* This essay was originally intended to serve as the second half of an article dealing with the general topic of Duchamp and money. The first part—which deals with the subject of how Duchamp used money in both his art and life—appeared in the April 2003 issue of Art in America.

In the nearly thirty-five years that have passed since Duchamp’s death, there has been a steady increase in the attention devoted to his work, not only by art historians, but also within the world of contemporary art. Certainly the retrospective exhibitions that were held in Philadelphia and New York (1973), Paris (1977), and Venice (1993), contributed to the appreciation of his work, as did the numerous articles and books on the artist that have appeared with consistency over the years. But exactly how much this kind of attention affects the financial evaluation of his work is difficult to determine with any degree of accuracy. Historical importance and contemporary relevance are certainly factors that should be taken into consideration when one attempts to evaluate a given work of art, but, as we shall see, taste (a factor Duchamp’s work confronts by its very nature) and quantity (which he attempted to control) are even more relevant concerns in a fickle and continuously changing art market.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Arturo Schwarz, Duchamp’s dealer in Milan, continued to sell examples of the artist’s work, as did a number of galleries in other parts of Europe and the United States. Schwarz still had nearly all of the readymades that were produced in the 1964 edition. At the time they were issued, the complete set was priced at $25,000. So far as is known, there were only two takers: the National Gallery of Canada, and the Cordier & Ekstrom Gallery in New York. The Canadian purchase took place through the efforts of Brydon Smith, Curator of Contemporary Art at the museum. In 1970, Smith approached Schwarz with an interest in purchasing the entire set of readymades, but discovered that there was not enough money left in the museum’s purchase account for that particular year. The following year the museum experienced a surplus in their operating budget, and through a skillful reappropriation of these funds, they were able to make the acquisition. “It was rather in the spirit of Duchamp,” Smith later mused, for the readymades were purchased “from an account usually reserved for office supplies and other such useful materials.”

The second set of readymades ended up in an even more unlikely institution: the Art Museum of Indiana University in Bloomington, Indiana. In 1971, Thomas T. Solley, director of the museum, was approached by Arne Ekstrom, owner of the Cordier & Ekstrom Gallery, through which Solley had made various purchases over the years. Ekstrom wanted to know if he would be interested in acquiring the complete set of readymades (which Ekstrom had purchased from Schwarz in the mid-1960s for a Duchamp exhibition at his gallery, and which were then languishing in his storage facility). Through the museum, Solley contacted a donor who agreed to facilitate the purchase, and the readymades were shipped out to Bloomington, where, to this very day, they remain on public display in the University Art Museum. Even though the purchase price had risen to $35,000 (a considerable sum in those years), the expenditure was not challenged by members of the art faculty, but was, surprisingly, applauded.In the end, it would prove to be a very wise investment, for, as we

shall see, within thirty years the entire set of Duchamp readymades would escalate in value to well over one hundred times that amount.

click images to enlarge

- A Collection of Dada Art, Sotheby’s London,

December 4, 1985, catalogue (cover).

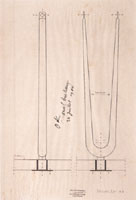

- Marcel Duchamp, Bicycle Wheel, 1916/68,

lot no. 251 in A Collection of Dada Art.

In contrast to the success of these private sales, the first attempt to sell the readymades at public auction proved a surprising and unexpected disappointment. In 1985, Sotheby’s in London offered “A Collection of Dada Art,” which was identified in the catalogue as “property of a Swiss collection, formerly the collection of Arturo Schwarz, Milan” (Fig. 1). Schwarz had closed his gallery ten years earlier, and the 261 separate lots in this auction represented the remaining inventory from his commercial activities (he had kept the most important pieces for his own private collection). Included was work by some of the most notable of Dada artists: Hans Richter, Hanna Hoch, Max Ernst, George Grosz, Marcel Janco, Kurt Schwitters, Francis Picabia, Man Ray, and a selection of works by Duchamp. The sale concluded with the complete set of readymades issued by the Galleria Schwarz in 1964 (Fig. 2), offered, however, as separate lots. Bidding for these items was anything but brisk. In the end, six of the smaller readymades sold, but at prices that were only about half their pre-sale estimates. This would indicate that the auction house set the reserve (the lowest price at which a work can be sold) unusually low, far lower than the low of the estimate. Despite this strategy, seven of the more important readymades — Bicycle Wheel, Bottle Rack, In Advance of the Broken Arm, Fountain, among others — failed to sell. Nevertheless, within a few weeks after the sale, Sotheby’s managed to find buyers for all the readymades that still remained in their possession, but at prices that were a fraction of the pre-sale estimates.

