|

Rites of Passage:

s / he

|

click

to enlarge |

| |

|

Figure

30 |

|

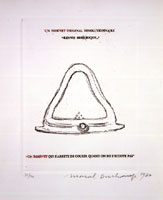

Marcel

Duchamp, Fountain, 1917

|

| |

|

Figure

31 |

|

Constantin

Brancusi, Princess X, 1916

|

Further elaborating

the domain of the "phallesse"--of such formidably phallic

she-males as "La Broyeuse de chocolat" and "Le Pendu Femelle"

/ "La Guêpe" (femelle)--Duchamp's Fountain (1917) (Fig. 30) analogously redesignates

and, in the process, exactly reverses what would very much appear to be

"un pissoir" (or, otherwise, "un urinoir"),

instead, as "une fontaine". Indeed, Kermit Champa asks,

"Phallic? Vaginal? It was a man-made female object for exclusive

male functions. Yet, who could characterize it precisely?"(43)

Nevertheless Fountain can perhaps be characterized as a "female object" in the

same sense that Duchamp might have described the similarly organic lines

of Brancusi's phallic totem, of only the prior year, Princess X

(1916) (Fig. 31). For Beatrice Wood, indeed,

Fountain was not only the "Madonna of the Bathroom",(44)

but also comparable to "a Brancusi, with curved lines of genuine

sensitivity",(45)

a formal logic perhaps informed by the fact that Fountain and

a version of Princess X were both slated to appear at the 1917

New York Independents exhibition.(46)

But Fountain is also a "female object" according to

another of Duchamp's randy quips: "On n'a que: pour femelle la pissotière

et on en vit" (DDS 37; cf. WMD 23). For those who easily

recall the days of disco, the gist is fairly clear--"I've got what

you want; you've got what I need":

| |

on n'a que = on a queue: we've got dicks

et on en vit = et on envie: and we want [what they've

got]

|

(Or, "where

there's pussy there's prick" ["où il y a Chaliapine"],(47)

as Duchamp elsewhere declares.) Lost in between what "we've got"

and what "we want", however, "pour femelle / la pissotière"

plays by an entirely different set of rules. Although I might as well

be quoting Freud's infamous remarks in his lecture on "Femininity",(48)

yet here too the problem--as in "Le Pendu Femelle" / "La

Guêpe" (femelle)--is "femelle". Like its closest English

translation--which is not really the "female" gender, but

rather the zoological "bitch"--"femelle" frankly

varies from catwalk to dogshow, for exactly which reason Flaubert counsels

its use "only in speaking of animals".(49)

No less problematical, however, is the second and likewise "femelle"

term: "la pissotière". Even so, "We've got dicks, but

all we've got for broads are open holes, and we want them"--taking

both "femelle" and "la pissotière" as crudely reductive

of male desire to the desire for any available opening--doesn't quite

work.

For, behind the

obviously problematic view of feminine sexuality inherent in "pour

femelle / la pissotière", the more fundamental problem is Duchamp's

intent to assimilate the meaningfulness of gender in its psycho-sexual

sense to its meaninglessness--or only circumscribed, even binary meaningfulness--in

any linguistic sense.(50)

By which I mean, why are farmers, pirates and poets all in the conventionally

feminine form in Latin, although grammatically they are masculine, and

in Rome they were paradigmatically men? This is the typically aesthetic

question to which Duchamp likewise reduces gender, most obviously, when

he explains to Cabanne, "If it isn't a literary movement, it's

a woman; it's the same thing".(51)

