“Macaroni repaired is ready for Thursday….” Marcel Duchamp as Conservator

“…while not as world-shaking as war, [Duchamp’s art] certainly has outlived

the latter. The survival of inanimate objects, of works of art through great

upheavals, is one of my consolations. My justification, if need be.”

(Man Ray, Self-Portrait,1963)

Marcel Duchamp’s reputation involves a profound insouciance, and an apparent disregard for his own artworks. One of modernism’s most enduring myths is that, once an artist creates a work, it is launched into the world and endures on its own. James Joyce articulated this ideal in Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916): “The artist, like the God of the creation, remains within or behind or beyond or above his handiwork, invisible, refined out of existence, indifferent paring his fingernails.” Joyce’s meaning is more deeply imbedded in notions of reception and the autonomy of the text, to be sure, but it can also be extended to describe an artist’s post-creative strategies. Indeed, Joyce was notorious for his endless revisions and for the extensive post-publication relationship he maintained with his works. Similarly, throughout his life, Duchamp maintained an intimate relationship with them, personally conserving, repairing, cleaning and preserving them. Indeed, such behaviors accounted for much of his private activity in the second half of his career.

click to enlarge

Illustration 1

Photograph taken in Katherine

Dreier’s West Redding,

Connecticut, home; summer 1936.

A photograph from 1936, taken in Katherine Dreier’s Connecticut home, suggests this more prosaic side (SeeIllustration 1). Wearing a pullover rather than his usually natty clothes, a five-o’clock-shadowed Duchamp stands wearily next to the Large Glass (1915-23) which he had just spent weeks reconstructing. This image, as well as Man Ray’s quote above, begs an interesting question. How is it that the unconventional and often fragile works of an artist who publicly eschewed those art world institutions that would normally be trusted to conserve them-dealers, galleries, museums-have come down to us in relatively fine condition, or indeed, at all? (1)

Duchamp’s acquaintances knew him to be inordinately concerned with issues of conservation, no matter whose works were involved. Georgia O’Keeffe’s first meeting with Duchamp was memorable for her not because of his outrageous behavior but because of his sober concern for artworks.

He was consulted in all matters pertaining to conservation. He arranged for the restoration of twenty-one damaged pictures by his brother-in-law Jean Crotti, and was then asked to have their Renoir paintings restored towards a new valuation of them. (3) Duchamp demonstrated particularly selfless devotion to the artworks of his friend and patron, Katherine Dreier. In 1951, at her request, Duchamp visited a church in Garden City, New York, to examine her 1905 mural The Good Shepherd. (4) Duchamp wished to supervise the restoration himself and, after inspecting it on a ladder with a “search light”–Duchamp was sixty-four-years-old at the time–he suggested no extensive restoration except the removal of the varnish and its subsequent waxing. ‘Waxing is much better than varnishing,’ he opined.(5) Duchamp’s judgment, it turns out, was technically sound. He eventually employed the services of the painter Fritz Glarner (1899-1972) who, he believed, was “an expert at cleaning paintings.” (6) After viewing the mural together, Glarner’s restoration took seven days, two hundred dollars, and Duchamp’s arrangements to draw money from a foundation set up for this very purpose. (7) Duchamp’s thoroughness in conserving his friend’s artwork–a piece that he must have known had little historical significance–is extraordinary. Moreover, he promised Dreier that, after this project was over, he would take her portrait of her father to New York for repair. (8) In startling contrast to his usual heightened concern for artworks, when Jackson Pollock’s Mural (1943, University of Iowa Museum of Art, Iowa City) would not fit the space for which it was painted–in Peggy Guggenheim’s apartment–Duchamp and David Hare cut off eight inches to make it fit. (9) This might be explained by his chill disinterest in abstraction, and by his pragmatism in solving problems. But it had been Duchamp who convinced Guggenheim to give Pollock his first one-man show, and it was he who suggested that Pollock paint the mural on canvas rather than directly on the wall so that it could be exhibited publicly.

As one might expect, whenever Duchamp was engaged in buying and selling artworks he was especially attentive to their condition. For instance, he sprang into action when the collector Jacques Doucet expressed interest in a slightly damaged Picabia collage, Plumes(ca. 1923-27), made of feathers, macaroni, cane and corn plasters; it was one of the works from the ’80 Picabias’ exhibition at the Hôtel Istria (Paris) which Duchamp had organized. After personally repairing it, he wired Doucet: “Macaroni repaired is ready for Thursday….”(10) And about the Picabia works he himself owned, also made of unconventional materials, Duchamp told Doucet that he would not consider selling them “except in conditions guaranteeing the precious side of these things.” (11)

In his capacity as dealer for Brancusi’s sculptures, Duchamp was often faced with delicate situations involving condition. Once, a small crack had been discovered in the white marbleBird in Space which was in transit to the 1933 Brummer Gallery exhibition. Characteristically resourceful, Duchamp found a way to exhibit it so that the crack was not noticeable. (12) And he was particularly watchful of the Brancusis in Dreier’s collection. He reminded her to move “the marble bird and the soft stone piece [the base]” of the BrancusiMaïastra out of her West Redding, Connecticut, garden for the winter. It had been Duchamp himself who had sold it to her. (13) Still, he realized that conservation was not its own end; it was a function of proffering sales, too. Years later, Duchamp advised Roché to accept an offer for Brancusi’s La Colonne sans fin which had stood for a long period outside Dreier’s home. After it had split in the back, “restorers” had painted it black. (14)

