"A very normal guy" Robert

Barnes on Marcel Duchamp and Étant Donnés

Tout-Fait:

Well as you can see in the Manual of Instructions (Figs.

4, 5, 6) here, you can disassemble it in certain

points. But when you say it was all over the place, what do you mean

by that?

Robert Barnes:

There were pieces of it. It was not hard to see what it was. I don't

remember the branches.

The thing I remember most about all this is the damn floor. Well it's

so appropriate and so ugly and the building was so awful, but that

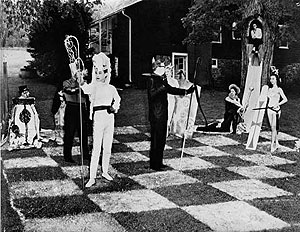

floor, made sense. There's that movie of Richter's

(3), 8x8

(Fig. 7), with a giant chessboard

and people walking on it. And I always thought that you almost needed

to hop in that studio the way you hop from one square to another.

Tout-Fait: Judging from the preliminary works (Figs. 8, 9), some argue that he first tried to construct Étant Donnés as a standing figure, was it always lying there? Robert Barnes: Yeah. I don't think it ever could stand and I don't think he cared or wanted it to. He might have wanted to position it up a little bit so you had to look at the pudenda. Tout-Fait: You can say pussy if you like. Robert Barnes: I know you can say pussy but I don't know… Tout-Fait: What do you think in terms of this thing being anatomically correct, do you think he took life casts? Robert Barnes: No, he didn't give a damn about whether it was anatomically correct. In some ways--I mean if you look at it as he intended, as a voyeur, somebody peeping through a hole--it is shocking because the pussy is not right and you look at it and you say, "oh wait, no this isn't right" and you start adjusting. Marcel was smart enough to make you think that and also being hairless it was a little bit like kiddy-porn.

Tout-Fait: But what you said with the spectator or the voyeur, looking at this and seeing, you know you have Courbet's Origin of the World (Fig.10) and there you have an anatomically more or less correct pussy (4), whereas Duchamp's intentionally wasn't right? Robert Barnes: Well with Courbet, you know what you're into, if I may pun a bit. In Duchamp you approach it with doubt, you're not sure you want to be there or should be there, want to be there is maybe even more important. With Courbet you know what you're thinking about, this is obviously a woman… With Duchamp you have the inaccuracies and the fact that the body is not right at all. The whole wig thing. It's all wrong but you look at it and start rearranging it and of course everything he did was like that and the attempts to explain Duchamp I think are terrible because it is alien to the point. And I think even Duchamp's explanations, all the things he wrote, were misleading. I think intentionally misleading, done after the fact, and meant to feed people who want to be fed. Tout-Fait: Why would you think he intentionally constructed a torso that you notice is not a torso but rather some distorted figure. Why would he not try--if he uses all of these 3-D materials--why would he not try to aim for an anatomically correct torso? Robert Barnes: Because he wasn't an academician. If he wanted to make it anatomically correct he could have done that and it would not have had the same impact. Tout-Fait: Because none of the men I know that are into women and look at this thing find it sexually arousing. Robert Barnes: Oh, I do. Tout-Fait: Oh you do? Robert Barnes: I think it's neat. The thought that you have is you sort of wish that women were built like that, were made like that, a little distorted, a little extra. But I'll get off that subject quickly before I get arrested. I was always amazed at how many people were embarrassed by it and obviously that was the intent of the work. I mean all of these nitwits that looked at it and said it's not worthy of Duchamp were the ones that he was out to get. And I loved it. You know I didn't see it. I never saw it put together until much later. Tout-Fait: But you saw it. The thing is though, when it was reviewed, when it was released to the public in 1969 at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, John Canaday of the New York Times already wrote at the time that Étant Donnés was "very interesting, but nothing new," maintaining that in the light of artists like Edward Kienholz, Duchamp, "this cleverest of 20th century masters looks a bit retardaire." In other words, it looked dated and surely wasn't shocking anymore. Robert Barnes: Because Duchamp was before and fed into this age that had to be shocked. Étant Donnés is not shocking, it's embarrassing. Big difference. You look at it and you think "I should not be thinking this or looking." And you're not shocked but I mean no one can approach this piece of work without it clobbering him. And Marcel was very subtle. Tout-Fait: He was very subtle. What do you think about him working with such a different media, all of the sudden coming up with this three-dimensional environment? Robert Barnes: Why is it so different? He made the thing. His other casts of women are all leading up to this… Tout-Fait: Well that is one thing. When he did the casts… Robert Barnes: I never asked who it was. I suppose it was Teeny. Tout-Fait: There are different stories about the casts. Robert Barnes: I guess you'll have to find the "castee" or "castette."

