Un Chapeau

Robert Lebel (5 janvier 1901–28 février 1986), écrivain, expert d’art (à partir de 1935) et expert en tableaux anciens près les tribunaux et les cours d’appels (à partir de 1953), est né et mort à Paris.

C’est à New York, à la galerie d’Alfred Stieglitz, An American Place, en juillet 1936 selon toute vraisemblance, qu’il a rencontré Marcel Duchamp, alors aux États-Unis afin de réparer le Grand Verre.

C’est encore à New York, à l’occasion de la Deuxième Guerre, durant l’exil forcé, qu’il a écrit “L’inventeur du temps gratuit”, vers 1943-1944, “à une époque où je voyais Duchamp presque tous les jours. Le titre Ingénieur du temps perdu date de beaucoup plus tard et je crois que Duchamp s’est inspiré de mon titre plutôt que moi du sien. Je lui avais montré mon texte peu après l’avoir écrit”. Ce “conte féérique et sacrilège en pleine civilisation du gratte-ciel et du métro aérien”(rabat de la couverture, édition de 1977) sera publié une quinzaine d’années plus tard en revue: Le surréalisme, même, Paris, nº 2, printemps 1957, avec trois photos de l’Elevated, justement , puis sept années plus tard en livre: La double vue suivi de L’inventeur de temps gratuit, avec un diptyque gravé à l’eau-forte par Alberto Giacometti et un pliage (La pendule de profil, 1964) de Marcel Duchamp, Paris, Le Soleil noir, 1964; ce livre a reçu le prix du Fantastique en 1965.

Enfin, c’est vers 1949 que Robert Lebel a le projet de consacrer un livre — biographie et catalogue — à Marcel Duchamp, livre auquel il travaille de façon élaborée du printemps 1953 à l’automne 1957 et qu’il complète et corrige en 1958, au moment de sa traduction en anglais. Ce livre, qui sera le premier livre, aura été précédé et suivi d’une vingtaine d’articles (sur Duchamp, mais aussi sur Picabia et Duchamp, de Chirico et Duchamp, Breton et Duchamp, Man Ray et Duchamp, etc.) parus à partir de 1949, justement, et qui n’ont pas tous été repris dans l’édition entièrement recomposée de 1985:

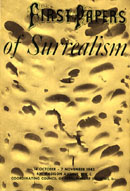

• Sur Marcel Duchamp, Paris, Trianon Press, 1959; traduit en anglais par George Heard Hamilton, New York, Grove Press, 1959; traduit en allemand par Serge Stauffer, Cologne, DuMont Schauberg, 1962;

• 2e édition, américaine augmentée, New York, Paragraphic Books, 1967; 2e édition allemande revue et augmentée, Cologne, DuMont Schauberg, 1972;

• Marcel Duchamp, 2e édition française revue et augmentée, bien qu’élaguée de son catalogue, de ses illustrations et de sa mise en page, Paris, Belfond, coll. “Les dossiers”, [septembre] 1985;

• réimpression en fac-similé de l’édition courante de 1959, augmentée sur feuilles volantes de 4 lettres de Marcel Duchamp à Robert Lebel, Paris et Milan, Mozzotta, et Paris, Centre Georges Pompidou, 1996.

Avec Francis Picabia (à partir de 1911), peintre et poète, Man Ray (de 1915), peintre et photographe, et Henri-Pierre Roché (de 1916), collectionneur et diariste, Robert Lebel aura sans doute été le dernier complice de Marcel Duchamp. “Tout en étant très amis, nous étions restés sur une certaine réserve” ainsi résumera-t-il, à la fin de sa vie, cette complicité.

André Gervais

9 avril 2000

A. Robert Lebel, lettre à André Gervais, Paris, 21 mai 1979. Ingénieur du temps perdu est le titre de la réédition, en 1977, des Entretiens avec Marcel Duchamp (1967) de Pierre Cabanne.

B. Dans un article sur Robert Lebel et Marcel Duchamp (Critique, Paris, nº 149, octobre 1959), Patrick Waldberg précise que “le brillant et curieux texte de Robert Lebel, L’inventeur du temps gratuit, véritable spéculation, au sens où l’entendait Jarry”, aurait pu paraître dans le Da Costa encyclopédique, preparé à partir de 1946. Et il ajoute: “On reconnaît sans peine, dans l'”inventeur” en question, sinon Marcel Duchamp en personne, tout au moins l’un de ses frères en esprit.”

