|

I. Introduction: The Depth of Trifles and the Status of Puns

The Duchampian pun that covered each piece of candy at the opening of Bill Copley’s 1953 Parisian show might, in its richness and ambiguity of meaning, suggest Churchill’s famous description of Soviet

Russia as “a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.” Duchamp designed the square tinfoil wrappers, and inscribed each little gift to the invitees with a simple and original phrase that may well be regarded as his deepest and richest play on words: A Guest + A Host = A Ghost.

At face value, adding only the most obvious and minimal interpretation, the pun seems gentle and harmless enough at a few evident levels that might catch anyone’s interest and mild appreciation:

1. The single resultant (ghost) arises as an amalgamation of the two inputs – the initial consonants of each word in sequence (g of guest followed by h of host), the final two consonants shared by both words (st), and the vowel of one (the retained o of host) used instead of the vowels of the other (the eliminated ue of guest).

2. At a first level of meaning (definitional) behind the amalgamation of letters, the joining of these paired and opposite words (the host who provides hospitality and the guest who receives it) leads to their annihilation (ghost). This curiosity merits at least a smile, and must have intrigued Duchamp.

|

Click to enlarge

|

|

|

|

Marcel Duchamp,

A Guest + A Host = A Ghost, 1953

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

|

3. At a second level of meaning (contextual), the phrase seems even more humorous when inscribed on a candy wrapper – for after one eats the candy, the wrapper remains as a shroud or ghost, the former and now empty covering of an annihilated substance.

4. At a third level (functional), the people were guests at a host’s exhibition – and they left with a ghost generated by the gift of a host followed by receipt and intended usage of a guest.

These levels of meaning might be deemed sufficient to warrant notice and minimal commentary, but scarcely complex or interesting enough to inspire any scholarly exegesis or artistic appreciation. I would like to argue, on the contrary, that Duchamp’s extensive and pervasive wordplays in general (appearing throughout his career, in all formats from offhand remarks, to the titles of most of his works, to explicit publications spanning a full spectrum from single items to extensive lists, and also to large chunks of his posthumous notes) – and the 1953 ghost pun in particular (as perhaps the most complex and revealing example of all) – occupy a

vital and central place in the totality of his life’s work. Moreover, with the conspicuous exception of André Gervais’s book, very little commentary or explication has ever been devoted to Duchamp’s verbal creations, while most of his visual creations have been analyzed to a level of detail and argument usually reserved for sacred writ. (Gervais’s own book uses a pun for its title, for La raie alitée d’effets speaks both of the homophonic “reality’ and the literal “line confined to its bed’ (raie alitée).)

Any analysis of puns and wordplays must begin by acknowledging the discouraging fact that the entire genre has been relegated to a particularly low status by self proclaimed intellectuals. Many classic deprecations could be cited, but James Boswell’s famous damning with faint praise (from

his celebrated life of Dr. Johnson, first published in 1791) will suffice as an example:

|

I think no innocent species of wit or pleasantry should be suppressed; and that a good pun may be admitted among the smaller excellencies of lively conversation.

|

How, then, can this lowest form of humor, representing the most neglected (and presumably most minor) aspect of Duchamp’s oeuvre, possibly merit any extensive analysis or be regarded as potentially replete with insight?

Duchamp himself, however, seemed to rank his verbal punning as important, at least as a source for his own inspiration and an embodiment of his general procedures – so perhaps we should take him at his (admittedly always cryptic) word and explore the issue further. Interestingly, Duchamp himself quoted one of the standard indictments of puns (“a low form of wit”) in his most forthright statement on their importance in his work (as cited by Gervais from a 1961 interview with Katharine Kuh):

|

I like words in a poetic sense. Puns for me are like rhymes. … For me, words are not merely a means of communication. You know, puns have always been considered a low form of wit, but I find them a source of stimulation both because of their actual sound and because of the unexpected meanings attached to the interrelationships of disparate words. For me, this is an infinite field of joy – and it’s always right at hand. Sometimes four or five different levels of meaning come through.

|

II. Duchamp’s Verbal Creativity: Big Oaks and Little Acorns

I shall not, in this article, try to explicate all of Duchamp’s verbal creations, or to present a synthetic account of the intrigue or utility of wordplays in general. But this topic surely transcends nitpicking or particularism because most, and perhaps nearly all, of Duchamp’s verbal constructions – again, with the ghost pun as the best and richest example I know – embody a guiding principle that also illuminates his lifetime of visual work, and underlies his general concept of the nature of creativity itself. I shall present four Duchampian categories of wordplay, each explored across a full range of potential meanings as illustrated by three modes in four categories. But all these usages proceed from the single principle that tiny variations – whether of sound or of orthography, and often so small as to pass beneath our discernment in the usual human style of lazy

or passive reading – can generate enormous, and wonderfully interesting, differences in meaning. This central principle corresponds with the basic definition of “pun,” as given in the Oxford English Dictionary:

|

The use of a word in such a way as to suggest two or more meanings or different associations, or the use of two or more words of the same or nearly the same sound with different meanings, so as to produce a humorous effect; a play on words.

|

As an opening example, and to show the long pedigree and pervasive importance of punning in Duchamp’s own conception of his work, a rarely explicit comment in one of his interviews with Pierre Cabanne seems especially revealing. (I thank Charles Stuckey of the Kimbell Art Museum for pointing out this passage to me.) Here, Duchamp discusses the title that he gave to one of his most important early works, the predecessor (in a sense) to his Nude Descending a Staircase – Sad Young Man on a Train, or, in the relevant French original, Jeune homme triste dans un train.

Duchamp said to Cabanne: “The ‘Sad Young Man on a Train’ already showed my intention of introducing humor into painting, or, in any case, the humor of word play: triste, train . . . “Tr” is very important.” But why should the simple alliteration of “tr” for both the man (in his adjectival designation as sad, or “triste“) and the vehicle (“train“) represent anything more than a tiny bit of elegant care introduced to make a title just a bit more melodious, salient, or agreeable to the ear?

In the immediately preceding comment to Cabanne, Duchamp spoke of his attempts to depict “the successive images of the body in movement” in both the Sad Young Man, and in Nude Descending.He particularly emphasized how he wished to display the parallel movement

of the train and the man walking down the train’s corridor. He spoke of the Sad Young Man, completed in December 1911: “First, there’s the idea of the movement of the train, and then that of the sad young man who is in the corridor and who is moving about; thus there are two

parallel movements corresponding to each other.”

At an evidently basic level, Duchamp’s verbal alliteration emphasizes the parallel movement of both train and man in the same constrained direction – the train on its track, and the man along the same path, now represented by the corridor of the elongated car. We need no more depth of meaning to understand Duchamp’s alliteration of the triste man on the

long train as a small and careful integrative touch, the kind of “God (or devil) in the details” (different sources for this common quotation cite either the Lord or Lucifer) that permeates the work of nearly all creative people (however much they may deny the concept and speak only

of spontaneity, or even of randomness).

But I suspect that here, as with nearly all Duchamp’s punning, several additional, and probably conscious, levels of meaning can also be specified (after all, Duchamp himself spoke of four or five levels of meaning in the quotation cited previously). First,

why is the young man “sad” at all; I see nothing in the painting that intrinsically suggests any particular emotional state for the gentleman involved. Perhaps he became “sad” primarily to create the integrative alliteration of triste and train.

