|

page10

|

|

Why

the Hatrack is and/or is not Readymade: by Rhonda Roland Shearer with Gregory Alvarez, Robert Slawinski, Vittorio Marchi and text box by Stephen Jay Gould

<PART III> |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Duchampís

Revolutionary Alternative

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Stereo

viewers were all the rage in the late 19th, early 20th century

Click each image to enlarge |

||

|

Illustration

52A.

|

Illustration

52B.

Saugrin Album Magique |

Illustration 52C.

|

|

Stereo

viewers were used for entertainment and education around the world.

|

French

made Stereo-Viewer and

book with cards in one gadget. |

Hundreds

of different Stereoviewers

were patented throughout the world; many types are here on this book cover. Paul Wing, Stereoscopes, The First One Hundred Years, 1996 |

|

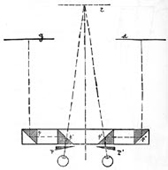

Illustration 52D.

Stereo effect created with Prisms |

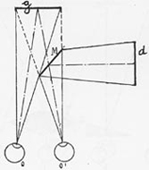

Illustration

52E.

90ļ Mirror system creates stereo effect |

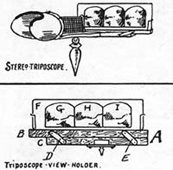

Illustration

52F.

|

|

Various

prism and mirror systems were tried to stretch and test the limits

of what was possibile in creating stereovision.

|

This

unusual optical devise uses three images instead of two!

|

|

The limitations of human perception and cognition lie at the center of our illusionary experiences evoked by 3D stereo vision or even by "moving pictures," where projections of film, when speeding by fast enough, appear continuous because our eyes and minds are, literally, too weak to detect separations between the 2D images. Moreover, it requires no great leap, for someone as intelligent as Duchamp, to understand that these 19th century optical experiments expose not only this retinal weakness, but (and more importantly) also suggest, in general, how perception and cognition work. We learn that our eyes and minds take bits of information (from the past and present) and seamlessly fuse them together. However, what we actually think we see, unless we become directly analytical and override this automaticity, is much more dominated by a mental construction than we consciously realize.

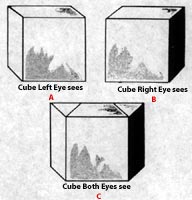

For example, when

we view a depiction

of a cube, we are essentially guessing that this object is a cube, based

upon both the direct information that we have in illustration 53 and

upon prior experience. The idealized construction of

"cubeness" in our minds completely erases the additional information

of the cube that

our two eyes literally see. In illustrations 54A,B, and C, two

views of the same cube are separately represented as seen by the left

and right eyes (54A,B), whereas 54C is the amount of information that

both eyes actually see. Illustration 54D shows a schematic plan (in

birdís eye view) of two eyesí field of vision and fusion when looking

at a cube.

We obviously see more

information with stereovisionís two eyes than in photography and perspectiveís

"one-eyed vision." The mindís action of fusing two 2D images

into a single 3D experience has also raised the dimension of our perception

and, therefore, also increases the information available to our senses,

as shown in illustration 54C. Not everyone possesses the ability to

see representations in stereo. Severe astigmatism, or blindness in one

eye makes the 3D fusion of two 2D images impossible. In early books

on stereo vision, 19th century experiments that tested the

possibility of an optical device that would allow a single 2D image

to be seen as 3D with only one eye were cited and ridiculed as obviously

fated to fail. The research of Stephen Jay Gould and me reveals that

Duchamp himself was the first person, even before any scientist succeeded,

to develop a system and a device (1923) that produced a 3D stereo fusion

in the mind with a single 2D image seen by a single eye. Try the Interactive

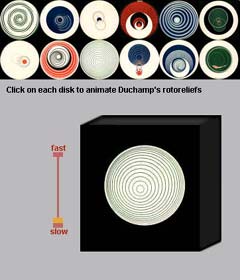

Presentation in illustration 55. Duchampís Rotorelief Discs (1935)

surprisingly produce an even greater 3D effect when seen by one eye

than by two. Click on any disc to select. Control speed by clicking

on bar and dragging bar up and down (with depressed clicks) between

fast and slow. Duchamp first made his Rotorelief Discs

for phonographic record playing speeds, 78 or 33 3/1.

| Click here for Interactive Presentation |

|

Illustration

55.

|

|

Duchamp's

Rotorelief Discs (1935)

(machine modeled after 1964 version created by Vittorio Marchi and Robert Slawinski) |

