In the conclusion of my article for the fourth issue of Tout-Fait Journal , I identified a possible theme in the artistic events of the 1900’s. I’m referring to the gradual emergence, in art, of important ideas and conceptual themes which also belong to the grounding kernel of the complexity sciences.

As a first step, my concern was (and still is) to illuminate some unexpected links, all of them directly related to some fundamental ideas of complexity, between some leading figures in twentieth century art, namely Klee, Duchamp and Escher. This unexpected relationship is even more surprising considering the radical differences between their personalities and their artistic results, or at least the retinal (to use a duchampian term) ones. Furthermore, as far as I know, there is nothing in their writings that links these artists. Relations between Duchamp, Klee and Escher cover a huge range of ideas, and the complexity sciencesprovides us with a realm in which we can unify them.

At the yearly conference “Matematica e Cultura” in Venice , organized by Prof. Michele Emmer, I gave a talk titled “Strands of complexity in art: Klee, Duchamp and Escher”, where I presented some preliminary findings of my research. This article supplements those preliminary findings with new analogies. I’ll start by summarizing those first ideas; and then I’ll introduce other subjects, such as evolution, topology, impossible 3D objects and enlarged conceptions of perspective. Finally I’ll try to relate these themes with those of complexity.

1. A summary of preliminary findings

I divided the common traits between Klee, Duchamp and Escher into three groups, all of them mathematically relevant and strictly related to each other and to corresponding complexity themes. They are:

a. Recursion and fractals

b. Feedback loops and self organization

c. Instability and chaos

(Particularly for the a. and b. points, I took the most part of my argument about Duchamp from my article on Tout-Fait Journal cited above, where the reader can find some detailed explanations about the subjects summarized below).

a.

In Escher’s work the role of recursion, and the presence of fractal structures have been well known and accepted since the appearance of Hofstadter’s classic book .

As far as Duchamp is concerned, recursive structures underlie not only several individual works, but also creative processes on a larger scale, involving several works at once. I also suggested the presence (at least in embryonic form) of the idea of fractal structures, mainly linked to the typical duchampian procedure of repetition on a lower (reduced) scale.

Much of Klees work is based on recursive (iterative) procedures. Klee called themprogressions. They are mainly related to natural processes. In relation to natural processes Klee’s intuition of abstract mathematical concepts, like fractal dimensions (ie non-integer dimension), is notable, especially in relation to the botanical world.

b.

click to enlarge

Figure 1

Marcel Duchamp, The Bride

Stripped Bare by Her

Bachelors, Even, 1915-23

Here Escher’s use of tessellation comes to mind. A game of symmetries could be seen as a complex system, where very simple rules (namely the given symmetries) exert their reciprocal feedback locally; as well as interacting to have dramatic, global and complex consequences on the whole tiling system. This can be (meaningfully) related to concepts regarding morphogenesis: simple rules can create global complexity, provided that the components of the system are sufficiently connected to each other.

In most of Klee’s works we can see feedback loops in action, both negative and positive. True dynamic systems are the results of these loops. Klee relates them to morphogenetic processes. Once again, the key point is: local simplicity coupled with a huge network of connections) can determine the emergence of global organizational patterns.

Several of Duchamp’s wordplays show self-organizing properties. In a broader sense there are similar random self-organizing processes acting in the Glass. (Fig. 1)

c.

Looking at Escher’s prints, exposure to conflicting stimuli (such as black-white, concave-convex, figure-background) destabilizes the observer. This theme has been already widely discussed by scholars . Also, Escher is particularly interested in whirling structures that draw together self-reference, fractal structures and whirling, chaotic motions.

click to enlarge

Figure 2

Marcel Duchamp, The Bride

Stripped Bare by Her

Bachelors Even [The

Green Box], 1934

It is well known that instability plays a key role in Klee’s compositions. Moreover Klee was attracted by what nowadays is called deterministic chaos, ie. unpredictable, irregular behavior, rising from the iterations of simple deterministic procedures. A number of different figurative frameworks are borne out of iterative procedures that have been triggered to behave irregularly. The most interesting thing, however, is that from such quite chaotic tangles of lines, often perfect vital and shiny forms emerge. An interesting analogy can be drawn here with the edge-of-chaos idea of complexity.

Instability and chaos are quite typical duchampian themes. His wordplays depend on predetermined lexical conditions; the slightest differences in either a single syllable or letter or even simply intonation could cause radical shifting in the meaning of a sentence (here we have a true sensitive dependence on initial conditions). Furthermore, Duchamp saw the creative power of instability. In the loosest sense it could be seen everywhere in the Glass and in theNotes of the Green Box, (Fig. 2)but more specifically we see that in the works based on rotatory motion, where highly unsplanar sets of rotating circles can create the illusion of the sthird dimension. Here again the creative power of instability has been exploited which is also powerful edge-of-chaos idea.

2. Evolving systems

Before the twentieth century it was physics, not biology, that was the leading area of scientific endeavour. It was from physics that models and protocols for science were drawn. The 1900s saw a shift towards biology. This shift was consistent with the progressive affirmation of the new paradigm of complexity.

This interest in biology is reflected in the work of Klee, Duchamp and Escher. Firstly Klee, whose interest in Natural History (especially in botany) is well known; like a naturalist he focused (as both artist and teacher) on the central problem of organic growth. He investigated both morphology (the study of forms) and morphogenesis (the study of processes leading to form); his intuitive, biological investigations are notable.

Escher, for his part, was more attracted by abstract ideas; more mathematical than biological, but was nonetheless intrigued by the natural world. He dealt especially with the inanimate world of minerals and crystals. However biologists drew analogies of his abstract ideas with corresponding biological concepts; sometimes Escher dealt with biological processes themselves.