We may then continue this line of thought, both situationally for he must walk (within the corridor) the same line – that is, the same one-dimensional route of truly minimal flexibility for directional motion – that the train on the track must also follow. Such phrases as “one-track mind” and “straight and narrow” (in the pejorative rather than the original theological sense) indicate the frequent metaphorical linkage of limitation and one-dimensional movement. Moreover, the man cannot, by his walking (or even his running), add more than a small increment to the sum total of man plus train in the same direction.

Finally, as I learned from Le Robert (the French equivalent of the Oxford English Dictionary), several current usages of “train” – and, even more relevant, the original meaning as well – reinforce an equation with sadness and limitation. We tend to think of trains as rapid facilitators of our motion (at least where they work well in Europe or Japan). But the word long antedates our modern era of fast transport, and most of the original meanings suggest forced motion in a line. In fact, the etymology harkens back to the Latin trahere, to draw – that is, with the implication of entrained, or being pulled along (against one’s preferences), rather than a primary meaning of voluntary enhancement or acceleration! Robert begins its entry by stating (my translation): “In the earliest texts . . . it means ‘to force to go somewhere’ or ‘to pull someone along.'”

Finally, and this curiosity must have caught Duchamp’s fancy – for Duchamp loved and pored over dictionaries, so he probably encountered the example – an old French phrase, originally spelled tran–tran, arose as an onomatopoetic representation of a hunting horn, and acquired the meaning of a dull or enforced routine (“ya gotta get up, ya gotta

get up, ya gotta get up in the morning” – as the common “translation” of an army bugler’s reveille). Interestingly, the spelling then shifted to the homophonic train–train (beginning in the 1830’s), probably, or so Robert speculates, by transference to a new image

of enforced motion suggested by the invention of the railroad. How could Duchamp have resisted this verbal version of his favored double “tr” – especially as imposed by a quirky linguistic shift to a visual metaphor, based on public fascination with a newfangled invention, after

the old aural context had faded from memory.

III. A Classification For the Richness and Extent of Duchamp’s Word Games

The four categories that I shall discuss in a more systematic way – before treating the ghost pun as a summary of all the strategies for extracting large differences and striking conjunctions from small disparities (or from identities with alternate meanings) – include a wide range of bases for their common generation of humor. I claim no expertise in the extensive literature on the nature and sources of humor, but perhaps the most widely cited principle of “punch lines” invokes a sudden shift of expected context – as in the riddle: “What do you do to an elephant with three balls?” Answer: “Walk him and pitch to the rhino.” This joke rests upon a visual and functional shift (enhanced, of course, by some old fashioned sexual ribaldry, which, as they say, never hurts) – from a pitiful and anomalous elephant with an extra item of anatomy, to a worthy batsman recast as a runner on first base with a less fearsome hitter at the plate. The usual verbal counterpart of this “sudden shift” principle works by disparity between the minimal difference of sounds or letters and the maximal consequence of a quirky outcome or an extensive change of meaning generated by such a tiny alteration of input – as in the answer (a lame joke in this case, but illustrative of the principle) to: “What’s

another name for a New York wine cellar?” “A Knickerbocker liquor locker.”

Each of Duchamp’s four categories generates its humor by this principle of small difference cascading to large, quirky and unexpected effect. The categories span a wide range of linguistic possibilities – from visual rearrangement of letters, to aural likeness, to plays on differences between the names and sound values of letters, to the use of common verbal

roots for generating an extensive range of meanings along numerous routes of minor change. I will illustrate the potential range of each category by presenting Duchampian examples in three widely varying modes: interesting conjunctions yielding more than the sum of parts; direct contradictions between the two tiny differences; and “annihilations” (a special intensification

of the second mode), where one member of the contradiction annihilates the

other, directly and causally.

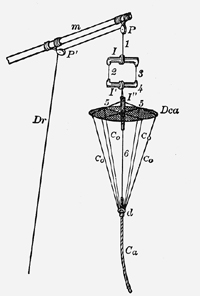

|

Click to

enlarge

|

|

|

|

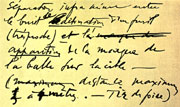

Marcel Duchamp,

Note 208, from Paul Matisse, Marcel Ducahmp: Notes, 1980

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

|

1. Anagrams, or extracting different meanings from the same letters rearranged in alternate sequences. This entirely spatial and visual category (for generating differences) represents a staple for fans of crossword puzzles and literary games. The sophisticated British style of crossword puzzle generally goes by the title “puns and anagrams,”

thus validating my separation of categories – for two types of punning,

or aural differences, will follow this visual category.

Mode One: Interesting Conjunction. As an obvious example of a fruitful anagram

that juxtaposes two arrangements of the same letters into an unexpected union and quirky context that Duchamp then exploited in a major work of his career – by turning the odd name into an actual product. Anemic Cinema may be reckoned as either puerile or powerful in execution, but the title is objectively anagrammatic.

|

Click to enlarge

|

|

|

|

Marcel Duchamp,

Note 237, from Paul Matisse, Marcel Ducahmp: Notes, 1980

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

|

Mode Two: Opposition. Silent et listen (P.N. number

208) .

Just rearrange the letters, and we can only do the latter in vain when

the condition of the former reigns.

Mode Three: Annihilation. I particularly like the following example as a resident in two categories: both a perfect anagram and a pun based on small aural differences between the two parts (category 2B to follow). Etrangler l’étranger (P.N., 237) – to strangle the stranger. Just move the “l” from the verb and make it the definite article for the noun. The action of the verb will then annihilate the noun. But the two parts of speech remain alike both visually (as a perfect anagram) and aurally (as a good pun).

2A. Puns as homonyms. If anagrams produce their large differences in meaning from spatial rearrangement of identical components (leading to a visual joke), then homonymic puns operate as a strict analog in the aural dimension – for the joke now arises from oddly disparate meanings generated by the same sounds (usually spelled differently or parsed into different words). The poor reputation of punning can largely be ascribed to childish efforts in this category, as in the American schoolboy’s joke: “What’s the difference between a place to drink and an elephant’s fart?” “A place to drink is a bar room, and an elephant’s fart is barroooooom!” Most “knock-knock” jokes also reside here, and their “ouch” records their status – as in “Who’s there?” “Petunia.” “Petunia who?” With the answer then given in song: “Petunia old grey bonnet . . .”

|

Click to enlarge

|

|

|

|

Marcel Duchamp,

Note 232, from Paul Matisse, Marcel Ducahmp: Notes, 1980

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

|

|

|

Click to enlarge

|

|

|

|

Marcel Duchamp,

Note 241, from Paul Matisse,

Marcel Ducahmp: Notes, 1980

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

|

|

Mode One: Interesting Conjunction. Duchamp created many puns in this most widely exploited category within the entire genre of wordplays. I confess that I don’t grasp the depth in some examples that must have pleased Duchamp because he repeated them so frequently, but

I may be missing some interesting innuendoes that would be apparent to a native speaker of French. “Un mot de reine; des maux de reins” (P.N., 241) contrasts “a word of the queen” with, literally, “kidney diseases,” but more generally and commonly, “backaches,” under a virtually identical pronunciation. (Perhaps, as a sexist crack, the pun means to identify forceless pronouncements from the boss’s subsidiary with “oh, my aching back.” Or perhaps as Sarah Skinner Kilborne, Toutfait‘s Senior Editor, suggested to me, backaches correspond to the queen’s word because pain speaks to us by giving us a word about body parts in trouble, while any statement from the queen also represents a word from the back — either negatively from the king’s annoying subsidiary, both literally and figuratively behind him, or more positively from his second in command, or backup.) Similarly, “my niece is cold because my Knees are cold” (P.N., 232) puzzles me as an apparently meaningless conjunction of different significations with nearly identical sounds, but perhaps our thoughts should turn to unconsummated incest (and perhaps they shouldn’t on the sensible principle that cigars and bananas are often just cigars and bananas. But why does Duchamp often capitalize only the word “Knees” of the male body part?).

