Heidegger’s reimagining of the artwork was instrumental in forcing a re-evaluation of modern aesthetic assumptions in the first half of the twentieth century. Heidegger’s theory of the origin of the work of art derives from a hermeneutic analysis of a single van Gogh masterpiece. On Heidegger’s view, the artwork provides a substantive and practical way of accessing the nature of art even if questions remain about all manifestations of the nature of art in general. This paper turns his analysis to an alternative influential artwork, Duchamp’s Fountain. I argue that Fountain presents difficulties for Heidegger’s method, some of which can be accommodated. However, the requirement to confine phenomenal engagement to the art object alone leads to problems when the object is appropriated from outside the artworld, not exhibited, and only one photograph bears witness to its existence. The prospect of broadening the focus of our attention from the art object alone to the “drama” of Fountain provides for a much richer phenomenal engagement. However, this move runs counter to a second stipulation of Heidegger’s approach – that the artist’s intentions and her performative acts in creating the object should be excluded from our engagement with the work. Duchamp’s radical move with readymades and Fountain, in particular, disarms more than Heidegger’s early post-modern conception of an artwork. It also places pressure on aesthetic theories that lack the capacity to reset ontological boundaries when deeper transformative experiences lie beyond the remit of the object alone, or when art-relevant concepts are appropriated into and out of the realm of art. Duchamp points to a richer means of engaging with artworks than the one construed by Heidegger, one that includes consideration of the relevant artmaking acts.

The making of Fountain

On the eve of the United States entering the Great War, an eccentric band of anarchists purchased a urinal for display as an artwork. Rejected by the curators, the urinal never is exhibited.1 The object itself, Fountain, by R. Mutt (fig. 1) is lost or destroyed shortly after the exhibition ended and there remains nothing for any museum to “preserve.” No artist is needed to authenticate a non-existent art object. There is no “thing” to be “conferred the status of candidate for appreciation” in Dickie’s terms.2 “Nothing to see here” is normally a vain attempt to have the public gaze averted, but what if this whole art appropriation exercise becomes one of the most significant art performances of the twentieth century?3

The Origin of a Work of Art

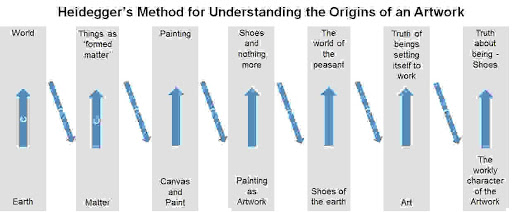

Nearly twenty years later, Martin Heidegger circles a pair of old shoes depicted in an oil painting by Vincent van Gogh (fig. 2). Heidegger4 leads us through a phenomenal engagement with this artwork and in so doing enunciates a theory of the origin of a work of art. Heidegger outlines how both artist and work are the co-dependent result of the art that is their source.5 He applies a metaphor linking the material reality of “earthly things” with the “world” they reveal. His method of interpretation is both multilayered and cyclic with each earth-to-world relation revealing the next.Heidegger develops his earth-to-world notion through the medium of the artwork. He starts from a position that sees the “nature of things” generally as “formed matter”.6 On this account, the formed matter of an artwork, its “thingly” nature, so to speak, comprises material things such as paint and canvas.7 Artworks do a certain kind of work in revealing the truth of how things act in the world – the van Gogh artwork itself displays its workly character in revealing a pair of peasant shoes “and nothing more.” The shoes themselves display their own workly character as equipment of the earth protected in performing their role in the world of a peasant.8 This revelation about how the shoes are “working” in the world of a farm worker brings us back to the workly character of the artwork itself. The artwork’s “work” reveals the “truth of being” for the shoes in the painting. Finally, Heidegger captures this revelation from a particular artwork and proposes, albeit tentatively, how it might be, more generally, for the workly nature of all great works of art. He concludes that art just is truth, but truth construed in a radically different way. It is the “truth of beings setting itself to work.”9 Here “beings” is read as a verb, comprising multiple dynamic actions of things over time. In the case of the van Gogh artwork, the truth of a particular “being” (i.e. the truth of the shoes doing their work), is made to “stand in the light of its being.”10 This process of engagement leads us to see what and how this “thing” (i.e. the shoes) is in the context of its world.

In this way, a work by a great artist “discloses a world” for us, revealing an endless array of possibilities that can flow from a multitude of similar phenomenal engagements with the artwork. Heidegger’s phenomenological hermeneutic analysis of a painting turned modern aesthetic theory on its head and came to be an influential forerunner of postmodern art interpretation.11

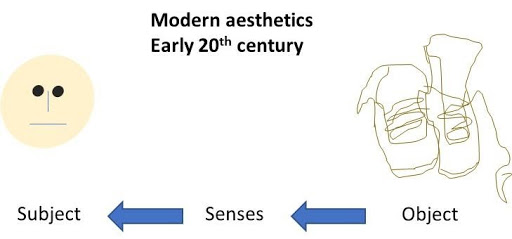

For Heidegger, modern aesthetic theory,12 popular among philosophers in the early twentieth century, views the art experience as “subjects” accessing art “objects,” through the senses (fig. 4). Artworks are the result of creative exercises that reflect the experiences of the artist.

