surface) in many of his works (often using glass and mirror in their construction). Because projective analogies such as shadows and falling pieces of string can be related to several different geometries, not just to n-dimensional Euclidean, or for that matter n-dimensional non-Euclidean geometry, Duchamp can entail other regimes of meaning into his system. Within any given framework, one which might, say, be used to interpret theThree Standard Stoppages, Network of Stoppages, Tu m’, the Large Glass, Nine Malic Molds, or the readymades, Duchamp understood that the implications of choosing one standpoint over another were manifold (and the etymological associations of this last term are germane here).(82)

Duchamp believed that, just as how we use a particular geometry to interpret the shape of the world is largely a matter of discretion, as Poincaré argued, so too is our choice of the interpretive frameworks that we use in making our aesthetic judgments. As an artist, Duchamp was engaged in self-referential, contemplative activities. He tried to look at himself seeing, and by so doing, to dislocate himself from the center of his own perspective.

1. Interview with Francis Roberts, “I Propose to Strain the Laws of Physics,”Art News 67 (December 1968): 62.

1. Interview with Francis Roberts, “I Propose to Strain the Laws of Physics,”Art News 67 (December 1968): 62.

2.Marcel Duchamp, Salt Seller: The Writings of Marcel Duchamp (Marchand du Sel), ed. Michel Sanouillet and Elmer Peterson (New York:Oxford University Press, 1973) 33.

2.Marcel Duchamp, Salt Seller: The Writings of Marcel Duchamp (Marchand du Sel), ed. Michel Sanouillet and Elmer Peterson (New York:Oxford University Press, 1973) 33.

3.In a note included in the Box of 1914, Duchamp says that “the Three Standard Stoppages are the meter diminished.”Ibid., 22.

3.In a note included in the Box of 1914, Duchamp says that “the Three Standard Stoppages are the meter diminished.”Ibid., 22.

4.Interview with Katherine Kuh, The Artist’s Voice: Talks with Seventeen Artists (New York: Harper & Row, 1960), 81.

4.Interview with Katherine Kuh, The Artist’s Voice: Talks with Seventeen Artists (New York: Harper & Row, 1960), 81.

5.The Network of Stoppages and its relationship to the Large Glass is explained by Richard Hamilton, The Almost Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp (London: Arts Council of Great Britain,1966), 49: “The curved lines are drawn using each template of the Standard Stoppages three times, once in each of the three groups. It was Duchamp’s intention to photograph the canvas from an angle in order to put the lines into the perspective required for the Large Glass–a means of overcoming the difficulty of transferring the amorphous curves through normal perspective projection. Photography did not prove up to the assignment and a perspective drawing had to be made.”

5.The Network of Stoppages and its relationship to the Large Glass is explained by Richard Hamilton, The Almost Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp (London: Arts Council of Great Britain,1966), 49: “The curved lines are drawn using each template of the Standard Stoppages three times, once in each of the three groups. It was Duchamp’s intention to photograph the canvas from an angle in order to put the lines into the perspective required for the Large Glass–a means of overcoming the difficulty of transferring the amorphous curves through normal perspective projection. Photography did not prove up to the assignment and a perspective drawing had to be made.”

6. Linda Dalrymple Henderson, Duchamp in Context: Science and Technology in the “Large Glass” and Related Works (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998) 63, 105; she credits Ulf Linde with drawing her attention to the different colors of the glass plates; see his Marcel Duchamp (Stockholm: Rabén and Sjögren, 1986) 138.

6. Linda Dalrymple Henderson, Duchamp in Context: Science and Technology in the “Large Glass” and Related Works (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998) 63, 105; she credits Ulf Linde with drawing her attention to the different colors of the glass plates; see his Marcel Duchamp (Stockholm: Rabén and Sjögren, 1986) 138.

7. Ulf Linde, “MARiée CELibataire,” in Walter Hopps, Ulf Linde, and Arturo Schwarz, Marcel Duchamp: Ready-Mades, etc. (1913-1964) (Paris: Le Terrain Vague, 1964), 48; see also Arturo Schwarz, The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp (New York: Abrams, 1970) 463. Henderson (cited n. 6) 105, quotes this passage from Linde in her interpretation of the Bride’s “clothing” as a condenser.