click to enlarge

Figure 3

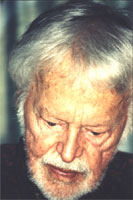

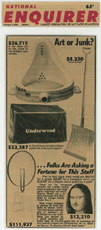

“Art or Junk?,” The National Enquirer,

London edition, February 4, 1986.

The lack of success in selling these works did not prevent at least one newspaper— the anything-but-respected National Enquirer — from asking its readers if the readymades were “Art or Junk?” (Fig. 3). The tabloid reproduced a selection of the objects with their prices, alerting their readers to the fact that “folks are asking a fortune for this stuff.” When an expert at Sotheby’s was asked to explain the “outrageous amounts… these wacky ‘artworks’ are worth,” she wisely replied: “It requires a great deal of knowledge of twentieth-century art to understand these pieces.” Few would argue with that explanation; to understand the prices would have required a great deal of knowledge of twentieth-century art, but also a thorough knowledge of the market in twentieth-century art.

The ideas Duchamp introduced continue to represent an influential force in the world of contemporary art, a factor that — one would assume — affects the financial evaluation assigned his work. This point was dramatically demonstrated in 1997 when one of the examples of Fountain from the Schwarz edition was offer by Sotheby’s in New York as part of their autumn sale of Contemporary Art (Fig. 4). Fourteen years had passed since the Schwarz sale in London when this same work failed to sell, but times had changed. The work was considered so important that the auction house decided to reproduce it on the front cover of its catalogue, and, in a clever decision (since the two works seem to share a common theme), Robert Gober’s Drain was chosen to appear on the back cover. I was asked by the auction house to write an entry on

click to enlarge

Contemporary Art, Sotheby’s

New York, November 17, 1999,

catalogue(front cover).

Contemporary Art, Sotheby’s

New York, November 17, 1999,

catalogue (back cover: reproduced:

Robert Gober, Drain,

edition no. 2/8, cast pewter,

4 ¼ in. x 4 ¼ in. x 3 in., 1989).

Figure 4

Fountain, which turned out to be an essay of six pages that provided not only a history of the original urinal, but the making of subsequent replicas, including the Schwarz edition. The organizers of the auction decided upon a pre-auction estimate of $1,000,000 — 1,500,000, an unprecedented amount for a work like this at auction, but perfectly in keeping with their knowledge of private sales. A year earlier, it was generally known within the art world that under the directorship of David Ross, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art purchased an example of Fountain from the collection of Charles Saatchi for $1,000,000. This information may very well have contributed to the success of the Sotheby’s sale, for in the end, Fountain was purchased by Dimitri Daskalopoulos, a Greek collector, for $1,762,500, a new record for a work by Duchamp at auction. When questioned after the sale, Daskalopoulos said that he had purchased the piece because “for me, it represents the origins of contemporary art.”

A knowledge of prior sales may have contributed to the exceptionally high price paid for this work, but there were other factors as well. In the days immediately preceding the sale, Daskalopoulos’s advisor in art purchases called me several times from Athens to inquire exactly how this particular

example of Fountain differed from one owned by Dakis Joannou, another Greek collector of modern art. Dakis’s Fountain, I explained, came from the collection of Andy Warhol, but it did not bear the important brass plaque that identified the work as part of the edition of eight signed and numbered examples.So far as I could determine, the work being sold by Sotheby’s was the very last example of Fountain from the Schwarz edition that was ever likely going to be made available for sale (the location of the seven other examples of this work from the complete edition of eight accompanied my essay in the catalogue).

It should also be noted that as a collector of contemporary art, Daskalopoulos was certainly familiar with the high prices that were usually paid to secure important work. In fact, the two lots that directly preceded the sale of Fountain in the Sotheby’s auction sold for prices that either equaled or exceeded the amount paid for this particular readymade: a Jasper Johns drawing of a Flag sold for $1,762,500, and one of Andy Warhol’s paintings of wanted men (which was compared in the catalogue to Duchamp’s Wanted Poster of 1923/63) sold for $1,982,500. Even these prices were not exceptional when compared with the record-breaking $11 million dollars that was paid for a painting by Mark Rothko that followed a few lots later in the same sale. When it came to assessing the success of this sale, however, few neglected to mention the record-breaking price for a work by Duchamp.