The artist embeds these experiences in the body of the artwork and, in-turn, the artwork elicits similar experiences in the art consumer.13 Heidegger views modern aesthetics problematically in that it creates a subject/object dualism. In short, he sees modern aesthetics as making art available to be “consumed” and, along with technology, science, and culture, is part of a world trend to objectify and control the whole of reality.14 According to Heidegger, this subject-to-object view of aesthetics mischaracterises the way we actually encounter the world on a day-to-day basis. Heidegger does not deny that the subject-object view of the world forms part of the artwork experience, it is just that a richer engagement with art derives from a more fundamental phenomenal connection with things in the world.

What applies is a more complex interweaving of subjective self and objective things in the world. In our use and experience of objects, we are colonised by them directly into a unified engagement with the artwork and its contents. We become immersed in a largely unconscious process of our lived experience of those things.

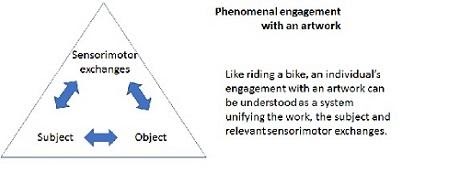

To understand how Heidegger sees this unified system working, it helps to reflect on the lived experience of a bike-rider.

A champion cyclist effects manoeuvres rapidly and unreflectively and only occasionally stops to think if an error has been made or a change of movement is needed. Heidegger believes an everyday notion of direct phenomenological access better reflects our encounters with artworks than the more traditional account of a subject consuming the rewards of an art object (see fig. 5). In clarifying his account of phenomenal engagement, Heidegger warns against seeing it exclusively as a phenomenal experience in which the participant is engaged with the artwork. Were this exclusively the case, the person would be unable to distinguish her being from the thing.

On the other hand, it is incorrect to see the artwork entirely in a distinct subject-to-object relation. He sees it as a kind of experience lying somewhere between or moving between a distinct subject and object stance and a total unification of the self with the artwork.15

Heidegger demonstrates his theory of phenomenal aesthetics by guiding us through a series of encounters with the van Gogh painting and its contents – “a pair of peasant shoes and nothing more.” 16

But then, we are made to see the way the shoes are shaped and presented, and what the shoes are as essential equipment for a wearer, a person who toils on the earth. The shoes are understood, both in themselves and in their relationship to all the other things in the world they suggest. You can see the “truth” of the shoes encountered in the artwork because you have experienced it directly through the art of the painting. Heidegger’s phenomenological method provides a novel combination of lived experience and hermeneutic analysis which describes and interprets the lived experience. Moving back and forth between these two modes of thought, he takes us in ever widening circles encountering individual things as resources of the earth, and how they work and relate to the people who work with them. These parts reveal the whole and the world is seen in the work of art and, in turn, the whole discloses the truth in the parts (e.g. the shoes). Three kinds of “work” are relayed here; the woman using the shoes as equipment as she toils in the field, the work of the artist through the artwork bringing to life the world of the shoes and the woman, and the works done by great artists who, through their art, disclose a seemingly unlimited number of new ways of seeing the true nature of everyday things.

If Fountain was Heidegger’s chosen artwork

Heidegger’s theory of a work of art had one artwork as its guiding source. But what if Heidegger chose Duchamp’s Fountain rather than van Gogh’s Shoes as his starting point? A theory of the origin of an artwork should be robust enough to cover a work that perhaps more than any other provided the grounds for changing what we understand art to be. Could Fountain launch Heidegger’s theory?

This paper will review Heidegger’s theory employing Duchamp’s Fountain as the subject artwork. It will proceed by first clarifying why focusing on Heidegger’s theory and Duchamp’s Fountain is important. It will then attempt to answer four questions that this encounter raises. It will show that the theory is found wanting in some key respects. Finally, it will conclude that the identified limitations of Heidegger’s theory apply to other approaches which share Heidegger’s commitment to a fixed ontology for artworks and the exclusion of performative acts in the making of an artwork.

Why Heidegger’s theory?

Heidegger’s theory was a seminal influence in early post-modern art criticism. It helps explain artwork contributions that extend beyond the Kantian notion of “disinterested pleasure,”17 thereby opening up the possibility that great art will reveal new knowledge, and novel ways of seeing. This, in turn, shows how the creation of artworks can contribute in a profound way to how individuals and communities see themselves and provide a major impetus for the evolution of culture. Heidegger’s “Origin of the Work of Art” became an important base for other philosophers including existentialists Jean Paul Sartre and Maurice Merleau-Ponty and later post-modern theorists such as Hans Georg Gadamer, Paul Ricoeur, Jacques Derrida, and Emmanuel Levinas, all of whom repurposed Heidegger’s approach into their own interpretations of aesthetics.18

Many current theorists share with Heidegger an understanding that the revelatory or affective art experience derives from an engagement with the artwork and the artwork alone. Extrinsic features including artistic intention, social relations to the artwork, and art interpretation, may be excluded as not constitutive of the artwork itself. Some highly influential theories also share with Heidegger a respect for standard ontological boundaries regarding the chosen communication medium – whether it be painting, novel writing, drama, or poetry, these media are viewed as determinately distinct forms. Perhaps, most tellingly, the prospect that an object, concept, or material may be transferred in to or out of the artworld entirely by the design or intention of its maker, collaborator, or appropriator necessitates a fluidity in ontological boundaries that is beyond the countenance of Heidegger and like theorists. These two features, intrinsic features confined to the artwork and media boundaries around artmaking, prove crucial to this analysis. Proceeding to test Fountain against Heidegger’s theory arguably has implications for a broader group of contemporary art theories.19

Why Fountain?