L’inventeur du temps gratuit

par Robert Lebel

Tous les photos reproduit ici étaient publiée avec l’article original.

(Le surréalisme, même, Paris, nº 2, printemps 1957.)

Dès qu’il laissait derrière soi, vers la pointe de l’île, la silhouette mutilée déjà du terminus, l’Elevated pénétrait dans des rues étroites dont il frôlait les façades aux escaliers de fer. Front street, Pearl street qu’il recouvrait et calfeutrait comme de longs tunnels, ne menaient au-dessous de lui, dans l’intervalle de ses ébranlements, qu’une existence illusoire et silencieuse d’ancien décor. Scellées de volets imprenables ou aveuglées de crasse, les fenêtres avaient cessé l’une après l’autre de s’ouvrir. C’était, entre les docks de l’East River et les gratte-ciel de Wall street, l’étrange ville morte où tout ce que New York recelait de menaçant venait se terrer et attendre.

Ce quartier m’attirait et j’ai souhaité d’y vivre mais les maisons y étaient à ce point inhabitées qu’un locataire éventuel y faisait aussitôt figure de suspect. Personne ne voulait croire que l’on songeât sérieusement à s’établir dans ces bâtisses délabrées, à l’écart de tout ce que le zèle urbaniste proposait de dignité et de confort. En vain avançais-je l’excuse que je me donne volontiers d’être artiste. Cet argument qui est accueilli souvent avec indulgence ne provoquait ici qu’un surcroît de méfiance et d’hostilité.

Je n’en poursuivais pas moins mes démarches de porte en porte. La déception que j’éprouvais à me heurter inévitablement à de nouveaux échecs se trouvait amplement compensée par mes découvertes à l’intérieur des maisons que je visitais de fond en comble. J’y errais parfois deux ou trois heures sans rencontrer un être vivant. C’est au cours de l’exploration d’un immeuble qui me parut totalement abandonné que je lus à une porte l’inscription suivante, en français:

A. Loride, L’Inventeur du Temps Gratuit – Cela était écrit à la plume, négligemment, sur une feuille de papier fixée par deux clous.

J’avais déjà pu parcourir, aux autres étages, les bureaux d’une compagnie de navigation, l’atelier d’une imprimerie et un établissement de bains, tous également déserts. J’entrai donc sans hésiter. Il était trois heures de l’après-midi d’un jour ouvrable.

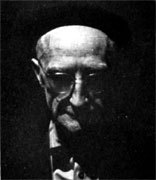

Au centre d’une sorte de vaste entrepôt extraordinairement encombré, un homme entièrement nu exécutait des mouvements de culture physique. Il se retourna et je constatai qu’il devait avoir dépassé cinquante ans, bien que son corps fût toujours assez svelte. Il était glabre et son apparence de méticuleuse propreté dans un tel milieu surprenait. Pourtant je fus surtout frappé par son absence d’embarras. Sans penser à se couvrir, à marquer son étonnement ou à justifier sa tenue, il me considérait avec calme et attendait mes explications.

Je ne trouvai d’abord, plutôt sottement que: “Etes-vous Français?”, ajoutant après un silence: “Je viens pour votre invention”.

click to enlarge

Cliquez pour agrandir

D’un signe, il me permit de m’asseoir mais, sauf un lit où était couchée une très jeune femme, on n’apercevait aucun siège et je m’appuyai contre une caisse, poliment. “Je vous écoute”, dit-il. “A ce moment, l’Elevated surgit au ras des fenêtres et tout se mit autour de nous à vaciller.”

“Monsieur,” lui répondis-je enfin, dès que l’on put s’entendre, “je ne vous cacherai pas que je m’intéresse prodigieusement à vos découvertes et c’est parce qu’il me tarde d’en discuter avec vous que j’ai omis de prendre, avant d’entrer ici, les précautions d’usage.”

