Fountain

|

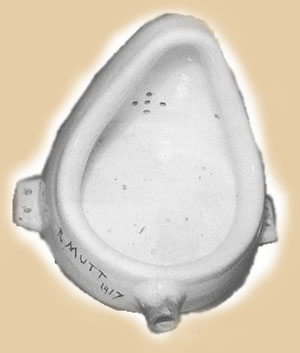

Original Version:

1917, New York |

|

| Original version, Alfred Stieglitz photo, 1917 |

A urinal displaced and called art, this Readymade has caused much controversy ever since the fateful day in 1917 when it was refused entry to an art show priding itself as being open to all. Rotated and signed with the pseudonym "R. Mutt 1917" on its upper side, Fountain isn't merely one of Duchamp's Readymades. It has become a recognizable icon in the history of modern art.

Overtly displaced from its original context (the everyday bathroom), Fountain is not only rotated, but has been displayed suspending from a doorjamb (Molesworth 56). In fact, this Readymade was hung from a lintel at an exhibition in the Sidney Janis Gallery in New York in 1953 (Ramirez 58). Molesworth notes the complete uselessness of the urinal in such positions, humorously noting that, "if a man pees in the Fountain his urine will drip on him (56).

|

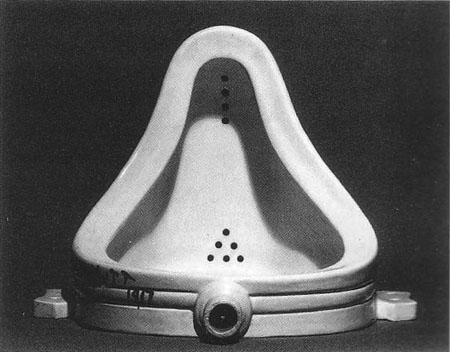

| Replica, 1950 |

Fountain is perhaps best known for the huge historical scandal it sparked in the art world: the Richard Mutt Case. It was refused entry to the first exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists at the Grand Central Palace in April 1917. A huge commotion followed over the Fountain not being decent. The following excerpt, originally published in the Blind Man (a Dadaist publication), was signed with Duchamp's pseudonym "R. Mutt" :

The Richard Mutt Case:

They say any artist who pays six dollars may exhibit.

Mr. Richard Mutt sent in a fountain. Without discussion, this object disappeared and was never exhibited.

What were the grounds for refusing Mr Mutt's fountain:-

1. Some contended it was immoral, vulgar.

2. Others that is was plagiarism, a plain piece of plumbing.

Now Mr Mutt's fountain is not immoral, that is absurd, no more than a bathtub is absurd. It is a fixture which you see every day in plumbers' show windows.

Whether Mr Mutt made the fountain with his own hands or not has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view - created a new thought for that object.

As for plumbing, that is absurd. The only works of art America has produced are her plumbing and her bridges.

(Ramirez 54)

|

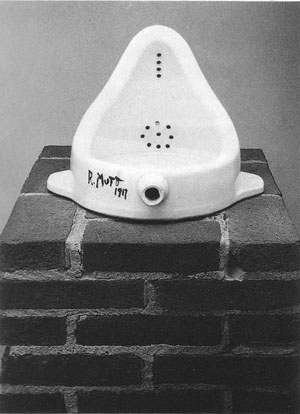

| Replica, 1964 |

Ramirez explores why this piece may have been so controversial. One of the basic criterion for a Readymade states that it is inherently neutral and chosen with no aesthetic thought. However, "a urinal elevated to the level of a work of art cannot, under any circumstances, be considered as something 'neutral'" (Ramirez 54). Ramirez also offers a highly sexual interpretation of the piece. Because it embodies characteristics of both sexes, he argues that the urinal is neither masculine nor feminine, but "bisexual" (56). Despite its obvious male connections, it also has feminine aspects; it acts as "a receptacle for liquid effusions of different kinds: showers, natural waterfalls, perfumes, etc" (Ramirez 59). Others also support this gendered bisexual interpretation. Greben notes the bisexual nature of Fountain when she writes that Duchamp "wittily positioned the phallic receptacle on its side to suggest female genitalia." She further sites independent curator Debra Bricker Balken as explaining that "[Duchamp] aimed to scramble, confuse gender..." (105).