Repurposing “found” or manufactured objects as artworks was an early twentieth century innovation that created a paradigm shift in philosophy of aesthetics. Fountain and similar “readymades” are credited with influencing the development of many later innovations including pop art, op art, conceptual art, minimalism, performance art, and art-reflexive or self-referencing artworks.20 Fountain is unique among repurposed objects because Fountain has doubtful provenance and was lost or destroyed soon after being rejected for exhibition. A background such as this provides a uniquely poor platform for an art object by itself to provide rich aesthetic or revelatory value. There are numerous critical assessments of why Fountain played a significant role in twentieth century art.Most of these accounts fall broadly into two camps. Firstly, there is a focus on the object as anti-art, a disruptor mocking the hallowed institutions of art including the veneration of great artworks, the artist as genius, and the status of art professionals as supreme arbiters of taste.21Fountain is simply “chosen” for admiration in the artworld when it is otherwise indistinguishable from hundreds of identical objects, mass-produced for their instrumental bathroom value. The very idea that a work with such a tenuous claim to artworld status should be presented as such establishes “mockery” as part of the artist toolkit. On this view, Fountain is a seminal source for many later art disruptors.

Second, Fountain references the concepts, planning and collaborative actions that brought into view Fountain’s transformative nature. The simple act of choosing an object, together with the subsequent associated collective actions that made it art, expanded our concepts of what art can be. Art becomes fundamentally conceptual and not merely “retinal” like so much art that went before it. Van Weeden claims that in choosing Fountain as a work of art, Duchamp recasts the space that art occupied – everything could be art.22 Artworks and artmaking are no longer distinct. They occupy a continuum of relations wherein artmaking acts are seen as the principal output and artworks themselves can be a window revealing these acts. Artwork and art acts are juxtaposed on a level playing field. Moreover, Fountain affirms that artmaking can be as straight-forwardly simple as selecting an object or concept as art. This makes the artworld the province of whoever deems what they do as “art”; no hierarchies involved; we all get to interpret and judge what is good and bad art.

Artists have available to them an unlimited range of ideas, materials, and audiences to choose from in the making of their art.23 In Roberts view the cognitive, cultural and political tenor of twentieth and twenty first century art is reshaped by Fountain so that we are now all “post-Duchampians.”24

A promising prospect

The idea of applying Heidegger to Fountain has some promise of bearing fruit. Duchamp and Heidegger had much in common in their construal of art. First, they both reject the notion that an artwork harbours aesthetic features gifted to the viewer through the senses. Heidegger rejects modern aesthetic theory on these grounds and Duchamp rejects “retinal” or visually-appealing art,opting instead for art that engages the mind. Second, both see engaging with an artwork as opening a multiplicity of revelations and interpretations. For Heidegger engaging is an in-the-moment experience for the individual with the work, a “presencing” that does not exhaust the world of meanings.25 This enables each individual engagement (for different people and different times) to produce a multiplicity of phenomenally grounded revelations.26 And for Duchamp, “aesthetic relativity” situates artworks as nodes in a relational web comprising multiple meanings.27

So with this promising beginning the paper will review key features of Heidegger’s model through the prism of Fountain.

Applying Heidegger’s theory of art to Duchamp’s Fountain

While Heidegger described a phenomenal engagement with one particular artwork, he intends his theory to apply to how we might engage with other great works of art. Engaging in this way with a work of art involves at least four relevant criteria implied or explicitly entailed by Heidegger’s model. These can be expressed as a list of questions needing answers:

1. What kind of thing is the “artwork” or object under study?

First, we need to settle on the work’s ontology or decide on exactly what kind of thing the artwork is. This first step seems a trivial one for conventional art; the artwork just is the painting, or sculpture, etc., before you. However, Fountain is anything but conventional. Is it art, plumbing, or something else?

2. Is there a singular creative agent behind the making of the work?

This second key feature follows from Heidegger’s assumption that each great work of art requires a singular great creator to realize and illuminate profound and unique truths about things in the world through their art.

3. What counts as “earth” in the creation of Fountain?

This third question involves fundamental resources (“the earth”) being “worked” to create and inform how things are in the world?

4. Does Fountain stand as an artwork, in its own right, without relying on the artist’s intentions or performative acts in its appreciation?

Finally, to be consistent with Heidegger’s model, whatever experiences or revelations arise will stem from a direct engagement with the artwork unsullied by anything external to the work.

Does Heidegger’s model for the creation of an artwork work for Fountain? If so, our phenomenal encounter will need to answer these questions.

What is the nature of Fountain?

Urinal as art object

If art is the origin of the artwork and of the artist, but no art object remains for our gaze, then we will need to rely on a photograph of the original by Alfred Stieglitz.28 Resting on a plinth, the object is transformed just enough so that its abstract form can be appreciated. It soon becomes clear that the thing depicted is a male urinal.