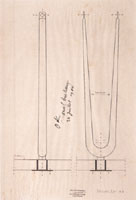

click to enlarge

Figure 3

Marcel Duchamp,Bride’s

Domain from the Large

Glass, 1915-23

Figure 4

Marcel Duchamp,Bachelor

Apparatus from the Large

Glass, 1915-23

Perhaps Duchamp is the artist who best expressed (both in advance and inadvertently) the inversion of the relationship between biology and physics: by distendingthe laws of physics and chemistry he bypassed the rigid determinism and the reductionism of those disciplines. By grafting the organic forms of the Bride (in the higher part of the Glass) (Fig. 3) onto the mechanical machinery of the Bachelors (in the lower part) (Fig. 4)Duchamp not only expressed the idea of a marriage between physics and chemistry (at the bottom, in a three dimensional world), and biology, (above, in a four dimensional world) but perhaps even the superiority of the latter: after all the bride is queen.

This new kind of interest in biology is related to the development in every scientific field of systemic theories. This began in the 1940’s with cybernetics and ended up with the establishment of complexity sciences: what better paradigm of a system is there than an organism? Biology teaches us that complex systems adapt and evolve, we call them complex adaptive systems (CAS) Adaptation and evolution are key in all areas of the complexity sciences. Can artists, that were aware of world-system complexity, have been unaware of these notions of adaptation and evolution, at least at some intuitive level? In my opinion no. Being sensitive to complexity implies having some awareness of evolutionary processes (not necessarily biological), driven by random probabilistic events coupled with adaptation, which make the world-system ever changing.

In Klees’ writings we find a number of references to evolutionary biology . He clearly had some understanding of the subject matter. However, it is what he did as a painter, more than what he thought as a naturalist, that is interesting here.

He would lovingly cultivate mistakes he made, and embed them in his paintings. He would encourage pupils to draw with their left hand, and to nurture the irregularities that ensued. He also would introduce subtle and repeated variations into his work that would form mobile, ever changing patterns. Klee clearly loved chance.

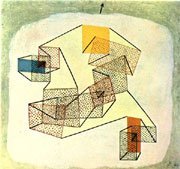

click to enlarge

Figure 5 Paul Klee, Red fugue,1921

Figure 6 Paul Klee, Sheet from the

town book, 1928

Here, two of Klees’ groups of work are of note: those of Red fugue (1921) (Fig. 5) andSheet from the town book (1928) (Fig. 6). Both groups are based on repetitive horizontal sequences, which are gradually transformed by introducing constant, apparently random variation in the repetitions of the starting shape. The representation of an evolutionary process could be seen in these paintings, where random mutations seem to be somehow selected to obtain certain properties of the resulting patterns. I discussed the subject in some detail in the article already cited , and I showed by means of computer simulations that evolutionary algorithms can produce quite similar patterns.

Let us consider now Escher’s use of tessellation or tiling (i.e. covering of the surface by means of repeated tiles, without empty gaps and overlapping), such as the one signed E15(1938) (Fig. 7). Each single piece of tiling contains the complete information necessary to build the whole surface; of course this holds.

click to enlarge

Figure 7

M.C. Escher, E15, 1938

Figure 8

M.C. Escher, Metamorphosis, late 1930s

Figure 9

M.C. Escher, Verbum, 1942

Meaningful analogies with the idea of complete genetic information contained within each cell of an organism. Parallels between Escher’s tessellation and mechanisms in biochemistry have been developed by Edward Whitehead .

Interestingly, Escher’s tiling often depicts a process which gradually transforms the structure of the tiles. This transformation is rendered infinite by the introduction of a circular narrative pattern, which leads it back to its starting point. The strips namedMetamorphosis (the process which turns the larva into insect) are examples of this (Fig. 8) which Escher created in the late 30’s. Such transformation can be seen to some extent as a metaphor for evolutionary process. This, at least, was the opinion of Nobel chemist Melvin Calvin on Escher’sVerbum (1942) (Fig. 9) .

Let us thirdly consider Duchamp.

The theme of the dichotomy mother – egg, and the paradoxes that lie therein are worthy of investigation. I discussed the subject in the already cited article .

Duchamp used objects and moulds to signify the idea of mother and egg. The mould represents the egg, the object the mother. He used these in a number of different contexts, including the Malic Moulds of the Glass. (Fig. 10)The object and the mould are self-perpetuating and codependent : the object is used to cast the mould and the mould to shape the object. Similar ideas are identifiable in Three Standard Stoppages (1913-14) (Fig. 11)and Tu m’ (1918) (Fig. 12). For the latter he made three wooden templates, for transferring the outline of the threads contained in the Stoppages onto the oil painting. In Tu m’ these templates appear again, depicted in the bottom-left corner; their respective threads in the right hand corner. We have the old threads; their templates, and the new threads… The two elements (thread-Mother and template-Egg) are present in both the Stoppages and Tu m’. (En passant: notice that in Tu m’ the representations of templates and threads stand at the opposite sides of the picture, as we said above; in the middle, the psychological epopee of Bride and Bachelor is abridged, maybe as the necessary step to link egg and offspring).

Figure 10 Marcel Duchamp,

Nine Malic Molds,1914-15

Figure 11 Marcel Duchamp,

Three Standard Stoppages,1913

Figure 12

Marcel Duchamp,Tu m’, 1918

Now the key question is: is this chain deterministic? Could this cyclic process repeat itself unchanged, giving rise to ever equal objects? It couldn’t. Indeed, remember that Duchamp explicitly connects the idea of mould with the idea of infra-thin difference:

click to enlarge

Figure 13

Marcel Duchamp,

Cemetery of Uniforms and Liveries, No. 2, 1914

Infra-thin separation. 2 forms cast in the same mould (?) differ from each other by an infra thin separative amount. All “identical” as identical as they can be, (and the more identical they are) move toward this infra thin separative difference. (Note posthume).