7. Ulf Linde, “MARiée CELibataire,” in Walter Hopps, Ulf Linde, and Arturo Schwarz, Marcel Duchamp: Ready-Mades, etc. (1913-1964) (Paris: Le Terrain Vague, 1964), 48; see also Arturo Schwarz, The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp (New York: Abrams, 1970) 463. Henderson (cited n. 6) 105, quotes this passage from Linde in her interpretation of the Bride’s “clothing” as a condenser.

8.Duchamp, Salt Seller (cited n. 2) 22, 33.

8.Duchamp, Salt Seller (cited n. 2) 22, 33.

9.This important discovery was made recently by Rhonda Roland Shearerand Stephen Jay Gould; see their essay “Hidden in Plain Sight:Duchamp’s Three Standard Stoppages, More Truly a `Stoppage'(An Invisible Mending) Than We Ever Realized,” Tout-Fait:The Marcel Duchamp Studies Online Journal 1, no. 1 (December1999) News <http://www.toutfait.com/duchamp.jsp?postid=677&keyword=.

9.This important discovery was made recently by Rhonda Roland Shearerand Stephen Jay Gould; see their essay “Hidden in Plain Sight:Duchamp’s Three Standard Stoppages, More Truly a `Stoppage'(An Invisible Mending) Than We Ever Realized,” Tout-Fait:The Marcel Duchamp Studies Online Journal 1, no. 1 (December1999) News <http://www.toutfait.com/duchamp.jsp?postid=677&keyword=.

10.See Craig Adcock, Marcel Duchamp’s Notes from the “Large Glass”: An N-Dimensional Analysis (Ann Arbor, Mich.:UMI Research Press, 1983) esp. 135-46, 189-90; see also, idem,”Marcel Duchamp’s `Instantanés’: Photography and the EventStructure of the Ready-Mades,” in “Event” Arts and Art Events, ed. Stephen C. Foster (Ann Arbor, Mich.: UMI Research Press, 1988) 239-66.

10.See Craig Adcock, Marcel Duchamp’s Notes from the “Large Glass”: An N-Dimensional Analysis (Ann Arbor, Mich.:UMI Research Press, 1983) esp. 135-46, 189-90; see also, idem,”Marcel Duchamp’s `Instantanés’: Photography and the EventStructure of the Ready-Mades,” in “Event” Arts and Art Events, ed. Stephen C. Foster (Ann Arbor, Mich.: UMI Research Press, 1988) 239-66.

11.Duchamp’s Three Standard Stoppages and Marey’s chronophotographs are discussed by Jean Clair, Duchamp et la photographie: Essai d’analyse d’un primat technique sur le développement d’une oeuvre (Paris: Éditions du Chêne, 1977) 26-28, 52. For statements by Duchamp about chronophotography, see his interviews with James Johnson Sweeney, “Eleven Europeans in America,” Museum of Modern Art Bulletin 13 (1946): 19-21, reprinted in Duchamp, Salt Seller, 123-26; and with Pierre Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, trans. Ron Padgett (New York: Viking Press, 1971) 34. For Marey’s work, see Étienne-Jules Marey, Le Mouvement (Paris: G. Masson, Éditeur, 1894).

11.Duchamp’s Three Standard Stoppages and Marey’s chronophotographs are discussed by Jean Clair, Duchamp et la photographie: Essai d’analyse d’un primat technique sur le développement d’une oeuvre (Paris: Éditions du Chêne, 1977) 26-28, 52. For statements by Duchamp about chronophotography, see his interviews with James Johnson Sweeney, “Eleven Europeans in America,” Museum of Modern Art Bulletin 13 (1946): 19-21, reprinted in Duchamp, Salt Seller, 123-26; and with Pierre Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, trans. Ron Padgett (New York: Viking Press, 1971) 34. For Marey’s work, see Étienne-Jules Marey, Le Mouvement (Paris: G. Masson, Éditeur, 1894).