I regard “head tax thumb tacks” (P.N., 272) as more satisfying (or perhaps only more personally comprehensible) because the use of a different body part as an adjectival modifier to the exact same sound (albeit represented by two distinct words of different spelling) yields such an interesting contrast of meanings – a form of taxation (popular in many European countries) based on fixed amounts per person (also, called a “capitation” from the Latin caput, or head), versus a humble bit of hardware pushed in by the stated body part.

|

Click to enlarge

|

|

|

|

Marcel Duchamp,

Note 272, from Paul Matisse, Marcel Ducahmp: Notes, 1980

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

|

|

Click to enlarge

|

|

|

|

Marcel Duchamp,

Nous Nous Cajolions, 1943

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

|

The potential richness of this otherwise somewhat

limited category of homonyms can be enhanced, as Duchamp so often does throughout his catalogue of wordplays, by combining both visual and aural versionsof the same image. In a lovely example, far more complex than I first realized, Duchamp drew a rebus in 1925 (Schwarz, number 412) for one of his oft-repeated homonymic puns: nous nous cajolions. Here, he breaks this full phrase

(“we flatter (or pet) each other”) into two visual parts – a woman caring for a child, representing a nanny (nounou in French, with the exact same pronunciation as nous nous), followed by the more obvious lion behind bars (cage au lion, or lion’s cage, pronounced exactly as

cajolions).

I only appreciated the depth

of Duchamp’s construction when I studied the etymology of cajoler in Robert. The probable origin of this verb, meaning to flatter or to wheedle, can be traced to the singing of birds in a cage. Moreover, the derived noun cajolerie specifically identifies the condescending tone that men often adopt in trying to influence women or children. Hence, both images of the rebus specify a historical source for the full phrase thus represented – the woman and child of the first part, followed by the caged animal of the second part.

|

Click to enlarge

|

|

|

|

Marcel Duchamp,

Objet-Dard, 1951

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

|

Mode two: Opposition. I suspect that Duchamp called his late and evidently phallic structure “Objet dard” because the piece both looks like a dart (or just to mark the word’s membership within the large set of nicknames for a penis), and also stands in opposition to the retinal style of conventional “fine art” that perpetually strives to fashion an “objet d’art” of the same pronunciation. However, for Duchamp’s best products in this mode, I nominate, for first prize, “do shit again and douche it again” (P.N., 232) as truly identical soundings with opposite meanings foul it again vs. wash it again); and, for second prize, the delicious bilingual homonym (P.N., 229) “coup de gueule / good girl” (a smack in the face and a well behaved lass – pronounced almost identically, with he first sounding like the second spoken with a French accent, despite the difference in meaning and orthography in the two languages).

|

Click to enlarge

|

|

|

|

Marcel Duchamp,

Note 229, from Paul Matisse,

Marcel Ducahmp: Notes, 1980

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

|

Mode Three: Annihilation. Duchamp frequently split “literature,” the aspiration of all wordplaying, into three separate words of nearly the same pronunciation “lits et ratures” (P.N., 224). But these words would annihilate any pretense to creating great written works, for we use our beds (“lits”) for the two most frequent activities, sleep and sex, that steal time from our literary struggles – while “ratures” are erasures!

2B. Puns as transpositions (near homonyms). This category encompasses the more subtle and systematic near homonyms (large differences in meaning generated by small alterations in sound) that generally win more respect than truly homonymic puns because they often originate by careful and thoughtful construction, rather than by the sheer accident

of an unconsidered alternative meaning for a chosen statement (or a consciously forced and painful likeness in the “ouch” mode of knock-knock jokes). However, some puns in this category, while also systematic in their structure, do arise unintentionally, and even win their humor for the embarrassment

thus created as a lapsus linguae (or slip of the tongue). The classics of this subgenre are called “spoonerisms” for their hapless eponym, The Reverend William Spooner (1844-1930), who apparently couldn’t help himself. Some spoonerisms have been traced to the source himself – as when the good Reverend confidently responded to a parishoner’s praise for his sermons: “many thinkle peep so.” Others, one suspects, have been purposely devised by legions of “admirers” and then attributed to the poor man – as in “a half warmed fish” masquerading as an imperfectly conceptualized desire.

|

Click to enlarge

|

|

|

|

Marcel Duchamp,

Note 224, from Paul Matisse, Marcel Ducahmp: Notes, 1980

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

|

I don’t know any common English distinction between these two types of puns (homonymic and transpositional), but the French language, while using “jeu de mots” (word game) as the vernacular term for puns in general, does make a formal separation with two less common words that also attribute greater value to the transpositional category. Robert defines calembour as a “witticism based on words that have a double meaning, or an ambiguity of words [forming] phrases that are pronounced in an identical manner.” But Robert then specifies the lower status of a calembour by recognizing an expansion of meaning that began in the early 19th century: “By extension, it means a poor pun (un mauvais

jeu de mots).”

By contrast, Robert defined a contrepèterie as “an inversion of two sounds (vowels or consonants) between two words transforming the meaning of a phrase, generally in a scatological direction.” From this original 15th century meaning, Robert then reports an extension of sense to the full category that I have called “transpositional” – with a clear implication of higher value: “The word designates a permutation of sounds, letters, or syllables in a phrase, in such a way as to obtain another phrase with a droll meaning.” Interestingly, Robert gives two hypotheses for the derivation of contrepèterie: either from the verb péter (to make a blast, more specifically to fart – as in a common phrase that many English speakers use in ignorance of its etymology – to be hoist by one’s own petard), thus meaning, literally, a backfire; or from pied (a foot) in reference to the “counter foot” or other meaning of the phrase. In any case, Duchamp uncorked a set of eminently worthy contrepèteries in all three modes:

|

Click to enlarge

|

|

|

|

Marcel Duchamp,

Note 231, from Paul Matisse, Marcel Ducahmp: Notes, 1980

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

|

Mode One: Interesting Conjunction. Among several that could be cited, two Duchampian concoctions especially intrigue me for their complexity of difference obtained by transposing a single sound between two words in a phrase. In the first example, Duchamp asks why a baby at the breast may be compared with first prize in a vegetable contest (P.N., 232): “Le premiere est un souffleur de chair chaude et le second un chou-fleur de serre chaude” – literally, “the first is a blower of warm flesh and the second a cauliflower from a hothouse.” The contrast in meaning is wonderfully absurd, but not without some amusing similarity in the great difference – as both cited items are round and warm (the baby’s head and the hothouse

cauliflower). But the pronounced alteration of meaning arises entirely from a small reciprocal shift in a pair of similar sounds – “s” and “ch” (pronounced “sh”) – in two words: for souffleur becomes chou-fleur, changing s to ch, while, later in the phrase, chair becomes serre, changing ch back to s.