At this grammatical-as-ontological level, by simultaneously reversing

both the flow and the gender of "un pissoir", instead,

as "une fontaine", Duchamp similarly alienates it from

its expressly male identification by the simple and--like the rose of

Shakespeare and Stein--entirely arbitrary process of renaming it. So,

too, in "Le Pendu Femelle" ["the female of the species

which is male and hangs"], "La Guêpe" (femelle) and its

phallic stinger, as well as the Chocolate Grinderess and its

phallic cabriole "legs", even this process of renaming is,

itself, self-consciously marked and, in this sense, not unlike the use

of "she" as the indefinite personal pronoun, yet definitely

to raise the issue of why "he" is otherwise assumed. Duchamp's

early experience with the failure of English, by contrast, to gender

its articles might even explain the artist's otherwise inexplicable

preoccupation with no sooner arriving in New York than replacing each

occurrence of a gender indefinite "the" with an even more

indefinite "*" in his title text of 1915: The.

| click

to enlarge |

| |

| Figure

32 |

|

Marcel

Duchamp, Nine Malic Molds, 1914-15

|

Nevertheless, the

Nine Male-ish Molds (1914-15) (Fig. 32)--or

"Moules Mâliques [Mâlic (?)]" (DDS 76; WMD 51),

as Duchamp calls them--are perhaps the culminating example of all of this

grammatical-as-ontological play. Although both grammatically ["un

moule"] and descriptively ["mâlique"] masculine, their

vessel-like form is gender ambivalent: whether as uterine-like molds to

condense and cast gas (the enigmatic purpose Duchamp assigns them in the

Large Glass), or as dress forms whose typically male costumes

make (i.e. mold) the man. Yet, if "femelle" carries the double

signifying burden of "bitch", "mâle"--although obviously

the foil to "Le Pendu Femelle" / "La Guêpe" (femelle)

and "pour femelle / la pissotière"--carries no such double connotation.

As applied to the species, it means male; as applied to men, manly. Rather,

Duchamp descriptively emasculates the Molds, not as "mâle", but rather as "mâlique" or "mâlic"

(i.e. "male-ish") more as we might speak of clothes making the

drag king than the man. Like Rrose Sélavy--the "female-ish"

dress form, which is often confused with an alter ego (as if there were

any ego in any of this, in the first place)--the dress-form Molds

similarly identify the constructedness of language and of dress to that

of gender more generally. Indeed, if "mâlique" constitutes an

invented, feminine form of the adjective "mâle" (in the sense

that "-ique" tends to form the feminine), only further confusing

matters, "mâlic" restores Duchamp's neologism to an equally

invented, male-ish form (-"ic") --albeit one which is, itself,

derived from an invented, female-ish form (again, "-ique").(52)

Exactly confounding logic, then, we have "Le Pendu Femelle"

/ "La Guêpe" (femelle), which are clearly insertive, yet are

located in the upper register of the Large Glass: the so-called "Bride's Domain". On the other hand,

we have the Male-ish Molds which by definition are receptive, yet

are classed among the elements of its lower register: the so-called "Bachelor

Apparatus". With the phallic "Bride" on top, lording it

over her receptive "Bachelors" at bottom (cf. DDS 58;

WMD 39), feminine and masculine in their psycho-sexual no less

than their linguistic sense--rather than meaningfully contingent, historical

and political, coordinates--become meaninglessly binary axes, and these,

along an overarching grid of indifference.

Circles are straight. They are a straight line. --

"Joey" (53)

Becoming Full

Circle: From PiRr to πR2

Like the "circularity"

of the Bicycle Wheel, Coffee Mill and Chocolate Grinder -- or the tautological "I" they posit, whose

final determinant is only the "not-I" to which their onanism

opposes itself -- clad not only in the black leather of a Fresh

Widow, but also in "pi", the very figure of the circle,

Rrose Sélavy embodies an alternative (meta)physical trajectory. As Duchamp

describes her:

|

...en 6 pi

qu'habillarrose Sélavy

= [Fr]ancis

Picabia, Rrose Sélavy

= in sex,

[it is] "pi" that clothes eros, such is life(54)

|

| click

to enlarge |

| |

| Figure

33 |

|

Marcel

Duchamp, An Original Revolutionary Faucet: Mirrorical Return,

1964

|

In this sense, however,

revolution no longer describes a circular process of onanism, but rather

a rotational process of sexual involution--no longer a going around and

around, but rather a turning inside-out--as in Duchamp's engravings, Mirrorical Return (1964) (Fig. 33). Here, above

a line drawing of Fountain, the artist writes "an original

revolutionary faucet / 'mirrorical return'"; and below it, "a

faucet which stops running when we're not listening". In some sense,

the logic of a faucet "mirrorically returned" as a urinal is

only a variation on the circular theme with which we are already familiar.