12.Schwarz (cited n. 7) 444, says that Duchamp’s chose his title after seeing a sign on a Parisian shop advertizing “stoppage”; see also Francis Naumann, The Mary and William Sisler Collection (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1984) 168-71. Jennifer Gough-Cooper and Jacques Caumont, “Ephemerides on and about Marcel Duchamp and Rrose Sélavy, 1887-1968,” in Marcel Duchamp: Work and Life, ed. Pontus Hulten (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1993), in their entry for May 19, 1914, have suggested that the sign read “stoppages et talons,” which would imply fixing holes in the heels (talons) of socks and stockings.

12.Schwarz (cited n. 7) 444, says that Duchamp’s chose his title after seeing a sign on a Parisian shop advertizing “stoppage”; see also Francis Naumann, The Mary and William Sisler Collection (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1984) 168-71. Jennifer Gough-Cooper and Jacques Caumont, “Ephemerides on and about Marcel Duchamp and Rrose Sélavy, 1887-1968,” in Marcel Duchamp: Work and Life, ed. Pontus Hulten (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1993), in their entry for May 19, 1914, have suggested that the sign read “stoppages et talons,” which would imply fixing holes in the heels (talons) of socks and stockings.

13.Robert Lebel, Marcel Duchamp, with texts by André Breton and H.-P. Roché, trans. George Heard Hamilton (New York: Grove Press, 1959) 54.

13.Robert Lebel, Marcel Duchamp, with texts by André Breton and H.-P. Roché, trans. George Heard Hamilton (New York: Grove Press, 1959) 54.

14.In an interview with James Johnson Sweeney filmed at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and broadcast as part of the “Wisdom” series on NBC television in January 1956, Duchamp himself put forward a similar argument: “I like the cracks, the way they fall. You remember how it happened in 1926, in Brooklyn? They put the two panes on top of one another on a truck, flat, not knowing what they were carrying, and bounced for sixty miles into Connecticut, and that’s the result! But the more I look at it the more I like the cracks: they are not like shattered glass. They have a shape. There is a symmetry in the cracking, the two crackings are symmetrically arranged and there is more, almost an intention there, an extra–a curious intention that I am not responsible for, a ready-made intention, in other words, that I respect and love.” “A Conversation with Marcel Duchamp,” reprinted in Duchamp,Salt Seller (cited n. 2) 127-37, the quote is from p. 127. The Large Glass was on view at the “International Exhibition of Modern Art” at the Brooklyn Museum between November 17, 1926, and January 9, 1927. It thus must have been broken on its way back to Katherine S. Dreier’s home in West Redding, Connecticut, in early 1927, rather than in 1926 as Duchamp says.

14.In an interview with James Johnson Sweeney filmed at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and broadcast as part of the “Wisdom” series on NBC television in January 1956, Duchamp himself put forward a similar argument: “I like the cracks, the way they fall. You remember how it happened in 1926, in Brooklyn? They put the two panes on top of one another on a truck, flat, not knowing what they were carrying, and bounced for sixty miles into Connecticut, and that’s the result! But the more I look at it the more I like the cracks: they are not like shattered glass. They have a shape. There is a symmetry in the cracking, the two crackings are symmetrically arranged and there is more, almost an intention there, an extra–a curious intention that I am not responsible for, a ready-made intention, in other words, that I respect and love.” “A Conversation with Marcel Duchamp,” reprinted in Duchamp,Salt Seller (cited n. 2) 127-37, the quote is from p. 127. The Large Glass was on view at the “International Exhibition of Modern Art” at the Brooklyn Museum between November 17, 1926, and January 9, 1927. It thus must have been broken on its way back to Katherine S. Dreier’s home in West Redding, Connecticut, in early 1927, rather than in 1926 as Duchamp says.

15.Interview with Cabanne (cited n. 11) 75: “It’s a lot better with the breaks, a hundred times better. It’s the destiny of things.” See also Mark B. Pohlad, “`Macaroni Repaired is Ready for Thursday . . .’: Marcel Duchamp as Conservator,” Tout-Fait: The Marcel Duchamp Studies Online Journal 1, no. 3 (December 2002) Articles <http://www.toutfait.com/duchamp.jsp?postid=910&keyword=>.