|

Click to enlarge

|

|

|

|

Marcel Duchamp,

Disk Inscribed with Pun, from Anémic Cinéma, 1926

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

|

If the first example links two entirely different phrases by a similarity in form (warm round objects), the second describes a functional union in the sexual mode favored by contrepèteries. Duchamp labels this pun as a “question of intimate hygiene”: “Faut-il mettre la moelle de l’épée dans le poil de l’aimée” (from the 1939 pamphlet of Duchampian

aphorisms, Rrose Sélavy, and in P.N., 231 in a slightly different version) – an interesting and partly metaphorical description of copulation from a male point of view: “is it necessary to put the pith of the sword into the fur of the (female) beloved.” Again, the change of meaning arises from a single reciprocal transposition – m for p – between

two words: “moelle de l’épée (pith of the sword) and “poil

de l’aimée” (fur of the beloved).

Interestingly, Duchamp improved the pun (both in sound, objectively, and in meaning, in my opinion) when he changed poil (fur) to poêle (oven, and a better rhyme with moelle) in recycling this phrase on an anemic cinema disc (Schwarz, number 421).

|

Click to enlarge

|

|

|

|

Marcel Duchamp,

Note 249, from Paul Matisse, Marcel Ducahmp: Notes, 1980

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

|

Mode Two: Opposition. The same kind of simple transposition can also yield two phrases of opposite meaning. In one example, the transposition of c and l converts an order to cease singing into a command to permit this particular song (P.N., 249):

|

cessez le chant (stop the song)

laissez ce chant (leave this song)

|

In another case, number 254 of the Posthumous Notes, and labeled a “devinette” (riddle) by Duchamp, a more complex rearrangement of four syllables or combinations of syllables (rien, de, véné, and rable) highlights an opposition between something both honorable and persistent (venerable) and a mode of destruction in disgrace (râble de vénérien). André Gervais notes that we may also consider this form of wordplay as an anagram of syllables rather than letters:

“He has nothing venerable, but a back of a person with a venereal disease.”

|

Click to enlarge

|

|

|

|

Marcel Duchamp,

Note 225, from Paul Matisse, Marcel Ducahmp: Notes, 1980

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

|

Mode Three: Annihilation. In a wonderfully complex transposition, involving both sounds and letters (P.N., 225, and as a slight variant, appearing in the form cited here, in the 1939 booklet, Rrose Selavy, that collected 43 Duchampian aphorisms, most published previously and singly), Duchamp inverts the cr-s of a word in the first phrase (crasse) into s-cr in the corresponding word of the second phrase (Sacre). He then inverts the t-m and p-n of a word in the first phrase (tympan) into p-n followed by t-m for a word in the second phrase (Printemps). The result becomes a mordant comment about a famous incident in the long history of public opposition to avant-garde works of art – the angry crowd reaction (including prolonged catcalling and even some throwing of chairs) that followed the premiere of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring in 1913: “La crasse de tympan et non le Sacre de Printemps” – “The filth of the eardrum and not the Rite of Spring.” The mocking crowd annihilates Stravinsky’s piece by transposition to an ultimate affront upon their aural receptors; (an opponent might also nullify the composition by plugging up his ears so completely that no sound can get through).

####PAGES####

|

Click to enlarge

|

|

|

|

Marcel Duchamp,

L.H.O.O.Q., 1919

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

|

3. Alternatives. In a quite different concept for producing humor by the same effect (the drawing of two disparate meanings from identical or highly similar starting points, either visual or aural), Duchamp sometimes exploited the dual possibilities of a word’s orthography – first, the usual mode of assigning sound values to each letter and reading the resulting word or combination; and second, the generally unintended, but fully sensible, strategy of pronouncing the names of the letters sequentially to form a sentence or statement – a clever play on the very notion of literacy, for our visual representations of speech (at least in alphabetical systems) must both possess names concretely (or we couldn’t identify them to teach spelling) and represent sounds symbolically (or we couldn’t use them to read words). At least two of Duchamp’s works bear titles that exploit this duality: most notably the L.H.O.O.Q. (1919) inscribed at the bottom of his mustachioed Mona Lisa, and suggesting the near English reading of “look” but obviously intended primarily to designate the meaning rendered by the names of the letters in their French pronunciation: el-hache-o-o-ku, or “elle a chaud au cul” (she has a hot ass). Another piece, entitled M.E.T.R.O. and done as a prospective cover for an architectural magazine named “Metro” (for public transportation), also honors brave men – “aimer tes héros,” (to ove your heroes). Although these uses have been well recorded, Duchamp’s larger exploration of this category has not been extensively reported

because he published few of his other efforts, and most remain as jottings in the Posthumous Notes.

|

Click to enlarge

|

|

|

|

Marcel Duchamp,

Aimer tes héros, 1963

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

|

(I also suspect that he felt less satisfied with his products in this difficult category, and refrained from publishing most of his jottings because he remained unhappy with their only approximate renditions of the intended dualities, as several of the following examples will show. I also admit that some of my own interpretations in this category

must be regarded as more tentative and conjectural than the clear meanings of most cases in the other three categories).

Mode One: Interesting Conjunction. I will confess upfront to a conjectural reading in this case, but I was intrigued by a statement in the Posthumous Notes (number 248) linking the Mona Lisa to a striking visual image:

|

LHOOQ

Elle a chaud au cul comme

des ciseaux ouverts

|

(LHOOQ / she has a hot ass like / open scissors).

|

Click to enlarge

|

|

|

|

Marcel Duchamp,

Note 248, from Paul Matisse, Marcel Ducahmp: Notes, 1980

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

|

Perhaps Duchamp intends nothing more than the conjunction of two visual images of female sexuality – a hot ass and the obvious comparison of open scissors to a woman with legs spread apart. But I wonder – especially since Duchamp wrote LHOOQ, the letter version of the famous Mona Lisa statement, in the first line – whether he also wished to suggest the closest letter approximation to “des ciseaux ouverts,” the admittedly imperfect (but not

so bad) DCOUVR (close to découvrir, or discover (or, better yet, uncover), and missing only the “z” sound from ciseaux). If so, the conjunction’s double meaning becomes reinforced in both comparisons – the hot ass and spread legs of the full phrases, and the “look” and “uncover” of the corresponding letters read as single words.

|

Click to enlarge

|

|

|

|

Marcel Duchamp,

Note 240, from Paul Matisse, Marcel Ducahmp: Notes, 1980

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

|

Mode Two: Opposition. Duchamp played extensively with bilingual puns. Among his many jottings in this category of alternatives (letters read as a single word vs. letters read individually by their names), I note several, probably not accidental given his evident pleasure in the duality (as best shown in the M.E.T.R.O. piece), that work as examples of opposition in two senses of meaning and language (read as a single word in one language vs. read as a sequence of letters in French). Two of these (Latin vs. French) appear together (among other items) in number 240 of the Postumous Notes, thus reinforcing my conjecture of common

intent:

|

Click to enlarge

|

|

|

|

Marcel Duchamp,

Note 266, from Paul Matisse, Marcel Ducahmp: Notes, 1980

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

|

The first, “to erase” by letters read sequentially in French states the opposite command “make” (“fac“) as a single Latin word; while the second, “enough” in French reading, asks for more as an opposite Latin word (“ac” meaning “and”). I would also add an English example from the Posthumous Notes (number 266): “j’ai été and GET” – or “I have been” in a French statement about something already done, contrasted with the English command to do something now, or “get.”