####PAGES####

click to enlarge

Figure 5

Marcel Duchamp: Nine Works,

Sotheby’s London, December 7, 1999,catalogue (cover).

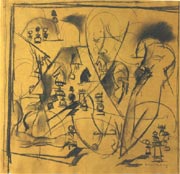

Figure 6

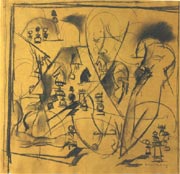

Marcel Duchamp, Study for

a Portrait of Chess Players,

1911, charcoal on paper, 19 ½ x 19 7/8 in.

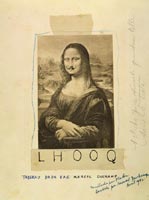

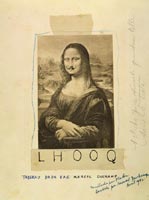

Figure 7

Marcel Duchamp, L.H.O.O.Q.,

1920/42, rectified readymade

(made by Francis Picabia),

9 ¼ x 7 inches (23.8 x 18.8 cm).

Francis M. Naumann Fine Art, New York.

Three weeks after the sale took place in New York, an auction of Impressionist and Modern Art was held at Sotheby’s in London that included nine works by Duchamp ( Fig. 5). It was generally known that all nine of these works were owned by Georges Marci, a Swiss collector who had assembled the works over the course of the prior decade. These works were featured in a separate catalogue, for which I was again asked to write the introduction. Like the readymades, most of the items offered were produced in editions: the three erotic objects made in an edition of 8 to 10 examples, a reproduction of the L.H.O.O.Q.issued in an edition of 35, and a valise, produced in an edition of 150 examples. The only unique work was Study for a Portrait of Chess Players ( Fig. 6), a magnificent large Cubist drawing that Duchamp had made in 1911, but which he had given to Louise Varèse during his early years in New York (and which remained in her possession until her death in 1988). This drawing was given an estimate of 350,000-450,000 BP, and sold for an impressive 529,500 BP. It may have been the attraction of this single work that caused most of the other works by Duchamp to sell within or in excess of their pre-sale estimates. Only the valise — which was accompanied by five original letters from Duchamp to Poupard-Lieussou (the original owner of this item)—failed to sell. The pre-auction estimate was $165,000 – $206,000, far in excess of the amount that had ever been paid for a comparable work at auction, which was, apparently, the main factor that inhibited bidding.

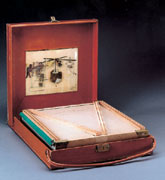

The exceptionally high price paid for a work by Duchamp may have impressed many, but it is not a great deal of money when compared with the amount that would have been paid, for example, for an important drawing by Picasso from the height of his Cubist period. Indeed, when the prices of Duchamp’s work are compared with those paid for anything even remotely similar by Picasso, the differences can be astronomical. In a sale of Impressionist and Modern Art held at Christie’s New York in the fall of 2000, I wrote entries for two works by Duchamp: a replica by Francis Picabia of his famous L.H.O.O.Q. ( Fig. 7)(with an estimated value of $700,000-900,000), and a deluxe edition of the valise ( Fig. 8) (estimated at $800,000-1,200,000).The auction would also include a rare Blue Period painting by PicassoFemme aux bras croisés ( Fig. 9), a woman with arms crossed that—as a friend of mine recently observed—resembled (coincidentally) the positioning of La Jocconde in Duchamp’sL.H.O.O.Q..When I found out about the Picasso, I requested that I be allowed to write entries on Duchamp that were at least as long as the one that was being written for this painting, though I was well that the Picasso would have a higher estimate (the catalogue stated “estimate upon request,” but the experts felt that the painting was worth between 30 to 40 million dollars). To my surprise, the auction house complied. Of course, I knew that the length of my entry would not affect the outcome of the sale, but I wanted Duchamp to be accorded the same historical respect as Picasso. On the night of the auction, the Picasso sold for over 55 million dollars, and, so far as I could tell, the two works by Duchamp did not receive even a single bid.

click images to enlarge

- Marcel Duchamp, The Box in a Valise, 1943, deluxe edition made

for Kay Boyle (containing original Bachelor’s Domain,

a hand-colored pochoir reproduction on celluloid of the lower

section of the Large Glass).

