This is the first chronological presentation of Marcel Duchamp´s appearance in the context of Swedish art.

This review is based on material related to Marcel Duchamp published in Sweden from 1933-1970. My sources are art magazines, literature magazines, essays, monographs, catalogues, and similar printed material in my archive: The Swedish Archive of Artists Books, Malmö, Sweden (SAAB). (See appendix.)

The reasons for this critical review are simple. First, I want to show how Duchamp was introduced in Sweden and by whom. Secondly, I aim to trace how and when his works gained public recognition, beyond the contexts of Cubism, Futurism, Dadaism, and Surrealism.

My study shows that the Swedish art world was the first to recognize this specific quality of Duchamp’s work. In Ulf Linde´s latest book Marcel Duchamp, Stockholm, 1986, page 26, he remarks: “Pontus [Hultén] was the first to interest himself in Duchamp in this country[Sweden] and, partly, he considered the exhibition [“Art in Motion,” 1961] as a tribute to Duchamp.” (1)

click images to enlarge

-

1. Ulf

Linde, Marcel Duchamp, 1986.

-

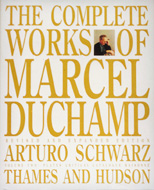

2. Arturo Schwarz,

The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp, revised and expanded edition,

1997.

I have used Arturo Schwarz´s critical catalogue raisonné of 1997, The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp, the revised and expanded edition, Thames and Hudson, 1997, as a main reference for Duchamp’s works. As far as I know, it is the latest published to date. In the following text an ‘S,’ for Schwarz, followed by the catalogue raisonné number, identifies a work by Marcel Duchamp. (2)

Notes on How Schwarz Deals with Duchamp’s Appearance in Sweden in His Index and Bibliography of 1969 and 1997.

It is obvious that Schwarz has not understood the importance of the Swedish art context in connection with Duchamp’s kinetic works and readymades.

In Schwarz´s index, pages 619-630, from 1969, the following entries refer to Swedish art figures: Ilmar Laaban, Ingemar Gustafson (Leckius) and Erik Lindgren on page 592, (seeSalamander below), while Pontus Hultén has three entries on pages 482, 496, and 600. The Moderna Museet, (Stockholm), has sixteen entries, but they all refer to the replicas of Duchamp’s readymades made by Linde and Hultén during 1960-1963. Though Ulf Linde has as many as twenty-six entries, there are no remarks about how important his involvement must have been to the general acceptance of Duchamp and his readymades.

Hultén’s three entries in Schwarz’s index, 1969, mention the replica of the “Rotary Glass Plates (Precision Optics),” 1920, S 379 a, and the replica of “Door: 11 rue Larrey, 1927,” S 426, both made in 1961. The last entry refers to the “Bicycle Wheel.” Of Ulf Linde’s twenty-six entries, ten refer to his participation in Schwarz´s book Marcel Duchamp ReadyMades,1913-1964, Milan, 1964 (3). Twelve entries refer to Linde’s readymade replicas, one to Linde’s Swedish translation of “The Green Box” in Konstrevy,1961-1963, (see entry), one to his book Marcel Duchamp, 1963, and three to his interviews.

click images to enlarge

-

3. Walter Hopps, Ulf Linde, Arturo

Schwarz, Marcel Duchamp, Readymades,

etc. (1913-1964), 1964

-

4. K. G. Hultén (Pontus

Hultén ed.), Rörelse i konsten,

Bewogen Beweging, 1961.

The three Swedish poets Ilmar Laaban, Erik Lindegren, and Ingemar Gustafson (Leckius) are in the index for their Swedish translation of SUR cen SUR and Breton’s Lighthouse of the Bride in Salamander, no. 1, 1955, (see entry).

Under Section XX, “Bibliography of Works Quoted,” 1969, only Ulf Linde’s MARiée CELibataire is noted from Schwarz´s Marcel Duchamp: Readymades, Etc., 1964.

In Schwarz’s 1997 edition, Pontus Hultén’s index is not mentioned at all, which is strange. His name does, however, appear in Section XXII, on page 910 [Under the “Bicycle Wheel”] for the catalogue “Bewogen Beweging” (“Art in Motion,” 1961, Amsterdam), which is the same note cited as no. 144, page 600, in the 1969 edition. (4)

Yet, these entries are incorrect. What Schwarz refers to might be K. G. (Pontus) Hulten’s text A Short Survey about the History of Kinetic Art During the 20th Century, published in the catalogue of “Art in Motion.” Schwarz also forgets to mention that this exhibition was curated for the Moderna Museet and that Hultén, along with Carlo Derkert, Daniel Spoerri and Billy Klüver, was a member of the exhibition committee. Pontus Hultén was actually the editor of the catalogue. It is clear that he was in fact the one who initiated “Art in Motion.” (See above quote from Linde’s book,1986). In addition, Schwarz only mentions the Amsterdam venue. The reasons for Schwarz’s oversight in this area, specifically in Hultén’s involvement, are unclear. Even Linde has no more than seven entries in the 1997 edition. These include no. 169, no. 175, and no. 195, which are all interviews with Duchamp. The other four entries refer to Linde’s translation of the “Green Box” and his participation in Arturo Schwarz´s book Marcel Duchamp: Readymades Etc., 1964.

Under Schwarz´s “Bibliography of Works Quoted,” Section XXIII, 1997, is Hultén, Karl Gunnar Pontus, The Machine, 1968, and Marcel Duchamp, Work and Life, 1993. Only Ulf Linde’s book Marcel Duchamp, 1963, and his contribution, MARiée CELibatairein in Schwarz´s Marcel Duchamp: Readymades Etc., 1964, are mentioned here.

In Schwarz´s 1997 edition, Section XXIV, Timothy Shipe’s “Bibliography 1969-95,” acts as a supplement to the descriptive bibliography for the 1969 and 1970 editions. Here, Linde’s two books of 1963 and 1986 are mentioned. Additionally, he has three entries under Section 4, within the bibliography, “Secondary Literature: Articles and Essays”. Two of them appear in the catalogue that was published for Duchamp’s retrospective exhibition at the Centre Georges Pompidou in 1977. Under Section 5 of Shipe’s bibliography, “Exhibition Catalogues,” Linde appears again, now as the editor for the catalogue published by the Moderna Museet, 1986-1987, for the exhibition “Marcel Duchamp.” Pontus Hultén is now mentioned as the editor of the catalogue published by Palazzo Grassi, Venice, 1993.

Section XXV, “Exhibition History,” of the 1997 edition, is organized in two parts. The first part documents solo exhibitions from 1937. The second part records group shows in which Duchamp participated during his lifetime. This last section is highly selective according to Timothy Shipe. The following solo exhibitions in Sweden are recorded: “Marcel Duchamp,“Bokkonsum, 1960, “Marcel Duchamp,” Galerie Burén af Eva, 1963, and “Marcel Duchamp,” Moderna Museet, 1986-1987. The group exhibitions are “Art in Motion,” 1961, and “Dada,” Moderna Museet, 1966. These are all listed, but Pontus Hultén’s exhibitions “Art in Motion” and “Bewogen Beweging” are the only major references. The fact this was ignored remains somewhat perplexing.

Though Schwarz has mentioned those who were interested in Duchamp’s works in Sweden, he has excluded essential information and conclusions concerning Duchamp’s early appearance in the context of Swedish art. Thus ignoring its effect on his career since the mid-fifties in regard to his kinetic works and readymades.

Comments on Lebel’s Index

Robert Lebel’s first monograph from 1959, (5) was published five years after the exhibition at Samlaren in collaboration with Duchamp. Curiously enough, that show and the magazine,KASARK [no. 1], are not listed. In Lebel’s bibliography, under “General References,” no. 98, is the Hultén (K) & Vasarely (V) catalogue Le Mouvement, Galerie Denis René, Paris, 1955. Under “Special Studies and Documents,” no. 68, is Bo Lindwall’s article Saboteur et anti-artiste, from Konstrevy,1955 (see entry).

In Lebel’s revised edition of 1967, (6) Ulf Linde’s book, Marcel Duchamp, 1963, appears under the “Bibliography: Addenda, Part 3” no. 93. In part 5 of the “Addenda,” under no.103, is “Bokkonsum, Invitation Card,” with a foreword by K. G. Hultén, Stockholm, 1960. No.108 lists “Art in Motion,” Amsterdam, Stockholm, and Copenhagen.

Lebel writes in “Catalogue Raisonné: Addenda, Part 2,” 1967, “Until 1960, Duchamp had usually made or chosen himself the replicas and editions of his own works. In 1960, a group of his Scandinavian admirers, including K. G. Hultén, Director of the Stockholm Moderna Museet, Ulf Linde, P. O. Ultvedt and Magnus Wibom, started working together on replicas which were later approved and signed by Duchamp.” Though Lebel’s comments are correct, he, like Schwarz, does not see the crucial importance of Duchamp’s early appearance in Sweden in regard to his kinetic works and readymades.

click images to enlarge

-

5. Robert Lebel, Marcel

Duchamp, 1959.

-

6. Robert Lebel, Marcel

Duchamp, 1967.

click to enlarge

![KASARK

[no. 1]](/issues/issue_3/Articles/Eriksson/./07.jpg)

7. KASARK

[no. 1], 1954, Galerie Samlaren.

The following compilation delineates how and when Marcel Duchamp was introduced within the context of Swedish art. It was quite early, beginning in 1933. At this point, most of the early articles discuss Duchamp within the realms of Cubism, Futurism, Dadaism, and Surrealism.

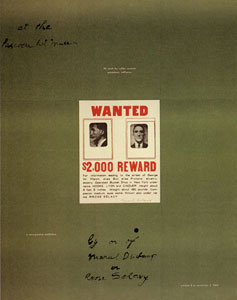

Pontus Hultén was the first to acknowledge Duchamp’s crucial works of kinetic art and readymades. The first time he did so was in the inaugural issue of KASARK, 1954 (Published by Galerie Samlaren, Stockholm) (7), and continued to do so in the following three issues. These articles became a platform for Hultén’s concepts and extensive knowledge of Duchamp’s kinetic art and readymades. KASARK is one of the rarest art magazines published in Sweden, (see following entry), and can be compared with The Blind Man. (The name KASARK originates from Mark Twain´s short story The Ascension of Captain Stormfield. It is defined as a unit of weight. One kasark equals the weight of one million earths.)