Mode Three: Annihilation. I make my biggest stretch in this case (P.N., 266), but the following jotting intrigued me:

The comparison is admittedly imperfect (for one must move the “v” from second to fourth position as AKQVIT) – but if one drinks too much schnapps (aquavit, literally water of life), he will annihilate all potential for functioning with precision (avec acuité).

4. Generations and Compressions. My final category of wordplay evokes yet another, and quite different, principle used for the same purpose of constructing major disparities from homonyms or minor differences. Many words embody great potential for spinning out a wide range of meanings from a common source – both because the word itself may bear several alternative definitions, and also because the same word, in different combinations or used in different parts of speech, attains several contrasting significances. For example, an old English joke displays the full range for one of our most flexible and pungent words: A ship’s captain asks a sailor with no great mechanical expertise to go below and find out why the engine has stalled. The man descends, and finally emerges from the engine room with the following fully comprehensible diagnosis made of an exclamation, an adjective, a noun and a verb: “Fuck, the fucking fuck is fucked.”

For this category, I identify two different modes (from those cited in my discussion of the other categories), each linked to the most obvious physical structure of the wordplays:

|

Click to enlarge

|

|

|

|

Marcel Duchamp,

Note 252, from Paul Matisse, Marcel Ducahmp: Notes, 1980

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

|

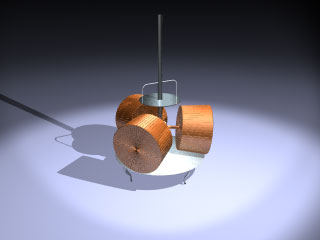

Mode One: Generations to Expand Meaning. The nonsense phrase of posthumous note number 252 provides an excellent, albeit nonsensical, example of this conceit in wordplays – four oddly conjoined and very different meanings (a verb linked with three unrelated nouns for a person, an object and a place), but all represented by virtually the same sound: “Le Sommelier a sommeillé sur un sommier lié de Somalie” – the wine steward (sommelier) napped (sommeillé) on a tied spring mattress (sommier lié) from Somalia (Somalie).

More significantly, Duchamp made a lovely conjunction between this verbal play in generating several meanings from a single source, and the visual action in one of his most interesting optical creations – the Rotary Demisphere (now on display in working condition at MOMA) that produces the appearance of an outwardly cascading spiral

as the device turns. (Interestingly, this effect is an optical illusion, for the actual piece consists entirely of concentric black and white circles. But the varied spacings and widths of these circles yields a spiral effect in rotation). On the edge of this rotary disc, carefully inscribed in elegant industrial perfection, Duchamp wrote one of his favorite, and oft repeated,

generative puns: “Esquivons les ecchymoses des Esquimaux aux mots exquis” – let us avoid the bruises of the Eskimoes in exquisite words. The text may sound ridiculous, but the pun becomes complex and clever through its union of similar sounds with different spellings. In the four generated phrases of nearly identical sound (esquivons, ecchymoses, Esquimaux and, with inverted syllables, mots exquis), the common sound moze receives different spellings in each of the three words (moses, maux, and mots); while the other nearly common sound of all four words uses three permutations of the first part (es, ek, and eks) with a constant second part (key) – Esquimaux as es-key, ecchymoses as ek-key, and exquis as eks-key. Moreover, and to show Duchamp’s care in detail, moze becomes the identical sound of three words only because, in two cases, an elision to the following word (Esquimaux

aux, and mots exquis) triggers the voiced “z” of moze in a word that would, if standing alone, be pronounced moe.

|

Click images

for videos (QT 0.3MB)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Marcel Duchamp, Rotary Demisphere,, 1925

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

|

|

Click to enlarge

|

|

|

|

Marcel Duchamp,

La Bagarre d’Austerlitz, 1921

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

|

Finally, expansions can be constructed in a

more subtle manner to accrete meaning by simply adding a few letters to the first meaning, and not by generating an entirely new word. The two phrases may then achieve an intriguing and meaningful conjunction – as in Duchamp’s clever title (not always fully appreciated) for one of his better known

works: Bagarre d’Austerlitz (also in P.N., 272). A bagarre is a brawl – and Napoleon won one of his most important battles at Austerlitz. Moreover, a major Parisian railroad station (gare) honors this victory – so the station (officially named Gare d’Austerlitz) commemorates the slightly longer battle, or bagarre d’Austerlitz. (The pacifist in me then yearns to add the Scroogian “bah, humbug” to all the vainglories of military honorifics). Truly finally, and looking forward to the next category, expansions of this kind can also be read in reverse as contradictions – the reduction of a great victory (sardonically called a brawl, or bagarre, in this case) to a memory embodied in a railroad terminal (a gare).

Mode Two: Contractions to Compress and Enhance Meaning (portmanteau words, in Lewis Carroll’s famous coinage). We have seen, throughout this catalogue of examples, how Duchamp loved to combine the visual and aural significance of his creations. This fourth category embodies the most explicit use of this principle, as a visual geometry of expansion or contraction becomes linked with the verbal significance of extended and compressed meanings. In the first, more obvious, mode of this category, we have just noted how visual expansions if a single word (shown even more dramatically in motion as an enlarging spiral in the Rotary Demisphere) can generate a growth in meaning as well. The opposite mode of contraction – overlapping two phrases into one by sharing several letters – need not join the two ideas conceptually. But Duchamp’s clearest examples of this more subtle mode do link visual compression with conjoined meaning. For example, he signed a letter, written in November 1921, soon after creating his feminine alter ego Rrose Sélavy, “Marsélavy” – obviously fusing his male and female personae by sharing the middle three letters “sel” (pronounced, at least without the accent aigu, just as the “cel” of his masculine name). In another more subtle example from the Posthumous Notes (number 241), Duchamp combines a diminutive testicle (orchidée) with a familiar French expression for inflexibility in thought – idée fixe, or fixed idea. The shared letters (idée) allows us to read the combined statement as a “fixed small

testicle,” thus merging two images for impotence – a small ball and an

unchangeable idea into an undersized nonworking sexual organ.

IV. The Ghost Pun as a Brilliant Epitome of All Categories

|

Click to enlarge

|

|

|

|

Marcel Duchamp,

Cover for “S.M.S.”, 1968

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

|

The preceding classification of Duchamp’s wordplays in four categories allows us to explicate the richness of the 1953 ghost pun. In short, and summarizing why I regard this deceptively simple statement as the richest of all Duchampian literary creations, the ghost pun resides in all four categories simultaneously, each adding a level of significance and expanding the scope of an apparently trivial scribbling on a candy wrapper. (Duchamp evidently liked this creation, for he wrote the phrase again as the only entry on the otherwise entirely white back cover of his S.M.S. portfolio design of 1968 (Schwarz,

number 654).

|

A Guest + A Host = A Ghost

|

In category one (visual as opposed to aural), this wordplay may be explicated as an anagram of a complex kind – combining selected letters (some common to both and others unique to one) of two words, while rejecting others, to form a new and distinctive word that continues the process of elimination in a different conceptual sense by turning the two inputs, conjoined in a reciprocal relationship, into their negation.

