|

|

Click

to see video

|

|

|

Illustration

27.

|

|

Video

of Coatrack

animation analysis

|

In order to actually

see all of the coatrack information seen in Duchamp's original studio

photograph in real 3D space, our eye would need to be moving in time

-- see Illustration 27 showing a video of Robert Slawinski and my animation.

Our analysis of the original coatrack depiction reveals that Duchamp

used a common composite photo trick to "cut and paste" together

his "whole" coatrack. Using 6 different photographs from 6

different fixed eye viewpoints, we believe that Duchamp cut out one

section of the coatrack from each photo and then carefully fused these

parts together for the final appearance of only one readymade coatrack.

The spectator would only "see" this actuality of multiple

points of sight "non-retinally," with conscious effort via

mental visualization or actual model-making.

We made both physical

and computer models here in the lab. Our computer animation diagrams

the 6 cuts we believe that Duchamp made from 6 separate photographs

taken in 6 different perspective positions. Robert Slawinski and my

analysis concludes that Duchamp used 3 whole hooks, 1 hook split into

2 parts and 1 whole wood board as the 6 parts (from 6 different photos)

as he assembled into what appears to be the single, whole and readymade

coatrack in his studio photograph. See Illustrations 28A, B, C, D, E,

F, the 6 coatrack parts that Duchamp cut out and later assembled together

are color coded (in these still images taken from the computer animation)

to emphasize the separation of the part selected by Duchamp from the

rest of the coatrack (that he then discards, and that follows the same

perspective geometry of the targeted part.)

|

click

each image to enlarge

|

|

|

|

|

28A

|

28B

|

28C

|

|

|

|

|

28D

|

28E

|

28F

|

This

series of stills shows each of the 6 coatrack positions

from which Duchamp selected parts to composite

(Note: The selected parts are color-coded)

|

Click

each

image to enlarge

|

|

|

Illustration

29A.

A color-coded diagram showing the 6 parts

Duchamp composited together taken from 6 photos.

|

|

|

Illustration

29B.

|

|

This

still from our coatracks from which Duchamp selected parts to

composite (as in 29A).

|

Illustration 29A and

B show a comparison of the parts that Duchamp selected (in color coding)

with an image that assembles the 6 whole coatracks, in their 6 different

perspectives, together into one event simultaneously seen (using the

same color coding).

In addition to the

evidence resulting from our analysis of the perspective geometries,

2 other examples of internal evidence indicate that Duchamp used both

"masking" and "cut and paste" techniques from the

photo alterations used in hobby and trade.

|

Click

to enlarge

|

|

|

Illustration

30.

|

|

A

photo trick book points to the problem of "fluffy contours"

created by the unintentionally cut and paste method, revealing

that photo compositing has been made.

|

Examine illustration

30, a close up view of Duchamp's original coatrack photo, revealing

what a photo trick book calls the "fluffy edges" that can

easily appear as a soft whitish outline around a photo cut-out after

being pasted, if special measures are not taken. Forensic experts look

for tell-tale signs -- such as fuzzy contours

-- as indicators that photo prints have been combined. See illustration

31A and B,two pages from "The Secrets of Trick Photography"

by O.R. Croy discussing this particular problem within the cut and paste

method.

|

Click

each

image to enlarge

|

|

|

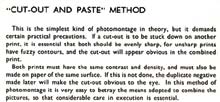

Illustration

31A.

|

|

|

Illustration

31B.

|

|

Here

are two pages from a photo trick book discussion about the "cut

and paste" method used for creating photo composites.

|

Our second example

of internal evidence for our hypothesis that Duchamp altered his original

coatrack photograph by combining parts returns us to illustration 23E.

Only after making our animation analysis of the geometries in the coatrack

did I notice the potential importance of Duchamp's "working"

prints of the coatrack first published in 1983 by Ecke Bonk. These prints

were described by Bonk as preliminary stages of Duchamp's 1940 process

in preparing pochoir prints for his publication of 300 copies of the

Boîte-en-valise, (see illustration 32A and B). Bonk does

not explain what the method was, or why Duchamp was cutting and pasting

a separate paper cutout of the coatrack onto the background studio photo

(where 3 hooks are masked out of the scene with white). Illustration

32B indicates an attempt to position only the first hook of the cutout

onto the coatrack underneath. This "working print" also suggests

(as judged by their two positions) that the paper cut-out coatrack is

in one perspective view and the coatrack underneath, imbedded into the

studio photo background, is in another perspective.

|

Click

each

image to enlarge

|

|

|

Illustration

32A.

|

|

Marcel

Duchamp, Boite-Series F, 1966

© 2000 Succession

Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris

|

|

|

Illustration

32B.

|

|

Working

print used by Duchamp to create his 1941 pochoir print for the

Boite-en-valise

|

|

|

Illustration

32C.

|

|

A

still from our coatrack analysis that appears strikingly similar

to Duchamp's working print above

|

Compare this working

print (32B) to our still from the video animation, where we concluded

that Duchamp used 6 different viewpoints (cutouts of hooks and a wood

board from 6 photographs), see illustration 32C. The similarity between

32B and C is striking. Was Duchamp using the same method of compositing

multiple viewpoints into one coatrack for his pochoir print that he had

used earlier to create his original coatrack in the studio photograph?