Readymades at Galerie Eva af Burén, Stockholm, 1963

The exhibition, including Linde’s replicas of Duchamp’s readymades at Galerie Eva af Burén, Stockholm,1963, was the first show to ever concentrate on his readymades. Duchamp was quite enthusiastic about the proposal. He wrote back, “For the show at Mrs. Buren’s I agree thoroughly with your idea to have every Readymade shown in exact replicas, Marcel,” and thought that Schwarz should use Linde’s replicas as models for the 1964 editions of the readymades. (Ulf Linde’s Marcel Duchamp, 1986, pages 52, 57). Concerning the release of the replicas in 1964 in Milan, Schwarz borrowed Linde’s copies for the show. It was there that Duchamp signed Linde’s versions, which are now at the Moderna Museet, Stockholm.

Crucial Exhibitions in Sweden

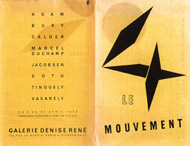

My study attempts to shows how important the Swedish art world must have been to the overall appreciation of Duchamp’s kinetic works and readymades. When looking at the record of exhibitions related to Marcel Duchamp since the 1950s, one consistently finds the involvement of Pontus Hultén. It began in 1954 with the exhibition “Objects or Artefacts Reality Fulfilled“ at Agnes Widlund’s Galerie Samlaren, February – March, Stockholm, 1954, and continued with “Le Mouvement,” at the Galerie Denise René, Paris, 1955, (8). The exhibitions “Marcel Duchamp,” Bokkonsum, Stockholm, 1960, (9) “Art in Motion,” Amsterdam, Stockholm, Louisiana, Denmark, 1961, and “The Machine,” the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1968-1969 (10), followed. Some of these exhibitions are listed in Lebel’s and Schwarz’s texts, but both failed to acknowledge their importance.

In 1960 Ulf Linde published Spejare (11) that had an enormous impact on Sweden’s art world, primarily due to his presentation of Marcel Duchamp’s works. Yet even Linde forgot to mention Galerie Samlaren and KASARK in his text and made a significant mistake about the “Bottlerack” by saying “1914 [Duchamp] took a bottlerack from a cafe and exhibited it at a salon as a sculpture,” page 43. This, as I explain later, is an incorrect statement. (see entry).

click images to enlarge

-

8. Le Mouvemenet,

Galerie Denise René,

Paris, 1955. .

-

9. Bokkonsum, announcement

card, 1960.

click images to enlarge

-

10. The Machine, Museum

of Modern Art 1968-1969.

-

11. Ulf Linde, Spejare,

1960.

Duchamp’s Intriguing Titles

It is well known that Duchamp was very specific about his titles. Therefore, I have chosen to quote the titles from Arturo Schwarz’s latest catalogue raisonné for three reasons. First, it is the most complete list of Duchamp’s works, like Köchel’s register of Mozart’s works. Second, it is based on Schwarz’s direct collaboration with Duchamp, as was the previous catalogue raisonné of 1969, revised and updated in 1970 and 1997. Third, Schwarz has a cross-reference to Robert Lebel’s catalogue raisonné, the first Duchamp monograph published in 1959 and later revised in 1967.

Duchamp’s titles have probably been altered or misunderstood through the years. I have therefore quoted the titles as they stand in the captions of the Swedish material, and place parentheses around the titles as they appear in Schwarz´s latest catalogue raisonné.

Common Errors Made Concerning Duchamp’s Readymades

In my study, I examine some of the misunderstandings of Duchamp’s works that are commonly made by art critics and readers. For example, it is often said that his readymades have been exhibited in their original versions. This is untrue, as they have obviously been copies or replicas. He specifically confirmed new replicas of lost readymades made by Ulf Linde, Richard Hamilton and others. Additionally, there are the Schwarz editions from 1964 that celebrate the fiftieth Anniversary of the readymades’ introduction in the art world. I do not think Duchamp had any objections about that, because it coincides with his attitudes towards art and the art world. His opinion about art and artists can be examplified in his response to the question “Who is a famous artist?” to which he answered: “He’s a lucky guy.” (Interview with Ulf Linde, Stockholm, 1961.)

(For a closer look at Duchamp’s readymades refer to Hector Obalk’s essay The Unfindable Readymades in ToutFaitJournal, Vol. 1, Issue 2, 1999.)

Due to all the errors concerning the provenance of Duchamp’s works, particularly his readymades, I have listed them in an appendix. If a work exists, it is listed along with its current location. The appendix also includes Schwarz’s inclusive categories of each item.

In the appendix, I have also listed my primary sources chronologically and indicated further readings regarding people of interest.

Marcel Duchamp in Sweden 1933-1970

1933

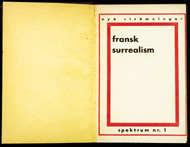

Nya Strömningar, Fransk Surrealism, Spektrums Förlag, 1933

Marcel Duchamp first appears in a Swedish publication in Nya Strömningar, Fransk Surrealism, published by Spektrum Press in 1933. Gunnar Ekelöf, the Swedish poet, wrote the introduction and was responsible for translating this anthology of French surrealist poems. (12) (13)

click images to enlarge

-

12. nya strömningar,

spektrum förlag, 1933.

-

13. Marcel Duchamp, surealistiskt

föremål, illustration in “nya strömningar 1933”.

Marcel Duchamp appears twice in this book. He is first mentioned in a note on page 47. That note refers to a critique about the film history written by Salvador Dali where he comments on René Clair’s film Entr´Acte. “Despite René Clair, it really resumes the concepts of Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray and Francis Picabia…”

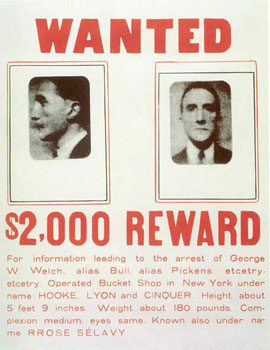

Duchamp’s second appearance is in conjunction with Benjamin Péret’s poem För Att Fördriva Tiden, (While Away the Time), page 53. The poem is illustrated with one of Duchamp’s kinetic works, a very advanced choice of illustration at the time. The Swedish caption reads “Marcel Duchamp, surrealistiskt föremål” followed by the pun in French“rose selavy et moi, nous estimons les ecchymoses des esquimaux aux mots exquis.” The correct title is actually “Rotary Demisphere (Precision Optics),” 1925, Paris, S 409. The piece was exhibited in Stockholm in 1961 at “Rörelse i konsten” (“Art in Motion”). According to Schwarz, “Precision Optics” has been in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York, since 1970.

1934

BLM, Bonniers Litterära Magasin, Volume 3, no. 3, 1934

In Bonniers Litterära Magasin, 1934, (14) Gunnar Ekelöf published his article Från Dadaism till Surrealism. He introduced Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia, and Andre Breton on page 36, where he wrote: “A major contribution to the continuing development of the movement [Dada] became the figures who transported it to Paris. They consisted of Francis Picabia and Marcel Duchamp, both astounding word jugglers experimenting with artistic values, and a group of young writers centered around the magazine ‘Literature’ published by Andre Breton.”

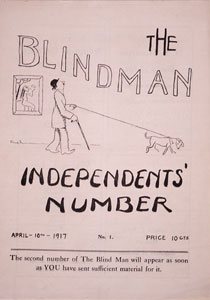

Ekelöf also mentions that Duchamp and Picabia had access to the following magazines: Duchamp’s Wrong-Wrong, ( Rongwrong, 1917), S 348, The Blind Man, (The Blind Man No. 1: Independents´ Number, 1917), S 346, The Blind Man No. 2: P.B.T., 1917, S 347 and Picabia’s 291, 1915, and 391, 1920.

Ekelöf even points out that “[‘Fountain,’ (1917, S 345)] … which under the pseudonym R. Mutt was sent into the Independents Show in New York, originated from someone in the circle. Since the Fountain simply was a urinal, it was therefore rejected.”

click images to enlarge

-

14. BLM, no. 3

1934. Gunnar Ekelöf, “Från dadaism till surrealism”

-

15. konkretion,

no. 5-6 double-issue 1936.

1936

Konkretion, no. 5-6, 1936

Two years later, Duchamp appears in Vilh. Bjerke-Petersen’s magazine Konkretion, no. 5-6, 1936, published in Copenhagen, Oslo and Stockholm. This magazine is written mainly in Danish. (15)

This is the final and special double-issue about “Surrealism in Paris”. Duchamp’s contributed an illustration for the Belgian poet, Gisèle Prassino’s text Den forfuulgte unge pige, (The Pursued Young Girl) 1935. The caption reads, “Marcel Duchamp: ‘Moustiques domestiques demistock’. Photo Man Ray.” In Schwarz, the title of the work is “Monte Carlo Bond,” Paris, 1924, S 406, and called an “Imitated Rectified Readymade.” Duchamp made less then eight of the planned 30 copies of version a. of the “Monte Carlo Bond.” Version b. of the work was done in 1938, and a version c. in 1941.

1948

Prisma, no. 1, 1948

Duchamp appears in a Swedish text twelve years later in the inaugural issue of the exclusive magazine Prisma, no. 1, 1948.(16) He is mentioned in the section called “Experimentalfältet (The Field of Experiments),” page 99, where Ebbe Neergaard writes about “French-American-German experimental film” in New York, specifically the film “Dreams That Money Can Buy.” The film consists of six parts compiled by Hans Richter and includes works by contributing artists Fernand Léger, Max Ernst, Man Ray, Alexander Calder, and Marcel Duchamp. The article is illustrated with five photographs, one of which is illustration no. 5, a detail from Duchamp’s scandalous painting, “Nude Descending a Staircase,” S 342.

This film was also shown on May 21, 1958 at the Moderna Museet’s film studio during “Apropå Eggeling, Avant-Garde-Film.” (17)

click images to enlarge

-

16. Prisma,

no. 1 1948.