I will return to Category 2A of homonymic puns, for this meaning flows from something that I first noticed, and that served as the inspiration for this article. (Please forgive my conceit of saving my own contribution and potential discovery for a last word).

In Category 2B of transpositional puns (contrepèteries), we now encounter the verbal counterpart for the visual anagram of the first category. (Such wordplays often, and inevitably, feature both a visual anagram and an aural pun – as in Duchamp’s “étrangler l’étranger,” discussed above). The sound of the resultant “ghost” represents a small aural transposition of both inputs – guest by altering just one vowel sound (eh to oh), and host by changing the sound of the initial consonant (h to g, taking one step backwards in the alphabet).

In Category 3 of alternatives in reading words and sounding their letters, I confess my weak ground in the following conjecture, but I could not help wondering if Duchamp enjoyed the power that he gained in removing the “ue” of guest – that is, by taking these letters away in reading their French pronunciation (UÉ or, admittedly approximately, “away”) – and then substituting, with an exclamation of surprise (“oh“), the emptiness of zero or “o” to turn his living invitee into a shroud. (Or perhaps, having taken the ue of guest away, leaving g__st as a surrounding shell, Duchamp then followed a common instruction of commercial cooking products: “just add water.” Water, in French, is eau, pronounced just as the added letter “o.” Water, chemically, is H2O – exactly the added letters to “ghost,” with “h” in the second position).

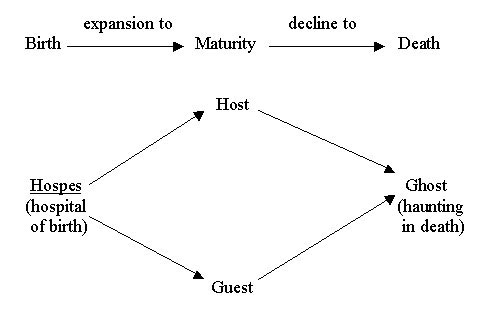

But when we consider Category 4 of Generations and Contractions, we can finally grasp the depth and interest of this otherwise trivial construction. With some admitted envy, I must credit André Gervais for recognizing, a long time before I discovered the same point ignorantly and independently (see page 208 of his book, La raie alitée d’effets), the status of this wordplay as both an initial expansion and a later contraction when considered etymologically. (Incidentally, this etymological point probably explains why Duchamp wrote the ghost pun in English for an exhibition held in Paris. The etymological argument doesn’t work in French, where neither of the two main words for guest will permit the wordplay – for hôte means both “guest” and “host” in French, so no duality arises from a single sound, whereas the other common term for “guest” (invitée) derives from a source with no etymological relation to the word for “host.”

In my previous discussion of Category Four, I argued that most contractions flaunt their meaning by intensifying the two fragments thus combined. But can an opposite significance – what I called “annihilation” in providing examples for each of my three other categories – ever be drawn, albeit paradoxically (for a cementing together would then destroy rather than reinforce the result), from a wordplay wrought by contraction? Classical portmanteau words always cement the two meanings – as in “smog” for smoke plus fog.

|

Click to enlarge

|

|

|

|

A statement page from

the advertising pamphlet for the ROSEWOOD HOTEL & RESORTS

|

The ghost pun represents the only example I know of a Duchampian creation in this deliciously paradoxical mode – but this added exegesis now requires a bit of scholarly sleuthing into the etymology of the three components. In modern usage, guest and host represent opposite aspects of a common functional pairing. One might even say that each word has little meaning without the other. (Interestingly, I spent a night in a Dallas hotel just after I had begun to write this article. An advertising pamphlet in my room quoted a statement from the honorary chairman of the board of Rosewood Hotels and Resorts, my hosts for the evening. The statement read in full: “Someone once told me that there are two kinds of people in the world – hosts and guests. Hosts take pleasure in making other people comfortable. Guests enjoy and appreciate what a good host has to offer.”) We may, indeed, regard guest and host as a duality that can achieve completion only by interaction.

We can now grasp the malicious irony of Duchamp’s verbal creation. By conjoining the words in a purely physical way, rather than by linking their meanings in a definitional manner, he produces an opposite result. Now the guest and host interact to annihilate each other (that is, to produce a ghost in their joining) rather than to fulfill their shared destiny in interaction! In other words, Duchamp has created

a contraction where the definitional result (a ghostly output that annihilates the two living inputs) reinforces the eliminations of letters required to construct the physical result – whereas most contractions yield the opposite effect of compressing two parts into a mutually intensified meaning.

The etymological observation now brings the irony to full realization. (And I assume that Duchamp – an inveterate and careful student of dictionaries – must have encountered this point, which probably provided his initial impetus for inventing this wordplay in the first place). “Guest” and “host” not only sound and look alike, but they also share the same etymological root, despite their later evolution to contrasting aspects of the same concept. Both words originated from the Latin root hospes, from which we also derive such words as hospitality (the shared concept uniting a guest and a host) and hospital. Thus, the ghost pun runs through a full life cycle – beginning as an expanding generation in the first mode of my fourth category, as the original and common root branches (from its birth, perhaps in the hospital of its etymological origin) and then growing in two directions to generate guests and hosts. Duchamp then brings the life cycle to its close in death – thus infusing the entire design with a lovely and dynamic symmetry – by fusing the two words together again (a contraction in the second mode of my fourth category, achieved by a physical amalgamation of letters rather than by a functional union of meaning), and killing both parts in the ghostly conjunction!

Let me then, and finally, return to my category 2A of homonymic puns, and to my own addition to this expanding exegesis, now extended to all categories. The most interesting and confusing of all linguistic ambiguities may well reside in the category of perfect homonyms – that is, identical words of exactly the same spelling and sound, but derived from different roots, and expressing different meanings. (Biologists like myself refer to this phenomenon of striking similarity, evolved independently from entirely different sources, as “convergence.” But persisting between the two versions of such striking similarity – the hair, rather than the feathers, on a bat’s wing, otherwise aerodynamically indistinguishable from a bird’s wing, for example. But how can we identify a convergence so perfect and complete that the two independent products become absolutely identical – as in homonymic words of the same spelling and pronunciation? Now, we simply cannot make the distinction from the products themselves. We can only recognize the difference if we find enough historical evidence to trace the identical products back down their independent lineages to their distinct origins.)

My favorite example of a complex and perfect set of homonyms derives from a mnemonic poem found, along with so many others, in schoolbooks for teaching Latin to past generations of students. The thrust of this example has been greatly enhanced by Benjamin Britten’s setting of the verse as the dominant leitmotif (with a stunningly sweet but utterly eerie tune) for his masterful chamber opera based on Henry James’s famous story: The Turn of the Screw. (For example, the tune sounds one last time to end the opera as the boy Miles falls dead on the stage). The verse teaches students four completely independent meanings (and derivations) for the single Latin word malo:

|

Malo: I would rather be

Malo: in an apple tree

Malo: than a naughty boy

Malo: in adversity

|

The poem rhymes and scans well, but its (admittedly minor) cleverness lies mainly in the fact that each set of words following “malo” provides a fully accurate translation for one distinctive root and meaning of this multiply convergent perfect homonym – malo as the first person singular of the verb malle, to prefer; malo as the ablative of the noun malus, an apple tree; malo as a masculine singular form of the adjective malus, meaning bad; and finally, malo as the ablative of the noun malum, or misfortune.