Thus the process contains an important random event (possibly corresponding to biological mutation). A parallel could be drawn between evolutionary process and the cyclical alternation of the object and the mould(Mother-Egg). At the very least, this observation would be consistent with Shearer’s idea that the cemetery of liveries (Fig. 13)(the Malic Moulds) could be seen as the place where scientific knowledge is recorded . An empty livery is a repository for a scientific idea as well as being a mould that produces new ideas on which are encoded new theories, thence new liveries and so on.

3. Topology

click to enlarge

Figure 14

M. C. Escher, Moebius band I, 1961

Figure 15

M. C. Escher, Moebius band II, 1963

click to enlarge

Animation 1

Animation of Moebius Strips

Klee, Duchamp and Escher were all three attracted by topologically interesting figures.

Several of Escher’s works deal with topological figures, such as knots (Knots, 1965) and Moebiusstrips (as in Moebius band I, 1961 (Fig. 14) andMoebius band II, 1963 (Fig. 15)).

Moebius strips (see Animation 1 which explains a possible genesis of the strip starting from a cylinder) exhibit a number of interesting properties; I’ll recall and briefly explain some of them.

First, unlike the cylinder, which has both an internal and external surface, the Moebius strip has only one surface; This can be easily verified by mentally painting its whole surface, without lifting the brush from the strip.

Second, whilst a cylinder has two edges (lower and higher) the Moebius strip has one only edge; once again you can follow this edge completely with the finger without having to lift it from the edge.

Furthermore, if one cuts the cylinder longitudinally, two distinct cylinders will be obtained, whereas by cutting the Moebius strip the same way, one only new strip is yielded.

Escher carefully showed these properties in his prints. In Moebius band I he cut the strip longitudinally and obtained three snakes eating each other’s tail, while in Moebius band IInine ants in line walk on the strip, so as to highlight the single edge and single face concepts.

Escher was interested in the circularity of his knots and strips. He drew them together in a monograph under the chapter heading spatial circles and spirals. His knots, Moebius strips, as well as planar and spherical spirals, were all drawn together in this section. The knots follow circular pathways which end up at the starting point after torsions and self-intersections. The same holds for the Moebius strips.

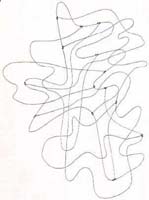

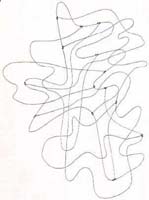

Klee too, was interested in knots, and had been since childhood. Several of his early drawings show knotted worms hanging from a fisherman’s hook. We see the same worms, now abstract knots, in later drawings such as Ways Toward the Knot (1930) (Fig. 16). 2D knots are also drawn according to even more essential forms, like the infinity-shaped motif (and its polygonal variants) shown in his pedagogical sketch (see Sketch 1). We see a huge collection of similar patterns in pictures like Dynamically polyphonic group (1931) (Fig. 17), which is based on a feature of those 2D knots Klee was interested in (see Animation 2): a hatch follows the course of the knot with continuity, but always remaining on the same side of the line; in so doing, the hatch highlights the inside of one half of the motif, and the outside of the other half. How is it possible to pass from inside to outside, while remaining on the same side of the line? It is due to the self-intersection of the 2D knot (corresponding with the torsion in the Moebius strip), which allows passage from an inner to an outer region, without passing from one side of the line to the other. As we saw before, Moebius strip has a similar property. Let us return to Klee’s 2D knots. He amplified them, to form complex, perpetual pathways, once again formed by uninterrupted, closed, self-intersecting lines (often polygonal instead of curved) and always returning to the starting point. This is typical of Klee’s drawings of the late 20’s and the early 30’s. An example is the drawingMechanics of an Urban Area (1928) (Fig. 18).

Animation 2

Animation based on the 2-D knots

Figure 18

Paul klee, Mechanics of an Urban Area, 1928

click to enlarge

Figure 19

Paul Klee, Excited, 1934

Sketch 2

Folding recursive process

We have other evidence of the special topological meaning of Klee’s images, such as labyrinths. Labyrinthine lines and signs are indeed among the most important patterns in Klee’s late style. Several hypotheses could be made to explain the genesis of such patterns, and in my opinion they are often linked to morphogenetic processes . There are, however, some drawings, such as Excited (1934) (Fig. 19) and all the others, based on the same framework, which particularly show the underlying presence of the folding recursive process (seeSketch 2). Similar (but reversed) processes are sometime used for classifying labyrinths in topology unrolling them, to obtain the simpler equivalent form. But, interestingly, similar folding processes can also give rise to fractal and/or chaotic structures which in turn can be connected with the corresponding themes highlighted above.

With reference to the use of Duchamp’s topological figures, I have already underlined the importance of the Kleinian bottle, along with some related Moebius-strip-like structures in his writings and works , and I have already stressed a possible meaning of this circular self-penetrating and self-encompassing figure, this is recommended further reading.

Now I’ll focus on further interesting links between Klee, Escher and Duchamp with respect to the use they made of the well-known topological properties of those surfaces. The analogy between the infinity-shaped motif of Klees’ and Eschers’ Moebius strips is further reinforced by observing some other prints of Escher’s, which came 10 or 15 years before his Moebius strips; Horsemen (1946) (Fig. 20) and Predestination (1951) (Fig. 21)show the planar infinity-shaped motif.