I believe that this

working print serves as a "smoking gun" in our case. Not only

is the cut and paste method and the geometries of the forms similar

between the alterations in the studio photograph and in Duchamp's Boîte

pochoir print, but his separate white-out and maskings of the wood board

and the hooks now makes sense. For what purpose would the separate masking

and treatment of the 4 hooks and the wood base serve (as is clearly

indicated in his "working print") other than as a matrix for

creating a composite image?

Related to evidence

of photo compositing, as found within Duchamp's "working print"

of the coatrack, is a curious 2nd version of a photograph of Duchamp's

Fountain urinal taken by stieglitz in 1917, and shown in illustration

33A and B. William Camfield's 1989 book, a chronicle of the odd history

of Duchamp's Fountain urinal, presented this second stieglitz

photo for the first time after it quietly appeared within the archive

of Duchamp's main patrons, the Arensberg's, in the 1950's.

|

Click

each

image to enlarge

|

|

|

Illustration

33A.

|

|

Known

stieglitz version of Duchamp's Fountain urinal published

in

Blindman N. 2,1917

|

|

|

Illustration

33B.

|

|

Second

version of stieglitz's Fountain photo (1917) -- not publicly

known until 1989

|

Before discussing

the potential importance of this particular photograph, and its delayed

appearance for spectators, let us again examine, as we did with the

hatrack and coatrack, the consistent approach that Duchamp uses to present

his readymades -- as a series of snapshots over time -- now applied

to Duchamp's urinal.

As we discovered with his snow shovel, hatrack, coatrack, bicycle wheel

and stool, Duchamp's original 1917 urinal does not exist today. Historians

such as William Camfield and Michael Betancourt have documented the

contradictions and conflicting stories that leave us with effectively

no definitive evidence about the urinal's existence -- including any

potential witnesses of the object (the few testimonies that exist conflict);

who photographed it (stieglitz himself, who supposedly photographed

the urinal for the 1917 Blindman publication, only briefly mentions

the urinal in writing, and no negative or print was ever found in his

archive); or how it quickly the urinal vanished into thin air in 1917.

I will not go into the details here, for they are so well pursued and

documented by Camfield and Betancourt. All that we do have, as for Duchamp's

hatrack, coatrack, and other readymades, is a series of urinal representations

in 2D and 3D that we can put together in a set (as in step A of Duchamp's

mental operation). We can then examine each depiction as its own snapshot

or cut (as in Duchamp's step B, where we take separate observations

over time). Since the original 3D urinal is "lost" as a source

for collecting more information, we must depend upon our ability to

average among, and compare differences between, each urinal representation,

see illustrations 34A, B , C, D, E, F, G and H. The tally of our representations,

encompassing what we know of Duchamp's urinal, follows:

| 3 |

|

2D

photographs of 1917 original

(two by stieglitz and one by unknown photographer) |

| 2 |

|

3D

models

(one miniature and one full size) |

| 2 |

|

2D

prints

(one in 1941 Boîte, one 1964 etching) |

| 3 |

|

2D

Blueprints

(two side views, one plan view) |

|

Total cuts

|

| |

|

10

snapshots of the urinal

(eight 2D, two 3D)

|

|

click

each image to enlarge

Time Line of Readymade Series of Urinals -- As Seen by

Spectators

|

|

34A

|

34B

|

34C

|

34D

|

34E

|

34F

|

34G

|

34H

|

|

click

|

click

|

click

|

click

|

click

|

click

|

click

|

click

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1917

|

1941

|

1941

|

1960s

(made 1916-17

found in 1960s)

|

1964

|

1964

|

1964

|

1989

(found

1950s

published 1989)

|

|

|

2D

photo by stieglitz from Blindman #2 journal, 1917

|

3D

miniature

model

in

Boite-en

-valise

|

2D

print

made from

studio

photo in

Boite-en

valise

|

2D

photo, studio photo

|

2D

etching,

edition of 100

|

3D

pottery model Schwarz edition of 8,

second corrected version by Duchamp

|

2D

set of blueprints

(first 3D model,

based upon blueprints, lost)

|

2D

photo fragment published by William Camfield

(original dating not known)

|

|

Note: This time line excludes urinal versions that Duchamp

did not originate.

© 2000

Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris

|

|

As we discovered when

examining Duchampís hatrack and coatrack, the above set of urinal depictions

in 2D and 3D do not describe one consistent 3D urinal. For example,

our analysis of the studio photo 1916-17 (illustration 34D found in

the 1960's), the 1941 print (illustration 34C created from a 1916-17

photograph) and the 1st version of the stieglitz photograph

(illustration 34A published in the Blindman #2) reveals an inescapable

conclusion -- namely, that two different urinals were represented in

1917. Again, our key question involves casualty -- did Duchamp change

urinals literally or photographically? Evidence for both hypotheses

exists. Duchamp did make his original 3D miniature urinal model in 1940,

and he did commission others to manufacture the full edition of 300.

Surprisingly, after Duchamp authorized Schwarz to make editions of 14

of his "readymades," Schwarz failed, despite intensive search,

to find even one of the 14 mass produced objects close enough

to Duchampís originals in 2D or 3D to serve as prototypes for the editions.

Therefore, Schwarz had to organize the manufacture of all 14 editions

himself. Stranger still, no duplicate urinal has even been found in

any catalogue, including the literature from the very company that Duchamp

specifically named his source for his urinal -- the Mott company.

|