As noted by Gervais, and as argued further above, the cleverest features of the ghost pun must be exemplified within the contraction principle of category four – that, by their conjunction, the host annihilates the guest to generate the resulting emptiness of a ghost. The etymological argument – that Duchamp’s physical conjunction closes a life cycle of birth, growth, decline and death, by mimicking the original status of the two words as descendants of a single root – strongly intensifies the irony of annihilation.

As a final argument for the richness of Duchamp’s little conceit, I now add, from the homonymic category 2A, the additional etymological observation that the English word host includes, under its umbrella of identical spelling and sound, three entirely distinct words of fully independent origin – and that an aspect of each independent host annihilates a guest into a ghost! The meaning that ties host to guest in true etymological and evolutionary union must be regarded as primary (as discussed above), but the two additional definitions and origins for host could not have eluded, and must have delighted, Duchamp as well.

1. An entirely different word host derives from the Latin hostis, and may designate a crowd or, usually and more specifically, an army – not a friendly bunch, as the most common cognate “hostile” suggests. Most native speakers of English probably do not realize that several common usages of “host” – ranging from such vernacular phrases as “a host of troubles” to two common biblical sources described in the next sentence – derive from this distinctively different meaning, and not from the host who grants hospitality to a guest. In the King James Bible, host sometimes designates a crowd in neutral fashion (usually applied to angels and other astral beings in the “heavenly host”) – as in Luke’s

nativity story (2:13): “And suddenly there was with the angel a multitude of the heavenly host.” But the most common Biblical invocation – the frequent translation of one of God’s Old Testament names as “Lord of Hosts” (an English version of the Hebrew Yahweh Ts’baoth) – specifically designates the leader of a fighting force, the God of armies or battles (translated in the Latin Bible, the Vulgate, as Dominus exercituum, literally Lord of the armies).

In short, this second kind of host designates an

opposing army that will certainly, and with maximal efficiency, turn any

guest of the other side into a ghost.

2. Yet a third meaning of host derives from another completely independent word – hostia, meaning a victim or a sacrifice. An archaic English usage applied the word to Jesus, for obvious reasons reflected in the gospel stories of his death. This meaning persists in modern theological usage as the bread or wafer taken at communion, and regarded by Catholics (Duchamp’s background, of course) as the transubstantiated body of Christ, representing his sacrifice for us. If a guest at my church takes the host at communion, he achieves closer contact with the Holy Ghost who is one (in the trinity) with God the Father and Christ the Son.

V. A Closing Thought

The richness of the ghost pun, still imperfectly tapped, epitomizes Duchamp’s fascination with wordplays, or verbal creations, not only for their unity in concept and execution with his visual productions,

but also for explicating his integrative ideas about human creativity in general, as best embodied in his concept of the infrathin – that effectively invisible plane of separation, through which all products of human brilliance must pass in their transition and promotion from the tiny and palpable into wondrously diversifying realms of ever expanding meaning and signification. What better illustration than the humble and neglected wordplay that transforms a tiny and almost risible difference into a marvelously evocative cascade of ever diversifying meanings?

In this important sense, I think, the wordplay joins the readymade to fuse the central principle of Duchamp’s art, and of intellectual life in general: seek the richness that the human mind can extract from every item in our endlessly complex universe, even from things so apparently coarse or trivial – the mass-produced industrial tool or the crude and silly wordplay – that they pass beneath the notice, or fall under the active contempt, of most people. Keep your eyes and ears – and your mind – open, for the world does lie exposed in a grain of sand, and heaven in a flower. One might even make the principle more practical and partisan by privileging the humble and the despised as even more worthy than the showy and mighty – the belief of all revolutionaries, both in politics and art. For the last shall be first, as Jesus said, while Mary’s great effusion of thanks to God (the Magnificat of Luke, chapter 1) praised him most for this geometric and moral reversal: deposuit potentes de sede et exaltavit humiles (he hath put down the mighty from their seats, and exalted them of low degree).

I have read (but not been able to confirm) that the candy wrappers bearing the ghost pun at its original appearance in 1953 surrounded a chunk of caramel. If so, then even the first version gave each recipient an inside essence to chew on, something to sink one’s teeth into.

And so the ghost of Marcel Duchamp, the ultimate (and arrogant) Cartesian rationalist, covering his consummately intellectual ass in a nihilistic shroud of Dada, laughs at us as he urges both his fans and enemies to envelop his sweet little jokes in sharp and multiple layers of meaning.

Notes

1. To avoid inevitable confusion, I need to state up front that I am using the term “pun” in the expanded and generic sense now most frequent in vernacular American speech – that is, as a synonym for wordplays of any sort – and not in the original, restricted and more technical meaning of a particular form of wordplay based on different meanings from the same (or very similar) sounds of words. Webster’s Third New International Dictionary lists both meanings in sequence, with my general usage following the more specific sense: “the humorous use of a word in such a way as to suggest different meanings or applications or of words having the same or nearly the same sound but different meanings: a play on words.” In particular, by referring to the featured item in this article as “the ghost pun,” I obviously intend the generic meaning, as I attempt to show how Duchamp’s single phrase includes aspects of all major styles of wordplay. 1. To avoid inevitable confusion, I need to state up front that I am using the term “pun” in the expanded and generic sense now most frequent in vernacular American speech – that is, as a synonym for wordplays of any sort – and not in the original, restricted and more technical meaning of a particular form of wordplay based on different meanings from the same (or very similar) sounds of words. Webster’s Third New International Dictionary lists both meanings in sequence, with my general usage following the more specific sense: “the humorous use of a word in such a way as to suggest different meanings or applications or of words having the same or nearly the same sound but different meanings: a play on words.” In particular, by referring to the featured item in this article as “the ghost pun,” I obviously intend the generic meaning, as I attempt to show how Duchamp’s single phrase includes aspects of all major styles of wordplay.

2. Duchamp presented most of his wordplays in several different places (and sometimes in different versions), both in publications and private notes. I have not tried, in this article, to list and collate all the uses. In most cases, I will only cite the version first presented in the most comprehensive source, the Posthumous Notes (abbreviated P.N., followed by the number of the note as given and reproduced in Marcel Duchamp, Notes, arranged and translated by Paul Matisse (although I will work from the French originals), with a preface by Pontus Hulten, and published in 1980 by the Pompidou Center in Paris. When another source is relevant to my arguments (the Schwarz Catalogue Raisonné, for example), I will cite this version in my text as well. 2. Duchamp presented most of his wordplays in several different places (and sometimes in different versions), both in publications and private notes. I have not tried, in this article, to list and collate all the uses. In most cases, I will only cite the version first presented in the most comprehensive source, the Posthumous Notes (abbreviated P.N., followed by the number of the note as given and reproduced in Marcel Duchamp, Notes, arranged and translated by Paul Matisse (although I will work from the French originals), with a preface by Pontus Hulten, and published in 1980 by the Pompidou Center in Paris. When another source is relevant to my arguments (the Schwarz Catalogue Raisonné, for example), I will cite this version in my text as well.