-

17. Apropå Eggeling,

Avantgarde Film Festival, catalogue, 1958.

1948

Konstrevy, no 3, 1948

In Konstrevy, no. 3, 1948, Haavard Rostrup writes about Marcel Duchamp’s brother Jacques Villon (18). Rostrup refers to Marcel in the following passage: “Jacques Villon’s name is really Gaston Duchamp and brother to the cubist sculptor Raymond Duchamp-Villon, who died in 1918, and to the painter Marcel Duchamp. First a cubist painter and later one of the founders of Dadaism, but since 1920, turned his back on art and devoted himself to chess.”

click images to enlarge

-

18. Konstrevy,

no. 3 1948.

-

19. Konstrevy,

no. 4-5 1950.

1950

Konstrevy, no 4-5, 1950

Konstrevy’s double issue, no. 4-5, 1950, features Gabrielle Buffet-Picabia’s article “Några minnen från den abstrakta konstens första år” (Some Memories From the First Years of Abstract Art). (19)

She writes: “In 1910 I became acquainted with the brothers Duchamps the oldest Raymond Duchamps, and the nowadays the widely appreciated, completely personal painter, Jacques Villon. [Both were] careful spectators to the fast development of painting. But the youngest, Marcel Duchamp, already showed distinctive qualifications to be as controversial as he was: one of the strangest spirits of his time and the deepest influence on abstract art. Marcel Duchamp was among the young circle that was eager to fight. With his work, consisting of a few paintings, his opinions and way of living, [he] had his own intuition and intelligence. Yet without effort and affection, [Marcel Duchamp] reached beyond the systematic destruction of the traditional standards of art, which up until now were reverentially accepted theories. Thus he appears as one of the predecessors of surrealism; but the peak of the anarchism was first achieved in 1915. When we first met Duchamp, he was sincerely engaged with an issue that was developed by Italian Futurism i.e. the possibility to express movement within the frame of static painting. One of his earliest and most well known canvases ‘Nu Descendant au Escalier’ shows an almost cinematographic decomposition of movement within the context of a skeleton. Duchamp’s acquaintance with Picabia was of great importance to both of them.”

Further on she writes: “In 1910, at rue Trouchet was an exhibition with Picasso, Duchamp and Picabia, already showing paintings with a striking boldness, but still far from the character they later achieved.”

Her article continues on about the Salon d’Independent, 1912, where she writes: “That same year there was the great exposition ‘La Section d’Or’ with works by, Duchamp, Gris, Delaunay and Picabia. Finally in January 1913 in New York there was a large audience of genuine American characters invited to a giant exhibition in order to educate them in the abstract art. I attended the opening, en elaborate, elegant affair. I remember that a man in a white tie opened the ceremonies. On a rostrum he explained: ‘Ladies and gentlemen, this exhibition that covers such an expanse of wall space, consists of so many canvases and has cost us such a considerable expense to arrange is presented before you. It is now your task to learn and to understand modern art, and that’s that.’ Without finding any understanding the new art had conquered its place in the intellectual life, but also in another field: The Speculation. Since that time it has tried and often succeeded to even involve art into its unceasing and humiliating race, similar to that of the value of stocks.”

Three works of Duchamp and Picabia illustrate the article. Included is Marcel Duchamp’s”Why Not Sneeze Rose Sélavy?” 1921, (Photo: R. Sélavy, a Semi-Readymade, New York 1921, S 391). According to Schwarz, the original is at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. A replica by Ulf Linde made in 1963, for Duchamp’s exhibition at the Galerie Eva af Burén, is now at the Moderna Museet (MMS), which was signed and dated by Duchamp in Milan in 1964.

In reference to Duchamp’s “Elevage de poussière,” Photo: Man Ray 1920, (“Bred Readymade [DustBreeding],” S 382),Schwarz writes that both Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp took this photograph. It currently belongs to the Jedermann Collection, N.A.

Marcel Duchamp’s “Nu Descendant un Escalier,” 1912, (“Nude Descending a Staircase No. 2,” S 242), now resides at the Philadelphia Museum of Art along with Duchamp’s first version, S 239.

The chief editor of Konstrevy in 1950 was Mrs. Ingrid Rydbeck-Zuhr. Choosing Duchamp’s pieces as illustrations was an advanced and visionary decision for 1950, as those works were somewhat controversial at the time.

1951

Konstperspektiv, 4, 1951

In issue no. 4, 1951, Gunnar Hellman writes an article Variationer på ett gammalt tema(Variations on an Old Theme), where he quotes Oscar Reutersvärd’s catalogue text from the exhibition “Neo-Plastic Art” at the Galerie Samlaren, Stockholm, 1951. Hellman’s article is illustrated with Duchamp’s “Nu Descendant un Escalier,” 1912, (“Nude Descending a Staircase No. 2,” S 242), with the following caption, “In 1912 the Frenchman Marcel Duchamp did this nude model, descending a staircase.” Hellman’s reason for using Duchamp’s painting as an illustration remains unclear, for according to the catalogue; it was never actually shown at the exhibition. (20)

click images to enlarge

-

20. Konstperspektiv,

no. 4 1951.

-

21. Konstrevy,

no. 2 1952.

1952

Konstrevy no 2

In Konstrevy no. 2, 1952, Gabrielle Buffet-Picabia submitted the article I dadaismens tid (In the time of Dadaism) where she discusses Duchamp’s stay in New York. (21)

“Dadaism existed before it got a name,” she writes.

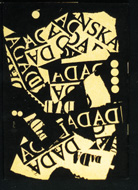

Gabrielle describes her ten-year experience of the Dada-epoch and divides it into three parts. She names the first Dada-epoch in New York, Pré-Dada. The second, the real Dada-epoch, she writes, took place in Zurich while the third Dada-period was in Paris.

She continues to describe Dadaism in Germany with Max Ernst and Hans Richter in Düsseldorf, Huelsenbeck in Berlin, and with Schwitters in Cologne. The latter, the author characterizes as the complete Dadaist, from the very language he used to his specifically arranged home and lifestyle. Laconically, she states that Dada was born in 1917.

Buffet-Picabia tells the story about the conception of Dada, which many Dadaists have claimed to coin. She explains that it can be traced to a minor accident. The Larousse dictionary happened to open onto the page where the word “Dada” was listed, as Hugo Ball and Hulsenbeck were looking for a sensational name for a dance sketch. A sketch in which Emmy Hennings, Hugo Ball’s wife, would perform at Cabaret Voltaire.

She writes, “Picabia and Duchamp, the first newsmakers of the period that tore [the year] 1910 from all bonds with classicism and the four Gospels. Though they were each other’s opponents, both in reactions and methods, there was a strange competition to reach destructive and paradoxical, blasphemously and inhuman suggestions. Guillaume Apollinaire often took part in these attempts of demoralization, which were also attacks of witticism, puns, and jokes, and even replaced the formal values of beauty with personal dynamism and suggestive, inventive and individual forces. This playful search into the unknown dimensions and into the unexplored regions of being, this spirit of invention, which has never come back, it seems to me, contained all the seeds, which later became Dadaism, and even that, has since then grown on to new ramifications.”

She continues, “For his personal use Duchamp came to create a mechanical world of fantasy, consequence and logic, applied to a sentimental gearwheel deed, specifying one necessary text in order to understand the painting as ‘la Marié Mise à nu par ses Célibataires Mêmes´.” (S 404)

And further,

“In this art environment Duchamp received a popularity, which he got due to the lasting success of his first exhibited work in the United States: ‘Nu Descendant un Escalier’. Between two whiskies and two puns he demonstrates an attitude of distance from everything, even from himself; his lacking interest in human standards is not the least of reasons that he is subject to a pleasant curiosity in the admiring milieu. Soon he declares that he is going to end all artistic production and keeps his word. If he still takes part in any artistic manifestations, he does it in order to create a scandal. For example, he shows, at the New York Independents Show, one Ready-made called ‘Fountain,’ which is nothing else but a urinal. Later, not the least, sensational scandal, he puts a moustache on the Mona Lisa, symbolizing his contempt for the fetishism of art…”

“…It is during this period when Cravan, boxer, poet and, since 1912, publisher of a small avant-garde magazine ‘Maintenant,’ made his notorious lecture. Cravan was asked to give an enlightening lecture for a select party. He was drunk and insulted, in obscene terms, his audience of elegant ladies and started calmly to undress until two policemen took him away with handcuffs. He was immediately released by Arensberg’s intervention and was enthusiastically congratulated by his friends Picabia and Duchamp, who were actually responsible for the scandal.”

This article is illustrated with works by Picabia, Duchamp, Jean Arp, Sophie Tæuber Arp, and Kurt Schwitters.

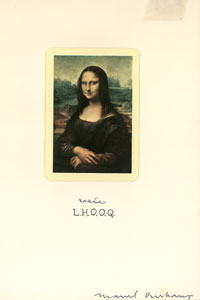

Marcel Duchamp’s contribution to the article is the infamous “La Joconde.” The correct title is L.H.O.O.Q. according to S 369, and is a “Rectified Readymade” made in Paris in 1919. The original currently belongs to a private collector in Paris. In regard to this major work, Schwarz describes five replicas, one of which was made in an edition of 38 numbered copies. The first 35 are signed and three remain unnumbered.

An ambiguity remains with this work, as with so many of Duchamp’s pieces. It is unclear as to which works, particularly which readymades, were exhibited as originals.

(In my own essay in

Konstmagasinet, no. 14, 1991, (22) I have listed Duchamp’s readymades that still exist in their original versions. His “Bottle Dryer [Bottlerack],” S 306, is perhaps the best example of uncertainty concerning the provenance of Duchamp’s Readymades. See

index below.) Picabia’s “La Joconde” raises such as issue. He originally intended to use Duchamp’s work as a cover illustration for the magazine

391, but Duchamp’s piece did not arrive in time. Therefore Picabia resorted to making his own version without the goat’s beard, which Duchamp later corrected.

click to enlarge

22.