- Pablo Picasso, Femme aux

bras croisés, 1901-02, oil

on canvas,32 x 23 in. (81.3 x 58.4 cm).

Private Collection.

here are several explanations that could account for this failure. First, the works by Duchamp had been recently on the market: the L.H.O.O.Q. had come from a Duchamp exhibition at a commercial gallery in New York (a show that I had organized), where the asking price for this work had been set at $1,300,000 (considerably more than the auction estimate), and the valise had been offered privately by several dealers in Europe and in the United States at prices that ranged from $650,000 to $750,000 (still lower than the auction estimate).But even more importantly, the works by Duchamp were placed in the wrong context. The sale included paintings by some of the most renowned Impressionist and Post-Impressionist artists— Monet, Renoir, Gauguin, Cézanne — as well as some of Duchamp’s most notable contemporaries: Picasso, Kandinsky, Léger, Miro, Magritte, Ernst, and Giacometti, the majority of which fared well in an evening of heavy bidding (the Giacometti sculpture, for example, sold for over 14 million dollars).

For Duchamp, context is everything. A shovel in a hardware store is, after all, only a shovel; place it into a museum, and it is magically transformed into art. This is a concept that most collectors of classic European modernism would either fail to understand or flatly reject. Most collectors of contemporary art, on the other hand, accept the philosophical and aesthetic implications of the readymade as an important if not critical precedent to the underlying conceptual strategies of modernism (which, in part, explains Sotheby’s success in sellingFountain for a record-breaking price).

The lesson of placing Duchamp’s work within the context of vanguard art is one that was well understood by the organizers of a sale on May 13, 2002, of Contemporary Art at Phillips de Pury & Luxembourg in New York. The auction featured all fourteen of the readymades that had been issued by the Galleria Schwarz in 1964, these examples from the collection of Arturo Schwarz himself. The sale also included sculpture by Dan Flavin, Donald Judd, Carl Andre, Joseph Beuys, Jeff Koons, Rachel Whiteread, and Maurizio Catelan; photographs by Cindy Sherman, Andreas Gursky, Thomas Struth and Thomas Ruff; paintings by Francis Bacon, Joan Mitchell, Agnes Martin, Gerhard Richter, Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Damien Hirst, Neo Rauch, and Ed Ruscha, whose untitled 1963 painting of the word “NOISE” in yellow against a dark blue ground graced the cover of the lavish, oversized catalogue (Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel appeared on the back cover: Figs. 10.1 and 10.2).

click images to enlarge

- Contemporary Art &

14 Duchamp Readymades,

Phillips de Pury &

Luxembourg,New York, May 13,

2002, catalogue (cover).

- Contemporary Art & 14

Duchamp Readymades,

Phillips de Pury &

Luxembourg, New York, May 13,

2002, catalogue (back cover:

reproduced: Marcel Duchamp,

Bicycle Wheel,

assisted readymade: bicycle

wheel and fork mounted upside

down on a kitchen stool painted

white, 49 13/16 x 24 13/16

x 10 ¾ in.(126.5 x 63 x 27.3 cm).

The sale was accompanied by as much advance publicity as the auction house could muster, including a regular run of advertisements in the New York Times reproducing the various readymades. The only newspaper to run a feature article about the sale, however, was the London Daily Telegraph. The Bicycle Wheel was reproduced, and the article was given the amusing title “Wheel of Fortune,” for as its author Colin Gleadell remarked, it was “estimated to sell for up to $3 million.” Gleadell also informed his readers that in contrast to the issuing of readymades in 1964, which were designed to be sold intact (as complete sets), these fourteen examples were being offered individually, so that collectors were at liberty to chose whichever one they wanted and could afford. He reminded readers that Fountain had sold a few years earlier for $1.7 million, and that, although this information could not be confirmed, an example of the Bicycle Wheel had “sold for more than $2 million on the private market.” Moreover, when the evaluation assigned to all fourteen readymades is tallied, “the overall pre-sale estimate for the set is $8.5 million to $12.6 million,” which, we are told, falls short of the $15 million guarantee Schwarz was given. “Clearly Phillips has taken a gamble,” Gleadell concluded, “one that Duchamp, who had a weakness for risk-taking when playing chess, might have enjoyed.”