Let us take Duchamp’s Steeplechase (Fig. 22): it is a self-made racing course, for a childish horserace game in which there is a clear connection with both Klee’s infinity-shaped motif and Escher’s prints Horseman and Predestination. This could be seen as an antecedent ofSculpture for Travelling (1918). (Fig. 23)

click to enlarge

Figure 20

M.C. Escher, Horsemen, 1946

Figure 21

M.C. Escher,

Predestination, 1951

click to enlarge

Figure 22

Marcel Duchamp, Steeple-chase

cloth,ca. 1910

Figure 23

Marcel Duchamp, Sculpture

for Travelling, 1918

Jean Clair suggested an interesting analogy between the kleinian bottle and some alchemic symbols, such as the one of the pelican devouring itself, and then he connected it with Duchamp’s Air de Paris (Fig. 24). Look now at Escher’s preparatory sketch (Sketch 3)of a Pelican; although in the definitive print he substituted the pelican with a dragon (Dragon, 1952) (Fig. 25), he maintained however the same idea of a self-penetrating and self-eating animal (after all, the snakes eating each other’s tail in Moebius band I refer to the same theme). As far as Klee is concerned, we saw similar self-eating structures, though abstract, in the meandering lines of the drawings around 1934, use the same techniques as the previously mentioned Excited: the basic motif (see Sketch 4) is formed by two curves penetrating one another, the end of the one into the belly of the other.

Figure 24

Marcel Duchamp, Air de Paris, 1919

Figure 25

M. C. Escher, Dragon, 1952

Sketch 3

M. C. Escher, preparatory sketch of a Pelican

Sketch 4

Two curves penetrating one another

In his latest style Klee used a typical pattern whose genesis and meaning we can better understand by looking at a detail of the drawing The fugitive is Looking Back (1939) (Fig. 26); the body of the fugitive is based on branching curved lines, the one starting from the back of another. The head too is formed by a similar, curved line, but it is branching from its own back, in a circular, self-referential scheme. This motif is further amplified in innumerable drawings and paintings around 1939-40, where we find a lot of self-embedded, self-encompassed figures, such as in Fastening (1939) (Fig. 27).

Figure 26

Paul Klee, The fugitive

is Looking Back, 1939

Figure 27

Paul Klee, Fastening,1939

What is the significance of this trend for using topological figures? What relationship can we establish between that and complexity?

First, with Klee, Duchamp and Escher there is a tendency to represent very complex things, where the parts are widely connected to each other, interacting with non-linear pathways, often looping and returning to some crucial points. Thus the tangled intricacy of some knots or labyrinths visually and effectively expresses the corresponding intricacy of the components of their complex systems.

Second, such intricacy of connections within a system often produces unexpected outcomes, which in turn imply new unexpected outcomes, and so on. Thus in the complex system represented in their works by our artists, it is difficult to discern clearly causes and effects, because of the network of their reciprocal feedback. The unexpected, often strange and sometimes paradoxical outcomes rising from systems subjected to circular feedback and self-referential loops have corresponded with the strange and paradoxical properties of figures such as knots, the Moebius strip or the Kleinian bottle, due to their circularity, their self-intersections or self-penetrations. The same could be said for those figures discussed above, often used by the late Klee, which are self-encompassing.

Particularly in the case of Duchamp, as I have already shown , the topological properties of the kleinian bottle were used to express the paradoxical identity Egg–Mother (or Bride–Glass). This was discussed in the previous section, and in general to express the autopoetic properties of the duo Glass–Box.

4. Enlarged perspective and Impossible 3D objects

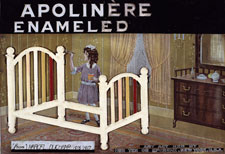

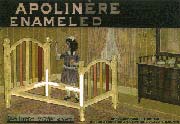

Figure 28

Marcel Duchamp,

Apolinère Enameled, 1916-17

Figure 29

Paul Klee, Chess, 1931

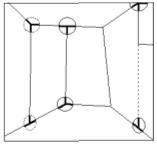

Sketch 5

Trihedral junction

versus DihedralT-junction

Sketch 6

Trihedral

junction versus Dihedral

T-junction in Apolinère Enameled

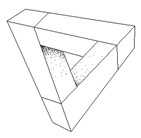

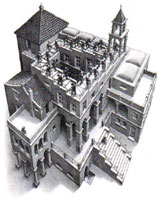

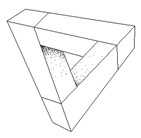

Rhonda Shearer thoroughly discussed the relationship between some of Eschers’ and Duchamps’ works, based on 3D impossible objects. She documented how Duchamp’s Apolinère Enameled(1916-17) (Fig. 28) predates by forty years the seminal paper of Lionel and Roger Penrose on impossible 3D figures . She also stresses the bond of friendship between Duchamp and Roland Penrose, a close relative of Lionel and Roger. The cited Penrose article is the professed source of inspiration of Escher’s famous impossible figures, so that the reading of Shearer’s article cements a direct link between Escher and Duchamp via the Penroses.

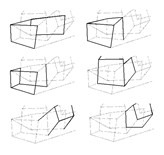

But, what about Klee’s impossible 3D objects? We shall discuss some works, which are representative of corresponding frameworks, all of them developed in about 1930 and deeply linked with one another.

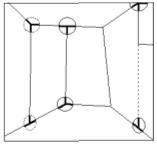

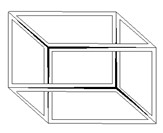

The first we shall consider is Chess (1931) (Fig. 29). I have elsewhere already examined this painting, its genesis and its possible meaning . Here I want only to recall that the bare, empty room in the background is an impossible 3D object (as a matter of fact, many other elements in the painting are spatially inconsistent, but here we shall confine ourselves to the background only).

The walls of the room are joined to each other by means of vertical edges, three of which are explicitly traced, whilst the fourth (the dotted one in Sketch 5) is only suggested by the left side of the paler rectangle in the upper right hand corner of the painting. Three of those vertical edges have mutually inconsistent junctions at the opposite extremities: one end shows a trihedraljunction, where three distinct edges converge, while at the opposite end, two of the three edges line up one another, giving rise to a dihedral T-junction. Thus, the background is an impossible, puzzling 3D object, and the checkerboard covering over the scene may suggest something like a chess problem, just to emphasize the spatial enigma posed by the background.