Duchamp’s concern for his own pieces is first of all apparent in his careful selection of materials. Although he used an enormously expanded range of media, he did so with an abiding concern for their durability and for protecting them. Early in his career Duchamp fantasized about the use of such unconventional materials as toothpaste, brilliantine, cold cream, shoe polish, and chocolate on glass. But he would only do so, according to his notes, if the works made from them could be cleaned. (15) His attitude had not changed when, four decades later, he used talcum powder and chocolate for a delicate landscape, Moonlight on the Bay at Basswood [Minnesota] (1953). He may have turned to these materials in the first place since he had no traditional artist’s materials on hand, and perhaps to compensate for the conventional nature of the work (a fairly straightforward landscape). In any case, his concern with the work’s well-being manifest itself when, within an hour of offering the recently made landscape to his patron, Duchamp “hastily” made a frame for the image “to protect the fragile surface from brushing against something and being marred.” (16) He later expressed his worries about the piece saying that he “hoped it will last and the poor chocolate, I’m afraid, will disappear or get white.” (17)

Modernists using non-traditional materials have often demonstrated obsessive concern about the condition of their pieces. Arthur Dove (1880-1946), for instance, whose dazzlingly advanced collages employ a broad range of unconventional materials, worried about the longevity of his works. Towards this end he read extensively on the subject of permanency, grinding his own colors, priming and stretching his own canvases, and even making his own pastels. (18)

As a painter, Duchamp had showed a decided preference for high-quality products. Robert Lebel observed that the artist’s “scrupulous study of paints and their properties led him to select the German Behrendt brand which he used exclusively.” (19) Duchamp established this preference–because of its reputation for permanence–during his brief Munich sojourn (1911-12) on the advice of his German friend, Max Bergmann. The Bride (1912) is painted with these pigments, which were, as Calvin Tomkins corroborates, “the best brand available.” (20)

Indeed, Duchamp lived long enough to test their quality. When his forty-year-old Portrait of Dr. Dumouchel (1910) arrived at the Arensberg’s very dirty, the artist assured them that they “will have no difficulty” cleaning it. He was confident that the restorer would recognize that it was made with Behrendt paints. Afterwards, Duchamp smugly confirmed he “was sure that Dumouchel [would] be surprisingly fresh after Miss Adler’s shower,” (21) “shower,” of course, being Duchamp’s anthropomorphizing euphemism for a cleaning. Looking back at paintings made decades earlier, he was generally pleased that many of them had remained stable and fresh looking. Referring to the pigments in his Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (1912), for instance, Duchamp observed (1966) that “they’ve behaved very well, and that’s very important.” (22) Similarly, he had once boasted to Jasper Johns (1960) that the lacquered dust in the Large Glass was “just as good today as it was thirty years ago.” (23)Duchamp had beamed about the physical condition of that work to another interviewer a few years earlier. “Thank God, the color still looks fresh. It’s not a faded flower, not like an old master in a museum….” (24)

Such was his sensitivity to materials that when he was asked his opinion about the future of painting, he often took it to mean the medium rather than the genre. “One can forget oil painting,” Duchamp said in a late interview. “It discolours. It needs repairing all the time. Yes, one can find something else.” (25) Though his response may have been a defensive strategy with which to sidestep empty speculation about then-current art trends, it is nonetheless interesting that it took this form. When Duchamp critiqued the commercial end of art, it was often by addressing the vulnerability of art objects:

His resentment at easy sales is here expressed as a remonstrance about bad workmanship. At this particular moment his anxiety about the longevity of art may have been particularly acute. His public career had by this time greatly diminished and, more troubling still, Duchamp had just seen the destruction wrought upon his Large Glass first-hand.

Duchamp first considered using glass as a support in his artworks in part because it promised longer preservation for the pigments. (27)

Duchamp’s glass works required careful, sustained maintenance because of its fragility and since glass naturally reveals its dirt more conspicuously. (29) Duchamp’s friend H.-P. Roché remembered that the Large Glass was “washable on both sides under the shower,” and, as opposed to canvas, acquires “no dust on its backside.” (30) Still, such cleanings must have been complicated affairs. Duchamp once wrote Jacques Doucet to say that cleaning Glider Containing a Water Mill in Neighbouring Metals (1913-15), which Doucet had recently purchased, “will take me 2 or 3 afternoons.” (31)

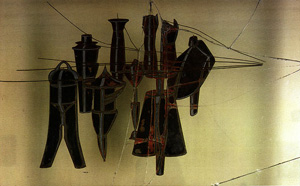

click to enlarge

Illustration 2

9 Malic Molds,1914-15,

painted glass, wire and sheet lead.

Teeny Duchamp Collection,France.