In fact, Duchamp took few risks when playing chess, and, as I demonstrate in the first part of this article (Art in America, April 2003), even fewer when it came to his art dealings, whether pertaining to the sale of his own work, or to the investments he had made in the work of others. In the case of the Phillips auction, however, the owners and administrators did undertake a fairly serious financial risk, for it was later revealed that they issued Schwarz a guarantee of $10 million, an amount that fell in the middle of the low and high estimates. If the readymades sold for the low estimate of $8.5 million, the auction house stood to lose $1.5 million; if they sold for their high estimate, they would have made $2.5 million. Apparently, this was a risk the auction house was willing to take, drawing a certain degree of confidence, perhaps, in their recollection of the successful sale of Fountain two years earlier in a sale of Contemporary Art at Sotheby’s.

On the evening of the sale at Phillips, it was raining steadily in New York, which, we can only imagine, must have filled the auctioneers with trepidation, for they knew that if they were to meet their guarantee, they would need as many potential bidders to compete against one another as possible. The eighty-one year old Schwarz, however, who came from his home in Milan to attend the sale, appeared confident and relaxed. Just before the bidding began, a collector asked him if he was nervous. “Why should I be nervous?” Schwarz responded. “As far as I am concerned, they have already been sold.

The sale began with Duchamp’s Paris Air, one of the smallest and least known of the readymades, which was given an estimate of $200,000 – $300,000. Bidding was slow and halting. It eventually stopped at a hammer price of $150,000, short of the low estimate but still higher than the reserve, for, to everyone’s surprise (probably even the successful bidders), the auctioneer announced that the work had been sold. A similar pattern continued for the remaining thirteen readymades, where, in most cases, prices only reached approximately half the low estimates, yet were repeatedly announced as having been sold. Only the Bottle Rack (estimated at $800,000-$1.2 million) and snow shovel (estimated at $700,000-$900,000) failed to meet their reserves. Fountain, which was given a conservative estimate of $1.5 – $2 million (a range that reflected the price it had attained two years earlier at Sotheby’s), sold for a hammer price of just over $1 million, still nearly one-half million dollars short of its low estimate. When the bidding stopped, a quick tally showed that the entire set of readymades sold for $5,370,000, exactly $4,630,000 short of the amount Schwarz was guaranteed, a substantial loss for the auction house, but a huge gain for Schwarz, who, in all likelihood, with a fat check in his pocket, scurried back to Milan the next morning.

By contrast, the rest of the auction went rather well: eight artists had achieved record prices for their work, including the Ruscha cover-lot painting, which sold for over $2.5 million, and a Judd sculpture, which sold for over $1.3 million. The entire auction fetched $29,686,350, with 91% of the offerings sold by value. In a report issued by the auction house after the sale, these facts were of course emphasized, and in an effort to put a positive spin on the sale of readymades, it was even announced that Duchamp’s “iconic Bicycle Wheel tied the record for any Readymade,” which it did, since it sold for the same price as Fountain two years earlier at Sotheby’s. Of course, there was no mention of the fact that Phillips lost over $4.5 million on its guarantee to Schwarz, which was perceived by many to have been a total disaster for the Duchamp market

Perception is, of course, only a reflection of the person doing the perceiving. In describing the sale of the readymades in her regular column for the New York Times, Carol Vogel reported that “collectors sniffed at what some consider icons of modern art,” and Christopher Michaud, writing for the Reuters News Agency, reported that the prices of the readymades “fell far short of expectations, eclipsed by works of more current artists.” Josh Baer summarized the evening best when he wrote in his newsletter that “people will look back on [the sale] and wish they had bought.

So far as the sale of Duchamp’s work is concerned, the failure of the readymades to attain their estimates may inhibit sales in the short term, but in the future, there will be little — if any — harm done to the general Duchamp market. To my way of seeing things, there are two reasons why Duchamp’s work continues to be assigned comparatively low evaluations: rarity, and, perhaps even more importantly, an unrelenting cerebral content.