Look now at Apolinère Enameled: one among the ingredients for making this 3D object impossible, is just the same as for Klee’s Chess: mutually inconsistent ends of a edge, highlighted in Sketch 6.

Klee used to express the concepts and the ideas he was interested in, by means of graphic simplifications, focusing his attention on only the essential parts. He would discard irrelevant and non-essential details, that might mislead the observer and would especially avoid repetition and redundancy. If necessary they wold just suggested.

That’s the reason why we find traces of other impossible 3D objects in a very simplified form; as is the case for The Conqueror (1930) (Fig. 30). Look at his banner. Though a banner is essentially a flat object, at first sight we actually perceive something like a cube, a solid figure; but counting the peripheral sides of the overall silhouette, we find that there are five, not six, as we would generally expect (Sketch 7). Something here is wrong: as soon as we accept the hypothesis of a possible 3D vision, we immediately recognize that it is inconsistent with some details of the motif. There is something missing. To better understand what really is missing, let us examine a further simplified versions of the same motif in another of Klees’ pictures: Six species (1930) (Fig. 31). Look at the flower displayed in Sketch 8. To make it spatially plausible, we have to mentally add a missing edge to form a trihedron; the same holds of course for each other flower in the painting. Without the addition of the missing edge we perceive something oscillating between a dihedron and a trihedron, which leads us back to the analogous ambiguity we saw in Chess.

click to enlarge

Figure 30

Paul Klee, The

Conqueror, 1930

Figure 31

Paul Klee, Six

Species, 1930

click to enlarge

Sketch 7

The impossible 3D object

Sketch 8

An edge is added

to form a trihedron

Notice now that Duchamp was interested in exactly the same ambiguity. Look indeed at the recto side of the Hershey Postcard note (circa 1915) (Fig. 32), or even at the miniature reproduction of Why Not Sneeze Rose Sélavy? in the Boite-en-Valise (1941) (Fig. 33).

click to enlarge

Figure 32

Marcel Duchamp, Note on

Hershey Postcard, circa 1915

Figure 33

Marcel Duchamp,miniature

version of Why Not Sneeze

Rose Sélavy? (1921), in

Boite-en-Valise(1941)

Returning now to Klee’s Conqueror, it is easy to see similar treatments in its banner. Especially in this case, as we said above, the perception oscillates continually between the 2D and 3D: no sooner have we arrived at a 2D hypothesis, then we are pushed to reject it and embrace 3D one, and vice versa. The relevance of some of Duchamp’s and Escher’s ideas is here clear, for it is well-known that the conflict between surface and space is one of the most important among their themes.

Let’s now turn our attention to Klee’s Soaring, Before the Ascension (1930) (Fig. 34) which is representative of several paintings based on the same framework, worked out in the years we are considering. The framework is based on rectangles freely soaring over the whole surface of the work, connected to each other with colored bars.

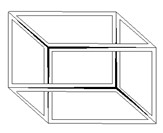

At the first glance we realize that the whole is spatially inconsistent, though the local details are not. Particularly, it happens that focusing our attention on a couple of connected rectangles at once, there is no problem; but considering three or more connected rectangles at once, in the most cases it yields spatial inconsistencies, that prevent the observer from seeing which are the closest or the farthest planes (unless one admits the bars could make a hole in the rectangles and pass through them).

In Soaring Klee used several skewed perspective boxes at once, like the ones in his pedagogical sketch (Sketch 9). Here we are confronted with the desired effect of spatial ambiguity, for a face (the red one in see Sketch 10) might simultaneously belong to several boxes, each of them suggesting a different perspective; thus, that face has an ambiguous spatial collocation. We can easily see the practical effects of such a strategy in Sketch 11, which displays several of the possible simultaneous perspectives contained in a single detail ofSoaring. Interestingly, because of their shared surfaces, the perspective boxes used by Klee form a wide network of connected elements. Notice: not just a linear chain of elements, but a true net, which allows a multiplicity of possible circular courses .

This kind of construction makes me think to something like the hypercube displayed in Sketch 12and this of course recalls the Duchamp’s pet; the fourth dimension. Thus, look at Poster for the Third Chess Championship (1925) (Fig. 35), where Rhonda Shearer showed several analogous spatial inconsistencies.

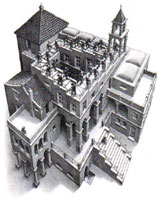

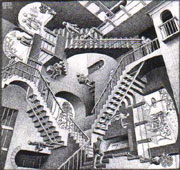

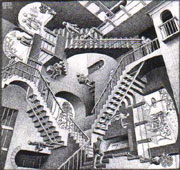

One of the most famous 3D impossible objects of Escher’s is Ascending and Descending (1960) (Fig. 36): on the roof of a building we see an endless staircase. Once again we have a circular course ever returning to its starting point. It is well-known, and Bruno Ernst explained it carefully, that the building, which has the impossible staircase on its roof, has a strange perspective structure, shown in Sketch 13. More than any verbal explanation, animations 3 and 4 help us understand the key reason for this. Animation 3 is a perspective sketch with one only vanishing point. It starts by showing three distinct parallel planes. They are perspectively represented with three closed polygonal lines (namely three rectangles) whose edges are of course not connected with each other. But by slightly rotating one of the edges of the optical pyramid around the vanishing point, we get a spiraling polygon, which joins in a single connected line the edges of several planes. The same holds if perspective has three vanishing points: look at Animation 4, which explains the perspective structure of Escher’s impossible building. Here is the surprise. Look at Sketch 14: the impossible room in Klee’sChess is based just on the construction presented in animation 3, thus it is deeply linked to the impossible building of Escher’s Ascending and descending. (Further explanation for this can be found in the article cited above ).