˜Je ne reçois que sur rendez-vous,” répliqua-t-il brièvement. “Inscrivez votre nom et votre adresse (il me désigna un mur couvert de notes et de chiffres), je vous convoquerai” et, me tournant le dos, il se remit à sa gymnastique.

Sa lettre ne me parvint que trois semaines plus tard. Elle était rédigée sur une feuille à en-tête de A. Loride and Company. “Je vous préviens, écrivait-il, que je ne suis ni fou, ni mystique, ni philosophe, ni inspiré, ni poète. Je me livre à des recherches positives et mon activité correspond, dans une large mesure, au titre peut-être un peu trop affirmatif que je me suis décerné. Engagé dans une entreprise réelle, la nécessité pratique m’obligeait à lui donner une raison sociale. D’autres s’intitulent bien roi du pétrole ou pharmacien de l ère classe. Quoi qu’il en soit, nos rapports éventuels, permettez-moi de le stipuler, ne pourront être que strictement commerciaux. Je ne désire pas de nouveaux amis, mon excentricité ne regarde que moi et ce n’est pas sans intention précise que j’ai choisi, pour m’y retirer, un lieu où seules votre curiosité et votre extrême indiscrétion devaient vous emmener à me découvrir.” Et il m’assignait un entretien pour un jour suivant.

Je fis le chemin mas l’Elevated. A plusieurs reprises déjà, depuis notre première entrevue, j’avais tenté l’expérience de passer devant ses fenêtres, espérant le surprendre en quelque posture significative mais, du compartiment, s’il eût suffi de se pencher à peine pour frapper à sa vitre, on ne distinguait rien qui permit de soupçonner sa présence.

Il me reçut avec l’impassibilité que j’avais observée précédemment. Il n’était ni réticent, ni chaleureux. C’est armé d’une bonne grâce un peu lointaine qu’il se présentait à ce tête-à-tête dont, visiblement, il n’attendait mais aussi ne redoutait rien. Vêtu non sans recherche, il me guida courtoisement à travers un remarquable désordre de machines, d’établis, de poutres, d’horloges, de coffres-forts, jusqu’au lit qui n’était pas occupé.

“Vous avez beaucoup de matériel,” lui dis je pour amorcer la conversation. “Tout ce que vous voyez dans cette pièce, ou mieux dans ce magasin, y a été laissé par de précédents locataires,” répondit-il. “Vous n’y verrez donc pas grande chose qui m’appartienne, mais je préfère ces instruments de hasard. La diversité de leur nature m’interdit de me borner à un seul mode de réflexions et, dans ce laboratoire dont j’inventorie systématiquement et, bien entendu, à contresens les ressources, mon imagination s’expose moins à marquer le pas.”

“Mais le temps?” demandai-je.

“J’y venais puisque j’ai mis au point ma théorie grâce à la réunion toute providentielle devant moi de ces trois horloges dont une fonctionne avec exactitude, une autre irrégulièrement et la dernière pas du tout. De même, cette bascule m’a conduit à réviser mes vues sur le isotopes et je dois à cette essoreuse électrique des révélations inattendues sur la suspension pyrrhonienne.” Mais, rencontrant mon regard, il ajouta vivement: “Surtout ne me prenez pas pour une espèce de penseur. Je ne vise qu’à relier des notions éparses, je ramasse les miettes des grandes idées. Je hais les abstractions. Toutes ces machines, pour la plupart déficientes, me ramènent sans cesse aux détails, aux vérifications fragmentaires et m’astreignent à un bricolage mental d’une heureuse incohérence. Elles imposent à mon interrogation sa forme concrète tandis que leur caractère éminemment fictif me retient de céder, comme le font les physiciens et comme l’ont fait, malheureusement, tant d’alchimistes, au souci mortel du résultat. J’apprends ici à tirer inutilement parti du tout. Ainsi, le passage inéluctable de l’Elevated assume pour moi une fonction aussi fondamentale que le cycle des marées. Il exprime avec autant de perfection le piétinement humain mais, en outre, il a l’immense avantage de maintenir l’organisme dans un état d’exaspération latente. Le flux et le reflux ne nous incitent jamais qu’à nous résigner, alors que l’Elevated nous pousse directement à la révolte contre ce qu’on persiste à nous présenter comme notre condition.”