3. In his review of my first draft, André Gervais argued that “lits et ratures” should not be classed as a homonym because the full phrase, read in French, adds a “z” sound in eliding the first two words. I appreciate and acknowledge this point, of course, but continue to regard the splitting of “literature” into three words as nearly homonymic because I’m not sure that Duchamp wants us to read the three words as a coherent phrase. He is telling us, I think, that “beds” and “erasures,” as separate and unconjoined items, destroy literature. But Gervais also makes the fascinating point that the full phrase of three words, read in French, sounds like “lisez ratures,” or “read the erasures.” So perhaps he was also telling us to decipher the various crossings out of his notes, an effort recently accomplished, with remarkable results and new insights, by Hector Obalk and André Gervais. 3. In his review of my first draft, André Gervais argued that “lits et ratures” should not be classed as a homonym because the full phrase, read in French, adds a “z” sound in eliding the first two words. I appreciate and acknowledge this point, of course, but continue to regard the splitting of “literature” into three words as nearly homonymic because I’m not sure that Duchamp wants us to read the three words as a coherent phrase. He is telling us, I think, that “beds” and “erasures,” as separate and unconjoined items, destroy literature. But Gervais also makes the fascinating point that the full phrase of three words, read in French, sounds like “lisez ratures,” or “read the erasures.” So perhaps he was also telling us to decipher the various crossings out of his notes, an effort recently accomplished, with remarkable results and new insights, by Hector Obalk and André Gervais.

4. My praise, once more, to André Gervais, who always sees further into the richness of Duchampian wordplays. In his comment on my first draft, he points out that, in inverting tympan to Printemps, Duchamp adds a sound as well — the letter “r,” pronounced “air” and meaning “aria” or added music. What a lovely expansion of my suggested meaning: one adds music to the plugged eardrum that cannot hear, and one obtains Stravinksy’s great and challenging piece. 4. My praise, once more, to André Gervais, who always sees further into the richness of Duchampian wordplays. In his comment on my first draft, he points out that, in inverting tympan to Printemps, Duchamp adds a sound as well — the letter “r,” pronounced “air” and meaning “aria” or added music. What a lovely expansion of my suggested meaning: one adds music to the plugged eardrum that cannot hear, and one obtains Stravinksy’s great and challenging piece.

5. Another brilliant addition from André Gervais: if one follows the French instruction and erases the first letter from FAC, one still has AC, or “enough” (“assez“) — all of which reminds me of the famous French and English pun about the sufficiency of single things: un oeuf is enough (“one egg is enough”). 5. Another brilliant addition from André Gervais: if one follows the French instruction and erases the first letter from FAC, one still has AC, or “enough” (“assez“) — all of which reminds me of the famous French and English pun about the sufficiency of single things: un oeuf is enough (“one egg is enough”).

|

Click to enlarge

|

|

|

|

Marcel Duchamp,

Cover for “Le Dessin dans l’Art Magique“, 1958

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

|

6. In another combination of verbal and visual expansions (Schwarz, number 561), Duchamp drew a device for generating a bevy of French words by affixing different prefixes to the common ending mages (including images, cheeses (fromages) and injuries (dommages)). He depicts the prefixes as an ellipse surrounding the central mages – meaning “Magi” (wise magicians) when standing alone, and a fitting image for his catalogue cover to a show entitled Le dessin dans l’art magique. 6. In another combination of verbal and visual expansions (Schwarz, number 561), Duchamp drew a device for generating a bevy of French words by affixing different prefixes to the common ending mages (including images, cheeses (fromages) and injuries (dommages)). He depicts the prefixes as an ellipse surrounding the central mages – meaning “Magi” (wise magicians) when standing alone, and a fitting image for his catalogue cover to a show entitled Le dessin dans l’art magique.

7. Duchamp’s second use of the ghost pun (on the back cover of the 1968 S.M.S. portfolio) indicates that he conceived the major meaning of this wordplay as a contradiction in my fourth category – and that I am not forcing my own interpretation upon his concept in this exegesis. I am confident that he regarded wordplays in expansion and contraction as opposite modes of a common category – for he placed a reproduction of the anemic cinema disc with his favorite expansion pun (“esquivons les ecchymoses des Esquimaux aux mots exquis,” as discussed in Section III) on the front cover, while inscribing the back cover with his ghost pun: an expansion pun for the opening of a portfolio (to presage a forthcoming generation of a plethora of items from a single source), and a contraction pun (with the added meaning of annihilation) for the closing on the back cover! 7. Duchamp’s second use of the ghost pun (on the back cover of the 1968 S.M.S. portfolio) indicates that he conceived the major meaning of this wordplay as a contradiction in my fourth category – and that I am not forcing my own interpretation upon his concept in this exegesis. I am confident that he regarded wordplays in expansion and contraction as opposite modes of a common category – for he placed a reproduction of the anemic cinema disc with his favorite expansion pun (“esquivons les ecchymoses des Esquimaux aux mots exquis,” as discussed in Section III) on the front cover, while inscribing the back cover with his ghost pun: an expansion pun for the opening of a portfolio (to presage a forthcoming generation of a plethora of items from a single source), and a contraction pun (with the added meaning of annihilation) for the closing on the back cover!

8. As another example of correspondence between Duchamp’s verbal and visual creations, and as a further argument for the centrality of the ghost pun, I couldn’t help noticing that, in my fourth category of contractions, the resultant “ghost” represents a complex portmanteau word, as an anagrammatic amalgam of “guest” and “host.” In French, a portmanteau word is a “mot valise” – and Duchamp called the epitome of his life’s visual work a “boîte-en-valise.” So ghost, as a mot valise may be the verbal analog to his mostly visual boîte-en-valise. Two modes of immortality: a concrete and portable summary, and a permanent haunting by the most brilliant spirit of twentieth century art. Yes – pack all your work and troubles in your old kit bag (your verbal and actual valise), and smile, smile, smile! 8. As another example of correspondence between Duchamp’s verbal and visual creations, and as a further argument for the centrality of the ghost pun, I couldn’t help noticing that, in my fourth category of contractions, the resultant “ghost” represents a complex portmanteau word, as an anagrammatic amalgam of “guest” and “host.” In French, a portmanteau word is a “mot valise” – and Duchamp called the epitome of his life’s visual work a “boîte-en-valise.” So ghost, as a mot valise may be the verbal analog to his mostly visual boîte-en-valise. Two modes of immortality: a concrete and portable summary, and a permanent haunting by the most brilliant spirit of twentieth century art. Yes – pack all your work and troubles in your old kit bag (your verbal and actual valise), and smile, smile, smile!

9. Again, and one last time, my enormous thanks to the grand master of interpretation for Duchamp’s wordplays – André Gervais, who, in his very kind and lengthy review of my first draft, again caught something I had missed: caramel also yields the deliciously relevant anagram à Marcel, or “to Marcel.” 9. Again, and one last time, my enormous thanks to the grand master of interpretation for Duchamp’s wordplays – André Gervais, who, in his very kind and lengthy review of my first draft, again caught something I had missed: caramel also yields the deliciously relevant anagram à Marcel, or “to Marcel.”

|

|