Konstmagasinet, no. 14 Nov. 1991, Leif Eriksson, “Marcel Duchamps

Readymades: Original och kopior!”

The Bottle Dryer [Bottlerack]

Inconsistencies arise when discussing Duchamp’s most famous ready-made, “Bottle Dryer [Bottlerack].” Even one of the best exegetes of Duchamp’s works, Ulf Linde, erred in his book Spejare, where he wrote: “In 1914 he fetched a Bottle Dryer [Bottlerack] from a cafe and exhibited it at a salon as a sculpture.” Considering that Linde’s book was the first penetrating analyses of Duchamp’s works in Sweden, it had an unfortunate impact, for that inaccurate description still remains. The original version has actually never been exhibited, like so many of Duchamp’s readymades.(23)

I think that Duchamp did not care if it was an “original” or a “replica” that he exhibited. His comment on various interpretations or replicas of his works was “It amuses me.” This remains congruent with his attitude towards art and the art world, against which he protested through the act of choosing the readymades.

click images to enlarge

-

23. Leif Eriksson. Some versions

of Bottlerack 1914-, 1987.

-

24. Francis M. Naumann

& Hector Obalk, Affectt._ Marcel The Selected Correspondence

of Marcel Duchamp, Thames & Hudson 2000.

The original version of “Bottle Dryer [Bottlerack]” is lost. Duchamp bought his first one at Bazaar de l’ Hotel de Ville in Paris, 1914. The disappearance of the original version is due to his sister, Suzanne, whom Duchamp had asked to clean his apartment in Paris while he was away in New York. She simply cleaned it away.

In a new book (24) Affectt Marcel, The Selected Correspondence of Marcel Duchamp by Francis M. Naumann & Hector Obalk, (Thames & Hudson, 2000), there are two letters written in January and October of 1916 to Suzanne Duchamp where Marcel introduces his concept of the ready-made. “Now, if you have been up to my place, you will have seen, in the studio, a bicycle wheel and a bottle rack. I bought this as a readymade sculpture. And I have a plan concerning this so-called bottle-rack. Listen to this: here in N. Y., I have bought various objects in the same taste and I treat them as ‘readymades’. You know enough English to understand the meaning of ‘ready-made’ that I give these objects. I sign them and I think of an inscription for them in English. I´ll give you a few examples. I have, for example, a large snow shovel on which I have inscribed at the bottom: In advance of the broken arm, French translation: En avance du bras cassé. Don’t tear your hair out of trying to understand this in the Romantic or Impressionist or Cubist sense-it has nothing to do with all that. Another ‘readymade’ is called: Emergency in favour of twice, possible French translation: Danger /Crise/ en faveur de 2 fois. This long preamble just to say: take this bottle rack for yourself. I’m making it a ‘readymade,’ remotely. You are to inscribe it at the bottom and on the inside of the bottom circle, in small letters painted with a brush in oil, silver white colour, with an inscription which I will give you herewith, and then sign it, in the same handwriting, as follows: [after, Marcel Duchamp (end of letter could very well be missing)]”

In the letter dated October 16, 1916, he returns to the same subject and asks, “Did you write the inscription on the ready-made? Do it. And send it, [the inscription], to me and let me know exactly what you did.”

Later Duchamp, in his text Apropos of Readymades, 1961, describes how the term Readymade arose. “In 1913 I got the good idea to attach a bicycle wheel to kitchen chair and saw it turn.” In New York in 1915 he bought a snow shovel and wrote on it: In advance of the Broken Arm. “It was about this time the word readymade come to my mind to describe this form of appearance.”

Duchamp bought the second version of “Bottle Dryer [Bottlerack]” for his sister in 1921. The work was signed by Duchamp: “Marcel Duchamp/Antique certifie,” S 306 a., and was reproduced in Lucy R. Lippard’s essay in the MoMA’s Duchamp catalogue in 1973. This version belonged to the collection of Robert Lebel, and is currently in the collection of his son, Jean-Jacques Lebel, in Paris.

Duchamp produced his third version of “Bottle Dryer [Bottlerack]” in 1936. It was exhibited the same year at Charles Ratton’s gallery in Paris, May, 1936. This third copy belonged to Man Ray, but there is no record of its current location. Yet it appears in the photograph showing the interior of Ratton’s gallery, reproduced in the catalogue “Dada and Surrealism Reviewed,” London, 1978. Robert Rauschenberg bought a “Bottle Dryer [Bottlerack]” in which Duchamp signed the following, “Impossible de me rappler la phase original/Marcel Duchamp/1960.” This third version was exhibited at the Pasadena Art Museum, 1963, in Duchamp’s first retrospective exhibition.

In 1961, Duchamp selected a “Bottle Dryer [Bottlerack]” for his wife Alexina Duchamp, (She was deceased in 1995), with the inscription, “Marcel Duchamp 1914,” (Replique, 1961).

In 1963, Ulf Linde made a “Bottle Dryer [Bottlerack],” now at the Moderna Museet. This version was exhibited at the Schwarz Gallery, coinciding with the release of the edition of replicas made by the gallery in Milan, 1964, in order to celebrate the 50th Anniversary of Duchamp’s first Readymade. Schwarz released an edition of eight signed copies. Two copies outside the edition were reserved for the artist and Schwarz and are inscribed, “ex Rrose and ex Arturo.” Another two copies were produced for exhibition purposes and contain the following inscription, “Ex. h.c. pour exposition, 1964” and “Ex I/II donated to Israel Museum, Jerusalem, on the occasion of a Duchamp retrospective, 1972,” S 306.

There are also other versions, specifically one, which Daniel Spoerri lent to Bokkonsum’s exhibition in 1960. This version is not mentioned in Schwarz, perhaps because Duchamp never signed it. One of the most recent “Bottlerack” I have seen was shown in the exhibition “A House is Not a Home” at Rooseum in Malmö, October 18 – December 14, 1997.

When I asked the museum director, Bo Nilsson, where he had found the “Bottle Dryer [Bottlerack],” he told me that he and the former director, Lars Nittve, had some serious problems finding a copy. “You could have called me,” I answered, sensing a distinct note of irritation.

My own copy of the “Bottle Dryer [Bottlerack]” was purchased by my friend Torsten Ridell in the late 1970’s at Bazaar de l’ Hotel de Ville. My version is a meta piece, a re-made, which brings it back to its original purpose, i.e. to dry wine bottles.

In 1997, I ordered a new bottlerack made of plastic by my friend Jean Luc Guinnement in Paris, but he misunderstood my request and sent me a green painted metal copy also purchased at Bazaar de l’ Hotel de Ville in Paris. Following this mistaken delivery, Angelica Juhlner in Fox Amphoux, succeeded in finding the plastic variant in Bajoule, Provence. This copy has a bright yellow bottom plate and a blue rack, which can be dislocated into smaller parts. This version is included in my own project “Pole Room,” 1977, where all the items allude to the fact that blue and yellow become green when mixed. This plastic version has an amusing connection to the description of what Elvis Presley was wearing when he was found dead in his bathroom: “He died in his pajamas, blue top and yellow bottom.”

Duchamp’s “Bottle Dryer [Bottlerack]” shows indeed that “Ars longa vita brevis…” to use a common incomplete quotation.

Duchamp’s “Bottle Dryer [Bottlerack]” was exhibited at MoMA’s “Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism,” 1936-37. This is not entirely the case, for that “Bottle Dryer [Bottlerack]” was actually Man Ray’s photograph of a “Bottle Dryer [Bottlerack],” probably the copy, which was exhibited by Charles Ratton in May, 1936. The MoMA’s catalogue pictures a reproduction, in which the “Bottle Dryer [Bottlerack]” stands on a corner of a table. That catalogue does contain the proper origin, but that information is lost in later catalogues and books. (25)

25. Duchamp:

“Ready-made,” 1914. Photo Man Ray.

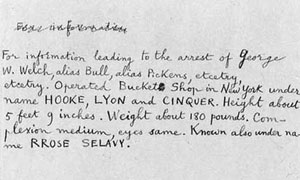

KASARK is a seven-page magazine, (26), published by Galerie Samlaren in February, 1954. Galerie Samlaren was one of the most important galleries in Stockholm from 1943 to 1977. During the 1950s, Pontus Hulten and Oscar Reutersvard and Hans Nordenstrom were the curators and editors of Kasark. On page 6, K. G. H. (Pontus Hultén) wrote an article with the headline “READY-MADE.” This is the first time someone in Sweden attempts to explain what Duchamp’s readymades represent. The following two works by Marcel Duchamp are reproduced in this issue of KASARK. (sic)

Marcel Duchamp: “Ögat i Biljardbollen,” 1935, Rotorelief för grammofon. Bilden roterar med lägsta hastighet och betraktas med ett öga, (The eye in the billiard ball, 1935. Rotorelief for gramophone. The image will rotate at the slowest speed and looked at with one eye), “Rotoreliefs (Optical Disks),” 1935, S 441. First edition, 500 sets, each set with 6 cardboard disks printed on both sides. About 300 sets were lost during World War II.

Marcel Duchamp: “Flasktorkare, Ready made,” 1914. (Bottle Dryer [Bottlerack]), Ready-made, 1914, S 306.

click images to enlarge

-

26. KASARK [no 1 1954]. K. G. H.

(Pontus Hultén) READY-MADE.

-

27. Catalogue Galerie

Samlaren, Stockholm 1954.

1954

Konstrevy, no. 3

On page 131, Ulf Linde reviews the exhibition “Object or Artefacts Reality Fulfilled” at the Galerie Samlaren in Stockholm, 1954 (27). He mentions Dada and makes a specific comment on a piece bought at EPA, a one price store company in Sweden, similar to Bazaar de l’ Hotel de Ville in Paris, that sold a variety of inexpensive goods. His comment refers to a piece no. 33 in the exhibition catalogue by V. Enhult, (an anagram and pseudonym for Pontus Hultén, an organizer of the exhibition), with the title “Object with unknown application, ready-made found at One Price Store EPA in Stockholm, 1952.” Linde writes,“The title must be understood as an attempt to release the object from all trivial relations to flour bags in order to make it an aesthetic object of ‘exclusive uselessness.'” He does not write anything about Duchamp.