Thus, the named, but not reproduced (effluent) faucet appears in Mirrorical

Return only by way of opposition to what it is not: the (influent)

urinal, which Duchamp does reproduce, as a line drawing of Fountain.

But Duchamp has also found a new binary axis--similar to "le"

/ "la", "mâle" / "femelle", etc.--with only

circumscribed (if any) meaningfulness, by means of which to reclassify

and once again to desublimate sexual identity as a sort of user's manual--"insert

tab A into slot B" --for them for whom neither hunger nor love moves

the world. Duchamp's new binary axis exactly continues his earlier play

on "mâle" / "femelle", now, as plumbing fixtures--or

"Lazy Hardware" as they are sometimes called (DDS 154;

WMD 106)--which are indeed classified as insertive ["tuyau

mâle"] or receptive ["tuyau femelle"], respectively.(55)

Neither is the "mirrorical return" Duchamp stages of "pour

femelle / la pissotière" at all unexpected: "pour mâle / le

robinet"!(56)

Yet what is "original

revolutionary", as the engravings boldly declare, either describes

a faucet caught in the pleonastic grip of advertising or one caught,

instead, in a "revolutionary"--in the sense of rotational--process,

which is itself "original": a sort of sexual spin-cycle, according

to which his sex goes in, her sex comes out; so too faucets go in, urinals

come out. Thus, rather than return Fountain to where it began--as

he does the "handle" of the Coffee Mill, completing its circuit of (de)tumescence--Duchamp brings Fountain

to where it never was, yet in some parallel sense always is. He rotates

it through the "fourth dimension", which exactly accounts

for its sexual involution, with what was an insertive / effluent faucet

"mirrorically returned" as a receptive / influent urinal.(57)

Indeed, that the faucet doesn't actually appear in Mirrorical Return

is precisely Duchamp's (fourth-dimensional) point. For urinal and faucet,

in this sense, are not analogous objects, but rather are alternate manifestations

of the self-same object. At any given time and place, only one aspect

of its essentially dyadic nature is in esse--the other aspect,

by contrast, is always in potentia, and awaits the object's rotation

through the fourth dimension. For this reason, Duchamp elsewhere compares

the process of "mirrorical return" to the effect achieved

by so-called "Wilson-Lincoln" diagrams (DDS 93; WMD

65). Seen from the left, these accordion-pleated diagrams appear to

be Wilson; only at another time and place--a few seconds later, say,

now seen from the right--do they appear to be Lincoln. In this way,

the object has no absolute priority of identity--whether Wilson or Lincoln,

faucet or urinal--but only a relative identity, a pure sexual (ex)change

value, whose coordinates need include not only a place (our three dimensions)

but also a time (the fourth dimension, according to popular understanding).

Although the "Wilson-Lincoln" diagram is destined to remain

among the Large Glass' definitively unfinished elements, yet

the only difference between it, a faucet "mirrorically returned"

as a urinal, and Duchamp's related researches into the fourth-dimensional

field of sexual involution--his 1950s erotic casts which we might never

more accurately describe as "invaginated"(58)--is

one of medium: e.g. Feuille de vigne femelle (1950) (Fig. 34), in

which her trough returns as a peak, if not strictly speaking his

peak; Coin de chasteté (1954) (Fig. 35),

in which a positive form and its negative are indissolubly elided; even

Objet-Dard (1951) (Fig. 36), in

which Eve's rib, from Etant Donnés, instead returns as Adam's (d)art.(59)