15.Interview with Cabanne (cited n. 11) 75: “It’s a lot better with the breaks, a hundred times better. It’s the destiny of things.” See also Mark B. Pohlad, “`Macaroni Repaired is Ready for Thursday . . .’: Marcel Duchamp as Conservator,” Tout-Fait: The Marcel Duchamp Studies Online Journal 1, no. 3 (December 2002) Articles <http://www.toutfait.com/duchamp.jsp?postid=910&keyword=>.

16.Henderson (cited n. 6) discusses the Bride’s “garments” and their relationship with the Three Standard Stoppages in terms of “telegraphy,” comparing the glass plates in these works to such devices as condensers and insulators; see especially her chap. 8, “The Large Glass as a Painting of Electromagnetic Frequency.”

16.Henderson (cited n. 6) discusses the Bride’s “garments” and their relationship with the Three Standard Stoppages in terms of “telegraphy,” comparing the glass plates in these works to such devices as condensers and insulators; see especially her chap. 8, “The Large Glass as a Painting of Electromagnetic Frequency.”

17.Duchamp, Salt Seller (cited n. 2) 39.

17.Duchamp, Salt Seller (cited n. 2) 39.

18.Marcel Duchamp, Notes, ed. and trans. Paul Matisse (Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou, 1980), no. 154.

18.Marcel Duchamp, Notes, ed. and trans. Paul Matisse (Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou, 1980), no. 154.

19.Marcel Duchamp, Notes, ed. and trans. Paul Matisse (Paris:Centre Georges Pompidou, 1980), no. 154.

19.Marcel Duchamp, Notes, ed. and trans. Paul Matisse (Paris:Centre Georges Pompidou, 1980), no. 154.

20.For a more complete discussion of these ideas, see Craig Adcock, “Conventionalism in Henri Poincaré and Marcel Duchamp,” Art Journal 44 (fall 1984): 249-58; see also idem, Marcel Duchamp’s Notes (cited n. 10) 149-54.

20.For a more complete discussion of these ideas, see Craig Adcock, “Conventionalism in Henri Poincaré and Marcel Duchamp,” Art Journal 44 (fall 1984): 249-58; see also idem, Marcel Duchamp’s Notes (cited n. 10) 149-54.

21.Ecke Bonk, Marcel Duchamp, The Box in a Valise: de ou par Marcel Duchamp ou Rrose Sélavy, trans. David Britt (New York: Rizzoli, 1989) 216-20. See also the letters Duchamp sent to Dreier during late 1935 and early 1936 in Affectionately, Marcel: The Selected Correspondence of Marcel Duchamp, ed. Francis M. Naumann and Hector Obalk (Ghent and Amsterdam: Ludion Press, 2000) 199-207.

21.Ecke Bonk, Marcel Duchamp, The Box in a Valise: de ou par Marcel Duchamp ou Rrose Sélavy, trans. David Britt (New York: Rizzoli, 1989) 216-20. See also the letters Duchamp sent to Dreier during late 1935 and early 1936 in Affectionately, Marcel: The Selected Correspondence of Marcel Duchamp, ed. Francis M. Naumann and Hector Obalk (Ghent and Amsterdam: Ludion Press, 2000) 199-207.

22.For a discussion of Duchamp’s approach, along somewhat different lines, see Craig Adcock, “Duchamp’s Way: Twisting Our Memory of the Past `For the Fun of It,'” in The Definitively

22.For a discussion of Duchamp’s approach, along somewhat different lines, see Craig Adcock, “Duchamp’s Way: Twisting Our Memory of the Past `For the Fun of It,'” in The Definitively

Unfinished Marcel Duchamp, ed. Thierry de Duve (Halifax: Nova Scotia College of Art and Design; Cambridge and London: MIT Press, 1991) 311-34.

23.Interview Kuh (cited n. 4) 92.

23.Interview Kuh (cited n. 4) 92.

24.Interview with Cabanne (cited 11) 75.

24.Interview with Cabanne (cited 11) 75.

