Recording of Marcel Duchamp’s Armory Show Lecture, 1963

[The following is the transcript of the talk Marcel Duchamp (Fig. 1A, 1B)gave on February 17th, 1963, on the occasion of the opening ceremonies of the 50th anniversary retrospective of the 1913 Armory Show (Munson-Williams-Procter Institute, Utica, NY, February 17th – March 31st; Armory of the 69th Regiment, NY, April 6th – 28th) Mr. Richard N. Miller was in attendance that day taping the Utica lecture. Its total length is 48:08. The following transcription by Taylor M. Stapleton of this previously unknown recording is published inTout-Fait for the first time.]

click to enlarge

- Figure 1A

Marcel

Duchamp in Utica at the opening of “The Armory Show-50th Anniversary

Exhibition, 2/17/1963″ - Figure 1B

Marcel

Duchamp at the entrance of the 50th anniversary exhibition

of the Armory Show, NY, April 1963, Photo: Michel Sanouillet

Announcer: I present to you Marcel Duchamp.

(Applause)

Marcel Duchamp: (aside) It’s OK now, is it? Is it done? Can you hear me? Can you hear me now? Yes, I think so. I’ll have to put my glasses on. As you all know (feedback noise). My God. (laughter.)As you all know, the Armory Show was opened on February 17th, 1913, fifty years ago, to the day (Fig. 2A, 2B). As a result of this event, it is rewarding to realize that, in these last fifty years, the United States has collected, in its private collections and its museums, probably the greatest examples of modern art in the world today. It would be interesting, like in all revivals, to compare the reactions of the two different audiences, fifty years apart. If only a happy few in this room actually saw the Armory Show of 1913, all of you have heard and read so much about it that we all are very familiar with the kind of reception the public of 1913 gave to it. It was a veritable bataille d’ [inaudible] with such weapons as derision, contempt, caricature, engaged in approval and defense of a new form of art expression, a battle which seems, today, hard to imagine.

click to enlarge

- Figure 2A

Interior space of the Armory Show, New

York (detail) 1913 - Figure 2B

Cover of the catalogue for “The Armory

Show-50th Anniversary Exhibition,” 1963

In Europe, this same period of 1910-1914 has been called the heroic epoch of modern art, and had its convulsions in the shows of the Independents and the Salon d’Automne of 1911 and 1912. But the reaction of the European public was only a mild cry of indignation in comparison to the negative explosion at the Armory Show. The public of 1963 will certainly not be shocked. All of the paintings and sculptures have been seen or reproduced so often during the last 50 years, and particularly after having been part of the controversy of 1913, most of them have established their worthiness. In other words (laughs), in other words, today, the public, in order to judge, will be on a more understanding and critical level, and fully aware of the concentration [inaudible] by the 50 years of survival. A feeling of reverence, with nostalgic overtones, will certainly prevail in the final verdict by our present aesthetic standards.

I hope, this afternoon, to add a little note to the Show itself, by showing you a number of works which were in the 1913 exhibition, but could not, for different reasons, be obtained for the present show. I will also show a few others, which, although in neither show, reflect the spirit of that period. The aim of the Munson-Williams-Procter Institute has been to show only the paintings and sculpture that actually were in the Armory Show. In fact, over 325 original items have been collected – a real tour de force. And now, we’ll start with the slides:

Ingres. Ingres. Dominique Ingres. Chronologically, the first artist on the list. Ingres was represented in 1913 by two drawings without any title in the catalogue. This one, a very beautiful study of a portrait he made of the Comtesse d’Haussonville (Fig. 3) was done around 1840, and may or may not have been actually in the 1913 Show. In any case, a drawing of such quality could compare favorably to any Ingres drawing, and we’ll accept it as though it had been, hmm? (laughter) It’s about the same.