No differently than Duchamp reversibly genders sexual identity along

the axes of "le" / "la", "mâle" / "femelle",

he thus "engenders" the figure-ground problem: as a question

not only of three-dimensional versus invaginated / fourth-dimensional

space, but also of real versus virtual space, to which I myself now

turn. >>Next

|

click

on images to enlarge |

|

|

|

|

|

Figure

34

|

Figure

35 |

Figure

36

|

|

Marcel

Duchamp, Feuille de vigne femelle [Female Fig Leaf], 1950/61

|

Marcel

Duchamp, Coin de chasteté [Wedge of Chastity],

1954/63

|

Marcel

Duchamp, Objet-Dard [Dart-Object], 1951/1962

|

page

1 2 3

4 5 6

Notes

42. Bettelheim, The Empty Fortress, p. 241.

42. Bettelheim, The Empty Fortress, p. 241.

43. Kermit Champa,

"Charlie was like that", Artforum, vol. 12, no. 7

(March 1974): 58. Following Hopkins' analysis of Fountain in

terms of a proto-fetishistic / homosexual masculinity, Franklin anthropomorphizes

it, as turned on its side and photographed by Stieglitz, into a full-blown

Tea-Room Daddy -- and its "hollow, porcelain protrusion",

in particular, into a "bare, thick, round organ". See Paul

Franklin, "Object Choice: Marcel Duchamp's Fountain and

the Art of Queer Art History", Oxford Art Journal, vol.

23, no. 1 (2000): 26, 33. See also Hopkins, "De-Essentializing

Duchamp", p. 278; "Men Before the Mirror", p. 319.

Yet, by Franklin's own anti-essentialist logic, this "hollow,

porcelain protrusion" is a priori neither phallic nor

clitoral / vaginal, neither effluent nor influent.

43. Kermit Champa,

"Charlie was like that", Artforum, vol. 12, no. 7

(March 1974): 58. Following Hopkins' analysis of Fountain in

terms of a proto-fetishistic / homosexual masculinity, Franklin anthropomorphizes

it, as turned on its side and photographed by Stieglitz, into a full-blown

Tea-Room Daddy -- and its "hollow, porcelain protrusion",

in particular, into a "bare, thick, round organ". See Paul

Franklin, "Object Choice: Marcel Duchamp's Fountain and

the Art of Queer Art History", Oxford Art Journal, vol.

23, no. 1 (2000): 26, 33. See also Hopkins, "De-Essentializing

Duchamp", p. 278; "Men Before the Mirror", p. 319.

Yet, by Franklin's own anti-essentialist logic, this "hollow,

porcelain protrusion" is a priori neither phallic nor

clitoral / vaginal, neither effluent nor influent.

44. See William

Camfield, "Marcel Duchamp's Fountain: Its History and

Aesthetics in the Context of 1917", in Marcel Duchamp: Artist

of the Century, ed. Rudolf Kuenzli, Francis Naumann (Cambridge,

Mass.: M.I.T., 1990) 74, citing Beatrice Wood, I Shock Myself

(1985).

44. See William

Camfield, "Marcel Duchamp's Fountain: Its History and

Aesthetics in the Context of 1917", in Marcel Duchamp: Artist

of the Century, ed. Rudolf Kuenzli, Francis Naumann (Cambridge,

Mass.: M.I.T., 1990) 74, citing Beatrice Wood, I Shock Myself

(1985).

45. Beatrice Wood,

"Marcel", in Marcel Duchamp: Artist of the Century,

ed. Rudolf Kuenzli, Francis Naumann (Cambridge, Mass.: M.I.T., 1990)

14. In this sense, the Ready-mades indeed constitute a very specific

sort of object, one in which the immanence of form and function is

as atavistic, even, as the bodily functions to which they often refer.

For, however closely allied Duchamp's and Picabia's interest in mechanomorphic

imagery, when Duchamp undertakes the Ready-mades, he doesn't so much

shift gears as abandon them altogether. How very easy, for example,

to imagine Picabia's spark-plug girl -- Portrait d'une jeune fille

américaine dans l'état de nudité (1915) -- as part of the Large

Glass. How very difficult, by contrast, to imagine a real spark-plug

among the ostentatiously low-tech Ready-mades.