It is called Fountain and it is signed “R Mutt.” Before it was transformed for exhibition, the urinal was designed and produced to be restroom equipment and not a work of art. Whoever was the original designer is not the “artist” here. The urinal itself is transformed in the most meagre of ways – turned on its side with the inlet facing the viewer so it suggests a fountain. It is named, signed, submitted for exhibition, and rejected. There is not enough artistry here to call the “transformer” an artist either. No artwork and no artist should mean, at least in Heidegger’s terms, that this is not art. But whatever happened in the New York Spring of 1917 changed twentieth century art. Finding the “art” in this puzzle necessitates a different path to the one taken by Heidegger with van Gogh’s Shoes.

Fountain as drama

No object remains and the collaborators are long since dead so the story of the Fountain is sketchy and uncertain. However, what is known is that it has a beginning, a middle, an end, and a very long epilogue. It also has “dramatis personae,” an “auteur” of sorts. There is no art object, but there is a mildly vulgar prop around which the drama unfolds. The story has atmosphere, a backstory, it is riddled with puns.

There is not the space for a full exegesis of Fountain as drama or as a succession of performative acts. Doing so would reveal a cast of larger-than-life characters, a famous photographer, a most interesting director and the no-rules-barring-entry exhibition curators who broke their only rule by excluding Fountain from being exhibited.29

The drama would explain the quixotic quest of Dada to get a mad world to abandon the brutal logic of war on the eve of young Americans signing up for service to the background lyrics of “Johnny get your gun”.30

It would show that Duchamp’s play most probably has not ended. The long epilogue may show that, as he promised,31 Fountain really is for future generations.32

It would appear the urinal, taken as artwork in and of itself, leads to a lean reading; a dead-end. But znderstanding Fountain as a collaborative drama does have the potential to “disclose a world” in the way Heidegger would recognise. Duchamp himself adopted a deliberatively performative stance with regard to his artmaking and its reception by the public:

“You’re on stage,” he explains, “you show off your goods”; right then you become an actor; one accepts everything, while laughing just the same. You don’t have to give in too much. You accept to please other people, more than yourself. It’s a sort of politeness.33

Moreover, Fountain is invested with that polysemic potential that Heidegger sees as a necessary ingredient of great art.34 Is it a pun for “taking a piss” or a crypto-feminist plot for “taking the piss” out of men? Is it art, not art, neither or both; a real case of a true contradiction?35 Even the Fountain-as-drama reading bifurcates into a man-story with artist Joseph Stella, Walter Arensberg art critic, and Duchamp planning the “Fountain play” prior to Duchamp’s execution36 and a less told under-story with Baroness von Freytag-Loringhoven, Louise Norton, Katherine Dreier, and Beatrice Wood playing leading roles37 with Duchamp as ally.. Rival narratives only add to the dramatic potential. If we do accept Fountain as drama for a Heideggerian analysis, this move is still problematic for his theory on a number of fronts. This leads us to the next important question.

Is there a single creative agent behind the making of the work?

While not ruling out collective acts, Heidegger’s project suggests he had in mind that a great artwork was the product of a single great creator uniquely realising her vision through the act of artwork creation. But with Fountain, there is no singular artist to take the mantle of greatness that Heidegger seems to assume is required for artworks to be imbued with the necessary transformative qualities. In Fountain, it would appear a collective of creative talents worked collaboratively, arguably, under the direction of Marcel Duchamp although there remain doubts concerning who exactly played what role in the Fountain drama.38 Removing the stricture of artist as sole creative agent does not affect the overall project dramatically. It means we accept that collective creativity can sometimes be transformative as well. Heidegger at least acknowledged that the “createdness” of the work was to be seen as distinct from the greatness of the singular artist:

The emergence of createdness from the work does not mean that the work is to give the impression of having been made by a great artist.39 In moving forward then, we tentatively have Fountain being read as drama with a collective of creative players. But how might we construe Heidegger’s earth-to-world relation which proves so crucial in his origin of an artwork?

What counts as “earth” in the creation of Fountain

Construing Fountain as drama and assuming a collective process of creation does not fully address the problem of applying Heidegger’s model to this iconic creation. A third hurdle for Fountain as drama relates to the earth-to-world metaphor. Heidegger enlists a variety of “world-forming” material resources that normally count as “earth.” While the urinal is certainly “material,” we have shown that it is an inadequate source for what Fountain becomes. In the case of van Gogh’s Shoes, the connections Heidegger makes between earth and world via the constitutive materials of the artwork and the relations of the shoes to the peasant’s work40 provide a rich account of how a great artwork can be culturally transformative. Contrasted with this rich account for ‘Shoes’, the physical object of the urinal by itself tells us little about how ‘Fountain’ comes to be a major catalyst in changing twentieth century art. In the case of Fountain then, what counts as earth? What can be the constitutive source for the “thingness” of no-thing? The construal for earth needs to be extended to, somehow, accompany the ‘Fountain’ performance. This includes the formative ideas that lead to the playing out of “Fountain as drama”; or, at least, the available records of what is said and done to enact those ideas as the basis of a plan to acquire a ready-made, display it, reject it, etc. Heidegger provides us with a clue in his discussion of poets using words inhe way artists use pigment:

To be sure, the poet also uses the word — not, however, like ordinary speakers and writers who have to use them up, but rather in such a way that the word only now becomes and remains truly a word.41

In fact, Heidegger says that the defining feature of all great works of art is found in “poesis” or their poetic nature of bringing important things into being:

All art, we learn from “The Origin of the Work of Art,” is essentially poetry, because it is the letting happen of the advent of the truth of what is. And poetry, as linguistic, has a privileged position in the domain of the arts, because language, understood rightly, is the original way in which beings are brought into the open clearing of truth, in which world and earth, mortals and gods are bidden to come to their appointed places of meeting.42

The constitutive origins of words are phonemes, and phonemes as physical acoustic artefacts may qualify as the “earth” of poetry. But what about the succession of performative acts at the heart of the “Fountain drama”? The earth could be seen here also as residing in the non-verbal signs and symbols of the actions of the players coupled with these same “acoustic artefacts” informing what is said. With this account of earth, the emerging “artwork” can be seen as the drama derived from performances of the players transforming acoustic artefacts with their utterances and the signs and symbols manifest in their actions revealing a world; a Fountain world.This brings us to the final question.43

Does Fountain stand as an artwork without relying on the artist’s intentions or performative

acts in its appreciation?

So far, we have seen that with some significant adjustments Heidegger’s phenomenal aesthetics can be made to work for Fountain. But a final hurdle remains for his construal. Heidegger is strongly of the opinion that the artwork and the artwork alone should be the focus of our phenomenal engagement:

Where does a work belong? The work belongs, as work, uniquely within the realm that is opened up by itself. For the work-being of the work is present in, and only in, such opening up.44

Moreover, Heidegger emphasises that this engagement should be considered as it is and not be narrowed by its creator:

The thrust that the work as this work is, and the uninterruptedness of this plain thrust, constitute the steadfastness of the work’s self-subsistence. Precisely where the artist and the process and the circumstances of the genesis of the work remain unknown, this thrust, this “that it is” of createdness, emerges into view most purely from the work.45

For Heidegger, direct phenomenal engagement with the artwork requires the undivided attention of the person. Taking into account the artist’s opinions and constitutive actions count as distractions to this primary purpose.

How does Fountain challenge this position? As we have seen, if Fountain is to be read in a manner that exposes us to its full revelatory potential, then it must be interpreted beyond the physical object itself. Reframing Fountain as drama provides such a rich reading. A consequence of this move is that the contents of the artwork necessarily comprise narratives of what the actors do and say. In this regard, it is difficult, if not impossible, to separate the art; that is, the performative acts themselves from the opinions of the actors/artists.

As an example, Louise Norton writes an article in the Blind Man magazine shortly after Fountain’s rejection.46 Her article is both artist opinion and also a key step in a later chapter of the Fountain drama; making it a necessary part of the artwork-drama itself. Problematically for Heidegger’s theory, the performative acts of the artists must be included because they are constitutive of the artwork as drama and contradictorily not included to meet Heidegger’s stipulation of excluding the artist’s opinion. Separating this kind of opinion destroys or obscures the very work itself.

The problem of excluding the artist’s “opinion” and other key constitutive elements from the analysis extends to artworks generally. Access to Shoes suffers from being confined to a hermeneutical analysis of the painting itself. What if a work identical to the van Gogh masterpiece were produced by a forger simply copying the original stroke by stroke? Would we be in error if a phenomenal engagement with the copy means we imbued the shoes with the “earth and toil of the peasant”? Our only means of knowing the copy’s status derives from evidence of the faker’s performative acts in making the forgery – evidence, possibly, only available externally to the painting.

But surely the problem of conflating interpretative opinion with the composition can be addressed by finding a way of distinguishing acts that are part the creators’ critique of their art from those that are part of the art act performance simpliciter? In other words, why not place a boundary around artmaking performative acts and separate these from interpretations that lie outside the artmaking acts? The problem is that “Fountain-play” is not a formally framed orthodox “play” like a Shakespeare play with clear boundaries between the play and the play’s creation. Constitutive acts of the players are no less important than the object created. Duchamp would see other boundaries being blurred as well; the “spectator’s role” after the objects’ creation becomes equally informative of what the work is.47 Fountain has no such clear boundaries. All the creative acts connected to the Fountain drama are both acts of creation and performance with no clear limits of time, space or characters.

Opting for a “Neo-Heideggerian” solution

We have shown Heidegger’s theory provides an inadequate response to Fountain unless four important questions integral to his approach, can be addressed. So why not just “bite the bullet” and accept some adjustments to Heidegger’s theory to enable Fountain to be accommodated? This move has the advantage of preserving the core innovative feature of the theory – hermeneutical phenomenology. Heidegger’s artwork methodology helps explain the revelatory potential of engaging with an artwork while avoiding the subject/object dualism that Heidegger roundly criticises. While adopting a substantially modified “Neo-Heideggerian” theory of the origin of an artwork is plausible, the move creates something like the problem of the old kitchen broom – the one that has three replacement handles and four new heads. It really isn’t the same broom. In addition, the revised theory is lacking an adequate explanatory account for any of the relaxed criteria – for example, how should we understand performative acts of multiple players undertaken over different times and places as the “work” of art when Heidegger’s account is confined to engaging with a single art object ostensibly at one sitting. Even in its expanded “Neo-Heideggerian” form, Heidegger’s original analysis lacks the epistemic resources to accommodate this move and it is therefore lacking in the required explanatory narrative to enable a robust account of Fountain.