“Mais le temps?” insistai-je.

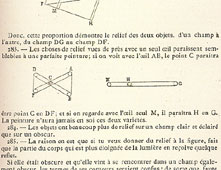

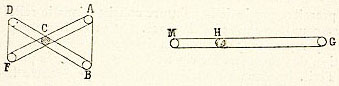

“Nous y sommes. Chacun de nous aspire à l’intensité d’une vie de chien, à ces journées bien remplies qui préludent traditionnellement à un repos bien gagné. Notre époque a beau jumeler en un culte dérisoire la liberté et le loisir, les êtres les plus satisfaits sont toujours les plus affairés, donc les plus asservis. Or il est clair qu’aucun progrès n’est à notre portée si nous ne surmontons d’abord la compulsion de l’activité utile. C’est cependant elle, et elle seule, qui continue à régir notre concept du temps. Tenez, fit-il en saisissant un bâton pour désigner les horloges, chacun de ces cadrans figure le temps sous un de ses trois aspects. Pour la quasi totalité des hommes, il n’en existe qu’un. Les individus dits évolués en pressentent peut-être deux, mais je suis un des rares à en définir explicitement le troisième, si bien que je puis, sans trop d’imposture, m’en présumer l’inventeur. Mon but, d’ailleurs, est moins de le formuler théoriquement que de lui donner une consistance. J’ai l’ambition d’en faire une véritable denrée, un simple objet de consommation et d’échange, au même titre que ces remèdes dont les chimistes sont seuls à connaître la composition, mais qui se vendent à tous les comptoirs. C’est pourquoi je me flatte d’être un commerçant et non un philosophe.”

click to enlarge

Cliquez pour agrandir

Il se tut, alla s’installer devant une machine qui se trouvait à proximité des horloges et, du pied, mit une pédale en marche. Bientôt, de minces baguettes de bois commencèrent à jaillir d’un orifice d’échappement. “Excusez-moi,” dit-il, “je dois satisfaire à une commande pressée.”

“Seraient-ce là vos comprimés de temps?” m’écriai-je. Je les eusse plutôt imaginés cristallins et sous les dehors de quelque pastille.

“Peu importe le symbole,” fit-il, tout en continuant à pédaler. “Il se trouve que, sans y être pour rien, j’ai à ma disposition cet appareil qui débite des rondins dont les quincailliers du voisinage, mes clients, se sont révélés avides. Un sculpteur surréaliste en ferait même, me dit-on, courant usage. Toujours est-il que cette industrie exige à peine de moi la somme d’attention dont je suis capable à l’égard de ce qui me fait vivre. Je puis m’y livrer sans quitter des yeux cette première horloge et, aussi aisément que, de cette même place, je vois venir, passer et disparaître l’Elevated, je vois, sur ce cadran, venir, passer et disparaître le temps qui ne s’interrompt jamais, le temps qui possède une valeur vénale. Ces aiguilles déjà vétustes tournent avec une régularité qui ne peut tenir que du prodige. Il semble que ce soit leur destin de tourner, quoi qu’il arrive. Leur bonheur consiste à n’être ni en avance, ni en retard, ni surtout arrêtées. On discerne dans leur mouvement net, résolu, sûr de soi, la satisfaction cocardière dont resplendit le visage de l’honnête serviteur, de la ménagère diligente, de l’ouvrier consciencieux, du fonctionnaire méthodique, de l’homme d’affaires entreprenant, de tous ces gens que je vois se bousculer le matin dans l’Elevated pour se rendre à leur travail, et s’y écraser de nouveau le soir pour regagner leur domicile. Or ce temps se déroule devant moi comme un film. Je sais, je sens que j’y suis étranger. Littéralement j’y échapper, mais serait-ce en vertu de mon horaire que l’on peut estimer fantaisiste? Je ne le crois pas. Comparez les physionomies que je vous ai décrites avec celles qui les remplacent aux heures que l’on nomme si justement creuses, lorsque les compartiments presque vides sont devenus à peu près confortables. Les privilégiés qui, pour des raisons généralement très douteuses, ont bénéficié d’une levée d’écrou, loin de se montrer ravis, paraissent, au contraire, pour la plupart, inquiets et tourmentés. Ils parcourent distraitement leur journal, ils se crispent nerveusement sur leur banquette, la lenteur des trains les irrite. En bref, leurs symptômes sont ceux d’une rumination morbide.”