45. Beatrice Wood,

"Marcel", in Marcel Duchamp: Artist of the Century,

ed. Rudolf Kuenzli, Francis Naumann (Cambridge, Mass.: M.I.T., 1990)

14. In this sense, the Ready-mades indeed constitute a very specific

sort of object, one in which the immanence of form and function is

as atavistic, even, as the bodily functions to which they often refer.

For, however closely allied Duchamp's and Picabia's interest in mechanomorphic

imagery, when Duchamp undertakes the Ready-mades, he doesn't so much

shift gears as abandon them altogether. How very easy, for example,

to imagine Picabia's spark-plug girl -- Portrait d'une jeune fille

américaine dans l'état de nudité (1915) -- as part of the Large

Glass. How very difficult, by contrast, to imagine a real spark-plug

among the ostentatiously low-tech Ready-mades.

46. See William

Camfield, "Marcel Duchamp's Fountain: Aesthetic Object,

Icon, or Anti-Art?", in The Definitively Unfinished Marcel

Duchamp, ed. Thierry de Duve (Cambridge, Mass.: M.I.T., 1991)

152. Picabia's cover for the June 1917 issue of 391 -- depicting

a propeller, but entitled Ane [Ass] -- thus suggests that,

whatever the New York Independents choose to make of "Fontaine",

ultimately, "[ils se] Font Ane[s]" = "[they] Make Asses

[of themselves]," perhaps referring to "Buridan's Ass",

and the problems of choice and free will. Cf. Marcel Duchamp, Notes,

ed. and trans. Paul Matisse (Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou, 1980)

note 101. Picabia's propeller, moreover, captures not only the "circularity"

of the Ready-mades, but also their Brancusi-like resemblance to modern

sculpture. Cf. DDS 242; WMD 160, where Duchamp chastens

Brancusi: "Painting's washed up. Who'll do anything better than

that propeller? Tell me, can you do that?" See Ades, Cox, Hopkins,

Marcel Duchamp, p. 69.

46. See William

Camfield, "Marcel Duchamp's Fountain: Aesthetic Object,

Icon, or Anti-Art?", in The Definitively Unfinished Marcel

Duchamp, ed. Thierry de Duve (Cambridge, Mass.: M.I.T., 1991)

152. Picabia's cover for the June 1917 issue of 391 -- depicting

a propeller, but entitled Ane [Ass] -- thus suggests that,

whatever the New York Independents choose to make of "Fontaine",

ultimately, "[ils se] Font Ane[s]" = "[they] Make Asses

[of themselves]," perhaps referring to "Buridan's Ass",

and the problems of choice and free will. Cf. Marcel Duchamp, Notes,

ed. and trans. Paul Matisse (Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou, 1980)

note 101. Picabia's propeller, moreover, captures not only the "circularity"

of the Ready-mades, but also their Brancusi-like resemblance to modern

sculpture. Cf. DDS 242; WMD 160, where Duchamp chastens

Brancusi: "Painting's washed up. Who'll do anything better than

that propeller? Tell me, can you do that?" See Ades, Cox, Hopkins,

Marcel Duchamp, p. 69.

47. Duchamp, Notes,

note 265.

47. Duchamp, Notes,

note 265.

48. See Mary Anne

Doane, "Film and the Masquerade: Theorising the Female Spectator",

Screen, vol. 23, nos. 3-4 (Sept.-Oct. 1982): 74-77.

48. See Mary Anne

Doane, "Film and the Masquerade: Theorising the Female Spectator",

Screen, vol. 23, nos. 3-4 (Sept.-Oct. 1982): 74-77.

49. Gustave Flaubert,

Bouvard and Pécuchet with "The Dictionary of Received Ideas"

(1881), trans. Alban Krailsheimer, Robert Baldick (N.Y.: Penguin Books,

1976) 305. See also Jones, "Equivocal Masculinity", p. 204

(n. 82).