Though they may have preserved the materials applied to them, and though they may have been cleanable, Duchamp’s glass works were predictably vulnerable and underwent a dizzying history of damage and repair. For instance, the Nine Malic Moulds (1914-15) was first broken when it was placed against an armchair on castors which rolled away (SeeIllustration 2). Left temporarily at the apartment of a friend, Roché noticed later the same year that the work had scratched the piano. After it cracked once more, this time in the possession of another friend who placed it too close to the fireplace, Duchamp and Roché took it to the well-known framer Pierre Legrain. (32) It seems its greatest danger came from the casual treatment of the people who putatively cared for it. This must have been a sobering lesson for Duchamp who became even more attentive to his works’ conditions in the years that followed.

Decades later, he again turned his attention to the long-term safety of Nine Malic Moulds. “I was wondering if you could have your glass reframed in a manner more solid and definitive,” he wrote to Roché in Paris who now owned the piece. He outlined a complex process whereby its custom-made frame could be removed, the glass cleaned, and a new frame put around it. “Leave the mastic to dry several months without moving the glass,” Duchamp insisted. About a month later, he wrote again, repeating his instructions for strengthening the piece and conveying his concerns for its future: “If the glass must travel, it is essential that it arrives in perfect shape ‘for centuries to come.'” (33)

Given Duchamp’s concern for his artworks, one wonders if he would have made any of glass had he known their fate. Charles Demuth thought it so obviously unwise that he once lamented, “Dear Marcel, having used glass so often seems to have added difficulties for the Future–he would, of course.” (34) After the debacle of destruction and repair engendered by the Large Glass, he never made another work in that medium.

The major work of Duchamp’s early career, the Large Glass (1915-23), had only been exhibited once (Société Anonyme Exhibition, 1927) before it was broken en route from the Brooklyn Museum to Katherine Dreier’s home in West Redding, Connecticut. (35) Dreier conveyed the terrible news in Lille in 1933, where, over lunch, he could be expected to take the news with some restraint. Years later Duchamp recalled that, in order to spare Dreier’s feelings, he had gallantly expressed “a reaction of charity instead of despair.” (36) She may have been especially contrite since another of Duchamp’s glass works, To Be Looked at, (from the Other Side of the Glass) with One Eye, Close To, For Almost an Hour (1918), had earlier been broken while it was in her possession. Years after her death, Duchamp candidly described the broken Large Glass in painfully descriptive terms as “marmalade.” (37)

One wonders why Duchamp did not simply abandon the wrecked Large Glass at this point considering the extent of the damage and since his work on it had all along been fitful and inconclusive. And if the transparency of the glass were vital to the work, the cracks would severely compromise that. Why then, did Duchamp, notorious for his bored disengagement with art, go to such great lengths to restore it?

Having seen the devastated Large Glass in the autumn of 1933, he had some idea of the immense effort required for its repair. He informed Dreier of his plans: he had arranged to be in America for nearly three months, had studied an “invisible glue” with which to repair the work, and had conceived a plan to mount the reconstructed work between two heavy plates of glass. “Although very heavy,” Duchamp speculated, “it would make a solid[emphasis his; a gentle barb to Dreier?] piece of furniture when in place.” (38) Bearing a certain amount of responsibility for the damaged to the Large Glass, Dreier paid for everything connected to its repair, including materials and contracted labor. (39) She assured Duchamp of a room in her house, offered him thermoses of coffee, breakfasts on a tray in the mornings, and a carpenter on hand to assist in the reconstruction. (40) She even covered his passage to America.

It is a misconception that the Large Glass had merely cracked in the patterns one sees today, remaining more or less intact. In reality, except where some of the wire designs were holding some shards together, the work was reduced to an enormous pile of unattached fragments. Testimony is provided by an account in a local newspaper which described the carnage as “a 4 by 5-foot three hundred pound conglomeration of bits of colored glass.” (41)The title of another article, “Restoring 1,000 Glass Bits in Panels; Marcel Duchamp, Altho an Iconoclast, Recreates Work,” (42) called attention to the uncharacteristic manual labor now demanded of the notorious anti-artist involving gloves, glue pot and a pile of splintered glass. “It’s a job, I can tell you, ” Duchamp confessed to his interviewer, “like doing a jigsaw puzzle, only worse.” (43) Privately, he described his absorption in this gargantuan project:

And to Brancusi, he described this period as something of a nightmare, “I’m waking up…. For 2 months I have been repairing broken glass and I am very far from my Parisian ways.”(45) Dreier, in turn, complained to one of her friends about the artist’s monomania at this time: “Duchamp is a dear, but his concentration on just one subject wears me out, leaves me limp.” (46) Intimations that the artist was tiresome in conversation are exceedingly rare in the historical record.

The Large Glass became a different work in the course of restoration, a portion of its original, intricate iconography having been lost altogether. The upper right hand side of the work, including the “inscription du haut” (“top inscription”) and the “9 tires” (“9 shots”) figure, was so fragmented that Duchamp was forced to insert three new pieces of glass. He had the holes for ‘9 tires’ redrilled and the missing part of the ‘inscription du haut’ completely restored. (47) The area of the Bride’s “clothes” were also remade in three narrow strips of glass inserted horizontally between the upper and lower panels. The only section free of cracks is the one including part of the “Milky Way.” Ultimately, the work became a mixture of old and new, Duchamp’s restoration “completing” the unfinished work, as it were.