25.Duchamp, Duchamp du Signe (cited n. 18) 50.

25.Duchamp, Duchamp du Signe (cited n. 18) 50.

26.Esprit Pascal Jouffret, Traité élémentaire de géométrie à quatre dimensions et introduction à la géométrie à n dimensions (Paris: Gauthier-Villars, 1903), xxviii. For a more detailed discussion of Jouffret’s usage and its importance for Duchamp’s concept of inframince, see Adcock, Marcel Duchamp’s Notes (cited n. 10) 48-55.

26.Esprit Pascal Jouffret, Traité élémentaire de géométrie à quatre dimensions et introduction à la géométrie à n dimensions (Paris: Gauthier-Villars, 1903), xxviii. For a more detailed discussion of Jouffret’s usage and its importance for Duchamp’s concept of inframince, see Adcock, Marcel Duchamp’s Notes (cited n. 10) 48-55.

27. Duchamp, Salt Seller (cited n. 2), 88. For more detailed analyses of Duchamp’s use of glass and mirror as metaphors for four-dimensional perspective, see Adcock, Marcel Duchamp’s Notes (cited n. 10), esp. 75-79, 146-49; also idem, “Geometrical Complication in the Art of Marcel Duchamp,” Arts Magazine 58 (January 1984): 105-09

27. Duchamp, Salt Seller (cited n. 2), 88. For more detailed analyses of Duchamp’s use of glass and mirror as metaphors for four-dimensional perspective, see Adcock, Marcel Duchamp’s Notes (cited n. 10), esp. 75-79, 146-49; also idem, “Geometrical Complication in the Art of Marcel Duchamp,” Arts Magazine 58 (January 1984): 105-09

28.Interview with Cabanne (cited n. 11) 47.

28.Interview with Cabanne (cited n. 11) 47.

30.Duchamp, Notes (cited n. 19) no. 139; see also no.153.

30.Duchamp, Notes (cited n. 19) no. 139; see also no.153.

31.See Henderson (cited n. 6) 63: “The Stoppages‘ arrangement of one clear and two greenish glass plates parallels exactly that of the glass strips mounted on the Large Glass: the top strip is clear and the two below are greenish in hue. Because Duchamp located the Bride’s “Clothing” at the midsection of the Glass, the gravity-drawn thread lines of the Stoppages may have become for him a metonymical sign for the fallen garment of the Bride.”

31.See Henderson (cited n. 6) 63: “The Stoppages‘ arrangement of one clear and two greenish glass plates parallels exactly that of the glass strips mounted on the Large Glass: the top strip is clear and the two below are greenish in hue. Because Duchamp located the Bride’s “Clothing” at the midsection of the Glass, the gravity-drawn thread lines of the Stoppages may have become for him a metonymical sign for the fallen garment of the Bride.”

32.Linde, “MARiée CELibataire” (cited n. 7) 60; Arturo Schwarz (cited n. 7, p. 463) says that Duchamp related Traveler’s Folding Item to a “feminine skirt.” See also Molly Nesbit and Naomi Sawelson-Gorse, “Concept of Nothing: New Notes by Marcel Duchamp and Walter Arensberg,” The Duchamp Effect: Essays, Interviews, Round Table, ed. Martha Buskirk and Mignon Nixon (Cambridge, Mass., and London: MIT Press, 1996) 131-75. For a number of fascinating connections between Duchamp’s Traveler’s Folding Item and the world at large, see Rhonda Roland Shearer, “Marcel Duchamp: A Readymade Case for Collecting Objects of Our Cultural Heritage along with Works of Art,” Tout-Fait: The Marcel Duchamp Studies Online Journal 1, no. 3 (December 2000) Collections <http://www.toutfait.com/duchamp.jsp?postid=1090&keyword=>.