Tout-Fait: Take the Female Fig Leaf (Fig. 11), for example. Richard Hamilton says that Duchamp told him he did these things by hand, whereas Duchamp scholars like Francis M. Naumann think that he actually took a live cast. Robert Barnes: Oh, well he would have taken a live cast because it's more fun. Tout-Fait: But who would that have been? Maria Martins (5) or Teeny or both? Robert Barnes: Probably anybody--anybody who would lend her body. Tout-Fait: You know Duchamp toyed with the fourth dimension in the Large Glass. Do you think there might also be something of that in the distorted body, by arriving--as Rhonda Roland Shearer has argued--at a higher level of representation because it is not just 3-D. But by rendering a body, somehow through distortion, thus incorporating movement in time--or do you think this is going too far?

Robert Barnes: Well if he had done it merely in 3-D, it would have been a George Segal (Fig. 12,13). He wasn't interested in that, he's better than that. I don't know if you've noticed it. But Duchamp was magnificent. He was so smart, so intelligent, his brain was so complex and that's the best thing about him that I don't think anyone… I think you can only approach appreciation to Duchamp and I don't think his intelligence was where people thought it was. Everyone felt that Duchamp was 'scientifically pure, he could think in mathematical ways.' I don't think he could add beans. I think Marcel was inventive because he was beyond science; he was beyond accuracy and Figures. He was beyond all that because then he could approach us; he could manipulate us. Being around Duchamp was always--I wouldn't say challenging because he made people comfortable--but the thinking was rapid and he wasn't the only one, Matta was quick, too. All of those people in the circle of Duchamp were quick. Tout-Fait: And you were young and in their midst. Robert Barnes: I was just a baby. I was a pretty kid. I didn't ever approach them with enough reverence though. I felt like I just was interested. It wasn't "oh the big artist." Because it is like anything, if you know a celebrity, you are always shocked at how human they are. The first time I met Duchamp, I went with Matta, and Duchamp had a cold and the first thing I thought, "men of this stature don't get colds." And he was in his bathrobe eating honey out of a silver bee. Now if that wasn't so much Duchampian as Ernstian or something Richter would have thought of. But it was weird because it was so appropriate and his apartment was always a place where… I wonder where all that stuff is, do you know? Tout-Fait: I don't know exactly, it went to the estate I guess. Robert Barnes: But who was left in the estate after Teeny? Tout-Fait: I believe Teeny's three kids, Jacqueline Matisse Monnier as well as Paul and Peter Matisse. Robert Barnes: What did they do with all of that? Tout-Fait: Some of it was donated to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, other works were donated to the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris. Robert Barnes: Can you imagine… you know he used to have an armchair that was done in needlepoint by Miró (6)? It was all so oily because he would always lean on it. It was his favorite chair. Could you imagine sending that to the Salvation Army? Tout-Fait: Was it? Robert Barnes: I don't know. Every time when someone dies they give stuff to the Salvation Army. That reminds me of a gathering at Duchamp’s place once. All the people were staring at me. It was very uncomfortable. I don't like being stared at. And Duchamp who was so sensitive, he knew that I was feeling uncomfortable. And he leaned over and he said to me "They are looking at you Robert, because you are sitting on a Brancusi" (7)--a little bench thing--and I started to get up and he pushed me down and said. "That's what it's for, to be sat upon. So let them look at the Brancusi and forget about yourself." And I did. Tout-Fait: Can you recall how many parts Étant Donnés was? How many parts when you saw it there at his place? Robert Barnes: No, the best thing I can remember about the place was the chess-board floor. I mean that's very exciting, isn't it, for history. Tout-Fait: So the only time you helped him with it, was getting the pigskin? And how many times had you been to the secret studio on 210 W 14th Street? Robert Barnes: Oh, lots of times. I lived just down below there for a while. Tout-Fait: So you saw the progress that was made? Robert Barnes: Yeah. And at the time I was working for Carmen DiSappio who was just down the street, so… Tout-Fait: So when works like Female Fig Leaf came out and those things that had to do with Étant Donnés that people could only place it with Étant Donnés later because they did not know about it. When you saw these pieces you already knew that they had to do with this kind of work? Robert Barnes: The thing is that if you knew Marcel and you knew the people around them, this is a sequence that is so practical and natural, I mean these were horny people my friend. Matta was probably the horniest of all. He's probably still trying to dick everything in sight. These were people who thought about sex. I mean, it's all about sex--the gas. That's what bothered me about Étant Donnés, what kind of light bulb is in the lamp? Tout-Fait: It's an electric light, though it's supposed to be a Bec Auer, a gas burner. Robert Barnes: Those long things?