Thus, in these cases both Klee and Escher conceived perspective in terms of an iterative process, whose outcome is the spiraling, growing motion we saw in their buildings, as well as in a nautilus shell; thus they thought of the vanishing point as a sort of attractor of a dynamic system.

Can we see anything of this in Duchamp’s work? Not exactly the same, but in a way the answer is: yes, there are.

One of the major achievements of Duchamp on perspective is of course the lower half of the Glass (we shall consider the Completed Large Glass, 1965 (Fig. 37)). Thus, look at the Slide, a perfect perspective box which contains the rotatory element named the Water mill. Many other rotatory elements can also be found in the lower part of the Glass, such as the Chocolate grinder or the Oculist chards, but particularly the pathway described by the Sieves or the Toboggan have the feature of a spiral shell we are interested in.

The analogy between these elements and the perspective spirals we saw above is admittedly weak. But look now at Rotary demisphere (1925)(Fig. 38). Animation 5 can help visualize the surprising perspective depth effect one yields once a similar device is rotating. This is quite close to Klee’s and Escher’s idea of considering the perspective vanishing point as a sort of attractor of an iterative process which implies spiral motions.

click to enlarge

Figure 34

Paul Klee, Soaring,

Before the Ascension, 1930

click to enlarge

Sketch 12

Hypercube

Figure 35

Marcel Duchamp, Poster for the

Third French Chess Championship, 1925

click to enlarge

Figure 36

M. C. Escher,

Ascending and Descending,

1960

Sketch 13

Sketch shows the strange perspective

structure of Escher’sAscending and Descending

Sketch 14

The impossible room in

Klee’s Chess

click to enlarge

Animation 3

One vanishing point

perspective, with iterative

spiralling motion

Animation 4

Three vanishing points

perspective, with iterative

spiralling motion click to enlarge

click to enlarge

Figure 37

Marcel Duchamp,

Completed Large Glass, 1965

click to enlarge

Figure 38

Marcel Duchamp,

Rotary Demisphere, 1925

Animation 5

Fac Simile of the spiralling motion

visible as the Rotary Demisphere is rotating

click to enlarge

Figure 39

M.C. Escher, Another

world II, 1947

Figure 40

Paul klee, Perspective

with inhabitant, 1921

What I said so far shows clearly that the theme of the impossible 3D objects and the one of an enlarged conception of the perspective are tightly linked to each other. Thus I want just to recall some of Escher’s experiments on perspective which Klee and Duchamp also did with similar outcomes.

In Escher’s Another world II (1947) (Fig. 39)the only vanishing point (roughly in the center of the print) must be considered at once on the horizon, or at the zenith or at the nadir, depending on which bird (and which wall) we are considering. The same holds for Klee’s Perspective with inhabitants (1921)(Fig. 40).

In Relativity (1953) (Fig. 41) Escher needed three distinct vanishing points to represent a world with three different gravitational fields, where people can walk on the walls as well as on the floor or the ceiling. In Klee’s Arab town (1922) (Fig. 42) we see a similar effect: the ground plane containing the floor of the higher part of the painting is the same plane containing the back walls in the lower part.

The fluid perspective in Escher’s House of stairs (1951) (Fig. 43) could be also explained by Klee’s idea of a stray viewpoint, and the final outcome could be compared with the one ofSoaring.

click to enlarge

Figure 41

M.C. Escher, Relativity, 1953

Figure 42

Paul Klee, Arab

Town, 1922

Figure 43

M.C. Escher, House of

Stairs, 1951

Finally, as far as Duchamp’s perspective experiments are concerned, Shearer showed a quantity of different perspective tricks devised by Duchamp, ranging from stray viewpoints, multiple vanishing points, fluid perspective, photographic overlapping, and so on . Of course, they maintain an high degree of similarity with the ones of Escher and Klee.

Let’s now return to the impossible objects, and see them from another viewpoint.

click to enlarge

Figure 44

M.C. Escher, Waterfall, 1961

Sketch 15

The simple tribar

underling the building

of Waterfall

What do they represent? Especially in Escher’s case it is evident that they are variation on a leitmotiv: the one of perpetuum mobile. Look at Waterfall (1961) (Fig. 44) or even at Ascending and Descending, which explicitly show endless motions. But look even at the simple tribar (Sketch 15) which underlies the building of Waterfall. As we go with the eye along its bars, we perceive a sense of depth, we feel we are leaving the plane where the bars are actually drawn, to enter in the third dimension; and the pathway is really endless because, once the turn is completed, we can repeat it again and again; every time we find ourselves at the starting point.

Thus the impossible objects belong to a world which isn’t subjected to the law of thermodynamics: here entropy doesn’t increase, but reduces itself, to allow perpetual motions, such as inWaterfall.

A similar overturning is exactly what happens in complex systems with self-organization, which is one of the key concept in complexity sciences. Self-organization means that a system, provided certain conditions (one of them being the complexity of the system itself) spontaneously reduces its entropy, by introducing new levels of order among its elements. The slogan coined by Stuart Kauffman , Order for free, effectively captures the essence of the stunning and seemingly paradoxical discover of a self-established order.

Now, if Klee, Duchamp and Escher guessed something about self organization as I believe and as I tried to highlight, then the impossible objects in a way could express with their paradoxical properties the surprising order-for-free nature of complex systems.

After all, something similar has been already said by Jean Clair about the Glass:

Michel Carruoges noticed that the intricate machinery of the Glass shows several analogies with other imaginary machines and engines, devised in same period by Jarry, Roussel, Kafka… Several years after, Jean Clair recalled Carrouges’ statement, and further deepened the parallelism, including in the list a quantity of pseudoscientific inventions which were popular in those years. One of the leitmotivs of those peculiar machines (Glass included) was that they produce more energy than they use, said Clair, thus they are variations on the theme of the perpetuum mobile. In fact they overturn the reality principle (the second law of thermodynamics) into the pleasure principle (the dream of an energy completely free and available).