Puvis de Chavannes next. Puvis de Chavannes. As a distant disciple of Ingres, Puvis de Chavannes applied a classical approach to the technique of mural painting during the middle and the end of the 19th century. In this Prodigal Son (Fig. 4), painted in 1879, Puvis de Chavannes seems to have completely ignored the realist storm of Courbet, followed by the Impressionists’ revolution, and all the isms that raged until he died in 1898. It shows courage—or stubbornness. (laughter)

Daumier. Honoré Daumier. Third-Class Carriage (Fig. 5) by Daumier. A very well-known masterpiece, which was included in the original show. Daumier made two other wash drawings of trains and their passengers, second and first class – when trains were quite a novelty, in the world of 1860. This oil painting now belongs to the Metropolitan Museum in New York.

click to enlarge

- Figure 3

Dominique

Ingres, The Comtesse d’Haussonville, 1845, The Frick Collection,

New York - Figure 4

Cover of the catalogue for “The Armory

Show-50th Anniversary Exhibition,” 1963 - Figure 5

Honoré Daumier, The

Third-Class Carriage, 1863-65, The Metropolitan Museum of Art,

New York

Manet. Manet. Édouard Manet, who died in 1883, painted some beautiful portraits in the last years of his life. This on, Mery Laurent (Fig. 6) —M-e-r-y, I don’t know why, hmm? Mery Laurent, the lady with the black cloak. Also called L’Automne, painted in 1882. It was included in the Armory Show, and is now in the Museum of Fine Arts in Nancy. Although Manet was on friendly terms with the Impressionists, he belongs to an earlier generation and never influenced or was influenced by any of their theories.

Degas. Edgar Degas painted this Carriage at the Races (Fig. 7), one of the many famous pictures Degas made of this scene. It was painted in 1873, when he returned from a trip to America, where he had visited his family in New Orleans, where his mother was a Creole. One still feels in this painting the mark of the Ingres and Manet influence, which disappeared in his later pastels of ballet dancers and washerwomen.

Redon. Odilon Redon. There are so many beautiful Redons …but this one is not perfect. This luminous pastel of 1910, called Roger and Angelica (Fig. 8), was among the fifty Redons shown at the original exhibition. Redon’s subjects were only simple incidents in the general arrangement of colors and forms. The figures and the faces in his pastels make no pretense at representing natural truth. They are more like the prolongation of dreams. And Redon’s pastels show the preoccupation of the non-figurative theories that we hear so much about today. (Today it’s abstraction.)

click to enlarge

- Figure 6

Edouard

Manet, Portrait de Méry Laurent, 1832-1883 - Figure 7

Edgar

Degas, A Carriage at the Races, 1872 © Burstein Collection/CORBIS - Figure 8

Odilon

Redon, Roger and Angelica, c. 1910, The Museum of Modern

Art, The Lillie P. Bliss Collection

####PAGES####

Now, we go back to the Impressionists.

Monet. Claude Monet was represented by five canvasses in the Armory Show. This first one,Boardwalk at Trouville, 1870, when Trouville was the Atlantic City of France, is an early attempt at Impressionism, since the name “Impressionism” was coined only four years later in 1874. And we have another Monet, entirely different. This one is a Water Lily Pool, on the contrary, dated 1904, much later, and is one of a series of water lily murals, which link Monet with the birth of abstraction. The two Monets that you saw were in the 1913 Show.

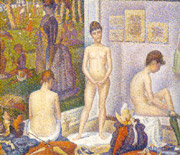

click to enlarge

Figure 9

Georges Seurat,

Les Poseuses (The Models),1888

Seurat. Georges Seurat, in his too-short life – he died at age 32 – achieved a very important revolution with Pointillism, which was his personal reaction to Impressionism. This beautiful version ofLes Poseuses (Fig. 9) of 1888, shows his very unique contribution to the technique of Neo-Impressionism. A large canvas of the same subject, Les Poseuses, is in the Barnes Foundation in Merion, Pennsylvania.

Cross. Henri-Edmond Cross was with Seurat and Paul Signac at the origins of Pointillism, the art movement that succeeded Impressionism around 1880. This painting, called Clearing(Fig. 10) of 1906-7, was in the Armory Show, and is a perfect illustration of the theories of Pointillism, based on the scientific studies of Chevreuil. Simultaneous contrast of colors which also influenced Delauney a few years later, around 1912.

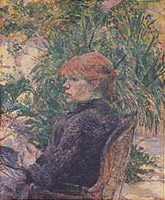

Toulouse-Lautrec. (I think we have it upstairs, I think) Toulouse-Lautrec is less known for his oil paintings than for his posters. Nevertheless, with paintings such as this one, calledRed-haired Woman Seated in Garden(Fig. 11) in 1889, he belonged to the Impressionist group. This painting was in the original show, and is also included in the anniversary show. (I saw it last night, hmm.)