49. Gustave Flaubert,

Bouvard and Pécuchet with "The Dictionary of Received Ideas"

(1881), trans. Alban Krailsheimer, Robert Baldick (N.Y.: Penguin Books,

1976) 305. See also Jones, "Equivocal Masculinity", p. 204

(n. 82).

50. Cf. Spector,

Surrealist Art and Writing, p. 226 (n. 70), where he discusses

the French tendency to invest grammar with ontological significance;

Jean Clair, "Sexe et topologie", in Marcel Duchamp: abécédaire:

approches critiques, ed. Jean Clair (Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou,

1977) 59, where he describes Duchamp's works in terms of "a sort

of naive, ontological experience of mathematical ideality, where sexual

differentiation is abolished" (my translation).

50. Cf. Spector,

Surrealist Art and Writing, p. 226 (n. 70), where he discusses

the French tendency to invest grammar with ontological significance;

Jean Clair, "Sexe et topologie", in Marcel Duchamp: abécédaire:

approches critiques, ed. Jean Clair (Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou,

1977) 59, where he describes Duchamp's works in terms of "a sort

of naive, ontological experience of mathematical ideality, where sexual

differentiation is abolished" (my translation).

51. Duchamp, Cabanne, Dialogues

with Marcel Duchamp, p. 102.

51. Duchamp, Cabanne, Dialogues

with Marcel Duchamp, p. 102.

52. Robert Lubar

has pointed out to me that "une moule" [a mussel

(feminine)] is French argot for "cunt". Like a "clock"

which doubles as a female-ish / phallic "pendulum" ("Le

Pendu Femelle"), so too the Molds, then, are a sort of

male-ish "cunt".

52. Robert Lubar

has pointed out to me that "une moule" [a mussel

(feminine)] is French argot for "cunt". Like a "clock"

which doubles as a female-ish / phallic "pendulum" ("Le

Pendu Femelle"), so too the Molds, then, are a sort of

male-ish "cunt".

53. Bettelheim, The Empty Fortress, p. 254.

53. Bettelheim, The Empty Fortress, p. 254.

54. Amelia Jones,

Postmodernism and the En-gendering of Marcel Duchamp (N.Y.:

Cambridge University, 1994) 287 (n. 35). For variations on Duchamp's

pun, see DDS 151, 159; Duchamp, Cabanne, Dialogues with

Marcel Duchamp, p. 65.

54. Amelia Jones,

Postmodernism and the En-gendering of Marcel Duchamp (N.Y.:

Cambridge University, 1994) 287 (n. 35). For variations on Duchamp's

pun, see DDS 151, 159; Duchamp, Cabanne, Dialogues with

Marcel Duchamp, p. 65.

55. Cf. Craig

Adcock, "Duchamp's Eroticism: A Mathematical Analysis",

in Marcel Duchamp: Artist of the Century, ed. Rudolf Kuenzli,

Francis Naumann (Cambridge, Mass.: M.I.T., 1990) 153.

55. Cf. Craig

Adcock, "Duchamp's Eroticism: A Mathematical Analysis",

in Marcel Duchamp: Artist of the Century, ed. Rudolf Kuenzli,

Francis Naumann (Cambridge, Mass.: M.I.T., 1990) 153.

56. On the

"erotic homology between a spigot and a penis", see Franklin,

"Object Choice", p. 47 (n. 114).

56. On the

"erotic homology between a spigot and a penis", see Franklin,

"Object Choice", p. 47 (n. 114).

57. In sum, a

round-trip ticket to the fourth dimension buys the ticket-holder a

doubly inside-out and left-right reversed welcome home. See Adcock,

"Duchamp's Eroticism", p. 149. Although unobservable in

the case of bilaterally symmetric plumbing fixtures, the potential

for left-right reversal exactly accounts for the Tu m' corkscrew

(on which, see n. 69, herein). On the eroticism of Duchamp's fourth-dimensional

imagery, see Adcock, "Duchamp's Eroticism", pp. 149-67.