S’interrompant soudain, il repoussa du pied les baguettes qui s’étaient accumulées devant l’orifice et il reprit sa manœuvre. “Rassurez-vous,” continua-t-il, “mes voyageurs des heures creuses ne sont aucunement dévorés de remords. Au surplus, la réaction du privilégié devant l’esclavage des autres se traduit plutôt par un cynique contentement. Non, l’explication est ailleurs. Si vous passiez comme moi plusieurs heures par jour à braquer vos lorgnettes sur l’Elevated du haut de cette chaire de prédicateur anglican (ce qui me permet de tout voir sans risquer d’être aperçu), vous pourriez constater que ces voyageurs se subdivisent en deux catégories bien distinctes. Simple problème d’interprétation que j’ai dû résoudre à la façon de l’ethnographe ou de l’anthropologue par une exhaustive confrontation des caractères individuels. Certains voyageurs que l’on surprend, aux heures creuses, à sourire, voire à se détendre, sont en réalité des membres provisoirement détachés de la grande fourmilière. Selon le langage des bureaux, ils sont en course ou, comme disent plus noblement les militaires, en service commandé. Leur sérénité, leur désinvolture, qui les différencient aussitôt de leurs voisins immédiats, n’ont pas d’autre origine. Pour eux, l’heure ne saurait être creuse puisque la société qui ne les perd pas de vue en consacre la densité. Le temps où l’usage a frappé une monnaie reste le lien même qui les rive à leur agitation.”

Tandis qu’il dégageait de nouveau les issues de son appareil, je me permis d’objecter: “Cependant, pour les autres voyageurs des heures creuses, ceux qu’à plus ample examen vous classez toujours parmi les oisifs véritables, comment expliquer leur mélancolie si vous écartez l’hypothèse de scrupule? Aurons-nous recours à l’exploitation banale de l’angoisse dont nos voyageurs sont supposés être saisis devant la perspective de leur disponibilité?”

˜Nullement,” répliqua-t-il avec un peu d’humeur. “Ce serait rendre à l’argument spécieux par excellence, celui dont on se sert communément pour justifier les inégalités sociales et démontrer le bien-fondé de la servitude en exagérant à la fois les responsabilités de l’oisif et les dangers que courrait un homme libre. Si les individus qui parviennent à une relative indépendance sont, de fait, les plus désemparés et les plus ombrageux, c’est que, physiquement affranchis, ils demeurent mentalement des esclaves. Ils ne rectifient pas leur conception du temps alors que celui-ci modifie pour eux son rythme. Dès lors s’introduit dans leur existence le déséquilibre que ces secondes aiguilles miment adéquatement. Elles ne sont plus animées que d’un mouvement erratique, fiévreux en quelque sorte et rompu par de longs moments d’immobilité pesante. Sans cesse, elles sont en avance ou bien en retard mais sur quoi, pourrait-on demander, puisque précisément c’est en dehors du circuit de la ponctualité qu’elles se situent? D’où vient cette inconséquence si ce n’est de la conscience très vive qu’elles conservent encore du temps social? En définitive, leur regret d’en être exclues l’emporte sur leur soulagement d’en être dispensées. Une horloge déréglée, donc libre, n’oublie pas l’horloge exacte qu’elle fut. L’heure qu’elle marque n’est jamais absolument délivrée de l’autre dont un timbre antérieur s’obstine à sonner le souvenir.”