Rarity is a factor that in most commercial markets causes an item gradually to escalate in value over time. Precisely the opposite occurs in Duchamp’s work, for its rarity creates a situation in which reliable evaluations of comparable prior sales cannot be established. The best way to demonstrate this point is by citing a hypothetical example: Say that you own a work of art by a notable artist that you are interested in selling. When an attempt is made to evaluate the work, comparables are cited, earlier examples by the same artist from the same period that have sold — either at auction or privately — within the recent past (in the art market, up to five years is usually considered a fair indicator). If you should manage to find a comparable work that sold for X-number of dollars, naturally you want the work of art that you own to be evaluated at a somewhat higher figure, an amount that reflects the time passed since the comparable work was sold. When it comes to unique works by Duchamp, however, there are preciously few comparables. During his lifetime, he saw to it that his most important work was placed into important private collections (such as with Arensberg or Dreier), which he knew would one day be donated to museums.In the Duchamp market, then, the “snowball effect” that causes works of art to escalate in value over time is virtually nonexistent. As a result, one can ask whatever one wants for a unique work by Duchamp, but even here, the price must remain within reason, that is to say, controlled by some knowledge of prices that were paid for other works by artist in the comparatively recent past.

click to enlarge

Figure 11

Figure 11

Marcel Duchamp, Belle Haleine:

Eau de Voilette (Beautiful

Breath: Veil Water),

1921, assisted Readymade,

perfume bottle (6 in.) in cadrdboard

box, 6 7/16 x 4 7/16 in..

Figure 12

Marcel Duchamp, L.H.O.O.Q.

, 1919,7 ¾ x 4 7/8 in.

Today, the most common way to the check prices paid for an individual artist’s work is on the Internet. A variety of sites offer postings of recent auction records, but it is virtually impossible to find any verifiable information pertaining to private sales. Of course, when a collector of means is matched with a work of art that he or she absolutely cannot live without, the question of comparable evaluations is of no relevance. In the André Breton sale that took place recently in Paris, for example, the Monte Carlo Bondsold to the Principality of Monaco for 240,000 euros (well above its pre-auction estimate of 50,000 to 60,000 euros). A similar situation occurred in the mid-1990s, when a collector and former art dealer living in Paris sold Duchamp’s Belle Haleine (Fig. 11) perfume bottle to Yves Saint-Laurent and Pierre Bergé for five million dollars. The collector originally purchased the work some twenty-five years earlier from the Forcade-Droll Gallery in New York, and, at the same time, he also purchased the original L.H.O.O.Q. (Fig. 12), which is still in his collection. Some years ago I was approached by a curator at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, asking whether I knew if this work could be acquired. I called the collector in Paris and asked if he would consider selling it. He responded to my inquiry by asking if I knew the highest price ever paid for a work of art. Recalling Renoir’s Moulin de la Galette, I said that I thought it was around 65 million dollars (having forgotten that a van Gogh sold a few years later for some 20 million more). He said: “Bring me a collector willing to pay 66 million dollars, and we’ll talk.

Even if the information pertaining to private sales were made public, I doubt that it would affect the comparatively depressed financial evaluation given to works by Duchamp. This, I believe, can be traced to a single overriding factor: the importance of vision over thought. Unlike more traditional works of art, which rely primarily upon visual comprehension for understanding their importance — and, thus, financial value — a work by Duchamp (particularly the readymades) relies upon more complicated processes of thought. We can look at a painting by Matisse, for example, and appreciate it on a purely visual level. Indeed, Matisse himself encouraged precisely this method of viewing when he stated that “an art of balance, of purity and serenity” is “something like a good armchair that provides relaxation from fatigue.”By contrast, any viewer who looked at Duchamp’s readymades in this same fashion would derive little or no aesthetic pleasure; no matter how long you look at a shovel — whether hanging in a museum or in a hardware store — it remains a shovel. In this case, viewers are forced to echo a strategy employed by the artist himself when selecting these objects, for he wanted the readymades to exhibit no exceptional visual interest, or, as he said, they are objects possessed of “visual indifference… a total absence of good or bad taste… a complete anesthesia.”