On Duchamp's fourth-dimensional imagery more generally, see Craig

Adcock, "Geometrical Complication in the Art of Marcel Duchamp",

Arts Magazine, vol. 58, no. 5 (Jan. 1984): 105-9; Linda Henderson,

The Fourth Dimension and Non-Euclidian Geometry in Modern Art

(Princeton, NJ: Princeton University, 1983) 117 ff.

57. In sum, a

round-trip ticket to the fourth dimension buys the ticket-holder a

doubly inside-out and left-right reversed welcome home. See Adcock,

"Duchamp's Eroticism", p. 149. Although unobservable in

the case of bilaterally symmetric plumbing fixtures, the potential

for left-right reversal exactly accounts for the Tu m' corkscrew

(on which, see n. 69, herein). On the eroticism of Duchamp's fourth-dimensional

imagery, see Adcock, "Duchamp's Eroticism", pp. 149-67.

On Duchamp's fourth-dimensional imagery more generally, see Craig

Adcock, "Geometrical Complication in the Art of Marcel Duchamp",

Arts Magazine, vol. 58, no. 5 (Jan. 1984): 105-9; Linda Henderson,

The Fourth Dimension and Non-Euclidian Geometry in Modern Art

(Princeton, NJ: Princeton University, 1983) 117 ff.

58. In medical

jargon, the difference is exactly between her "invaginated"

sex and his "external" one, which Duchamp identifies to

the fourth-dimensional process of sexual-as-spatial involution more

generally. Indeed, in Duchamp's fourth-dimensional imagery, "vagina

and penis lose... all distinctive character". Clair, "Sexe

et topologie", p. 58 (my translation). See also Dalia Judovitz,

Unpacking Duchamp: Art in Transit (Berkeley: University of

California, 1995) 212-19; Hellmut Wohl, "Duchamp's Etchings of

the Large Glass and The Lovers", in Marcel Duchamp:

Artist of the Century, ed. Rudolf Kuenzli, Francis Naumann (Cambridge,

Mass.: M.I.T., 1990) 180. Cf. Jones, Postmodernism and the En-gendering

of Marcel Duchamp, p. 91, citing Ecke Bonk, Marcel Duchamp:

The Box in a Valise (1989).

58. In medical

jargon, the difference is exactly between her "invaginated"

sex and his "external" one, which Duchamp identifies to

the fourth-dimensional process of sexual-as-spatial involution more

generally. Indeed, in Duchamp's fourth-dimensional imagery, "vagina

and penis lose... all distinctive character". Clair, "Sexe

et topologie", p. 58 (my translation). See also Dalia Judovitz,

Unpacking Duchamp: Art in Transit (Berkeley: University of

California, 1995) 212-19; Hellmut Wohl, "Duchamp's Etchings of

the Large Glass and The Lovers", in Marcel Duchamp:

Artist of the Century, ed. Rudolf Kuenzli, Francis Naumann (Cambridge,

Mass.: M.I.T., 1990) 180. Cf. Jones, Postmodernism and the En-gendering

of Marcel Duchamp, p. 91, citing Ecke Bonk, Marcel Duchamp:

The Box in a Valise (1989).

59. On the biblical

referent of the rib imagery, see Adcock, "Duchamp's Eroticism",

p. 162, citing Francis Naumann. In an especially felicitous turn on

the "mâlic" molds, Clair would conversely describe Duchamp's

erotic casts as "femâlic". Clair, "Sexe et topologie",

p. 56.

59. On the biblical

referent of the rib imagery, see Adcock, "Duchamp's Eroticism",

p. 162, citing Francis Naumann. In an especially felicitous turn on

the "mâlic" molds, Clair would conversely describe Duchamp's

erotic casts as "femâlic". Clair, "Sexe et topologie",

p. 56.

Figs.

30, 32-36

©2003 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

All rights reserved.

|