1954

Odyssé, no. 2 -3

In this issue there is a note about Picabia, mentioning that Duchamp published Dadaist publications 291 and 391.

1954

Odyssé, no. 4

Dag Wedholm published Odyssé. The other editors included Ilmar Laaban, Öyvind Fahlström, Gösta Kriland, Pär Wistrand, and V. Lundström. (28) (29)

click images to enlarge

-

28. Odyssé no.

4, 1954, cover

-

29. Odyssé no.

4, 1954, “Marcel Duchamp”.

Gösta Kriland, artist, and Ilmar Laaban, poet, have translated fourteen of Marcel Duchamp’s notes. There is also a biographical note about Duchamp, which points out that he is one of the leading Dadaists, who published a number of magazines together with Picabia and others. “[He has used the pseudonym] L.H.O.O.Q. – Elle a chaud au cul. Book: Rrose Sélavy. Film: Anemic Cinema. After 1920 [Duchamp] only temporarily devoted himself to art – but more to chess.” (L.H.O.O.Q., S 369.)

1954

Gåsblandaren, hösten, 1954

Students at the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm have published Gåsblandaren and Vårblandaren (Goose Blender and Spring Blender) since 1863. Among the editors during 1951-1955 was Hans Nordenström, one of Pontus Hultén’s closest friends, who participated in many of Hulten’s early projects in the 1950s and 1960s. On the front cover is a collage of Gåsblandaren, autumn, 1954, where you can find one of Duchamp’s Rotoreliefs, S 441. (See item no. 2 in “Das gedruckte Museum von Hulten,” 1996.) (30)(31)

click images to enlarge

-

30. Gåsblandaren,

autumn 1954.

-

31. Lutz Jahre,

Das gedruckte Museum von Pontus Hultén, 1996.

1955

Vårblandaren, våren, 1955

Vårblandaren was a box containing lose material referring to art in a Dadaist fashion. It is said that George Machunias, the Fluxus leader, later used this box-issue as a model for his own different kits. (32)

1955

Konstrevy, no. 1

In this issue, the inside of the front cover contains an advertisement published by the Galerie Samlaren, Stockholm, with the following caption, “marcel du champ, new york/hultén/.”The reason for Duchamp’s rare appearance in such an advertisement is somewhat mysterious. It can be some kind of tribute to the artist due to Hultén’s interest and appreciation of Duchamp’s work. At the time, Hultén was working for the Galerie Samlaren while editing KASARK, in which he repeatedly wrote about Duchamp. (33)

click images to enlarge

-

32. Boulevardkartongen,

Tvångsblandaren in a box, spring mcmlv (1955).

-

33. Konstrevy no.

1 1955.

-

34. Salamander no.

1, no. 2, no. 3 1955.

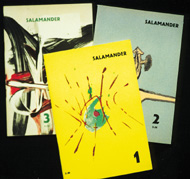

1955

Salamander no. 1

C. O. Hultén opened his Galerie Colibri, Malmö in January 1955 and the first issue ofSalamander was published that same year. Only three issues were published during the period of 1955-1956 (34). In the first issue is a translated fragment of André Breton’s text“Phare de la Mariée,” (Bruden som fyrbåk [Lighthouse of the Bride]), first published inMinotaur, no. 6, 1935. Ilmar Laaban and Ingemar Gustafsson (Leckius), both poets, did the translation. Three of Duchamp’s works appear in this issue.

Illustrations:

“Bruden som avklädd av sina ungkarlar, t.o.m. Glasmålning.” (“The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even [The Large Glass]”), S 404.

“Övergång mellan jungfru och brud,” Olja 1912. (“The Passage from Virgin to Bride”) 1912, S 252.

“Nio hanliga gjutformar, detalj ur glasmålningen,” (“Nine Malic Moulds, detail from the Large Glass.”)

There must be something wrong with the title of the later piece. If it actually is a detail from “The Large Glass,” a part of the water mill would be visible, but it is not, even though “Nine Malic Moulds” is a part of the bachelors region of the larger work. According to Schwarz, Duchamp made four versions of “Nine Malic Moulds.” The original version, done in 1914-15, S 328, was cracked in 1915. The second was made in 1934, and its present location is unknown, S 328 a. In 1938 Duchamp made a miniature reproduction of the work for “The Box in a Valise,” S 328 b. The third version was produced in 1963, S 328 c.Salamander was published in 1955 and shows a cracked “Nine Malic Moulds.” Therefore, this must be the original version that has belonged to Alexina Duchamp since 1956. In the catalogue from the Pasadena retrospective exhibition in 1963, there is a reproduction of the second version dated as 1963, with little similarity to the second version of the piece from 1934 in Schwarz, 1997.

You can also find Marcel Duchamp’s “SURcenSUR” originally published in L’ usage de la Parole, Paris, 1, no. 1, December, 1939, translated by Erik Lindgren, the poet, and Ilmar Laaban. This text is illustrated with Duchamp’s “Témoins Oculistes (Oculist Witnesses),” 1920, New York. S 383. It is now at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA).

Additionally, Ingemar Gustafsson (Leckius) has written a short biographical note about Duchamp.

This is the first time Duchamp’s major work “The Large Glass” was reproduced in Sweden. It is the original, which was later cracked during transportation from the Brooklyn Museum of Art in 1927. Now it too resides at the PMA, at Kathrine S. Dreier’s bequest.

There are several different versions of Duchamp’s “The Large Glass.” Among them is Ulf Linde’s version signed “pour copie conforme/ Marcel Duchamp/Stockholm 1961.” This version was exhibited in the Pasadena Art Museum, 1963.

The copy at the Tate Gallery, London was made by Richard Hamilton and signed “Richard Hamilton/pour copie conforme/Marcel Duchamp/1965.” A third copy can be found at the Art Museum of the College of Arts and Sciences, University of Tokyo, made in 1980.

A fourth replica was made in 1991-1992 by Ulf Linde, Henrik Samuelsson and John Stenborg and has been authorized by Alexina Duchamp.

1955

Konstrevy 3

In this issue, the art critic Bo Lindwall has published his article Marcel Duchamp-saboteur och anti-konstnär (Marcel Duchamp-saboteur and anti-artist). (35)

click images to enlarge

35. Konstrevy

no. 3 1955.

He writes the following: “His intellect is as sharp as a razor analyzing every given possibility to pieces. He started to detest all styles which he completely controlled, he found that even the most radical cubists yield to disgusting aestheticism, already towards a petrified academism. His creativity was paralyzed. The paralysis could not be stopped as long as he dreamt about renewing the art when he succeeded to convince himself that serious artistic activity was meaningless, then the paralysis disappeared. A coffee mill became his rescue in the first difficult crisis. 32 years ago he put down his brush for good. He is still alive.”

The coffee mill Lindwall refers to is “Coffee Mill” which Duchamp painted for his brother Raymond Duchamp-Villon’s kitchen, S 237. Since 1981, it has been at the Tate Gallery, London.

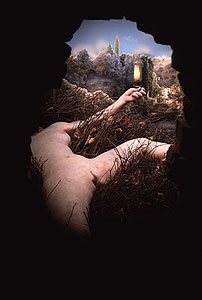

This piece is an important reference for Ulf Linde’s actual geometrical analysis of Duchamp’s last major work “Etant Donnés: 1 la chute d’eau/2 le gaz d’èclairage,” 1946-66, S 634. The piece is currently at the PMA. (But the latest news about this project is that Linde has left it unfinished.)

Illustrations:

Marcel Duchamp: “Porträtt av konstnärens fader,” 1910. (“Portrait of the Artist’s Father,” 1910), S 191, currently at the PMA.

“Sonaten (Konstnärens mor och tre systrar),” 1911, (“Sonata,” 1911), S 229, at the PMA, as well.

“Fresh Widow,” 1920, S 376, resides in the MoMA. There are two other versions of this piece; Ulf Linde’s of 1961, which is at the MMS, and Schwarz´s anniversary edition from 1964.

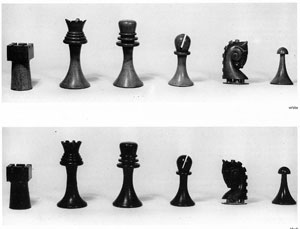

“Modeller till schackpjäser,” 1922. (“Chess Pieces,” 1918-19), S 377 is now at the MoMA.

“Ungkarlarna,” 1914, (“Cemetery of Uniforms and Liveries No. 2,” 1914), S 305, is currently at the Yale University Art Gallery.

“Monte Carlo,” 1924, (“Monte Carlo Bond,” 1924), S 406 (See above entry).

“Ready-made,” 1914 (“Bottle Dryer [Bottlerack],” 1914), S 306 (See above entry).

“3 Stoppages Étalon,” 1913, (“3 Standard Stoppages,” 1913-14), S 282. The original is at the MoMA while the replica made by Ulf Linde in 1963 is at the MMS. A replica from 1963 is at the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena.

“Förvandlingen från jungfru till brud,” (“The Passage from Virgin to Bride,” 1912), S 252, is currently at the MoMA.

(The titles in Schwarz latest catalogue raisonné and the Swedish captions do not always correspond.)

In the same issue, page 127, Konstrevy presents Denis René’s exhibition “Le Mouvement.” Pontus Hultén curated that exhibition together with Robert Breer and Jean Tinguely. A few of Duchamp’s mechanical works were represented, “… in some cases they have, as Duchamp used, clockworks or electricity to operate machinery.” The curators point out thatSamlaren’s exhibition in 1954,(see previous entry), was a forerunner to Denis René’s exhibition.

1955

Salamander, no. 2

In Salamander, no. 2 there is an article about Robert Matta written by James Thrall Soby where he suggests Duchamp’s influence on Matta. Soby refers to the Surrealist exhibition “First Papers of Surrealism” in New York, 1942. The author implies that Matta has been influenced by Duchamp’s Sixteen Miles of Strings, S 488, which ran back and forth in the exhibition. He continues, “The effect on his [Matta’s] paintings is more likely that Duchamp’s influence had a great impact.”

