|

A closer examination

of Duchampís 1964 urinal etching shows that, although Duchamp did base

his tracings on the Stieglitz photograph to create this etched image,

he, also and importantly, added a separate and specific extra part --

in a yet another perspective view, more radically different from the

rest. Note, when comparing illustration 46A, B and C with 47A and 47B,

the extreme leftward position that the whole urinal would have to occupy

(47B) for us to see this one urinal part in the upper right side (47A).

Why else would Duchamp move so far away from traditional perspective

in one exaggerated and isolated part of this drawing, if not from a

desire to push his point further, probably because we are likely not

yet again to notice his new rehabilitated perspective system based upon

fusions of multiple points of view in his drawings, models or photographs.

Remember this etching was done at the end of his life, in 1964. Duchamp

had already exposed his new perspective system to the world since his

1912 Chocolate Grinder painting and no one noticed. Moreover

we continue to not notice because the mind creates and depends on such

composites of information that Duchamp was presenting as perspective

all the time.

|

click

each image to enlarge

|

|

|

|

|

|

Illustration

46A.

|

Illustration

46B.

|

Illustration

46C.

|

|

Stieglitz

version of Duchamp's Fountain urinal

|

Etching,Marcel

Duchamp, An Original Revolutionary Faucet: Mirrorical Return,

1964 © 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris

|

An

overlay of Duchampís etching (1964) when flopped , and placed

onto the Stieglitzís photograph of Duchampís Fountain (1917)

indicates that used a tracing method.

|

|

|

click

left image to enlarge; click right image for animations

|

|

Click

to see a video of our animation analysis, comparing the 3D model

made from the idealized Stieglitz urinal (without

the distortions in the original photo) that Duchamp

draws with the varied positions that it would have to occupy to

match the multiple perspective descriptions contained within the

etching.

|

|

|

|

Illustration

47A.

|

Illustration

47B.

|

|

Video of

Urinal animation analysis based on the 1964 etching.

Note: Extra perspective part Duchamp added to Stieglitz urinal

image for his Etching, as well as how far turned to the left,

the urinal would have to be turned to see the perspective view

of this added part.

(Animation created by Gregory

Alvarez and Rhonda Roland Shearer.)

|

Given Duchamp's claim

that he studied the entire section on perspective at the Parisís main

library, and that, it is a "no-brainer" to trace the basic

shape of the Stieglitz urinal without mistakes, it would be difficult

to believe that this extra and distinct perspective part added by Duchamp

to his urinal etching, would have occurred through accident or incompetence.

We are especially encouraged to conceive of Duchamp's extra perspective

piece as intentional, since the rest of the etching captures the spatial

relations of the Stieglitz photo so well, including the pipe hole offset

to the left, and so forth.

I must add one final

point to buttress my case about the urinal. In the quotation on perspective

that I cited at the beginning of this essay, Duchamp claimed that he

added language, in addition to anecdote, in his rehabilitated form of

perspective. Bonnie Garner suggested that when Duchamp signed his urinal

Mutt, he, in effect, communicated linguistically the same structure

that he used geometrically (with his fusing of multiple perspective

parts into one whole). For what else is a "mutt" than an entire

mongrel dog composited of many dog breeds (or parts) put together in

time -- an entity that only appears to be, in a traditional perspective,

a low quality whole.

|

click

to enlarge

|

|

|

Illustration

48.

|

|

Cover of

The Blind Man, No. 2: P.B.T., 1917.

Just as Duchamp did with the Urinal, Duchamp combined the Chocolate

Grinder with the title of the journal, The Blind Man.

|

The other colloquial

definition of mutt as "a stupid person" brings me back

to thoughts about the first appearance of Duchampís urinal in The

Blind Man (1917). Not only was the Mutt urinal essay and image placed

under The Blind Man heading, but Duchamp and his close friends

also(and, I believe, not coincidentally) used Duchampís Chocolate

Grinder painting on the front cover, under The Blind Man

banner, as well -- see illustration 48.

I argue that this

placement of the Chocolate Grinder painting with the Blind

Man heading relates directly, in meaning, to Duchampís similar positioning

of his urinal. For as spectators in 1917, we would have been specifically

blind to Duchampís new rehabilitated perspective used in both

his Fountain urinal and Chocolate Grinder forms,

as well as generally blind, as a consequence our foolish dependence

(as Duchamp believed) on conventional perspective and "retinal

vision" for determining factual reality.