The present format of the Large Glass–the original glass sandwiched between two thicker planes all held together by a metal frame–was a contingency of the restoration. Duchamp had previously repaired the broken To Be Looked at (from the Other Side of the Glass) with One Eye, Close to, for Almost an Hour (1918) in this fashion and, satisfied with the result, performed a similar operation on Nine Malic Moulds (1914-15) a couple months later. (48)By the time he addressed the restoration of the Large Glass, the repair strategy was a familiar one. After completing the restoration of the Large Glass, Duchamp regarded it as a different work than the one he had begun more than two decades before. Along with the title, he now inscribed the words “-cassé 1931/ -réparé 1936.” He apparently felt that the history of the piece, including its restoration, was important for viewers to know.

click to enlarge

Illustration 3

3 Stoppages Étalon(Standard Stoppages), 1913-14, wood, glass, threads, varnish and glass. Katherine S. Dreier Bequest, The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Duchamp used his restoration junket to Connecticut to conserve other of his works in Dreier’s collection. He had theRotary Glass Plates (Precision Optics)(1920)–which Dreier had been unable to locate–and the 3 Standard Stoppages(1913-14) (See Illustration 3) taken out of storage. He cleaned, reassembled and replaced the motor on the former. And it was only at this time that 3 Standard Stoppages assumed its final shape. He mounted the three narrow canvas shapes on glass and photographed them against the clapboarding of Dreier’s house. This provided something of a grid background for the photograph of the piece that would be included in the Boîte en valise. (49)Duchamp altered a long, wooden croquet-mallet box to hold both the glass plates and the original wooden “yardsticks.” Indeed, much of the format of the piece, as we shall see, is a function of his concerns for its preservation.

Not just an engineering problem to be solved, the damage to the Large Glass jolted Duchamp’s sense of his career. It occurred when his production of artworks had virtually stalled, perhaps just when his sense of himself as an artist was particularly vulnerable. Calvin Tomkins has observed that “the shattering of Duchamp’s most important work seemed like one more confirmation of his decision to give up being an artist.” (50) Surveying the damage and undertaking its repair galvanized his resolve to enter that phase of his career which involved the large-scale reiteration and reproduction of his works in multiples. Jean Suquet has observed that even before Duchamp began repairing the broken Large Glass, he first published the Green Box (Paris, 1934). “Only then,” Suquet says, “did he restore the image between two new plates of glass, now to be read through the foundational grid of his writings.” (51) The artist himself admitted that “the notes [in the Green Box] help to understand what it [the Large Glass] could have been.” (52) The following year, perhaps still reeling from the destruction of his major work, Duchamp began thinking of making an “album” of all that he had made until then. This would later be realized in hundreds of copies as the Boîte en valise–for all intents and purposes a portable museum of his most important artworks.

Indeed, the damage wrought upon the Large Glass had provided dark inspiration for theGreen Box. The scraps of paper in the Green Box reminded a startled Katherine Dreier of the broken shards of the Large Glass. (53) Duchamp himself mused about the appropriateness of splinters and shards for their historical moment. He told his author friend Anaïs Nin that the form of the Green Box–which, as a box of scraps resembled the crate full of shards that was now the damaged Large Glass–should replace the conventional codex, adding, “It is not the time to finish anything. It’s the time of fragments.” (54)

It is part of the Duchamp legend that the artist viewed the destruction of the Large Glasswith dispassionate resignation. The artist himself helped give this perception currency. The filmed interview, “A Conversation with Marcel Duchamp,” with James Johnson Sweeney at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (1956), opens with Duchamp looking at the Large Glass. He first recounts the story of the damage to the work then adds, “The more I look at it, the more I like the cracks.” (55) This appears to be the first intimation that the breakage was part of an “incorporation of chance” in the work. The legend of Duchamp’s appropriation of accident into the work’s aesthetic later gained momentum through John Cage’s advocacy of aleatory effects. Some observers, however, found nothing enchanting nor conceptual about the damage. “Anyone can get their painting wrecked,” quipped one critic. (56)

Duchamp, too, seemed to realize that the restoration could not make the work pristine again, nor would the cracks make it a more interesting work. Worried how a museum might regard the repaired Large Glass-before it had found a permanent home-he sullenly speculated, “I have a hunch that broken glass is hard to swallow for a ‘museum.'” (57) In the end, Duchamp regarded the piece as a broken and repaired work of art. Asked in another filmed interview a decade later whether the cracks in the glass are fundamental to the work, he responded simply and definitively, “No, no.” (58) Poignantly, he once downplayed its damage describing it not as a “ruin,” but merely “wrinkled.” (59) Likewise, Duchamp would have been saddened-not delighted as is often claimed–to learn that the replica of “In Advance of the Broken Arm” (1915), the show shovel readymade, was used by an unwitting janitor to clear the sidewalks outside an exhibition of his works. (60) By now it is clear that he could not have looked smilingly on such lapses in conservation. Such legends gain plausibility by confusing the nonchalant provocation of his art with his professional aspirations. Duchamp’s reconstruction of the Large Glass is seldom recounted in the literature, for much the same reason. But it demonstrates his profound concern for his works and his willingness to endure much hardship and tedium to restore them. Certainly, there exists no other modern artwork of the same calibre as the Large Glass on which its author labored so intensively to restore it.