|

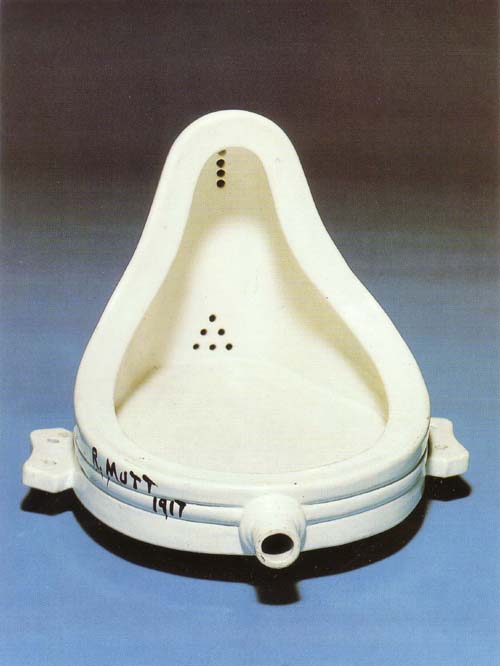

| Replica, 1963 |

The response to this Readymade was heated at the time it was made public nearly ninety years ago and still continues to annoy viewers to this day. Judovitz explains that Fountain "flushed the notion of artistic value down the drain" (160). As visual arts editor Dave Gagon related in a Salt Lake City newspaper in March 2003, "While I find 'Fountain' amusing and at least historically significant, many museum visitors were truly 'bewildered.'" The editor presents some of the comments he heard at an exhibition, including: "'What the... it's a stupid toilet'; 'You've got to be kidding'; 'Hah!'; 'They can't be serious'" (1).

Why Duchamp chose to sign this piece with the name "R. Mutt" is a question scholars have been throwing around for years. Originally Duchamp claimed that the "Mutt" came from the character Mutt in the then popular Mutt and Jeff comic strip, as well as from J. L. Mott Ironworks, the company brand name of the type of urinal he claimed his Fountain was. However, one must realize that Duchamp isn't always straightforward and may have been pulling the viewer's leg with this explanation... or maybe not. Either way, Varnedoe argues that (contrary to what most say) Fountain is not actually a J.L. Mott Ironworks urinal at all, which are considered the "cadillacs" of the bathroom trade. He contests that the piece Duchamp claims to be this high-class model is in fact a very "low-class" urinal, a porcelain "flatback Bedfordshire urinal with lip" (274). Apparently the only "lower" type was that used in prisons (274).

Other theories have also arisen to account for the term "Mutt" in the strange pseudonym "R. Mutt." Sewell notes that "Mutt" is American slang for a "fool" or "gawk," and that therefore perhaps such a title was included in order to "challenge everyone who saw his preposterous metamorphosis of the urinal" (17). Sewell reminds us in this context that Duchamp "was very much a man for puns and phonetic jokes" (17). Meanwhile, Hopkins supports a rather complex psychoanalytic and Freudian interpretation of the "Mutt" pseudonym, essentially leading to a bisexual personification of the Fountain. He notes that Freud linked "Mut" (the name of a hermaphroditic Egyptian goddess) with the German word for mother ('Mutter'). If this term is phonetically reversed in French, "it is easy enough to end up with R. Mutt, (and it should be added that Duchamp was later to carry out a literal reversal of "Mut" in the title of his 1918 painting, T um')" (305-6).

Today, the original version of Fountain has long been lost. "All that remains are the replicas made by Sidney Janis in 1950, by Ulf Linde in 1963, and by Arturo Schwartz in 1964, and also, of course, the photograph taken by Alfred Stieglitz in 1917" (Duve 95-6). Loesberg notes that, "...despite Duchamp's participation in some of the re-creations, no one exactly resembles another (although all are signed on the left rim by R. Mutt and dated 1917 as if the signature rather than the exact features of the urinal testify to the authority of the artwork)" (55). On the same note, one must realize that, on a certain level, "only after [Fountain] ceased to exist as an object did it become an uncontested artwork" (Loesberg 55). However one approaches the situation of the replicas, it is undeniable that the controversy surrounding the Fountain has hardly faltered. Just the idea of this urinal existing as "art" in a traditional museum setting is enough to anger and confuse people to this day.

Replicas:

1) 1950, New York

Private Collection

30.4 x 38.2 x 45.9 cm

Selected by Sidney Janis in Paris at request of Duchamp for exhibition in NY, 1950

2) 1953, Paris

Selected for sale at auction to benefit a friend of Duchamp

|

| Replica, 1964 |

Moderna Museet, Stockholm

Gift of the Moderna Museets Vanner

33 x 42 x 52 cm

Selected by Ulf Linde for Duchamp retrospective, Stockholm, 1963

Inscribed on upper side (in block letters, not artist's handwriting): "R. Mutt / 1917"

Inscribed by artist in 1964

4) October 1964, Milan

Edition of eight, each 36 x 48 x 61 cm

Under artist's supervision from Stieglitz photo of original

Inscribed exterior top rim, in black paint, "Marcel Duchamp 1964"

On back rim: "R. MUTT / 1917"

Small copper plate to back: "Marcel Duchamp 1964 1/8-8/8", "FOUNTAIN / 1917 / EDITION GALERIE SCHWARZ, MILAN"

2 replicas to artist and publisher, 2 more for museum exhibition