Gauguin. Gauguin. Paul Gauguin brought back this oil from his first trip to Tahiti. It’s calledMata Mua (Fig. 12), which in Tahitian dialect means “in open times.” It was shown at the important Gauguin exhibition at the Durand-Ruel Gallery in Paris in 1893, when Gauguin was 45, already. As you know, he died in miserable conditions during his second stay in Tahiti in 1903.

click to enlarge

- Figure 10

Henri-Edmond

Cross. The Clearing, c. 1906/07 - Figure 11

Henri

de Toulouse-Lautrec, Red-Haired Woman Sitting in Conservatory,

1889, private collection - Figure 12

Paul

Gauguin, Mata Mua, 1892

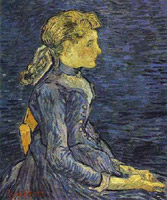

And van Gogh. Van Gogh. Of the 14 paintings that Van Gogh had in the 1913 show, five important ones are in the anniversary show, upstairs. This one, called Hills at Arles, from the Thannhauser Collection was painted in 1889 at Arles or at St. Remy, I can’t be sure. When van Gogh was very sick in the hospital at St. Remy. I show you now another landscape very much like this one. Olive Trees at St. Remy, painted in the same year, 1889. Very luminous expression and all – almost the same thing. In the following year, 1890, van Gogh went to live his last month in Auvers, a small town near Paris, where he painted several portraits of young girls like this one, Mademoiselle Ravoux (Fig. 13), June 1890, which is included in the anniversary show. Van Gogh died a month later. Incidentally, this last painting used to belong to Katherine Dreier, who lent it to the Armory Show, and it is now in the Cleveland Museum of Art.

And now we come to Cézanne. Paul Cézanne. Woman with a Rosary (Fig. 14). It was in the Show of 1913. Cézanne painted this important portrait at the end of his life in about 1903, probably in Aix [en-Provence]. In 1904-1905, the Salon d’Automne and the Independents gave him a very important one-man show. He died in 1906, before he had received a worldwide recognition.

Now we can do Ryder. Albert Ryder, a great, great painter, who came from an American Cape Cod family, and lived for many years in New York, on Washington Square and later, West 15th Street, in a most modest and bohemian way, completely absorbed in and dedicated to his inner vision. This Moonlight Marine (Fig. 15) was in the original and is also in the present show. It’s one of Ryder’s best-known themes, a typical expression of his position as a forerunner of abstract art, as we understand it today. Very abstract, isn’t it? You hardly see the boats. There are some boats.

click to enlarge

- Figure 13

Vincent

Van Gogh, Mademoiselle Ravoux, June 1890 - Figure 14

Paul Cézanne,

An Old Woman with a Rosary, 1900-04 - Figure 15

Albert Pinkham Ryder,

Moonlight Marine, c. 1908, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New

York

Figure 16

James McNeill Whistler, The

Little Rose of Lyme Regis, 1895. Oil

on canvas.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA, USA.

Figure 17

Mary Cassatt,

The Bath, 1910

Now, Whistler. James McNeill Whistler painted this portrait called Little Rose of Lyme Regis (Fig. 16), which is, I suppose, a small town in England. It was painted in 1895, and it is considered as one of his finest achievements in quality, as compared to most of his life-sized portraits. As we all know, Whistler lived a great part of his life abroad, and became quite a big international figure around the turn of the century.

Another American, Mary Cassatt is coming now. Mary Cassatt had two paintings in the 1913 show of her favorite subject, mother and child. She only painted that, all her life, very much like this one called The Bath(Fig. 17), 1910. That was not in the Show, I don’t think it was in the 1913 Show. In France, where she spent most of her life, she was very closely associated with the Impressionists—Degas, Pissarro, Berthe Morisot—and considered one of theirs. This painting is owned by the French government in the Petit Palais collection in Paris.

Now, we have the lights. Before we go on with the slides, I wanted to elaborate a bit on the art situation in America in the years before 1913. In New York, the private gallery of Alfred Stieglitz, Fifth Avenue, situated at 291 Fifth Avenue, although concerned with the establishment of photography as an art, was the scene of the introduction of Rodin, January 1908, and Matisse, April 1908, to America. I mean they didn’t come, only their things came, hmm (laughs). Stieglitz and Steichen, during the next years, followed up by showing Toulouse-Lautrec, Henri Rousseau, Cezanne, Picasso, and the American Max Weber. In 1910, the 291 Gallery gave a group show of American artists: Marsden Hartley, Dove, John Marin, Alfred Moore, Walkowitz, and others.