Since Duchamp had never surrendered his works to a dealer, at least until the last few years of his life, his pieces were not scattered widely across private collections. And because he was obsessive about keeping his relatively small oeuvre together, he had unique access to his works. Thus, he could more easily track their whereabouts and monitor their conditions. Although Duchamp’s concern for his works’ preservation was an ongoing one, his efforts along these lines accelerated in the late 40s and early 50s. This was the period when his historical reputation was being consolidated through increasing exhibitions and a burgeoning literature devoted to him. This was also the period when the Arensbergs were looking for a museum to which they would bequeath their collection. Reassured that they already owned most of his artworks, Duchamp nevertheless felt personally responsible for maintaining them.

click to enlarge

Illustration 4

King and Queen Surrounded by

Swift Nudes, 1912, oil on canvas.

Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection,

Philadelphia Museum of Art.

When he visited them in April, 1949, for example, he discovered that Paris Air (1919), a sealed glass ampule, had broken. He had already mended it once before, but now the damage seriously compromised the integrity of the piece. Duchamp wrote a letter to Roché in Paris requesting that he procure a similar ampule from the same pharmacy from which he had bought the original. (61) In the same spirit of conscientiousness, in 1952, as the Arensberg Collection was destined for permanent display at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, he retouched his painting Paradise (1910). (62) He had hoped to rectify a considerable craquelure that can still be seen in the painting on the back, The King and Queen Surrounded by Swift Nudes (1912) and lamented “Unfortunately this picture has not stood time as well as my other paintings….” (See Illustration 4) (63)

In general, Duchamp’s patrons shared his conservation concerns especially since some of his works required specific and unusual maintenance. For instance, the repaired Large Glass, now standing in Katherine Dreier’s home, had become a fragile, glass monolith. Because Dreier dared not move the piece, she considered converting her home into a “Museum in the Country.” (64) Still troubled by the matter at the end of her life, she confessed to Duchamp that she might not leave enough money to guarantee its upkeep and safety. (65) The issue was resolved only after her death when Duchamp–acting as her executor–decided that it should enter the Arensberg Collection in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, which already contained the preponderance of his works. That way, Duchamp knew, its maintenance would be assured–and the major work of his early career could stand beside his others.

It had been considerations of conservation that were critical to the choice of Philadelphia as the permanent home of the Arensberg Collection in the first place. The Arensbergs had been considering the Art Institute of Chicago until, during the period of loan for the exhibition “20th-Century Art from the Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection,” (20 October-18 December, 1949), an Alexander Calder sculpture of theirs had been broken (Mobile, 1934), and the frame of a Fernand Léger painting (The City, 1919) had been repainted without their permission. Moreover, the Arensbergs found some of the display construction shoddy and the overall presentation rough and unprofessional. (66)

Duchamp regarded the exhibition of his works as an opportunity to inspect them and, if necessary, to conduct repairs and conservatorial measures. On one occasion, he asked Michel Sanouillet to bring “two bottles of crystal mastic varnish” from Paris to the opening of the 1951 Sidney Janis Gallery (New York) exhibition, “Brancusi to Duchamp,” so he could treat his two paintings on display there. (67) Duchamp would apparently not settle for any varnishes he could have bought locally. After seeing his Genre Allegory (George Washington) (1943) at a MoMA exhibit (1948), Duchamp was troubled that the original deep-blue background had faded. He asked André Breton, its owner, if he could repaint the blue before the work returned to Paris. (68) It is not known whether he ever performed the retouching, but it is noteworthy that the work was only five years old at the time. Remarkably, Duchamp did not always require a first-hand look at his works to proceed with conservation. After seeing a photograph of Coffee Mill (1911), which was to be used as a reproduction in Lebel’s monograph on the artist, he recommended the painting receive “a very thin coat of transparent varnish.” (69)

As we saw in the repair of the Large Glass and in the conservation of Dreier’s mural, Duchamp generally heeded the judgment of professionals. For example, in response to an Art Institute of Chicago conservation report for one of his earliest paintings, Garden and Chapel at Blainville (1902), he agreed to have a new stretcher and liner made for it. (70)More often than not, however, the conservation of works already in museum collections involved cajoling institutions, the search for funds, contacting restorers and the like, all of which Duchamp himself was willing to undertake. He once expressed his anxieties about the rapid deterioration of works in the collection of the Société Anonyme to its director, George Heard Hamilton. Informed there was no money for conservation, Duchamp volunteered to approach Mary Dreier, sister of his deceased friend Katherine Dreier. After their meeting, he wrote Hamilton again, this time asking for a more detailed account of the conservation costs including–and this was his own plan–a capital sum for an endowment specifically devoted to that purpose. In the end, Mary Dreier was unable to fund an endowment but contributed $1,500 per year for conservation during her lifetime. (71) Not only had Duchamp originally helped amass the collection of the Société Anonyme, he had now provided for its long-term conservation.