If we apply this reasoning to the marketplace, then an art dealer or seller is placed in a somewhat unusual position. He or she can no longer present a work of art to his or her client and allow a purely visual response to convey its content. I have come to refer to this predicament as the triangle theory, where, under normal circumstances, three specific points must be identified and understood before a sale can take place: (1) the client’s eyes; (2) the work of art; (3) the client’s pocketbook. In trying to sell a work by Duchamp, one point in this triangle must be adjusted slightly, for in considering a readymade, one cannot rely solely upon a client’s vision. Instead, the seller is obligated to move that point one or two inches back, to a position well with the client’s gray matter. Only then can he hope to come anywhere near the client’s pocketbook. If the person’s intellect is not stimulated, then, as in the case of looking at a readymade like Duchamp’s In Advance of a Broken Arm, a shovel remains a shovel, which in most hardware stores sells for about fifty dollars (not $600,000, which is the amount for which this item reportedly sold in a private sale to a European client a few days after the Phillips sale).

It is my belief that, in the future, works of art will be increasingly appreciated for their cerebral content, although for the present moment, at least, vision is still required to comprehend the existence of the object. At this point in time, we can only imagine a work of art that would stimulate our minds before reaching our eyes (of course, the same could be said for all kinds of social situations, from race relations to geographic borders, as in John Lennon’s use of the word “Imagine”). Meanwhile, as was his habit, Duchamp seems to have timed things perfectly: if there is any correlation between the aesthetic value of a work of art and the amount of money that someone is willing to pay for it, at the very moment in our history when intellect and vision strive to achieve union, there are virtually no important works by Duchamp available to test the market. He was not only successful in thwarting attempts to commercialize his work in his lifetime. In having kept his production of unique works of art to a minimum, only replicas and works in edition remain within the marketplace today, and even these items come up only rarely. Some thirty-five years after his death — in both aesthetic and monetary terms — Duchamp remains securely one step ahead of the game.

Notes

1. Quoted in a letter to the author from Diana Nemiroff, Curator of Modern Art, National Gallery of Canada, 25 September 2002.

2. Information provided in an email message to the author dated October 14, 2002, from Nan Esseck Brewer, Curator of Works on Paper at the Art Museum of the University of Indiana at Bloomington. Additional details concerning the purchase was relayed to the author in a telephone conversation with Thomas T. Solley from his home in England on October 15, 2002.

3.It should be acknowledged that I was among those who negotiated to acquire these works, eventually acquiring the Network of Stoppages (now collection of the Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven),Bottle Rack, In Advance of a Broken Arm, Fountain,

and Fresh Widow (the latter four now in the collection of the Maillol Foundation, Paris).

4.Quoted in Carol Vogel, “More Records for Contemporary Art,” The New York Times, November 18, 1999.

5. See Jeffrey Deitch, ed., The Dakis Joannou Collection (Ostfildern: Cantz, 1996), p. 93.

6.At the time when this essay was written, I had mistakenly concluded that no. 4/8 of the edition was in the collection of the Toyama Museum of Art in Japan.That information proved incorrect, for no. 4 of the edition appeared on the market in 2002 at the Gagosian Gallery in New York (with a provenance that can be traced to Sarenco & Sarenco of Milan, Italy).

7.The friend, Nura Petrov, is an artist who lives in Riegelsville, Pennsylvania.

8.The Duchamp show was entitled “Marcel Duchamp: The Art of Making Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” and was held at Achim Moeller Fine Art, New York, 2 October 1999 — 15 January 2000.

9.Colin Gleadell, “Wheel of Fortune,” The Daily Telegraph [London], April 22, 2002. I am grateful to the author, who kindly provided me with a photocopy of his article.

10.The collector wishes to remain anonymous.

11.“Phillips, de Pury & Luxembourg Set 8 Artist Records in $29 Million Sale of Contemporary Art on May 13, 2002,” Click here to view the link.

12.Josh Baer, The Baer Faxt # 318, May 13, 2002; Christopher Michaud, “Rare Duchamps Collection Sold at N.Y. Auction,” Reuters Press, May 21, 2002; Carol Vogel, “An Uneven Night at Auction for Phillips,” New York Times, May 14, 2002. See also Brooks

Barnes, “Phillips Contemporary Art Auction Brings in a Healthy $30 Million,” The Wall Street Journal, May 14, 2002.

13.When he served as executor of Dreier’s estate, he arranged for several of his most important works to be placed into the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art, which demonstrates that, in some measure, he wanted his work to be seen and understood

within the context of a larger, more international audience.