32.Linde, “MARiée CELibataire” (cited n. 7) 60; Arturo Schwarz (cited n. 7, p. 463) says that Duchamp related Traveler’s Folding Item to a “feminine skirt.” See also Molly Nesbit and Naomi Sawelson-Gorse, “Concept of Nothing: New Notes by Marcel Duchamp and Walter Arensberg,” The Duchamp Effect: Essays, Interviews, Round Table, ed. Martha Buskirk and Mignon Nixon (Cambridge, Mass., and London: MIT Press, 1996) 131-75. For a number of fascinating connections between Duchamp’s Traveler’s Folding Item and the world at large, see Rhonda Roland Shearer, “Marcel Duchamp: A Readymade Case for Collecting Objects of Our Cultural Heritage along with Works of Art,” Tout-Fait: The Marcel Duchamp Studies Online Journal 1, no. 3 (December 2000) Collections <http://www.toutfait.com/duchamp.jsp?postid=1090&keyword=>.

33.Interview with Roberts (cited n. 1) 62.

33.Interview with Roberts (cited n. 1) 62.

34.Hilary Putnam, for example, has said that “the overthrow of Euclidean geometry is the most important event in the history of science for the epistemologist.” See his Mathematics, Matter and Method, 2d ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979), x.

34.Hilary Putnam, for example, has said that “the overthrow of Euclidean geometry is the most important event in the history of science for the epistemologist.” See his Mathematics, Matter and Method, 2d ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979), x.

35.For one of the most complete discussions of Desargues’ work and for the most reliable translations of his texts, see J. V. Field and J. J. Gray, The Geometrical Work of Girard Desargues (New York: Springer-Verlag, 1987). Desargues’ principal essay on projective geometry is Brouillon proiect d’une atteinte aux evenemens des rencontres du Cone avec un Plan (Paris, 1639); his earlier work on perspective, is entitled Exemple de l’une des manieres universelles du S.G.D.L. touchant la pratique de la perspective sans emploier aucun tiers point, de distance ny d’autre nature, qui foit hors du champ de l’ouvrage (Paris, 1636). “S.G.D.L.” is an abbreviation for “Sieur Girard Desargues Lyonnais.” This twelve page brochure included the two high-quality engraved illustrations reproduced here, which are almost certainly by Abraham Bosse (1602-1676); see J. V. Field, The Invention of Infinity: Mathematics and Art in the Renaissance (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1997) 192. Desarques’ perspective treatise was included as an appendix in Bosse’s Maniere universelle de Mr. Desargues, pour pratiquer la perspective par petit-pied, comme le Geometral (Paris, 1648)

35.For one of the most complete discussions of Desargues’ work and for the most reliable translations of his texts, see J. V. Field and J. J. Gray, The Geometrical Work of Girard Desargues (New York: Springer-Verlag, 1987). Desargues’ principal essay on projective geometry is Brouillon proiect d’une atteinte aux evenemens des rencontres du Cone avec un Plan (Paris, 1639); his earlier work on perspective, is entitled Exemple de l’une des manieres universelles du S.G.D.L. touchant la pratique de la perspective sans emploier aucun tiers point, de distance ny d’autre nature, qui foit hors du champ de l’ouvrage (Paris, 1636). “S.G.D.L.” is an abbreviation for “Sieur Girard Desargues Lyonnais.” This twelve page brochure included the two high-quality engraved illustrations reproduced here, which are almost certainly by Abraham Bosse (1602-1676); see J. V. Field, The Invention of Infinity: Mathematics and Art in the Renaissance (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1997) 192. Desarques’ perspective treatise was included as an appendix in Bosse’s Maniere universelle de Mr. Desargues, pour pratiquer la perspective par petit-pied, comme le Geometral (Paris, 1648)

36.For a discussion of this trend, see Martin Kemp, “Geometrical Perspective from Brunelleschi to Desargues: A Pictorial Means or an Intellectual End?” Proceedings of the British Academy 70 (1984): 89-132.

36.For a discussion of this trend, see Martin Kemp, “Geometrical Perspective from Brunelleschi to Desargues: A Pictorial Means or an Intellectual End?” Proceedings of the British Academy 70 (1984): 89-132.

37.Field (cited n. 35) 192-95.

37.Field (cited n. 35) 192-95.