Over the course of his career, Duchamp came to understand what every art mover, preparator, and curator knows: that artworks are most vulnerable while being moved. His own glass pieces had undergone a gauntlet of destruction brought largely about by their transport. These moves were a continual source of anxiety for both the artist and for his patrons as well. After patiently waiting years for Duchamp to finish the Large Glass, the Arensbergs sold it to Dreier when they moved to California in 1923. Presciently, and ironically, they feared it might be damaged in the move. (72) Not just those of his glass works, his paintings also sustained damage while in transit. The renowned Nude Descending a Staircase, #2 (1912) was torn slightly during its loan to the “Three Brothers” exhibit at the Guggenheim Museum (1957). Duchamp, along with a professional restorer, determined that the one-inch-long tear in one of the darker areas of the picture and some missing paint was not terribly serious. The artist suggested a temporary repair so that it could travel to its next venue. (73) Aware of the high degree of risk in moving artworks, Duchamp sometimes insisted on specific travelling guidelines for his pieces. Roché, who owned the repaired Nine Malic Moulds (See Illustration 2), received lots of advice along these lines, especially when it was to be exhibited. “For your glass, have it carried by someone, upright,” Duchamp suggested, “as we did for the Surrealist exhibition at Wildenstein’s [Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme,” Paris]. A year later, he thanked him for personally walking it to the Musée National d’Art Moderne show, “Le Cubisme 1907-1914.” Concerned about the piece travelling twice across the Atlantic–so it could be exhibited in the “Three Brothers” exhibition–Duchamp asked Roché if he would consider selling it while it was in America.(74) In making this request he was shrewdly killing two birds with one stone: it would lessen the risk to a glass work in transit, and also move the piece closer to the preponderance of his oeuvre. It appears that Duchamp implicitly charged his patrons with a certain level of safeguarding for his artworks. When the Arensbergs were to send him Paradise/The King and Queen Surrounded by Swift Nudes/Paradise (1910/1912), he told them that special insurance would be required since his New York studio was not fireproof. (75) A justifiable respect for fire was reflected in his assent that, if the Art Institute of Chicago wished to borrow his avant-garde film Anémic Cinéma (1925-26), they should first have a non-flammable copy made. (76) Such premeditated concerns work against Duchamp’s reputation for heedlessly courting the vicissitudes of fate.

Packing Duchamp’s unorthodox works for travel was often a sophisticated affair. He admonished Roché to pack “Why not sneeze Rose Sélavy?” (1921) “so that the weight of the marble doesn’t strain the bars or the base of the cage” when it was to travel to the MoMA’s “Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism,” (December, 1936). (77) On a much more ambitious scale, packing and moving the repaired Large Glass was too important to occur away from Duchamp’s watchful gaze. In September of 1943 he was on hand at Dreier’s home to supervise its transfer to the Museum of Modern Art where it was on loan until 1946. He personally directed the four installers as they crated and moved the piece and then, riding in the truck, gave strict instructions that its speed not exceed fifteen miles per hour. (78) Even so, a few slivers of glass, held only in place by gravity, were jarred out of place. Duchamp later “spent several hours fitting them back where they belonged.” (79) As might be expected, he supervised the removal of the Large Glass from the Museum of Modern Art three years hence (on 1 April 1946) in preparation for its return to Dreier’s home.

When the Large Glass was to be transported for the last time, now to its permanent disposition in the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1952, Duchamp had become the undisputed authority on moving the fragile and unwieldy construction. The arrangements intensified; his communications to director Fiske Kimball reveal anxieties about the move. Duchamp expressed a fitful series of nervous requests and balks. He suggested they wait for good weather before proceeding and, after further thought, cabled Philadelphia suggesting, “Four strong men needed.” (80) Hoping to avoid the kind of damage originally wrought upon the work, a few days later he wired to say that he was “expecting to ride back on [the] truck.” (81) Although he only rode back as far as New York, he appeared in Philadelphia the next day to supervise the unloading. In the end, a relieved Duchamp was able to tell Dreier that the transport of the Large Glass “was a success.” (82) Eventually, under Duchamp’s supervision, the Large Glass would be cemented to the floor of the Philadelphia Museum of Art amidst the Walter and Louise Arensberg Collection. Though this protected the work from further damage, it also meant that the piece could never be exhibited elsewhere. Its immobility is one reason why exacting replicas of the Large Glass had to be made by Richard Hamilton (1966) and Ulf Linde (1961) for the Duchamp retrospectives they were then mounting. Hamilton also reproduced the Glider Containing a Water Mill in Neighboring Metals (1913-15) for the same reason. After years of worrying after the transport of his glass works, Duchamp, in his last years, seemed reluctant to see them move at all. To Hamilton’s queries about possible loans to his lionizing Tate Gallery retrospective (1966), Duchamp said he did not wish that the fragile To Be Looked at… (1918) should travel from the MoMA. (83) Evidently, its safety had become more important than its being looked at.

Duchamp’s anxieties about the condition of his pieces reflected his convictions about posterity and historical reputation. He believed that the physical condition of an artwork had a direct bearing on its place in history, metaphorically equating the endurance of an artwork with the span of a human life. The mortality of artworks lay both in their physical condition and in their historical significance–if a work was not “healthy,” it could not enjoy the “life” of a historical reputation. “Men are mortal, pictures too,” was his aphoristic description of the physical lifetime of a work. (84) Another statement from the same year further developed this notion.