####PAGES####

Quite independently from 291, and more like a gesture of revolt against the Academy, a group of American artists held an exhibition in 1908 at the Macbeth Gallery in New York called The Eight Show. Robert Henri, John Sloan, George Luks, William Glackens, Ernest Lawson, Everett Shinn, Arthur B. Davies, and Maurice Prendergast. The show of The Eight at the Macbeth Gallery was a tremendous success, and was soon followed by the creation of a Henri School of Art, headquartered in the famous Lincoln Arcade Building, where lived myself later on, on 66th Street, where a large group of younger artists, like Bellows, Stuart Davis, Edward Hopper, Walter Pach, joined the ranks of the original Eight, under the guiding spirit of Robert Henri. The group was to be called, much later, the Ashcan School, which, to a certain extent, was a prophecy of what we know today as a proper art school, hmm?(laughter) In April 1910, a large independent show was organized by Sloan and Walt Kuhn. The great success of the show established firmly the faction of the young American artists in opposition to the Academy.

Such was the climate in which Arthur B. Davies, elected president of the newly-formed Association of American Painters and Sculptors in 1912, conceived with Walt Kuhn and Walter Pach, the project of an expanded version of the 1910 Independent with the participation of European artists. The project materialized in the Armory Show of 1913. Among the difficulties to organizing this large exhibition, the first important obstacle was the duty imposed on all import of all fine arts to America at that time. It was a remarkable decision of John Quinn, the famous New York lawyer and art patron, to go to Washington, and argue and convince the lawmakers to change the law. He succeeded, and obtained the admission duty-free of all fine original works of art to America less than a hundred years old, I believe. This action is still enforced today. Now, we will see more, more, more slides.

Yes. This is Henri. Robert Henri. Robert Henri was really a moving spirit of American modern art, in the period immediately preceding the Armory Show, though he was a finer teacher than a painter, in my opinion. This painting called Laughing Boy (Fig. 18) was not in the original show, but in the show of The Eight I spoke of, in 1908. It is a typical Henri portrait, but still too academic, I feel. The Ashcan is [inaudible]. (laughter)

Bellows. George Bellows, one of Henri’s pupils, belongs to the generation of the Ashcan School, and he is known for his pictures of boxing matches, executed in a dynamic narrative style. This view of Lower Manhattan called The Lone Tenement (Fig. 19) was painted in 1909, after Bellows had been accepted by the Academy in 1907, and before he began painting sports scenes of violent realism, which is more the Ashcan, like boxing.

Prendergast. A beutiful Prendergast. Maurice Prendergast spent his formative years in Europe. When he returned to America, he was invited to join the exhibition of the Eight in 1908 with Arthur B. Davies, Ernest Lawson, and the Henri group. He also showed at the Independents, 1910. Later on, Prendergast, Glackens, Bellows, and Charles Sheeler were among the founders of the second Society of Independent Artists – no jury – in 1917 in New York. This painting, called Ponte della Paglia (Fig. 20), was probably painted in Italy in 1899, I think. The flag is green. It’s an Italian flag in 1899. It shows, perhaps, an influence of Bonnard. It’s very true for the one in the anniversary show, upstairs, in the collection of this institute, Landscape with Figures. I remember, Prendergast was a very nice person. Very…very…almost timid.

click images to enlarge

- Figure 18

Robert Henri, Dutch

Joe (Jopie Van Slouten), 1910 - Figure 19

George

Bellows, Lone Tenement, 1909 - Figure 20

Maurice

Prendergast, Ponte della Paglia, 1898-99, The Phillips Collection,

Washington

Now, Walkowitz. Walkowitz is 82 now, today—82 years old today. He was born in Siberia, and came to the United States as a child. The title of these three drawings is Duncan Dancers(Fig. 21). Walkowitz made a great number of studies and drawings in the Isadora Duncan School of Dance. His sketches of Isadora and her pupils are a very vivid evocation of the great American dancer and teacher. At the time of the Armory Show, he was with the Stieglitz group.