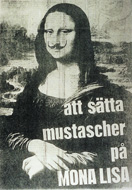

Sydsvenska Dagbladet (SDS), Tuesday, June

14, 1955

|

click to enlarge

|

|

|

|

36. Sydsvenska

Dagbladet, Tuesday, June 14 1955.

|

In this daily newspaper, Duchamp made an indirect appearance in Sweden in a print advertisement (36). Sellers & Co., an advertising agency, used this work to reach a new clientelle. They used the “Mona Lisa” with the headline “att satta mustascher pa MONA LISA” (to put a moustache on MONA LISA) and in a footnote, refer to Marcel Duchamp.‘”Why not be original?’ the Dadaist Marcel Duchamp thought in the 20’s and put a moustache on the Mona Lisa! Both Duchamp’s fantastic trick and Dadaism had a short lifetime like a dragonfly. How many, for example, today know anything about monsieur Marcel Duchamp’s herostratic creation of art?”

1955

KASARK no. 2. okt, 1955.

In this issue, K. G. Hultén (Pontus Hultén) presents “Art in Motion-Kinetic Art.” I think Hultén is the first one to write and point out this field of art. On the cover, printed in bold and light red capital letters is the following headline: “Om den ställföreträdande friheten eller om rörelse i konsten och Tinguelys metamekanik av Karl G. Hultén” (“The Substituted Freedom or About Art in Motion and Tinguely’s Metamechanic” by Karl G. Hultén). (37)

click images to enlarge

37. KASARK

no. 2, autumn 1955.

Hultén was one of the curators of “Le Mouvement” at Galerie Denise René in Paris, 1955 (See previous entry). Since then, Hultén has dealt with art in motion extensively.

(The best, concise information about his writings on this matter is in Das Gedruckte Museum von Pontus Hulten, 1996. There you can read about the exhibitions “Le Mouvement” Paris, 1955, “Marcel Duchamp, Bokkonsum,” Stockholm 1960, Rörelse i konsten (Art in Motion),” 1961, “The Machine,” MoMA, 1968, “Marcel Duchamp,” Centre George Pompidou, 1977, and “Marcel Duchamp,” Palazzo Grassi, 1992-3.)

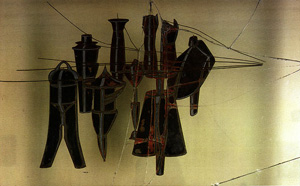

In this issue he makes an early attempt to introduce the importance of kinetic art, where Duchamp has played a major roll. On pages 7-13, Hultén presents Duchamp’s moving and mechanical works and as well as his defining role in the field.

Hultén’s article is illustrated with the following images:

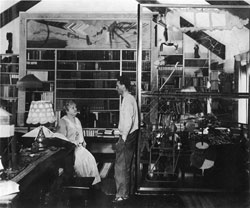

A photo of Duchamp’s studio in New York, where his “first readymade” is seen, a replica of “The Bicycle Wheel,” S 278, and, on the floor, “Trébuchet,” S 350.

“The Large Glass,” S 404, the cracked version in Katherine S. Dreier’s home.

Photos of the “Rotary Glass Plates (Precision Optics),” one in motion and one still, S 379, currently at the Yale University Art Gallery. In the article, the work is called “Rotary Glass Piaques,” which must be a printing error. It should be “Rotary Glass Plaques,” Duchamp’s first motor-driven object from 1920.

A photo of “Rotary Demisphere,” 1925, S 409. The work is currently at the MoMA.

Photos of three of Duchamp’s “Rotoreliefs,” 1935, S 441.

1956

AVANTGARDE-FILM, by Peter Weiss, Stockholm, 1956.

In his book, pages 21-40, Peter Weiss has a chapter about the avant-garde films in the 1920s. Included are Marcel Duchamp´s “Anemic Cinéma,” 1927, and his roll in René Clair´s “Entr’ acte,” 1924, in the famous chess party scene with Man Ray on a Paris rooftop. The text is illustrated with that scene and stills from Duchamp’s own film. (37 b)

click images to enlarge

37b. Avangardefilm,

1956

1956

Konstspegeln no. 3-4

This is a small and local art magazine published in the south of Sweden. In no. 3-4 Max Walter Svanberg writes about The Magic Art. He mentions the Dadaist, Duchamp. The article is illustrated with “The King and Queen Traversed by Nudes at High Speed” S 246 a, which is now at the PMA. In a special caption Svanberg makes the following remark,“Duchamp, is one of the most important and innovative artists according to the new direction of art, which in this article is called “the non geometrical abstractions.” (38)

click images to enlarge

-

38. Konstspegeln no.

3-4 1956.

-

39. KASARK no.

3 Maj (1958).

1958

KASARK no. 3. Maj 58.

In this issue, K.G.H. (Pontus Hultén) writes about collage or fantastic realities. On page 8, he points out that Duchamp used chance to create “3 Stoppages Étalon,” S 282. It is now at the MoMA. (39)

1959

Konstrevy no. 3

In his review “Utställningar i Stockholm, Mars – April” (Exhibitions in Stockholm March-April) Eugen Wretholm, mentions that Öyvind Fahlström uses chance similarly to Duchamp. This is probably the first time Duchamp’s influence on other artists is mentioned in Sweden. (40)

click images to enlarge

-

40. Konstrevy

no. 3 1959

-

41. KASARK no.

4 april 1960.

1960

KASARK no. 4. April, 1960.

This issue was published about the exhibition “Edition MAT” (Daniel Spoerri) at Bokkonsum in Stockholm, April 1960. (41)

Even in this issue, K.G.H. (Pontus Hultén) writes about Duchamp. The headline reads: “A Work of Art has No Price,” and continues to quote Duchamp, “Modern art looks for its Gutenberg.” Duchamp is presented as a, “Painter, poet, chess player, and a forerunner within Dadaism, Surrealism and kinetic art. In 1936, Duchamp exhibited his Rotoreliefs at the inventor’s exposition in Paris. Born in Blainville, France.” (See entry).

1960

Konstrevy no. 3

Eugen Wretholm writes about the exhibition at Bokkonsum, which he calls “Dadaistica.” He mentions Marcel Duchamp and reproduces his Rotoreliefs placed on the pavement in front of the gallery together with other items from Edition MAT.

1960

Bokkonsum

Saturday May 7, 1960, Bokkonsum opened an exhibition with some replicas of Marcel Duchamp’s readymades made by Per Olof Ultvedt and Ulf Linde (38). In Das gedruckte Museum von Hulten, 1996, page 83, the circumstances of this exhibition are described. Linde describes the event quite differently in his book Marcel Duchamp, 1986.

Page 10 of Marcel Duchamp contains a reproduction of the announcement card from Bokkonsum’s exhibit and other photographs taken on the occasion (42). In one, of the shop-window, there is a large copy of Eliot Elisofon’s photo from Life Magazine, April, 1952, of “Duchamp descending a staircase,” a paraphrase of his painting “Nude Descending a Staircase.” The same photograph was later used as the cover of the revised edition of Robert Lebel’s monograph Marcel Duchamp, published by Paragraphic Books, Grossman Publishers, New York, 1967. In that edition, Lebel extended his catalogue raisonné with little information about Duchamp’s appearances in Sweden.

The book also depicts Ulf Linde’s version of the “Bicycle Wheel,” 1960, S 278 c, now at the MMS. “Fresh Widow,” S 376, was made by a carpenter on Linde’s request and was later acknowledged and signed by Duchamp “pour copie conforme Marcel.” This version is now in the collection of the MMS. In his book from 1986, Linde calls it a readymade, but according to Schwarz, it is not. You can also see the “Chocolate Grinder, No. 2,” 1914, S 291. Additionally, there is a small version of “The Large Glass,” which Linde says, “happily disappeared.”

In the Bokkonsum’s show was also “Bottle Rack” which Daniel Spoerri had purchased at Bazaar l’ Hotel de Ville in Paris, and lent to the show. This copy is not mentioned in Schwarz.

click images to enlarge

-

42. Ulf Linde. “Marcel

Duchamp” 1986 p. 10, In and

outside Bokkonsum 1960

-

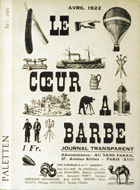

43. Paletten no.

3 1960.

1960

Paletten, no. 3

On page 91, they publish Marcel Duchamp’s The Creative Act, translated by Folke Edwards, the chief editor. This lecture was given by Duchamp at the Convention of the American Federation of Arts in Houston, April, 1957. On page 99 of the same issue, there is additional information about Duchamp as a contributor to this issue. (43)

1960

Spejare by Ulf Linde

Linde’s book Spejare (Searcher) (See 11) was one of the catalysts of the great artistic debate in Sweden later named “Är allting konst?” (Is everything art?). Perhaps it was one of Linde’s statements that awoke the most anger among artists and members of The Royal Academy of Arts, for Linde stressed Duchamp’s opinion that it is the viewer who creates the work. Duchamp’s opinion was already released in 1957 in his lecture The Creative Act.

Rabbe Enckell, chairman of the Royal Academy of Arts, actually started Sweden’s notorious art debate. He delivered a speech entitled, “Ikaros och lindansare, ett försvar för klassisismen, (Ikaros and Ropewalkers, a Defence for the Classicism)” to the academy on May 30, 1962. Thereby dissociating himself and the academy from the tendencies that he felt threatening to the order of art. This huge debate was later published in book called Är allting konst? (Is everything art?),Stockholm, 1963, with Duchamp’s “Bottle Dryer [Bottlerack],” on the cover.

It was not only Linde’s book that caused this violent turbulence in the Swedish art world. There were other art events, which in the beginning of the 1960s contributed to the debate. A specific catalyst was the purchase of Brancusi’s “Le Nouveaux-né,” 1961 from Rolf de Marée by the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, for the total of a 161,000 Swedish crowns. In 1961, this was considered an exorbitant amount for a modern artwork, and many thought that it was an excessive waste of museum funds.