Although Monet’s paintings may have lost some of their original vividness, they have hardly become black. This sort of hyperbole indicates Duchamp’s sensitivity to the conditions of artworks and their prospects for “life” in perpetuity.

Although most artists share Duchamp’s interest in preserving the original state of their pieces, Edgar Degas regarded an artwork’s gradual diminution as a desirable part of its appreciation. When the Louvre cleaned one of its Rembrandt paintings, the artist cried, “Time has to take its course with paintings as with everything else, that’s the beauty of it. A man who touches a picture ought to be deported. To touch a picture! You don’t know what that does to me.” (86) Though moved to conserve his pieces as effectively as possible, Duchamp did acknowledge the inevitability of an artwork’s decline. When Robert Lebel and Robert Dorival were trying to organize a major Duchamp exhibition in Paris, in 1966, they requested the artist solicit the Philadelphia Museum of Art about possible loans of his works. He responded, “Impossible for the glass: the [9] Malic Moulds–they are senile and no longer travel.” (87)

For Duchamp, artworks could “die” altogether, consigning their historical significance to oblivion. In the early 60s, art historian William Seitz asked him about contemporary artists who used unorthodox materials. Seitz was doubtless referring to the aesthetic implications such materials raise. But Duchamp’s answer says much about what he regarded as an artist’s central concern–the material longevity of his works.

Seitz:

It’s interesting that so many artists how work in very perishable materials, such as refuse and old newspapers.

Duchamp:

Yes that’s very interesting. It’s the most revolutionary . . . attitude possible because they know they’re killing themselves. It’s a form of suicide, as artists go; they kill themselves by using perishable materials. They know it will last five years, ten years, and will necessarily be destroyed, destroy itself. (88)

Duchamp’s use of the word “suicide” implies that artworks represent artists’ historical existence. Artists are thus obligated to create works that are physically sound and durable. In ironic reaction to this anxiety, Duchamp once said that one attraction to chess for him was that “at the end of the game you can cancel the painting you are making.” (89)

It may seem surprising that a Dadaist would so insistently recoil at the idea of ephemeral artworks. A commonly held notion about Dada artists is that their nihilism was so pervasive that they and their works somehow self-destructed as a result of a perverse inherent logic. The anti-art attitude of the Dadaists, however, was more theoretical than actual. Gabrielle Buffet-Picabia recalled that, during Arthur Cravan’s notorious drunken speech and strip-tease at the Grand Central Gallery (site of the 1917 American Independents Exhibition), her circle of friends were worried lest Cravan damage a painting that was situated behind him.(90) Perhaps more than most avant-gardists, many Dada artists expressed a heightened interest in conserving their works and gestures for a posterity that would appreciate them. Along these lines, Lucy Lippard finds it ironic that the “ex-Dadas have been more concerned with their own histories than have been the participants in any other major movement.” (91)

click to enlarge

Illustration 5

Tu m‘, 1918, oil on

canvas, bottle brush,three

safety pins, one bolt. Société Anonyme

Collection, Katherine Dreier Bequest,

Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Conn.

Considering Duchamp’s obsessive concern for the condition of his pieces, it is not surprising that he sometimes expressed the theme of conservation directly in some of his works. For instance, he painted a trompe l’oeil tear inTu’m (1918) (See Illustration 5) which he rudely “repaired” by three real safety pins. The hasty, ersatz “repair” suggests that conservation is often a crude compromise. The “tear” is widely regarded as a witty jibe at the preciousness of art. But it also suggests that paintings are fragile things and can sustain horrible damage. The tear, it is important to observe, is only an illusion of damage; perhaps Duchamp could not abide an actual one.

click to enlarge

Illustration 6

Unhappy Ready-made,Boîte en

valise reproduction made by Duchamp

after Suzanne Duchamp-Crotti’s painting,

Le Ready-made malheureux de Marcel

(Paris, 1920).Guido Rossi Collection, Milan.

The title of his Readymade malheureux (Unhappy Readymade) (1919) implies that an artwork’s physical condition is integral to its meaning. It was comprised of a geometry book that he instructed his sister, then living in France, to hang on her porch (See Illustration 6). Predictably, the weather gradually destroyed it. The original idea for the piece was first expressed in a note, later included in The Green Box, in which Duchamp reminded himself to “Make a sick picture or a sick Readymade.” (92) The inspiration for Unhappy Readymade, then, involved the notion of the physical vulnerability of artworks. The Unhappy Readymade is unhappy because it will not endure; it is gradually deteriorating. Insofar as real weather tears the work apart, the piece is a metaphor for the damaging effect of time on art. (93)

Duchamp explored the idea of repair and conservation in 3 Standard Stoppages. (1913/14) (See Illustration 3). He had been inspired by a Paris shop sign, “stoppages et talons,”advertising invisible mending and heel repairs to socks and stockings (et talon, or étalon = “standard”). (94) Mending is, of course, an operation of repair and maintenance. Perhaps the varnished threads in 3 Standard Stoppages, whose shape has determined a new standard of measure, are meant to be read as threads which have become unraveled from an “invisible” mend. Interpreted in this way, what is being conserved in this work (mends) is the evidence of repair, now absurdly made standard in the templates. What makes this doubly preposterous is that the forms that repairs take are wholly contingent on the damage they seek to rectify. This work thus suggests something of the despairing futility of predicting and measuring repair. As mentioned earlier, he completed it in 1936 by cutting the canvases according to the shape of the varnished threads, gluing these to glass plates, and fitting them into a slotted, wooden box. Also included in the box are flat, wooden “templates” (yardsticks, of sorts) whose shapes were determined by threads dropped from a certain height. Thus completed, the format reflected his attempt to conserve the sophisticated documentation of a pataphysical experiment.

click to enlarge

Illustration 7

Network of Stoppages Etalon

, 1914, oil on canvas.

Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Illustration 8

“Fresh Widow”,1920,

miniature window frame, paint,

black leather. Museum of

Modern Art, New York.

The background of a related work, theNetwork of Stoppages Étalon (1914) (SeeIllustration 7), is actually an unfinished version of the painting, Young Man and Girl in Spring (1912), turned on its side. Thus, its very position is a contraversion of the proper handling of art. Its “stoppages,” the little mends, which look like little buttons or stays, create a pattern in accordance with the “damage” which the painting has ostensibly sustained.

“Fresh Widow” (1920) (See Illustration 8) is a miniature, carefully constructed French window that Duchamp commissioned from a carpenter. The piece requires a great deal of maintenance according to the artist’s jesting instructions. Instead of glass panes, it has leather panes that the artist insisted must “be shined every morning like a pair of shoes.” (95) The regular polishing, one assumes, is what keeps the widow/window “fresh.”

Besides their aesthetic implications, and their myriad semantic allusions, many of Duchamp’s readymades involve tools or implements that facilitate maintenance or organization. Bottle dryers, hat racks, urinals, snow shovels, typewriter covers, and so forth, all fall into this category. His notes, too, often describe objects of domestic utility and maintenance. One from the Box of 1914, for instance, exclaims “Long live! clothes and the racquet-press” (96) invoking clothing, a type of outer shell (clothes “make” the man) and the racquet-press, which protects the vulnerable gut strings of the tennis racquet. It appears that, even when he was inventing Dadaistic non-sequiturs, Duchamp tended to conceive of items of utility and conservation.

Decades of repairing and maintaining a (rather modest) oeuvre enabled Duchamp to make elaborate provisions for his posthumously unveiled Étant donnés: 1. la Chute d’eau 2. Le Gaz d’éclairage (Given: 1. The Waterfall 2. The Illuminating Gas) (1946-66). The complete title–all taken from a note reproduced in The Green Box-is a wordy description of the work: “Dismountable approximation executed in New York between 1946 and 1966. By approximation I mean a margin ad libitum [of freedom] in the dismantling and reassembling.” (97) The work had to involve an element of freedom in its reassembling because it would necessarily be done by others. The work is thus described as a new genre, a “dismountable approximation,” its title no longer involving the punning absurdity given to such early works such as The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even. Instead, it alludes to many of Duchamp’s concerns: authorship, chronology, media, genre, and conservation.

click to enlarge

Illustration 9

Interior, Étant donnés:1.

la Chute d’eau 2. Le Gaz d’éclairage

(Given: 1. The Waterfall 2.

The Illuminating Gas), 1946-66, mixed media assemblage.

Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Originally constructed in his New York studios, Given was dismantled and reassembled in the Philadelphia Museum of Art after the artist’s death in 1968 (See Illustration 9). Its conception involved a built-in element of collusion with the museum for its construction and ongoing maintenance. To assist in the reconstruction of the piece, Duchamp composed two lengthy, handwritten notebooks, complemented by Denise Hare’s photographs and by a foldout construction. It is in effect a lengthy, precise instruction manual for assembling the work in his absence and as such is different from his other published material, i.e., The Green Box, the White Box, and so on, which are autonomous objets d’art. Nevertheless, it has wrongly taken its place among these editions, as if it were a densely aestheticized text ripe for decoding. (98) These instructions were specific and unequivocal, not meant to aesthetically enrich the work’s meaning in the manner that theGreen Box does for the Large Glass.

Duchamp advises on the brand of fluorescent lights used (“very white (General Electric) or pinkish”), the number of turns-per-second that the waterfall motor makes, as well as advice to have two people move the nude figure when necessary. Ironic in lieu of its description as an “approximation,” the notebook provides little margin for variance. Made with the knowledge that he would already be dead when the work was unveiled, the notebooks are an astonishing attempt to control the conditions in which his art would be experienced in a remote future.

Duchamp also left specific instructions for art made in connection with Étant Donnés. The small leather and plaster maquette (1948-49) that served as the model for the life-size nude in Étant Donnés bore instructions for its lighting and, if necessary, its restoration; he even made a case to protect the little leather figure. (99)

Mining Duchamp’s advanced art for ever-subtler allusions has directed attention away from his almost fetishistic concern for the physical wellbeing of his pieces. This study reduces some of the conventional distance between Duchamp and his works modifying his prevailing construction as the smirking demiurge who dashes off pieces, heedless of their fate. Conservation was, for him, central to the artistic process. Only artworks in sound condition could be given up to an unmanageable and uncertain future–one in which paintings turn black, glass pieces are reduced to “marmalade,” and one where artists might unwittingly commit art historical suicide.