Katherine Dreier. Katherine Dreier sent this oil, The Blue Bowl, and we never could find it. It is certainly not lost, but we couldn’t find it. At the Armory Show, she had spent several years in Europe, and brought back a small collection of European artists, among which is van Gogh’s Mademoiselle Ravoux, that you saw on the screen a moment ago. As a pioneer of abstract art, she established a few years later the Société Anonyme and The Museum of Modern Art of 1920, long before the other Museum of Modern Art. A collection of international artworks, which is now at Yale University.

Kroll. Leon Kroll. You can hardly see it, it’s from a newspaper, but anyway. He painted this painting called Terminal Yards (Fig. 22) around 1911, and it was in the 1913 Show. Unfortunately, I have been unable to find a better slide. This one is taken from a newspaper reproduction. The painting was bought at the Armory Show by Arthur Jerome Eddy, a Chicago lawyer and art collector, a rather eccentric character – he bought two of my own paintings, (laughter) and was the first man in Chicago to have his portrait painted by Whistler and to ride a bicycle (laughter). You know, I knew him and he was very nice man.

Rousseau. Rousseau, Rousseau, Rousseau. Le Douanier has three landscapes in the present show, very much in the spirit of this one, which is called View at Malakoff (Fig. 23).Malakoff is a small town on the outskirts of Paris, dated 1898. I think it was also in the original Show, and I want to show you a bigger one, which was not in the Show. And now, in another vein, which accounts for his fully-deserved recognition, Rousseau becomes the dreamer, the poet in these large paintings like this one, called The Dream, painted in 1901.

click images to enlarge

- Figure 21

Abraham

Walkowitz, Isadora Duncan, date unknown - Figure 22

Leon Kroll, Terminal Yards, ca. 1911 - Figure 23

Henri

Julian Rousseau, Study for View at Malakoff (Vue

de Malakoff), 1908

click to enlarge

Figure 24

Wilhelm Lehmbruck, Kneeling Woman

(Femme á genoux), 1911

click to enlarge

Figure 25

André Derain, Window on the Park

(La Fênetre sur le parc), 1912

Lehmbruck. Wilhelm Lehmbruck has been called the leading Expressionist sculptor. In this Kneeling Woman (Fig. 24) of 1910, he is simply turning away, turning his back on the pure forms of Maillol, whose influence had marked his earlier years. The plaster cast of this sculpture was in the original show in 1913 and belongs now to the Albright Gallery in Buffalo. But it is too fragile, really, to travel. You can only see it this way.

Derain. One of the original “wild beasts,” the Fauves, with Matisse and Braque. Derain turned, after 1907, to a more constructive technique. Almost a Cubist, without accepting to be a Cubist. He was very stubborn, too. And his still life, Window on the Park (Fig. 25), 1912 belongs to the Museum of Modern Art in New York, was in the original Show, and is also in the present show.

Pablo Picasso. This portrait of Madame Soler is a very early Picasso, dated 1903. It belongs to the blue period, probably painted in Barcelona, where he had returned after his first stay in Paris, 1901-1902. One of the very first Cubist sculptures by Picasso, this Head of Fernande Olivier, 1909, is treated with the same facet-like technique as were the Cubist paintings of the same year. Yes, it’s in the present show. It’s upstairs. Beautiful sculpture. Now, we have another one, which is called Woman with a Mustard Pot(Fig. 26), you see the mustard pot on the left, and was painted in 1910, at the very beginning of Cubism, and bears a certain resemblance to the sculpture you just saw on the screen. The museum of The Hague, Holland, agreed to lend this important painting to the show in New York in April. They wouldn’t let it go for more than three weeks, I don’t know why. The three Picassos you just saw were all in the original Show.

####PAGES####

Now, this is Brancusi. Constantin Brancusi. I cannot understand why this beautiful Muse(Fig. 27) and four other sculptures of Brancusi’s, created such a violent reaction in the Chicago show of 1913. As a result, Brancusi was burned in effigy, along with Matisse and Walter Pach, in Chicago (laughter). It’s true. These are the mysteries of modern art.

Braque. Georges Braque, in 1908, Georges Braque abandoned his Fauvist palette and attacked a completely different problem, which was to become Cubism. This still life, Pitcher and Violins (Fig. 28), 1910, is typical of the first years of the Cubist discipline as it was practiced by Picasso and Braque at that time. In fact, their technique was so closely similar that it was very difficult at times to distinguish the Cubist Braque from the Cubist Picasso. That I know, that was very difficult.