click to enlarge

Cliquez pour agrandir

Sans quitter sa machine, il se prit à rire silencieusement.”Voyez-vous,” enchaîna-t-il, “je n’accepterais le titre de penseur que suivi de l’épithète comique, mais au sens non douloureux du terme et comme Stendhal envisageait de devenir “the comic bard”. Contrairement à Molière et à sa misérable suite de vaudevillistes, je ris moins de l’homme lui-même que des abstractions dont il est pénétré. Le comique de la pensée est beaucoup plus irrésistible que celui des caractères. Il est grand temps d’en finir avec la comédie classique et son arsenal de types à jamais flétris pour lui substituer une comédie de la connaissance qui se terminerait par un beau massacre d’idées, au lieu de conclure systématiquement par l’écrasement du “drôle”. Je vois fort bien, par exemple, une comédie sur la notion du temps, vielle coquette aux minauderies sordides, qui compte et recompte inlassablement son or à mesure qu’il lui glisse des doigts. Ce serait elle qu’il s’agirait de confondre et de rosser en lui laissant, comme il sied, sa configuration idéographique. J’aime souvent à croire que les formes surprenantes dont l’art moderne a été prodigue sont des idées qui ont pris corps et s’apprêtent pour la scène future où elles seront rouées de coups. Ce sont les personnages de notre nouvelle comédie et leur aspect, parfois repoussant à première vue, ne fait que confirmer leur signification mythique et annonce le sacrifice bouffon auquel ils sont destinés.”

Les piles de rondins avaient atteint une hauteurs considérable et, jugeant sans doute suffisant le résultat de son effort, mon hôte cessa de pédaler, se leva, désigna de nouveau la seconde horloge et reprit: “Ce temps qui a cessé d’être social et qui n’a pas encore commencé d’être individuel, ce temps amorphe, incolore, insipide, constitue un intolérable poids mort pour ce qu’on est convenu d’appeler l’évolution humaine. Ou bien celle-ci n’est qu’imaginaire et, parmi des masses éternellement primitives, nous ne représentons qu’une écume négligeable de dissidence, ou bien, dès son départ, cette évolution s’est engagée dans une impasse où elle butte à un obstacle qui la fait irrévocablement refluer. Mais qu’on y prenne garde, le désir même de liberté ne résistera pas indéfiniment au démenti terrible que lui infligent les faits. Entre les paroles que nous énonçons et notre comportement notoire, la brèche scandaleuse s’élargit chaque jour. Autour de nous, les défaillances se précipitent et les plus rebelles font parfois penser à ces femmes émancipées qui souhaitent secrètement un homme à poigne. Il ne leur manque jamais qu’une cause pour s’y consacrer “de toute leur âme”. Reconnaissons-le, ce temps social sait entretenir chez ceux qui, momentanément, s’en étaient écartés, une nostalgie particulièrement écoeurante. Les uns sont à la merci de la première équivoque venue, les autres, orgueilleux de leur fermeté, rédigent avec un raffinement morose les codes de leurs nouvelles contraintes. Ceux-là mêmes, si peu nombreux, qui s’accommodent d’être seuls, paient leur tribut sous forme de gémissements. Ils s’ennuient, ils désespèrent ou, plus ridiculement encore, ils travaillent. Chaque bribe de ce temps, qu’ils ont si péniblement conscience de soustraire à la société, acquiert à leurs yeux une valeur extravagante. Ils s’en instituent personnellement les usuriers et, pour mieux faire fructifier leurs tristes épargnes, ils calculent, ils inventent, ils bâtissent, ils peignent, ils écrivent avec une ardeur désolée. Sans doute se livrent-ils à une sorte de transfert: ils convertissent leur temps papier en temps or, ils le consolident et l’on utilise d’instinct pour cette opération mentale un langage de finance. Il n’est question que d’un placement pour les cieux jours ou, suprême ambition de banquier philanthrope, spéculateur à long terme, d’un moyen de se perpétuer.”

“Voyez-vous,” remarqua-t-il en souriant, “je me laisse à mon tour emporter par la satire. Je stigmatise l’homme moderne, l’homme libre, celui qui, semblable aux anciens duellistes, se tient pour comblé dès qu’on lui accorde le choix des armes qui le tueront. Suivez son manège lorsqu’il hésite triomphalement entre les journaux, entre les professions, entre les églises. Entendez-le s’exprimer à son aise dans des langues qui confondent le temps et la cadence, comme l’anglais time ou l’italien tempo. Regardez-le s’éloigner avec assurance, persuadé qu’il pourrait, à son gré, ne plus revenir, alors qu’il porte en lui, plus contraignant qu’un philtre d’amour, le gage de sa soumission. Dans la forêt même où parfois il s’aventure, les fées, les sorcières, les voix anonymes sont autant d’horloges métaphoriques dont la fonction est de lui rappeler l’heure. Sous son regard, chaque surface est un cadran lisible, chaque ombre, une montre embusquée. L’agonie des minutes brame à tous les échos et, jusque dans l’emportement de son vertige, le voyageur s’écoute vieillir car c’est le temps qui bat son pouls, inexorable chef d’orchestre intérieur. Rebrousser chemin, retrouver le “temps perdu”, quelle tentation pour qui, ayant cru fuir, lui aussi, la vielle terre, reprend à son compte l’exclamation désenchantée d’un auteur connu: “Ce n’est rien, j’y suis, j’y suis toujours”.