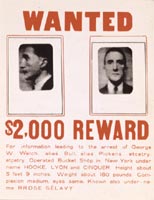

Duchamp created many other experiments using stereoscopic pairs. He included two examples in his Boîte-en-Valise miniature museum (Figs. 56A and 56B). These two stereoimages were made by Duchamp in 1918 and 1920 but not published until 1941. As I discussed at the Harvard symposium Methods of Understanding in Art and Science: The Case of Duchamp and Poincaré, Duchampís previously unrecognized stereo experiments, as detected by my studies, include one work, the Wanted Poster (1921), that was (since 1941) viewed as a "readymade" object that Duchamp only altered by personalizing the object with photos and text referring to himself. (See illustration 57A and 57B, the Wanted Poster print, first seen by spectators in the Boite-en-Valise (1941), as the original Wanted Poster (1921) work is "lost."

|

Click

each image to enlarge

|

|

Illustration

57A.

|

|

Duchamp

Wanted Poster (1921) printed in 1941 Boite-en-valise

|

|

Illustration

57B.

|

|

Wanted

Poster detail, Duchamp's underground stereo experiment can be

seen when this detail is placed into a stereo viewer.

|

I noted that the red and blue colored boxes and the two portrait photos (of what may be, even in Duchampís original photo source used to recreate his work, a retouched composite of Duchamp and someone else -- a criminal perhaps?) are asymmetrically placed and shaped. In other words, the left Duchamp image is higher than the right image, and the lines of the boxes themselves are strangely designed to be uneven. I noticed one day that both the size and the separation between the 2 boxes seemed similar to a common stereo card. I scanned, printed and then cut off the top of the Wanted Poster at a duplicate size in the Boîte-en-Valise folder (56B) and then placed it in to a stereo viewer. When seen in stereo, the two asymmetrically shaped boxes in the Wanted Poster unexpectedly fuse into one symmetrical box. I now could see a single Wanted Poster image of Duchampís

|

click

to enlarge

|

|

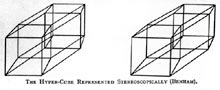

Illustration

58.

|

|

The

Hyper-Cube represented stereoscopically (Benham)

|

|

Click each image to enlarge |

|

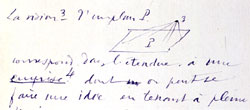

Illustration

59.

|

|

English

translation of the Note: "The View3 of a plane P.

corresponds in the hyperspace to a grasp4 of which one can get an idea by gripping a penknife in the hand, for example" Marcel Duchamp, mathematical note from In the Infinitive [a.k.a. the White Box], written in 1910s published in 1967 |

|

Illustration

60.

|

|

Cover

design done by Duchamp for his Catalogue Raisonnť (1953) includes

this portrait photograph that illustrates the similar "4D"

effect (seeing front and side view at once) found when placing

the Wanted Poster (57B) into a stereo viewer.

|

Using what Duchamp called a 4D eye [eye4], only 4D space allows us to see 3D objects 360į in the round in one instant; whereas, in 3D space a 3D eye (eye3) must move in time around a 3D object to collect 2D observations (thus reducing an object from 3D to a series if 2D shapshots). Only after these cuts are fused together, can we recreate in our minds a sense or approximation of any actual 3D object in the round (thus increasing the dimension when transforming a series of 2D cuts into a 3D object). Duchampís note, illustration 59, uses the fistís ability to hold and experience the form of a 3D object, all at once, as analogous to what would occur in 4D vision. Illustration 60, a portrait photograph of Duchamp, also mimics what could only be simultaneously seen in 4D space. This portrait is also similar to the experience evoked when seeing the two Wanted Poster heads and lined boxes in a stereo viewer. Significantly, Duchamp selected this very photo (60) as the cover for his own catalogue raisonné design in 1958.

With Duchampís underground experiment in the Wanted Poster, we may have increased our information with a 4D experience, but the data provided by Duchampís head are still incomplete. Panoramic painting and photography represented yet another 19th and 20th century experiment and approach to packing even more 3D information into 2D images. Illustration 61 shows a "panoramic" view of a womanís head. The photo uncomfortably reads as if a 360į view of the womanís head were rolled out, like cookie dough, onto a 2D plane. Such a panoramic photograph, by allowing us to see a 3D object (such as a head) on all sides at once, certainly yields more 3D information in

|

click

to enlarge

|

|

Illustration

61.

|

|

A

panoramic photo of a woman's head captures a whole 3D object in

2D space, allowing it to be seen all at once.

|

|

click

to enlarge

|

|

|

Illustration

62.

|

|

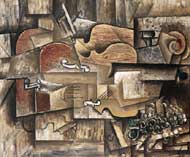

Pablo

Picasso, Violin and Grapes, spring and autumn, 1912

|

Cubism, in addition to its status as the beginning of one of the two biggest revolutionary departures in art (the other being the advent of perspective itself in the Renaissance), emerged, for Duchamp and others, as yet another experiment and alternative to static perspective representation in the larger cultural context of the early 20th century (see illustration 61, a cubist painting by Picasso).

* Article Part IV through VI will be published in Tout-Fait, Perpetual 2004.