In short, in my way of seeing things, we can group impossible objects and these machines together.

click to enlarge

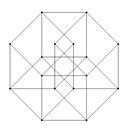

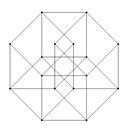

Sketch 16

Necker Cube

But a further connection can also be found, particularly referred to the Necker Cube (Sketch 16), which underlies several impossible objects, such as the Impossible Bed of Apolinaire enameled. Indeed, as Rosen observed, the Necker Cube encompasses within itself, thus we can connect it to the same themes we discussed for the self-encompassing topological figures: hence feedback looping and self-reference.

5. A unifying reading perspective

In conclusion, I would like to delimit the context in which this paper should be read.

Often it happens that many people at once, unconsciously, independently and following different courses, elaborate the same new ideas and concepts, and help cement them into the Zeitgeist. In fact they contribute to the emergence of new sensibilities and new ways of observing, interpreting and understanding the world. This was the case for Klee, Duchamp and Escher: I believe they expressed (being in advance on their time) and contributed towards ideas that would grow and be affirmed. Nowadays, this new paradigm, this new way of seeing things is expressed by the so called complexity sciences.

Reiner Hedrich stressed some salient traits in the development of complexity sciences. Here I’m interested in two of them. First, the gestation period of the new theories has been very long, about one hundred years. This long latency period, necessary to find a solid mathematical theory useful to describe dynamic systems behavior generously covers the lifetimes of Klee, Duchamp and Escher. Thus, in a way, they were immersed in a stream of ideas and concepts which were still under construction and organizing in theories. I’m talking about a nascient stream in the cultural subconscious, not one that was flowing on the surface of the well established scientific culture of those years; thus I don’t think that our artists could have been directly influenced by those scientific ideas; generally speaking, even admitting the possibility of such an exchange of views, in my opinion it is easier to think it happened in the opposite direction. With a few exceptions: for some aspects (I think of concepts such as instabilities and chaos) scholars acknowledge Duchamp has been influenced by the reading of Poincaré; but they are just only some aspects of his complex thought; the same holds for Klee’s possible understanding of (evolutionary) biology and natural sciences, or for the mathematical readings of Escher, which moreover in some cases he admitted to be unable to understand. The second feature in the development of complexity sciences stressed by Hedrich is that the grounding ideas of the new paradigm, the kernel of complexity, didn’t deal with a specific disciplinary field: instead, they are a sort of conceptual foundation, a shared background for any empirical discipline dealing with complex systems. This fact makes it conceivable that there was, to some extent, a widespread and unconscious emergence of such ideas, even though in purely qualitative and intuitive terms. In other words, I’m talking about quite general concepts, and not about specific subjects or details of a well-defined disciplinary field: it makes possible that the same ideas could have been grasped by someone in more intuitive forms, which is what I’m suggesting for Klee, Duchamp and Escher.

The concepts I’m talking about are closely related to each other, they form a tangle of interconnected ideas, that bringing one of them to the light, mostly implies that many (or even all of) the others could also somehow come out. Really, it is impossible to examine thoroughly one of them without revealing a cascade connection with each other. Indeed, the idea of cyclic dynamism of a system entails feedback, recursion and self-reference; in turn self-organization, fractals and chaos are entailed, and again emergence, dynamic and unsequilibria, (co)evolution; further, the visual expression of such a complexity needs new and different ways to conceive the space, where new and more complex relations may occur between its elements; thus, the represented space has strange topological properties.

It is well-known that complexity introduces several relevant changes in the way we used to know the world. This is not the place to discuss them: I’ll limit myself to summarizing some of them.

First: mainly due to both deterministic chaos and sensitive dependence on the initial conditions which characterize the dynamical systems, we have to accept two weaker versions of both the causality principle and determinism.

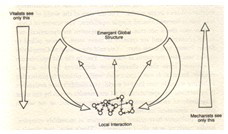

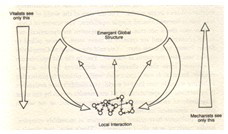

click to enlarge

Sketch 17

Diagram explaining

concept of complexity

Second: because of the concept of emergence, the reductionist approach is not more suito study complex systems. This is sometime expressed by opposing reductionism and holism. I like the way Chris Langton expresses the concept by means of Sketch 17 which I took from Roger Lewin .

To effectively explain the radical change in the way of seeing the world implied by complexity, a set of dichotomies is often used, which confronts old paradigms with new:

simplicity-complexity, reductionism-holism, determinism-uncertainty, quantity-quality, necessity-contingence, predictability-unpredictability, reversibility-irreversibility, repeatability-unrepeatability, causality-randomness, law-chaos… Interestingly, if we attempt to describe Klee, Duchamp and Escher by choosing either of the poles in such dichotomies, we always have to choose the second one.

As far as Duchamp is concerned, the discussion about the crisis of determinism and reductionism has been already widely discussed, particularly in relation to the ideas of Poincaré’s.

Coming to Klee, I want just recall his essay titled Exact experiences in the field of art , where he expressed a concept which is one of the leitmotiv of his activity as both artist and teacher: the freedom and the intuition of the artist act in the space between law and unpredictability, but always remembering the necessity of both:

Oh, don’t let the eternal spark become completely smothered by law’s measure! Take steps in time! But don’t go away from this world completely.

Escher expressed a similar ambivalence with his prints, in the paradoxical coexistence of extreme formal rigor and uncertainty, mathematical exactness and instability, rigorous application of exact principles and unpredictability in the outcomes.

On the other hand, only a few words are needed to recall that Klee, Duchamp and Escher built their work as organisms, composed by a number of interacting elements, where the whole is always greater than the sum of its parts. In their works complex processes are mostly represented, whose outcomes can be emergent, unexpected properties. We can dissect them, but in so doing we always lose something. This is the true essence of their holistic art.