Conclusion

Heidegger’s phenomenal hermeneutics was instrumental in forcing a re-evaluation of modern aesthetic assumptions in the early twentieth century. Heidegger’s theory of the origin of the artwork is born from a hermeneutic analysis of a single van Gogh masterpiece. This essay turned his analysis to another great artwork – perhaps the most influential work of the twentieth century – Fountain. While Heidegger’s method can accommodate some hurdles thrown up by Fountain, the requirement to confine phenomenal engagement to the art object alone leads to problems when the object has such limited potential as an influential work of art. The prospect of broadening the focus of our attention to the drama of Fountain provides for a much richer phenomenal engagement.

However, this move runs counter to a second stipulation that the artist’s intentions/opinion and performative acts in making the art should be excluded from our engagement with the work. Adjusting Heidegger’s theory to better accommodate works like Fountain also fails.

This paper focused on the capacity of a single early post-modern theory of art to explain a singular work. However, the two key limitations that defeat Heidegger’s theory also limit similar theories, particularly those approaches that privilege the intrinsic features of the artwork but exclude the actions of artmakers, collaborators and appropriators. It also places pressure on aesthetic theories that lack the fluidity to reset ontological boundaries when the richer revelatory experience is found beyond the exclusive remit of the object alone.

This theory limitation would be of minor consequence if it applied to a singular exception – Fountain. But as we have seen, Fountain is only the first in a long succession of art making practices characterised by repurposing or appropriating objects, concepts, and styles into the world of art from elsewhere. Heidegger’s “Origin of the Work of Art” and like theories are restricted in their capacity to reveal the rich potential of Fountain’s innovative progeny, the very progeny that have helped to define current art practice.

Figures

Figure 1: Fountain – Marcel Duchamp

1917 Photo – Alfred Stieglitz Retrieved from http://academics.smcvt.edu/gblasdel/slides%20ar333/webpages/m.%20duchamp,%20fountain.htm

Figure 2: Shoes Vincent van Gogh, 1886

Oil on canvas, 38.1 cm x 45.3 cm van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Figure 3: Heidegger’s Hermeneutic cycle applied to van Gogh’s painting. Heidegger employs a series of connected earth-to-world relations to understand the origin of an artwork. ‘Things’ like shoes and artworks are ‘formed matter’. Van Gogh’s painting reveals shoes and, in turn, their ‘being’ brings into being the working life of the woman. This very process illuminates the workly character of a particular artwork and, tentatively, for Heidegger, the true nature of all great works of art.

Figure 4: The modern aesthetic model of art requires a subject/object dichotomy between the subject and artwork.

Figure 5: Heidegger’s alternative model for engaging with an artwork

Notes:

1 Robert Kilroy, Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain: One Hundred Years Later, 2017 ed. (Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates: Palgrave Pivot, 2017), 51.

2 George Dickie, “Defining Art,” American Philosophical Quarterly 6, no. 3 (1969): 254.

3 Kilroy, 1.

4 Martin Heidegger, Poetry, Language, Thought, Translations and Introduction by Albert Hofstadter, Perennial Library (New York ; Sydney : Harper & Row, 1975, c1971., 1975), 15-86.

5 Ibid., 17.

6 Ibid., 26.

7 Ibid., 19.

8 Ibid., 33.

9 Ibid., 35.

10 Ibid., 35.

11 Iain Thomson,Heidegger, Art, and Postmodernity (Cambridge University Press, 2011), 65-77.

12 The modern aesthetic tradition that Heidegger criticises had its origins in the eighteenth century through the writing of a number thinkers, the Earl of Shaftesbury and Immanuel Kant, prominent among them. Modern aesthetic theory held that beauty existed in things independent of humans. In the ‘Critique of Judgement’, Kant emphasised that judging the ‘taste’ of an object requires the subject to adopt a state of disinterest to enable the experience of delight derived from the object to be fully appreciated.

Jerome Stolnitz, “On the Significance of Lord Shaftesbury in Modern Aesthetic Theory,”The Philosophical Quarterly (1950-), no. 43 (1961). https://doi.org/10.2307/2960120; Immanuel Kant,

Critique of Judgement (Oxford University Press, 2005), 37.

13 Thomson, 47-51.

14 Martin Heidegger and William Vernon Lovitt, The Question Concerning Technology and Other Essays, Harper Torchbooks: Tb 1969 (New York [etc.] : Harper and Row, 1977., 1977), 116; Thomson, 45.

15 Heidegger, 25.

16 Ibid., 33.

17 Kant, 41.

18 Jacques Derrida, The Truth in Painting (University of Chicago Press, 1987); Hans Georg Gadamer and Robert Bernasconi,The Relevance of the Beautiful and Other Essays

(Cambridge University Press, 1986); Leonard Lawlor and Ted Toadvine, The Merleau-Ponty Reader (Northwestern University Press, 2007), 69-84, 241-82, 351-78; Emmanuel Lévinas and Seán Hand,

The Levinas Reader (B. Blackwell, 1989), 129-65; Paul Ricoeur, “Aesthetic Experience,” Philosophy and Social Criticism 24, no. 2-3 (04/01/ 1998); Jean-Paul Sartre,

Essays in Aesthetics, Essay Index Reprint Series (Books for Libraries Press, 1970).