14.The collector wishes to remain anonymous, and even though he has refused to confirm the sale price of the Belle Haleine,its current owners requested an insurance evaluation of five million dollars when they lent the work to a show I organized for the Whitney Museum in 1996 (see the catalogue, Making Mischief: Dada Invades New York, Whitney Museum of American Art, distributed by Harry N. Abrams, New York, 1996, pp. 146 and 292).

15.Henri Matisse, “Notes of a Painter,” 1908; quoted in Alfred H. Barr, Jr., Matisse: His Art and His Public (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1951), p. 122.

16.“Apropos of ‘Readymades’,” a talk delivered by Duchamp at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 19 October 1961; published in Art and Artists,vol. I, no. 4 (July 1966), p. 47.

Figs. 6-8, 11-12 ©2003 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris. All rights reserved.

1. Translator’s Note: this is an untranslatable play on words that hinges on the homophonic double meaning of “faucon” (falcon) and “faux con” (false cunt). For further discussion of this pun, see Craig Adcock’s “Falcon” or “Perroquet”? in http://www.toutfait.com/duchamp.jsp?postid=773&keyword=

1. Translator’s Note: this is an untranslatable play on words that hinges on the homophonic double meaning of “faucon” (falcon) and “faux con” (false cunt). For further discussion of this pun, see Craig Adcock’s “Falcon” or “Perroquet”? in http://www.toutfait.com/duchamp.jsp?postid=773&keyword= 2.Poèmes à Lou, “A mon tiercelet,” LXI.

2.Poèmes à Lou, “A mon tiercelet,” LXI. 3.Unpublished note from the assembly notebook for Étant donnés,

3.Unpublished note from the assembly notebook for Étant donnés, 4.In a letter to Louise and Walter Arensburg dated July 22, 1951 Naumann, Francis M. and Hector Obalk Ludion, eds. Affectionately,Marcel (Ghent-Amsterdam: Ludion Press, 2000) 302-303..

4.In a letter to Louise and Walter Arensburg dated July 22, 1951 Naumann, Francis M. and Hector Obalk Ludion, eds. Affectionately,Marcel (Ghent-Amsterdam: Ludion Press, 2000) 302-303.. 5.It is known that she is made from a pig skin.

5.It is known that she is made from a pig skin. 6.My gratitude goes to Pontus Hulten for having led me toward this interpretation.

6.My gratitude goes to Pontus Hulten for having led me toward this interpretation. 7. Let us remember here this note from À l’infinitif: “By mold is meant: from the point of view of form and color, the negative (photographic); from the point of view of mass, a plane (generating the object’s form by means of elementary parallelism).”Sanouillet, Michel and Elmer Peterson, eds. The Writings of MarcelDuchamp (New York: Da Capo Press, 1973) 85.

7. Let us remember here this note from À l’infinitif: “By mold is meant: from the point of view of form and color, the negative (photographic); from the point of view of mass, a plane (generating the object’s form by means of elementary parallelism).”Sanouillet, Michel and Elmer Peterson, eds. The Writings of MarcelDuchamp (New York: Da Capo Press, 1973) 85. 8. In Thalassa, Psychanalyse des origines de

8. In Thalassa, Psychanalyse des origines de 9. My gratitude, here, to Jacqueline Pierre, biologist,

9. My gratitude, here, to Jacqueline Pierre, biologist, 10. Sanouillet, Michel and Elmer Peterson, eds. The Writings of Marcel Duchamp (New York: Da Capo Press, 1973) 29.

10. Sanouillet, Michel and Elmer Peterson, eds. The Writings of Marcel Duchamp (New York: Da Capo Press, 1973) 29.  11.Account given by François Le Lionnais, October 1976.

11.Account given by François Le Lionnais, October 1976.  12.In Les Quatre Concepts fondamenteux de la psychanalyse (Paris,1973) 65-84.

12.In Les Quatre Concepts fondamenteux de la psychanalyse (Paris,1973) 65-84.  13.Op. cit., “La schize de l’œil et du regard,” p.71.

13.Op. cit., “La schize de l’œil et du regard,” p.71. 14. Connecting Étant donnés to the myth of Artemis

14. Connecting Étant donnés to the myth of Artemis