38.Erwin Panofsky, Perspective as Symbolic Form, trans. Christopher S. Wood (New York: Zone Books, 1991); originally published as “Die Perspektive als `symbolische Form,'” in Vorträge der Bibliothek Warburg, 1924-1925 (Leipzig and Berlin, 1927) 258-330. For a discussion of Panofsky’s contributions to perspective studies, particularly strong in its analysis of sources, see Kim Veltman, “Panofsky’s Perspective: A Half Century Later,” in La Prospettiva rinascimentale: Codificazione e trasgressioni, vol. 1, ed. Marisa Dalai Emiliani (Florence: Centro Di, 1980) 565-84.

38.Erwin Panofsky, Perspective as Symbolic Form, trans. Christopher S. Wood (New York: Zone Books, 1991); originally published as “Die Perspektive als `symbolische Form,'” in Vorträge der Bibliothek Warburg, 1924-1925 (Leipzig and Berlin, 1927) 258-330. For a discussion of Panofsky’s contributions to perspective studies, particularly strong in its analysis of sources, see Kim Veltman, “Panofsky’s Perspective: A Half Century Later,” in La Prospettiva rinascimentale: Codificazione e trasgressioni, vol. 1, ed. Marisa Dalai Emiliani (Florence: Centro Di, 1980) 565-84.

39.Duchamp, Salt Seller (cited n. 2) 42: “This cinematic blossoming, which expresses the moment of the stripping, should be grafted onto an arbor-type of the bride. This arbor-type has its roots in the desire-gears, but the cinematic effects of the electrical stripping, transmitted to the motor with quite feeble cylinders, leave (plastic necessity) the arbor-type at rest. (Graphically, in Munich I had already made two studies of this arbor type.) Do not touch the desire-gears, which by giving birth to the arbor-type, find within this arbor-type the transmission of the desire to the blossoming into stripping, voluntarily imagined by the bride desiring.”

39.Duchamp, Salt Seller (cited n. 2) 42: “This cinematic blossoming, which expresses the moment of the stripping, should be grafted onto an arbor-type of the bride. This arbor-type has its roots in the desire-gears, but the cinematic effects of the electrical stripping, transmitted to the motor with quite feeble cylinders, leave (plastic necessity) the arbor-type at rest. (Graphically, in Munich I had already made two studies of this arbor type.) Do not touch the desire-gears, which by giving birth to the arbor-type, find within this arbor-type the transmission of the desire to the blossoming into stripping, voluntarily imagined by the bride desiring.”

40.J. V. Field, “Linear Perspective and the ProjectiveGeometry of Girard Desargues,” Nuncius 2,no. 2 (1987): 3-40.

40.J. V. Field, “Linear Perspective and the ProjectiveGeometry of Girard Desargues,” Nuncius 2,no. 2 (1987): 3-40.

41.Henderson (cited n. 6) does not refer to Desargues in her discussion of the Bride as an “arbor-type.” She argues that because an “arbor” is an “axle,” Duchamp’s usage should be interpreted as a reference to such devices as the shafts in automobile transmissions or electrical generators. I completely agree that Duchamp could have had these kinds of associations in mind along with his taking an “arbre” to refer to a geometrical axis of rotation.

41.Henderson (cited n. 6) does not refer to Desargues in her discussion of the Bride as an “arbor-type.” She argues that because an “arbor” is an “axle,” Duchamp’s usage should be interpreted as a reference to such devices as the shafts in automobile transmissions or electrical generators. I completely agree that Duchamp could have had these kinds of associations in mind along with his taking an “arbre” to refer to a geometrical axis of rotation.

42.Field and Gray (cited n. 35) 61-175.

42.Field and Gray (cited n. 35) 61-175.

43.Duchamp, Salt Seller (cited n. 2) 27; see also idem, Duchamp du Signe (cited n. 18) 42.

43.Duchamp, Salt Seller (cited n. 2) 27; see also idem, Duchamp du Signe (cited n. 18) 42.

44.Field, “Linear Perspective and the Projective Geometry of Girard Desargues” (cited n. 40) 21.

44.Field, “Linear Perspective and the Projective Geometry of Girard Desargues” (cited n. 40) 21.