My discovery

that the strangely distorted Chocolate Grinder uses the same systematic

characteristic approach also found in the hatrack, coatrack and urinal

(and a large set of other examples not discussed in this essay) returns

us to Duchampís words that I used at the beginning of this essay --

a quotation that now bears repeating.

| Duchamp: |

Perspective

was very important. The "Large Glass" constitutes a rehabilitation

of perspective, which had then been completely ignored and disparaged.

For me, perspective became absolutely scientific. |

| Cabanne: |

It was no longer realistic perspective. |

| Duchamp: |

No.

Itís a mathematical, scientific perspective. |

| Cabanne: |

Was

it based on calculations? |

| Duchamp: |

Yes,

and on dimensions. These were the important elements. What I put

inside was what, will you tell me? I was mixing story, anecdote

(in the good sense of the word, with visual representation, while

giving less importance to visuality, to the visual element, than

one generally gives in painting. Already I didn't want to be preoccupied

with visual language. . . . |

| Cabanne: |

Retinal. |

| Duchamp: |

Consequently,

retinal. Everything was becoming conceptual, that is, it depended

on things other than the retina. |

Duchampís claims in

this interview (albeit cryptically) that he has done something rigorous

and different to rehabilitate perspective, and that he has embodied

this novelty in his new geometry in the Large Glass -- with the

Chocolate Grinder as one part!

In 1956 Duchamp stated

"I was already beginning to make a definite plan, a blueprint for

the Large Glass. All of this was conceived, drawn, and on paper

in 1913-14. It was based on a perspective view, meaning a complete knowledge

of the arrangement of the parts. It couldnít be haphazardly done or

changed afterwards. It had to go through according to plan, so to speak."

In the Cabanne interview Duchamp further claims that "I had worked

eight years on this thing, (the Large Glass) which was willed,

voluntarily established according to exact plan. . ."

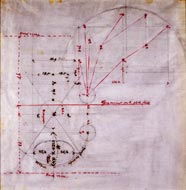

Duchamp carefully

provided us with his "Sears Roebuck-like" catalogue of notes

and drawings describing his Large Glass project. Mostly written

between 1911-15, these notes include a separate plan view and a side

elevation of the lower "bachelor half" of the Large Glass,

(but no 3-D model) and a perspective drawing illustrating measurements

at 1/10 scale of the final Large Glass work, see illustration

49A, B, C,D.

|

click

each image to enlarge

|

|

|

|

|

|

Illustration

49A.

|

Illustration

49B.

|

Illustration

49C.

|

Illustration

49D.

|

|

Perspective

view,

The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even,

1915-23

©

2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris

|

Plan section of Bachelor Apparatus: Facsimiles of Plan and

Elevation, 1913/1934 © 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp,

ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris

|

Elevation

section of Bachelor Apparatus: Facsimiles of Plan and Elevation,1913/1934

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris

|

Perspective

drawing, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even,

1913 © 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris

|

Architects or engineers

depend upon similar plan views and side elevations as Duchampís Bachelor

half to manufacture 3-D projects and small scale 3-D models. As discussed

earlier, perspective drawings, in contrast, indicate the relative position

of a particular observer in visual relation to the object or building.

A "precise and exact aspect" in the science of perspective

(an "aspect" that Duchamp said he was interested in following),

dictates that the perspective in the lower half of the Large Glass

drawing should relate to the geometry of the "blueprint" plan

and elevation. In other words, if you make a 3-D model following Duchampís

plan view and side elevation blueprints, you should readily be able

to find and replicate the perspective view that Duchamp depicts in his

perspective drawing by using this very same 3-D model.

Most Duchamp scholars

have either accepted or praised Duchampís perspective skills. The problem

remains, however, that I and a few other scholars have actually made

3-D models from Duchamp's plans -- and none of us can find any one

perspective projection view that matches Duchampís perspective drawings!

Moreover, the process of trying to recreate the Large Glass perspective

drawing from what a viewer would see of the 3-D model via perspective

(equivalent to what one eye or camera lens sees) quickly becomes maddening.

When you fit one part of the Large Glass model to its projection

in Duchampís perspective drawing (say; part A, the ellipse in one wheel

of the Chocolate Grinder, for example -- see illustration 49A),

the rest (parts B through Z) immediately fall out of place. We lose

the fit of part A, and all the other parts C through Z, once part B

is matched -- etc.

We may then be tempted

to somehow change the plans so that the perspective projection, as laid

out in Duchampís actual Large Glass, can be generated from the

3-D model (built from the plan and elevation view) -- which is, in fact,

what some scholars have done. But thatís cheating, and such a providence

also assumes that Duchamp was incompetent, or did not care about accuracy

of perspective, although he claimed otherwise in earlier interviews,

as well as to Cabanne.