Depuis quelques instants, mes yeux s’étaient fixés sur le troisième cadran dont l’aspect immuable commençait à me fasciner. “Que cette inertie ne vous inspire pas des images faciles de néant ou d’éternité,” me dit mon hôte d’un ton sardonique. “Dans cette horloge arrêtée, imaginez au contraire un mécanisme plus sensible que les autres, trop parfait pour enregistrer les vibrations grossières du temps social. Ailleurs, en quelque partie soigneusement occultée de ses rouages, d’imperceptibles oscillations révéleraient le passage presque impalpable du temps gratuit. Certes, la façade figée et comme morte de ce cadran est bien faite pour éloigner ceux qui reculent naturellement devant une mutation possible. Tout annonce un passage à franchir, une rupture à réaliser. Entre ce monde et l’autre, aucune transition légendaire, aucune communication discursive. On ne nous offre pas la clé d’un autre nirvana puisqu’il semble même que là où nous allons, l’extase n’ait plus de raison d’être. Nous ne renouons avec rien et peut être aurons-nous enfin brisé avec tout. Ni cérémonial, ni incantations, ni rites, mais atteindre ai point de lucidité où la notion du temps devient un fruit que l’on pèle”, et il fit avec ses doigts de petits mouvements déliés.

Je brûlais de poser une question mais, me devançant, il ajouta: “Ai-je besoin de spécifier qu’en nous retranchant du temps utile, nous entendons en aucun cas nous restreindre à la quiétude neutre du spectateur, à cette transcendance sceptique ou contemplative qui, pour ma part, me répugne absolument? Le domaine du temps gratuit est celui du risque extrême, de l’exaltation soutenue car il est à la fois le seul où l’on perde sciemment son temps, donc sa vie et le seul où tout effet dramatique, toute emphase soient inadmissibles. Le jeu lui-même s’y dépouille des compensations verbales ou passionnelles que lui avait léguées le temps social où nul acte ne se justifie sans dividende. Les anciens aristocrates prenaient la précaution de réunir tous leurs invités avant de jeter leur argenterie au fond de l’eau et les mises à mort, dans la littérature moderne, ont souvent conservé ce style tapageur. Pour nous, le gaspillage est obligatoirement non ostensible et nous chercherons surtout à donner le change. Nous ne serons ni mages, ni héros, ni justiciers, ni prophètes, mais nous aurons soin de jouer des rôles quelconques avec un faux sérieux qui pourra faire illusion. C’est à l’intérieur même du temps social et non à l’écart, ce qui déjà serait édifiant, que nous créerons, sans nécessairement le laisser entendre, des zones de refus et de légèreté.”

A cet instant, une jeune femme entra. Ce n’était pas celle que j’avais déjà vue. Elle se contenta d’incliner la tête et vint s’asseoir sur le lit sans prononcer un mot. Je me disposais à poursuivre l’entretien lorsque je m’aperçus que, manifestement, les pensées de mon interlocuteur avaient pris un autre cours.

click to enlarge

Cliquez pour agrandir

“Puis-je vous prier de ne plus revenir?” me dit-il après quelques minutes de silence. “Epargnez-moi la disgrâce de reprendre ces démonstrations orales qui ne trahissent jamais que nos propres tergiversations. Un bruit de paroles qui prétendent convaincre et il n’en faut pas davantage au temps social, momentanément conjuré, pour retrouver son arrogance.” Et me poussant aimablement vers la porte, il conclut: “La gratuité ne se sépare jamais d’un certain mutisme. Sans doute en ai-je déjà trop dit.”