Notes

1. Roberto Giunti, “R. rO. S. E. Sel. A. Vy”, Tout-Fait : The Marcel Duchamp Studies Online Journal 2.4 (January 2002) Articles <https://www.toutfait.com/duchamp.jsp?postid=1240&keyword=>.

2. < http://www.mat.uniroma1.it/venezia2005/>.

3. Roberto Giunti, “Percorsi della complessità in arte: Klee, Duchamp ed Escher”, in: M. Emmer (ed.)Matematica e Cultura 2003 (Milano, Springer Verlag – Italia, in print)

4. Douglas R. Hofstadter, Godel, Escher, Bach: an Eternal Golden Braid (New York, Basic Book, 1979)

5. Teuber M. R. “Perceptual theory and Ambiguity in the Work of M. C. Escher against the background of 20th Century Art”, , in H. S. M. Coxeter, M. Emmer, M. L. Teuber, R. Penrose (ed.) M. C. Escher: Art and Science, (North-Holland, Amsterdam, 1986)

6. Giunti, R. “Una linea ondulata lievemente vibrante. I ritmi della natura nell’opera di Paul Klee”, Materiali di Estetica No. 2, (2000)

7. Giunti R. [6]

8. Whitehead E. P.

“Symmetry in Protein Structure and Functions”, in H. S. M. Coxeter, M. Emmer, M. L. Teuber, R. Penrose (ed.) M. C. Escher: Art and Science (North-Holland, Amsterdam, 1986).

9. Calvin M. “Chemical Evolution”, Oregon State System of Higher Education, Eugene, Oregon, 1961

10. R. Giunti [1], p. 13, <http://www.toutfait.com/duchamp.jsp?postid=1240&keyword=>.

11. Shearer, R.R.

“Marcel Duchamp’s Impossible bed and Other Not Readymade Objects: A possible route of Influence from Art to Science (Part I and II). “ Art & Academe, 10:1 & 2. (Fall 1997 and Fall 1998) <http://www.marcelduchamp.org/ImpossibleBed/PartI/> and <http://www.marcelduchamp.org/ImpossibleBed/PartII/>

12. Escher M. C. The Graphic work (Bendikt Taschen Verlag, Koeln, 1992)

13. Giunti R. “Paul Klee on Computer. Biomathematical models help us understand his work” in M. Emmer (Ed.) The Visual Mind 2, (The MIT Press, Cambridge MASS, in print)

14. Tony Phillips “The topology of Roman Mozaic Mazes” in M. Emmer (Ed.) The Visual Mind (The MIT Press, Cambridge MASS, 1993).

15. D. J. Wright, Dynamical Systems and Fractals Lecture Notes, <http://www.math.okstate.edu/mathdept/dynamics/lecnotes/lecnotes.html>.

16. R. Giunti [1], p. 11, <http://www.toutfait.com/duchamp.jsp?postid=1240&keyword=>.

17. J. Clair, Duchamp at the turn of the Centuries, ToutFait Journal, Issue 3. <http://www.toutfait.com/duchamp.jsp?postid=877&keyword=>.

18. Giunti R. [1], p. 13,<>

19. Shearer R. R. [11]

20. Penrose L.S., Penrose R. “Impossible Objects: a Special Type of Visual Illusion”, Brit. Journal of Psycology, vol. 49, 1958

21. Giunti R. “Analysing Chess. Some deepening on the concept of Chaos by Klee”

<> or <http://members.tripod.com/vismath/pap.htm>

22. Indeed, Klee gradually passed from a first conception, where things are mechanically enchained to each other in a rigid, linear successions, with a well defined cause-effect relation (look at the drawing Parade on the track, 1923) Fig. 45 to a final conception where each thing is connected with each other in a complex network, and causes and effects are not clearly distinguished: look at the pedagogical sketch (sketch 18). Its caption is says: «Building of an higher organism: the assembling of parts viewing at the overall function».

click to enlarge

Figure 45

Paul Klee, Parade on

the track, 1923

Sketch 18

Pedagogical sketch by Klee

The framework of Soaring is just the first important achievement of such a creative course, which will lead in the late works to the theme of morphogenesis.

23. Shearer R.R. “Examining Evidence: Did Duchamp simply use a photograph of “tossed cubes” to create his 1925 Chess Poster?” Tout-Fait Journal, issue 4, <http://www.toutfait.com/duchamp.jsp?postid=1375&keyword=>.

24. B. Ernst, Der Zauberspiegel des M. C. Escher (Taco, Berlin, 1986)

25. Giunti R. [21]

26. Shearer R. R. “Why the hatrack is and/or is not Readymade: with interactive software, animations and videos, for readers to explore”, Tout-Fait Journal, Issue 3, <http://www.toutfait.com/duchamp.jsp?postid=1100&keyword=>

27. Kauffman S. At Home in the Universe. The Search for the Law of Self- Organization and Complexity(Oxford University Press, 1995)

28. Carrouges M. Les Machines célibataires (Arcanes, Paris, 1954)

29. Clair J. Marcel Duchamp ou le grand fictif (Galilée, Paris, 1975)

30. Rosen, S. M. “Wholeness as the Body of Paradox”. 1997 <http://focusing.org/Rosen.html>.

31. Hedrich R. “The Sciences of Complexity: A Kuhnian Revolution in Sciences?” Epistemologia XII.1 (1999) <http://www.tilgher.it/epiarthedrich.html>

32. Lewin R. Complexity. Life at the edge of chaos (The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1999)

33. The essay is contained in: Klee P. Das Bildnerische Denken (Basel: Benno Schwabe & Co., 1956)

34. P. Klee, Tagebücher von Paul Klee 1898-1918 (Köln:Verlag M. Dumont Scauberg, 1957), note 636, 1905

Figs. 1-2

©2003 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris. All rights reserved.