If both the plan view

and side elevation construct a consistent 3-D model of the Chocolate

Grinder and the overall Large Glass itself, how and why have

I and other scholars failed to generate a similar, if not exact, perspective

drawing from this 3-D Large Glass model? I will argue that the

reason why we cannot generate a single perspective view (in duplicating,

what should has been the process that Duchamp followed to create his

perspective drawing) must be Duchamp himself did not used perspective

geometry, but, rather his new rehabilitated perspective -- the method

that created his perspective drawing and the Large Glass (a.k.a.

The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even 1915-23.)

|

click

each image to enlarge

|

|

|

|

|

Illustration

50A.

|

Illustration

50B.

|

|

Cube

seen in 2D parts

as eye moves around it

|

Perspective

distortions

of cube in relation to fixed eye

|

If we analyze the

parts of the Large Glass (a 2D perspective view), using a 3D

model constructed from Duchampís plans, we can only duplicate the depictions

in what is rendered in Duchampís Large Glass 2D perspective drawing

when we move our eye in time around the Large Glass 3D model

to collect snapshots (cuts), and then fuse these separate perspective

parts together into one depiction -- the very same method that Duchamp

uses in his coatrack, hatrack and urinal 2D representations. Recall

the illustrations (now #50A,B) showing the different perspective depictions

resulting from 4 different fixed eye positions, in contrast to an eye

that moves around a cube.

Illustration 51A,

B, C present three animations from our analysis of Duchampís Chocolate

Grinder and Large Glass in 2D and 3D. The first animation

(51A) shows the cameraís perspective while moving around a 3D model

of the Chocolate Grinder in 3D space. Colors highlight the part

that corresponds to the equivalent section of the 2D Chocolate Grinder

in the Large Glass perspective drawing. In other words, the animation

shows a position that both the camera and 3D Chocolate Grinder

would have to occupy to create the particular 2D Chocolate Grinder

part shown in color code.

|

click

each image and see animations

|

|

|

|

|

|

Illustration

51A.

|

Illustration

51B.

|

Illustration

51C.

|

|

Three

animations from our analysis of Duchampís Chocolate Grinder

and Large Glass in 2D and 3D

(created by Gregory

Alvarez and Rhonda Roland Shearer)

|

The next animation,

51B, shows our 3D computer model of the Chocolate Grinder as

fundamentally based upon Duchampís 1913/1934 plan view and side elevation

plans. The animation further depicts how the position of the camera

determines the particular set of distortions seen by the lens in any

one 2D snapshot of the 3D Chocolate Grinder. Moreover, this animation

depicts that once one camera position allows a match in one part of

the Chocolate Grinder, the other parts of the Chocolate Grinder

and the Large Glass depart from this single perspective position.

When other Chocolate Grinder parts are matched, each exists in

its own perspective framework. Our efforts to tame all Chocolate

Grinder parts into one perspective view, slips hopelessly away with

each successful match of a single part, and the consequent complete

rejection of the rest in lock step.

|

click

to enlarge

|

|

|

|

|

Illustration

51D.

3D

model

|

Illustration

51E.

2D

composite

|

|

|

Due

to perspective constraints, we would have to move one eye or lens

in 3D space and time approximated 43 times around the 3D model

to actually see the same information as Duchamp shows us in his

Large Glass work in only one instant.(Created by Gregory

Alvarez and Rhonda Roland Shearer

|

|

The next animation

sequence, 51C, illustrates the cut and paste method that Duchamp probably

used to create not only his Chocolate Grinder (and also his coatrack,

urinal, hatrack, etc.), but the entire bottom half of the Large Glass

itself. As any one photograph yields a single perspective view (with

its own particular distortions), Duchampís selection of one part from

each snapshot, after he pastes them together, creates a multiple fusion

of varying perspectives. The last frame, showing the Large Glass

in color coding, indicates each of the (approximately) 43 parts that

live in their own perspective world, see Illustrations 51D and 51E.

Due to perspective

constraints, we would have to move one eye or lens 43 times in 3D space

to actually see the same information that Duchamp shows us in his single

Large Glass work! Illustrations

51F and 51G map the 43 camera positions in relation to the Large

Glass 3D model that produced the 2D color coded projections in 51D

and 51E.

|

click

to enlarge

|

|

|

|

|

Illustration

51F.

|

Illustration

51G.

|

|

Side

view of set of 43 possible camera positions Duchamp used to create

his Large Glass fusing approx 43 photo parts cut from photographs

in 43 different perspectives.

|

Top

down view of set of 43 possible camera positions Duchamp used

to create his Large Glass fusing approx 43 photo parts

cut from photographs in 43 different perspectives.

|

|