19 Arguably, Ricoeur, Merleau-Ponty and Gadamer are theorists who fall short in these respects. Paul Ricoeur emphasizes the

singular character of the ‘work’ as crucial in engaging with art. He alludes to the significance of the frame of a painting in

separating the work from its background. In so doing, it provides us with a window on the world of the painting. He finds contemporary

notions of appropriation, for example ‘a chair being placed on a platform’, troubling for art. Ibid.Ricoeur, 30. Merleau-Ponty argues

the authenticity of a painting can only be judged by examining the painting and ‘if the counterfeiter succeeded in recapturing not only the

processes but the very style of the great Vermeers he would no longer be a counterfeiter’. See Lawlor and Toadvine, 261-62. Gadamer comes

closer to realizing the fluidity in art boundaries with his idea of the ‘play’ in artworks and how spectators are not excluded from joining in

the ‘play’ suggested in the work. See Gadamer and Bernasconi, 24. On the other hand, Gadamer understands works of art as being ‘set free’ and

‘released from the process of production because it is, by definition, destined for use’ Ibid., 12. Duchamp’s ‘Bottle-rack’ is viewed through

the object’s determinate character in suggesting the effect it once produced Ibid., 25. The performative acts of the appropriator are not

needed here to fulfil Gadamer’s account of the ‘Bottle-rack’.

20 William A. Camfield and Marcel Duchamp, Marcel Duchamp, Fountain (Houston Fine Art Press, 1989), 88; Calvin Tomkins, Duchamp : A Biography

, 1st ed. ed. (H. Holt, 1996), 455-56.

21 Allan Antliff, “The Making and Mauling of Marcel Duchamp’s Ready-Made,” Canadian Art 23, no. 1 (Spring2006 2006): 57; Camfield and Duchamp, 42; Kilroy, 48.

22 Dirk van Weelden, “Black Coffee. Marcel Duchamp’s Pataphysical Sensism,” Relief: Revue Électronique de Littérature Francaise, Vol 10, Iss 1, Pp 70-76 (2016),

no. 1 (2016): 71. https://doi.org/10.18352/relief.925.

23 If ‘Fountain’ does lead us to a greatly expanded construal of art, it also increases uncertainty concerning the boundaries of art. Where should I draw the line

between what is and is not art? Of course, contesting the boundaries of art did not begin with Duchamp. Resolving the art status of borderline works may be a less

rewarding exercise than finding the pathway that reveals the revelatory potential of any given work despite its status as art or something else.

24 John Roberts, “Temporality, Critique, and the Vessel Tradition: Bernard Leach and Marcel Duchamp,” Temporality, Critique, and the Vessel Tradition: Bernard Leach and Marcel Duchamp,”

6, no. 3 (2013): 256. https://doi.org/10.2752/174967813X13806265666618.

25 Iain Thomson, “Heidegger’s Aesthetics,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2010).

26 Heidegger, 81.

27 van Weelden, 71.

28 Mystery surrounds even this one photograph with some claiming it is not all it seems. See Rhonda R. Shearer, “Why the Hatrack Is and/or Is Not Readymade :

With Interactive Software, Animations, and Videos for Readers to Explore,” Tout-fait 1, no. 3 (2000).

29 Paul Franklin, B., “Object Choice: Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain and the Art of Queer Art History,” Oxford Art Journal 23, no. 1 (2000).

30 Lyrics from the popular song ‘Over There’ by George M Cohen.

31 Camfield and Duchamp, 142.

32 Duchamp in a talk titled ‘The Creative Act’ acknowledges the role of the spectator as collaborator in art-making: “All in all, the creative act is not performed by the artist alone;

the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world by deciphering and ‘ interpreting its inner qualifications and thus adds his contribution to the creative act.”

33Kilroy, 84.

34 Thomson, Heidegger, Art, and Postmodernity, 69.

35 Damon Young and Graham Priest, “It Is and It Isn’t,” Aeon 2018 (2017).

36 The story of ‘Fountain’ is a collection of narratives arising from actions by members and associates of the Society of Independent Artists.

Alfred Steiglitz is credited with the one known photograph of ’Fountain’ taken shortly after its rejection from the exhibition, and Walter Arensberg,

art critic and collector, who together with Joseph Stella and Marcel Duchamp arguably planned the exhibition of ‘Fountain’. Marcel Duchamp himself may

have ‘directed’ much of the execution of the ‘Fountain play’ Camfield and Duchamp, 20-43.

37 There is a significant body of evidence that the women collaborators played a far greater role in Fountain’s creation than has been historically

acknowledged. Beatrice Wood, the ‘Mama of Dada’ along with Henri-Pierre Roche and Duchamp edited the Blind Man which provided narrative for the ’

Fountain’ story. Louise Norton’s article in the Blindman “Buddha of the Bathroom,” The Blind Man1917. played a seminal role in making what ’Fountain’

eventually became particularly given the object’s early disappearance and continuing uncertainty surrounding its origins. Katherine Dreier was the

first to offer the ‘originality objection’ against ‘Fountain’ but subsequently became an advocate for the Society of Independent Artists to rescind

their rejection of the work, Camfield and Duchamp, 28-32. Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven is credited, by some, as being the real creator of

Fountain. See, for example, Irene Gammel, Baroness Elsa : Gender, Dada and Everyday Modernity : A Cultural Biography (Cambridge, Mass. ; London : MIT,

c2002., 2002); Julian Spalding and Glyn Thompson, “Did Marcel Duchamp Steal Elsa’s Urinal?,” Art Newspaper 24, no. 262 (2014). Gammel. Spalding and

Thompson. However others have disputed this claim. See Thierry de Duve, “The Story of Fountain: Hard Facts and Soft Speculation,” Nordic Journal of

Aesthetics 28, no. 57/58 (01// 2019): 42.