Art in Motion and Four Americans

In 1961 K.G. Hultén, Carlo Derkert, Daniel Spoerri, and Billy Klüver opened one of the most important exhibition at the Moderna Museet called “Art in Motion,” from May 17th to September 3rd. Realizing that the exhibition would be a shock to the Swedish art public, it was first shown at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam from March 10th to April 17th. It was also shown at Louisiana, Humblebaeck, Denmark from September 22nd until October 22nd, 1961. (See Moderna Museet Stockholm 1958-1983, page 36, (See 4))

I can personally remember what a debacle it was when the Moderna Museet presented “4 Americans” in March of 1962. Robert Rauschenberg’s works created a scandal especially his “Monogram,” a longhaired goat with a painted face and a tire around his stomach. “The Bed,” a painted bed with cushion, sheets and a quilt hanging on the wall, raised the question if it could even be considered art.

It was during these two exhibitions that Linde’s concept of the viewer’s role gained its breakthrough, aided by the controversial publicity the shows had received. The issues were related. It was not odd that the conservative public and art critiques and artists were terrified, for, in a way, they had become obsolete.

1961

Konstrevy, no. 1

Öyvind Fahlström writes a review about Ulf Linde’s Spejare, 1961.

“The central point in ‘Spejare’ is the analyses of Marcel Duchamp’s large painting, [The Large Glass], which for the first time here is given the proper importance [compared with the confusion in connection with Duchamp’s exhibition at Konstsalongen, (Bokkonsum), Vallingatan.] ‘Spejare’ is the most stimulating and beautifully written book in Swedish which I have read.”

1961

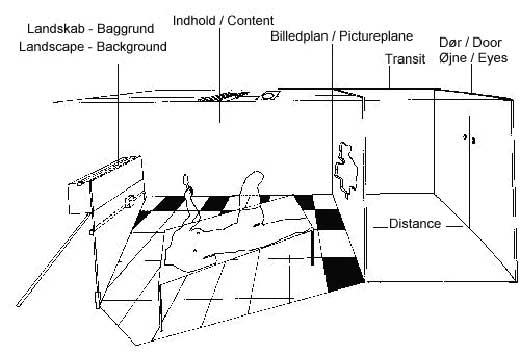

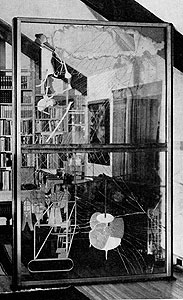

Rörelse i konsten, Moderna Museet, Stockholm 17 May -3 September, 1961, catalogue

This exhibition is one of the most important shows organized in the twentieth century (see 4). The committee consisted of K.G. Hultén, (Pontus Hultén), Carlo Derkert, and Daniel Spoerri and from the U.S.A., Billy Klüver. Pontus Hultén was editor of the catalogue in which he writes in the introduction,

“Contemporary art is often pessimistic, defeatist and passive; completely natural, one can say. But there is also an another kind of art. That is what this exhibition wants to show [dynamic, constructive, full of joy, confusing, ironical, humorous, aggressive]. It is probably even typical for our time.

“The 19th century exhibitions were visited by the same curious and interested masses of spectators that are currently visiting the motor shows. But will they, in the end, find what they are looking for? Apollinaire wrote in 1913, according to Marcel Duchamp, that only an art which is liberated from aesthetic concerns and which deals with energy as a pictorial material, can hope to ‘re-unite the Art and the People.’

“The camera is the machine to take a picture with, and is available to everyone. But there are other art machines, perhaps more independent, which also talk to us and tell us who we are. They appear in many forms and materials, sometimes they look like scientific research or camouflage themselves as toys.

“Kinetic art has, during the twentieth century, been developing in many different ways, at least equal in varying forms to static art. To use the physical movement as an instrument of expression gives it a freedom, which art has been trying to attain for a long time…

K.G. Hultén”

In the catalogue, there is a short dictionary about the artists working with kinetic art. The biographical note about Marcel Duchamp, mentions his first two readymades, “Pharmacy,” S 283 and “Flaskstället” (“Bottle Dryer ([Bottlerack],” 1914, S 306). (Refer to the below entry about Duchamp’s works in the exhibition.)

The catalogue quotes Duchamp, “I did not stop painting in order to play chess. That is a myth. It is always like that. Because someone begins to paint it does not mean that he must continue with that. He is not even forced to stop. He just does not do it any more, in the same way that you do not make omelets any longer, if you prefer meat. I do not think that it is necessary to classify people and, above all, treat painting as a profession. I do not understand why people try to do painters of civil servants and civil servants of the ministry of the fine arts. There are those who get medals, and those, who paint.”

There is also a short review about the history of kinetic art in the 20th century by K.G. Hultén. He begins with futurists artists, continues with Marcel Duchamp’s “Coffee Mill,” 1911, and ends the Duchamp presentation with his “Rotoreliefs” made in 1936.

Nine of Duchamp’s important kinetic works were shown at “Art in Motion” in addition to “Boite-en-valise” which was represented at the show. Therefore one can say that all of Duchamp’s major works were present. For in fact, “Boite-en-Valise” represents a retrospective exhibition in a small suitcase. That was the first time Duchamp’s works were presented to a larger public in Sweden, perhaps for the first time in the world, without being related to Cubism, Futurism, Dadaism, and Surrealism. If this was actually his major breakthrough in the context of Swedish art, is yet to be decided. Though he did become absolutely accepted by the institutional art world at that time, his standing today is another question.

Works by Duchamp in the exhibition:

“Cykelhjulet,” 1913, reconstruction, (“Bicycle Wheel”), S 278c.

“Chokladkvarn, No. 2,” 1914 (“Chocolate Grinder No. 2”), S 291.

“Naken går nedför en trappa, No. 3,” 1916 (“Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 3”), S 343.

“Bruden avklädd t.o.m. av sina ungkarlar,” 1915-23, reconstruction, 1961 (“The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even [The Large Glass]”), S 404.

“Rotary Glass Plaques (Optique de Precision),” 1920, reconstruction, 1960 (“Rotary Glass Plates [Precision Optics]”), S 379.

“Demisphère Rotative (Optique de Precision),” 1925 (“Rotary Demisphere [Precision Optics]”), S 409.

“Skivor med ordspråk,” 1926 (“Anemic Cinema: Disks Inscribed with Puns”), S 415-23.

“Dörren i 11, rue Larrey,” Paris, 1927, reconstruction, 1960 (“Door: 11, rue Larrey”), S 426.

“12 Rotoreliefer,” 1935 (“Rotoreliefs [Optical Disks]”), S 441.

“Boite-en-Valise,” (From or by Marcel Duchamp or Rrose Sélavy [“The Box in Valise”], 1935-41), S 484.

For the exhibition “Rörelse i konsten” (“Art in Motion”) in Amsterdam and Stockholm, Pontus Hultén, Per Olof Ultvedt and Magnus Wibom made a replica of “Rotary Glass Plates (Precision Optics),” S 379. Hultén and Daniel Spoerri made a replica of “Door: 11 rue Larrey,” S 426. It was destroyed after the exhibitions. (See 4)

1961

Konstrevy, no. 3

On page 99, is an article about “Art in Movement” at the Moderna Museet, illustrated with a photo of Duchamp visiting Iris Clert’s gallery in Paris.

In Eugen Wretholm’s review “Utställningar i Stockholm” (Exhibitions in Stockholm), page 112, Duchamp’s “Fountain” and “Bottle Dryer [Bottlerack]” are mentioned. You can also find Umbro Apolloninos’ article “The Inner Movement” where he refers to Duchamp and uses “Nude Descending a Staircase” as an illustration.

1961

Konstrevy no. 4

Eugen Wretholm writes about “Art in Motion” once again, where he mentions Duchamp’s “Nu Descendant un Escalier.” He remarks that the exhibition originated in Paris as “Le Mouvement” at Denis René by K.G. Hultén and refers to his text about “Art in Motion” inKASARK 3, October, 1955.

1961

Konstrevy, no. 5-6

Ulf Linde writes the essay Framför och bakom glaset (In front of and behind the glass) pages 162-165 (44). This is an important article about Duchamp’s “The Large Glass”. It is illustrated with six photographs taken of the assembling of Linde’s first reconstruction of “The Large Glass” together with Duchamp. The essay is a partial interview with Duchamp.

The other illustrations are:

Marcel Duchamp photographed as a woman by Man Ray. The correct title as listed in Schwarz’s text is “Marcel Duchamp as Belle Halleine,” photo Man Ray, 1921, S 385.

“Chocolate Grinder no. 2.” S 291.

“The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even,” S 404, 1915-1923. Currently, it is at the PMA.

Page out of “Boite Verte, The Green Box.” A box containing 93 notes, drawings, photographs, and/or facsimiles by Duchamp housed in a green-flocked cardboard box, 1934, S 435.

On pages 224-227, Öyvind Fahlström writes about “The Art of Assemblage” at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and he mentions Duchamp’s last painting “Tu m´,” S 354. The work is currently at the Yale University Art Gallery. His article is illustrated with the version of “Bottle Dryer [Bottlerack]” on a table, photographed by Man Ray and sent in by Duchamp to the Museum of Modern Art exhibition, 1936-37.

click images to enlarge

-

44.

Konstrevy no. 5-6 1961.

-

45. Paletten no.

1 1961

1961

Paletten, no. 1

Paletten no. 1, 1961, published an article Marcel Duchamp: Anti-Artist by Harriet and Sidney Janis and translated by Folke Edwards, chief editor. (45)

This article is richly illustrated with major works from Duchamp’s production.

“Bride,” 1912, S 253.

“Coffee Mill,” 1911, S 237.

“Rotoreliefs,” 1935, S 441.

“Bicycle Wheel,” 1916, (1913), S 278.

“Marcel Duchamp,” portrait by Man Ray, 1920, or “Marcel Duchamp as Belle Haleine,” S 385.

“L.H.Q.O.Q.” 1919. The correct title is “L.H.O.O.Q., 1919, Paris,” S 369.

“Bachelors,” 1914. Properly titled “Nine Malic Moulds,” S 328. It is hard to see which version it is because the editor has only reproduced a part of the original. It seems to be the original version that Duchamp had made in 1914.