Léger. Fernand Léger. I remember seeing this composition by Léger in the Cubist room of the Salon d’Automne in 1911. Léger’s contribution to Cubism in 1910 and 1911 was this tubular style. Instead of using cubes, he used tubes. The art critics of the time called him a Tubist instead of a Cubist (laughter). It’s true, it was in all the papers. He was soon to develop a more colorful style.

La Fresnaye. La Fresnaye. Roger de la Fresnaye was wrongly called a Cubist. In this Village of Meulon of 1912, he simply applies a geometric technique, a formal transcription of a very effective landscape. This painting is now in the Philadelphia Museum of Art in the Arensburg collection, and probably was in the 1913 Show. Probably. When I first came to New York in 1915, it was hanging in the Arensburgs’ dining room. They probably bought it at the Show, that’s why.

click images to enlarge

- Figure 26

Pablo Picasso, Woman with

Mustard Pot (La Femme au pot de moutarde),1910 - Figure 27

Constantin Brancusi, The Muse (La Muse),

1912, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York - Figure 28

Georges Braque, Violin and Pitcher, 1910

click to enlarge

Figure 29

Francis Picabia, Procession in Seville, 1912

Voila. It is Picabia. I also remember being in the studio with Picabia in Paris when he was making this Cubist picture,Procession in Seville (Fig. 29) in 1912. His main preoccupation at that time was to advocate abstraction, and he must be counted with Kandinsky, Kupka, and Mondrian as one of the pioneers of non-figurative art. This painting was in the Armory Show and is also included in the anniversary show.

That’s my brother. Duchamp-Villon. Not himself, no (laughter). Duchamp-Villon, my brother, has three pieces in the present show. This one, his fourth piece, called Girl of the Woods, was made in 1910, I believe, a year before his head of Baudelaire and two years before his Cubist horse. It is a terracotta cast of the original plaster which was in the 1913 show. He died in November of 1918, from the long illness he had contracted at the front in the First World War.

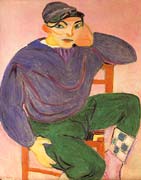

click to enlarge

Figure 30

Henri Matisse, The Young Sailor, II (Jeune Marin), 1906

Now we come to Matisse, who I have been keeping for the last because I want to show you five important ones, although we haven’t got many upstairs. Matisse was represented in the Armory Show by thirteen paintings, three drawings, and a large sculpture. While Augustus John had thirty-eight, and Odilon Redon forty. But Matisse had a big share of angry hostility on the part of the public and the art critics. Even though we’re now completely familiar with the five Matisses I’ll show you, we can imagine the shock they produced in 1913 on a public totally unaware of the “Wild Beast School,” the Fauves. This painting, The Young Sailor(Fig. 30) was done in 1906, in Collioure. It is the second of two versions, this more graceful and assertive than the first one. Now, the Blue Nude of 1907 painted also in Collioure, heavily accented in the Fauve style. It is now in the Baltimore Museum. This is Luxe, the second version of 1908. It has only the word “luxe” in common with an earlier painting of 1904-5 called Luxe, Calme, et Volupté, a title taken from the famous poem of Baudelaire,L’Invitation au Voyage. It is completely painted in Pointillist technique—the other one, not this one. Girl with a Black Cat. This is one of the numerous portraits Matisse made of his daughter Marguerite. It is dated 1910, a year of many Matisse portraits. And now, the last slide, The Red Studio, one of the four large interiors painted by Matisse in 1911. Against a monochrome red, Matisse has scattered the colored miniature images of his own paintings and sculptures. This last painting belongs to the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

And now, before we part, I would like to salute a few artists, veterans of the Armory Show. Archipenko, Georges Braque, Paul Burlin, Stuart Davis, Edward Hopper, Leon Kroll, Picasso, Monsieur [inaudible], Charles Sheeler, Jacques Villon, Walkowitz, Margaret and William Zorach, and myself.

(Applause)

Announcer: Lights!

(Applause)

[inaudible]

[cut]

Voice: Questions and answers – we’re never gonna get those.

[inaudible]

Marcel Duchamp: Yes. I don’t know because what you do in 1913 you don’t do in 1963, even anybody. It is very difficult to say. I might and might not. I don’t know, I couldn’t tell. And you don’t know either. I have a cigar now (laughter and applause). Thank you.

[end of recording]