38 Anne Sejten, “Art Fighting Its Way Back to Aesthetics: Revisiting Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain,” Journal of Art Historiography 15, no. 2 (2016): 3-4.

39 Heidegger, 63.

40 Ibid., 30-36.

41 Ibid., 46.

42 Ibid., 73.

43 Including the words and actions of all those with a part to play in the making of ‘Fountain’ as drama does not exclude the role of the object i.e.

the urinal itself. It remains a central defining point of reference – one that the ‘Fountain’ players continually reference as

the drama unfolds. In a certain sense, the urinal becomes a ‘prop’ essential to the drama.

44 Heidegger, 40.

45Ibid., 63.

46Norton, 5-6.

47Camfield and Duchamp, 142.

Bibliography

Antliff, Allan. “The Making and Mauling of Marcel Duchamp’s Ready-Made.” Canadian Art 23, no. 1 (Spring2006 2006): 56-60.

Camfield, William A., and Marcel Duchamp. Marcel Duchamp, Fountain. Houston Fine Art Press, 1989.

de Duve, Thierry. “The Story of Fountain: Hard Facts and Soft Speculation.” Nordic Journal of Aesthetics 28, no. 57/58 (01// 2019): 10.

Derrida, Jacques. The Truth in Painting. University of Chicago Press, 1987.

Dickie, George. “Defining Art.” American Philosophical Quarterly 6, no. 3 (1969): 253-56.

Franklin, Paul, B. “Object Choice: Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain and the Art of Queer Art History.” Oxford Art Journal 23, no. 1 (2000): 25.

Gadamer, Hans Georg, and Robert Bernasconi. The Relevance of the Beautiful and Other Essays. Cambridge University Press, 1986.

Gammel, Irene. Baroness Elsa : Gender, Dada and Everyday Modernity : A Cultural Biography. Cambridge, Mass. ; London : MIT, c2002., 2002.

Heidegger, Martin. Poetry, Language, Thought, Translations and Introduction by Albert Hofstadter. Perennial Library. New York ; Sydney : Harper & Row, 1975, c1971., 1975.

Heidegger, Martin, and William Vernon Lovitt. The Question Concerning Technology and Other Essays. Harper Torchbooks: Tb 1969. New York [etc.] : Harper and Row, 1977., 1977.

Kant, Immanuel. Critique of Judgement. Oxford University Press, 2005.

Kilroy, Robert. Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain: One Hundred Years Later. 2017 ed. Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates: Palgrave Pivot, 2017.

Lawlor, Leonard, and Ted Toadvine. The Merleau-Ponty Reader. Northwestern University Press, 2007.

Lévinas, Emmanuel, and Seán Hand. The Levinas Reader. B. Blackwell, 1989.

Norton, Louise. “Buddha of the Bathroom.” The Blind Man, 1917, 2.

Ricoeur, Paul. “Aesthetic Experience.” Philosophy and Social Criticism 24, no. 2-3 (04/01/ 1998): 25-39.

Roberts, John. “Temporality, Critique, and the Vessel Tradition: Bernard Leach and Marcel Duchamp.” Journal of Modern Craft 6, no. 3 (2013): 255-66. https://doi.org/10.2752/174967813X13806265666618.

Sartre, Jean-Paul. Essays in Aesthetics. Essay Index Reprint Series. Books for Libraries Press, 1970.

Sejten, Anne. “Art Fighting Its Way Back to Aesthetics: Revisiting Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain.” Journal of Art Historiography 15, no. 2 (2016): 15.

Shearer, Rhonda R. “Why the Hatrack Is and/or Is Not Readymade : With Interactive Software, Animations, and Videos for Readers to Explore.” Tout-fait 1, no. 3 (2000): 10.

Spalding, Julian, and Glyn Thompson. “Did Marcel Duchamp Steal Elsa’s Urinal?”. Art Newspaper 24, no. 262 (2014): 59-59.

Stolnitz, Jerome. “On the Significance of Lord Shaftesbury in Modern Aesthetic Theory.” The Philosophical Quarterly (1950-), no. 43 (1961): 97. https://doi.org/10.2307/2960120.

Thomson, Iain. “Heidegger’s Aesthetics.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2010): n/a.

———. Heidegger, Art, and Postmodernity. Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Tomkins, Calvin. Duchamp : A Biography. 1st ed. ed.: H. Holt, 1996.

van Weelden, Dirk. “Black Coffee. Marcel Duchamp’s Pataphysical Sensism.” Relief: Revue Électronique de Littérature Francaise, Vol 10, Iss 1, Pp 70-76 (2016), no. 1 (2016): 70. https://doi.org/10.18352/relief.925.

Young, Damon, and Graham Priest. “It Is and It Isn’t.” Aeon 2018 (2017).

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank the Australasian Association of Philosophy Conference and the University of Melbourne Philosophy Post-Graduate Colloquia participants for helpful suggestions on early drafts of this paper.