“The King and Queen Traversed by Nudes at High Speed,” 1912, S 246.

“Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2,” 1912, S 242.

“Bottle Dryer [Bottlerack],” 1914, S 306. This photograph is another version taken by Man Ray in 1936. It has both a shadow and a white reflection below its base. The photograph appears to have been retouched.

“Trois Stoppages Étalon (3 Standard Stoppages),” 1913-14, S 282.

“La Mariée mise a nu ses clélibataires, meme,” 1914-1923, S 404. The cracked version in Katherine S. Dreier’s home.

“Fresh Widow,” 1920, S 376.

“Tu m´,” 1918, S 354.

“Roterande glasplattor (Precisionsoptik),” 1920. The correct title is “Rotating Glass Plates

(Precision Optics),” S 379.

“Chocolate Grinder No.1,” 1913, S 264.

1961

Paletten, no. 2

In this issue Elisabet Hermodsson, artist and poet, refers to Linde’s book Spejare. Her contribution is titled “Critics as a Benefit Moralist” and she quotes Linde: “By itself nothing is art. First you have to call it art, see it as a work of art.”

Linde replies in the same issue in his discussion of Duchamp’s readymade “Why not sneeze”. He writes, “You have to do something with the art work, that it could ‘be’ art.”Hermodsson’s reaction was typical among the conservative artists in Sweden who were afraid of losing their territory within the art world.

The editor, Folke Edwards comments on the exhibition “Art in Motion.” He notes that many of the pioneers of kinetic art participated in the exhibition and considers Duchamp a representative for Futurism, Constructivism, and Dadaism.

1961

Rondo no. 3

Öyvind Fahlström comments on Duchamp’s “SurcenSur” and notes that “Duchamp has, as usual, done it before,” page 27. (46)

click images to enlarge

46. Rondo

no. 3 1961.

1961

Paletten no. 3

Torsten Andersson, the painter, contributes the article One Price Store Culture or Artistic Dictatorship. He writes “In the shadow of Duchamps… I don’t stop any man in the world by presenting a ‘Bottle Dryer [Bottlerack]’ or let the public fire a pistol.”

1962

Konstrevy no. 1

In this issue, Linde begins to present his translation of Duchamp’s notes on “The Large Glass”, S 404. The notes 1-11 are published and are illustrated with sketches from the “Green Box.” S 435. (47)

click images to enlarge

47. Konstrevy

no. 1, 1962. In this issue, Ulf Linde begins his translation of

notes from “The Green Box”

1962

Konstrevy, no. 2

In this issue Linde continues his translation of Duchamp’s notes about “The Large Glass”, notes 12-33. It, too, is illustrated with sketches from the “Green Box.”

1962

Konstrevy no. 3

In this issue Linde continues his translation of Duchamp’s notes about “The Large Glass”, notes 34-39. It is illustrated with sketches from the “Green Box.”

1962

Konstrevy, no. 4

In this issue Linde continues his translation of Duchamp’s notes about “The Large Glass”, notes 40-48. It is illustrated with sketches from the “Green Box” and a photo of “Nine Malic Moulds”.

Under the review “Exhibitions in Paris”, is a note about an exhibition at Galerie L’Oeil where they showed the art magazine Minotaur. Included in the works mentioned, are Marcel Duchamp’s “The Green Box” and “Rotoreliefs.”

1962

Konstrevy, no. 5-6

In this issue Linde ends his translation of Duchamp’s notes about “The Large Glass”, notes 49-78, which he produced in collaboration with Malou Höjer. It is illustrated with sketches from the “Green Box.” This contains 93 notes on “The Large Glass.” In Art Review No. 1, 1963, he publishes his comments on the subject. (See entry below.) (48)

click images to enlarge

48. Konstrevy

no. 5-6 1962. In this issue, Ulf Linde ends his translation

of “The Green Box”.

1962

Paletten, no. 4

C. G. Bjurström writes “Artworks and Things” where he discusses Linde’s interpretation of Duchamp’s “Bottle Dryer [Bottlerack].”

1963

Konstrevy no. 1

Here you find Ulf Linde’s essay Kommentar till Marcel Duchamps Bruden avklädd av sina ungkarlar, t.o.m. (Comment to Marcel Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even). It is illustrated with drawings from the “Green Box” and photographs of Marcel Duchamp taken by Lütfi Özkök in Stockholm, 1961. (49)

1963

Konstrevy, no. 2

This issue contains a full size advertisement of Marcel Duchamp’s exhibition at the Galerie Eva af Burén April – May, 1963. Illustrated by a photograph of Duchamp’s “Female Fig Leaf,” S 536. (50)

click images to enlarge

-

49. Konstrevy no.

1, 1963, Comments on Marcel Duchamp´s ”

The Bride Stripped Bare

by Her Bachelors, Even.”

-

50. Konstrevy no.

2, 1963, Female Fig Leaf. Advertisement

for Galerie Eva af Burén.

-

51. Anthology: Är allting

konst?, 1963.

1963

Är allting konst?

A collection of contributions to the debate Is everything art? published by Tribunserien, Bonniers, 1963. (See above.) Ulf Linde’s reply to Torsten Bergmark’s criticism is perhaps the sharpest and clearest I have ever read. (51)

1963

Galerie Eva af Burén – Marcel Duchamp

Ulf Linde released his book Marcel Duchamp, (52) in connection with Duchamp’s exhibition at Galerie Eva af Burén, Stockholm, 1963, of replicas of his ready-mades. Linde begins his text with an odd request, “I must ask the reader not to read the text – it is secondary. It is the captions, which are primary. I must ask you to read them first.”

This is the first book published in Sweden concerning the complexity of Duchamp’s works. One receives a glimpse of Duchamp’s aesthetics and anti-aesthetics views that he has used since distancing himself from retinal art.

In Linde’s 1987 book, he explains how his first book, Marcel Duchamp, 1963, finally came to be published. Initially, Linde’s text was written by request from Marcel Duchamp, forMetro, a very exclusive magazine in Milan, which had offered Duchamp 32 pages in issue no. 9. Duchamp, who had read Linde’s text in Spejare, asked the author if he could take care of the text for Metro by using the content from Spejare, adding only a few corrections and perhaps a new text. Duchamp wanted Linde to emphasize his ready-mades and use a few of his own writings of which Linde could make his own choice. Ulf Linde’s text was never published in Metro, but he began to plan its publication.

The issue of finances was solved when Duchamp offered his “Self-Portrait in Profile” in a special edition of 25 copies (53). It sold well and covered a part of the printing costs, S 557 b. An unnumbered edition was also published in regard to the Galeria Eva af Burén exhibition.

The show actually began when Linde visited Galerie Burén. During the call, he began discussing ways to display Duchamp’s “Boite en Valise.” Eva af Burén had purchased the work and wanted to exhibit it at her gallery. She wanted to consult the possibilities with Linde. “After a while we had planned an exhibition, which should contain replicas of almost every readymade by Duchamp. Only two were available in Stockholm – Bicycle Wheel and Fresh Widow, both signed by him when he was here [1961] – but one could ask Duchamp to manufacture the rest. – We wrote to Duchamp and received an immediate reply.” (See above.)

In total, there were nine replicas made for the show. They are now in the collection of the Moderna Museet, Stockholm, as a gift from the Friends of the Moderna Museet.

Replicas made for the exhibition at Burén:

“3 Stoppages Étalon” by Ulf Linde, 1963. Signed 1964 in Milan. S 282 a.

“Bottle Rack” by Ulf Linde, 1963. S 306 e, not signed.

“Le Peigne” by Ulf Linde, 1963. Signed in Milan, 1964, S 339 a.

“A bruit secret by Ulf Linde, 1963. Signed in Milan, 1964, S 340 a.

“Air de Paris” by Ulf Linde, 1963. Signed in Pasadena, 1963. Signature lost at Louisiana, Humlebæck, 1975. S 375 c.

“Fountaine” by Ulf Linde, 1963. Signed in Milan, 1964. S 345 c.

“…pliant de voyage…” by Ulf Linde, 1963. Signed in Pasadena, 1963. S 341 a.

“Why not sneeze?” by Ulf Linde, 1963. Signed in Milan, 1964. S 391 a.

“In Advance of the Broken Arm” by Ulf Linde, 1963. S 332 b.

Replicas Made for Bokkonsum:

“Bicycle Wheel” by P. O. Ultvedt and Ulf Linde, 1960 for Bokkonsum, signed in 1961. S 278 c.

“Fresh Widow” by P. O. Ultvedt and Ulf Linde, 1960, for Bokkonsum, signed in 1961. S 376 a.

“La mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même” by Ulf Linde 1961. Signed in Stockholm, 1961 for “Art in Motion.” S 404 a.

Other works by Duchamp at Moderna Museet

“Cœur volant.” S 446 c.

“Rotorelief.” S 441.

“Rotary Glass Plaques” replica by P. O. Ultvedt, M. Wibom and (K. G. Hultén). S 379 a.

“Objet Dard,” 1951. S 542.

(Source: Katalogen Moderna Museet, 1976.)

“Pharmacie” replica by Marcel Duchamp, 1963. Gift of Ulf Linde, 1977. S 283.

(Source: Supplement, catalogue, Moderna Museet, 1983.)

“Marcel Duchamp” by Ulf Linde, edition de luxe published by Eva af Burén, 1963. S 557.

“Bouche-évier, Cadaqués,” 1964. S 608.

“Étant donnés le gaz d’clairage et la chute d’eau.” Esquisse, is a gift from Thomas Fisher. S 526.

“Étant donnés le gaz d’clairage et la chute d’eau.” Gift from Thomas Fisher. S 531.

“La machine célibataire,” model made by Håkan Rehnberg, 1984. It is not in Schwarz.

“Le surréalisme même.” S 548.

Statens Konstmuseer, Stockholm

“Boite en valise,” Statens Konstmuseer. S 435.

“A l’infinitif,” Statens Konstmuseer. S 637.

“Prière de toucher,” Statens Konstmuseer. S 521-523.

(Source: Catalogue Marcel Duchamp, Moderna Museet, Stockholm, 1986-1987)

1963