Tout-Fait: Yeah the long thing, that has a green light emanating from it, under which Duchamp experimented when he did the Chess Players in 1911 (Fig. 14). He painted in that green light. So although with Étant Donnés it is an electric lamp, it is supposed to be a gas lamp. Robert Barnes: So that is maybe where the gas came in. The gas is like what we lately have discovered as pheromones, I think, which is a sort of sex gas. Tout-Fait: What is sex gas? Robert Barnes: Gas! And with Marcel, gas is always sex gas; it will get you. Worse than mustard gas, you're done for. Tout-Fait: Well, after all Étant Donnés' subtitle is 1) The Waterfall / 2) The Illuminating Gas. Do you recall having seen the painted landscape with moving waterfall used as the artwork's backdrop? Robert Barnes: No. I think the scene was there but I don't remember anything happening back there; it was dark. I'm embarrassed to say it, but I didn't focus on much of it then. Tout-Fait: But you and Duchamp saw each other often? He was at your apartment and he liked the way it was built. What's the story about that? Robert Barnes: Yeah, I lived on Kenmare Street. It's an architectural museum now or something. It is right across the street from the Broome Street police station. Downstairs was a tire store and there were these troll-like men who repaired tires down there and they had these vats where they would test to see if they were leaking. It was something right out of an opera by Wagner except that the blacksmiths were vulcanizers, which is perfect. And upstairs I had my loft, which was illegal, and Marcel loved it because it was. It had a door like Étant Donnés, a shackled door, and the little place was a mess but I had put in plumbing and we would all go down to Hester Street and buy plumbing supplies. We all got glass-lined water heaters that rusted but one of the joys of the place was that we couldn't put an elbow in the tub, so it went straight. And we discovered that when you let the water out of the tub, it would explode downstairs in the tire tub. It was kind of Duchampian. Tout-Fait: But he came by and visited you? Robert Barnes: Yeah, not very often. Tout-Fait: You were there in the early ‘50s and you stayed in New York for how long? You were already married by then and you lived with your wife who was probably young and beautiful at the same time. So were the artists that you knew fond of her as well? Robert Barnes: Yeah, Matta was. He wanted to steal her. Tout-Fait: But Duchamp wasn't hitting on her? Robert Barnes: I wouldn't have known if he was. She would have, but I wouldn't have. Actually my wife was, at the time, beginning to show some symptoms of mental problems, so she didn't go places. Her contact was rather limited. Tout-Fait: So, you were there at the time when fame started setting in for Duchamp. There were more and more people approaching him. In this regard you mentioned something about "Mr. Availability." Robert Barnes: I think that was Teeny's term. He was interested, I think, that was it. I don't know why anyone paid attention to me because I was really wet behind the ears. He was awfully nice to me and listened to me and I don't think I had much to say. Tout-Fait: But they liked to have you around. Robert Barnes: Yeah, I think I was decorative and I think they thought of me as maybe being someone to follow. Not follow, no, there was never any hint that I would follow anybody. Tout-Fait: Well you were doing figurative oil on canvas and Duchamp, probably the others too, appreciated what you were doing since everyone else had stopped doing that. You said Duchamp liked the painting that was at the Whitney, your Judith and Holofernes of 1959/60. Taking into account his phobia regarding oil on canvas, did he encourage you to continue in that vein? Robert Barnes: Yeah, he was very encouraging... because Duchamp had caused this disaster in the art world. Even during his lifetime he was beginning to realize that this was really an uncomfortable and ugly situation, people who mistook novelty for invention. And I think he'd like someone who … well his whole bet was to follow what you are. I couldn't be like him, I couldn't even be like the surrealists. I certainly enjoyed their thinking, but I couldn't go that way. I just did what I did and I still am. It makes you unpopular, maybe for a lifetime, but I'd rather do that than be popular and doubt what I am.

Notes

4.

Long

after the interview, it came to my attention that Virginie Monnier

- in her "Catalog of Works" published in Jean Clair's (ed.)

Balthus exhibition catalogue for the late artist's major retrospective

at the Palazzo Grassi, Venice, 9 September 2001 – 6 January 2002 (Milan:

Bompiani, 2001) - had described Courbet's famous painting as incorrect.

Comparing it to an untitled pencil drawing by Balthus from 1963 (a

Courbet rasée, so to speak, though Balthus' adolescent model

might not have had any hair to speak of), which was obviously inspired

by Courbet, Monnier writes: "[I]ndeed it reproduces an anatomical

inaccuracy that in Courbet had caused outrage: the cleft of the vulva,

as thin as a line, goes all the way to the crease of the anus, ignoring

the anatomical particularities of the female body." (p. 388)

Figs.

4-6, 8, 9, 11, 14

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||