|

by Ya-Ling

Chen

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

More

Born in Niigata,

Japan, in 1937, Shigeko Kubota grew up in a monastic environment during

the WWII and the subsequent postwar period. She later studied sculpture

in Tokyo in the late 1950s and early 1960s, during which Japan strived

to reestablish it’s financial, political and psychological welfare from

the devastation of the war. This period also offers a break for Japanese artists to move

away from fairly confined notions of presentation and the cultural isolation

from the global art community. Although such avant-garde group as Gutai

began to evoke innovative ideas, for instance, painting by foot, crashing

through papers, throwing paint, or displaying water

Despite the newly raised confusion with regard to the sequence of happening dates between these two events mentioned in the story from which the lovely anecdote on the beginning of their friendship is woven,(3) Duchamp has drawn profound impact on Shigeko Kubota not only he is the inspiring father icon for the Fluxus group and for Kubota’s creative impulses, but also their unforgettable friendship in the final year of Duchamp’s life. Took part in and photographed the Reunion, a chess game organized by John Cage which turned out to be the last public reunion between two masters of the contemporary creative minds,(4) Kubota began to utilize video technology, a novel mean in which dream and reality could meet, and accomplished three works based on this chess event upon which her artist career as a pioneering video artist set forth.

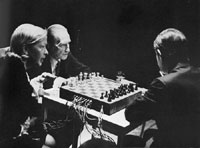

Performed at Ryerson Theatre of Ryerson Polytechnic, Toronto, in March 5 of 1968, Reunion is organized by John Cage with other participants including musicians David Tudor, Gordon Mumma, and David Behrman and the wired-up chessboard designed by Lowell Cross (Fig. 3). When Teeney and Marcel Duchamp taking turn play chess with Cage on the stage, the pre-moduled photoreceptors would serve as a gating mechanism to receive messages of movements and to transmit sound and light. Along the move of the chess pieces, the sound will be cut off or rerouted to generate a kind of random music by means of the pre-moduled chance operation of two "intellectual minds." With those photographs and material acquired later, Kubota slowly developed three works based on this memorable event respectively in the formats of a book, videotape and a video sculpture within a period of time ranging from 1968 to 1975.

Published in 1970 with limited edition of 500 numbered copies in blue cover inserted in a blue cardboard box, Marcel Duchamp and John Cage (Fig. 4) consists of photographs taken in the Reunion performance and a 33 1/3 rpm blue flexidisc (phonograph) of the Reunion sound recording, accompanied by text written by John Cage under the title of "36 Acrostics re. and not re Dcuhamp." The videotape of

1972, carried the same title as does the prior book, is composed of

segments including John Cage telling stories, mediating, playing a piano,

sitting bandaged while Nam June Paik measuring his brain waves (Figs.

5 & 6) , with still images of Teeny,

Duchamp and Cage playing chess in Reunion alternating throughout

as though they are the interlude in music composition. In addition,

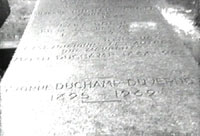

footage taken when Kubota's visit to the Graveyard of Duchamp family

in Rouen, 1972 (Fig. 7)(5),

captures the fleeting movement of wind dancing with the patchy light

that pierces through the shadowy grove. A sense of euphoria generates.

On and off for three times, the exotic and shaman-like voice of Kubota

chanting--"Marcel Duchamp, 1887~1968," is the only sound intervening

with the seemingly timeless silence. The life-death confrontation in

an infinite circle is further reinforced through the repetitive expression.

These footages would later been edited and colored for Kubota's astounding

installation, Marcel Duchamp's Grave (Fig.

8) , at The Kitchen, New York in 1975.

The concluding work, the Video Chess (1968-75) (Fig. 9), a sculptural TV is constructed and posited on the floor with its monitor facing up. A transparent chessboard with transparent chess pieces sit above the TV monitor. Kubota reworked on the 1968 Toronto photographs by having them transferred, keyed, matted, and colorized at the Experimental TV Center in Binghampton, NY with the assistant of Ken Dominik, and later at WNET-TV Lab in New York. The monitor plays the transferred and colorized images of Duchamp and Cage playing chess with the original soundtrack emitting. Every crosspoint of the chess matrix has a hole and light cell, which are modulated by the proceeding of a chess game. As viewerd/players look down/play chess on this transparent chessboard, in Kubota's words, they are "accompanied by the videotape of the two great masters playing from the otherside of this world." (6) Don't In addition to the Toronto event, porta-pack video camera is an integral part for Shigeko Kubota in its capability as a mirror that artist could open up a dialogue with the self they encountered everyday, and the unknown natures they were seeking to uncover. Margot Lovejoy pinpoints the benefit for the presence of the first portable video camera to the art world:

During the 1960s,

the Fluxus' adoption of video into their happening and performance in

Europe and the United States created a different climate of aesthetic

discourses which resulted the wide attraction for young generation to

reflect on video as an effective medium for the new art. The possibility

to commit personal testaments to tape in any environment, however intimate,

and in complete privacy has brought video as an

It is noteworthy that Kubota is used to handle video work herself throughout the process. Herewith, she could gain a total control over what she chose to preserve or erase. Attracted to the video because of its "oriental" and "organic" nature--"like brown rice, brown curb, like seaweed, made in Japan." (11)--the single-channeled TV is capable of bridging two extreme worlds--"it is always somewhere between dream and reality." (12) She later contemplates, "video acts as an extension of the brain's memory cells. Therefore, life with video is like living with two brains, one plastic brain and one organic brain. One's life is inevitably altered. Change will effect even our relationship with death, as video is a living altar. Yes, videotaped death negates death as a simple terminal."(13) the wind-break

became Closely examining these three works, one can tell the apparent contrast between the independence of individual segments seen in the blue book (1968-72) as well as in the videotape (1972), and the integrality of Video Chess (1968-75) as the sculptural entity. In the 1972 videotape of Marcel Duchamp and John Cage, fragments of images alternating with one another, barely has the elaborated trace of editing revealed. In the 1991 interview, Kubota admitted her reluctance to alter the video-recorded images, which is coherent with what we see in the 1972 videotape, an open-ended quality register with a sense of naivety. On the contrary, Video Chess is eloquently constructed and presented under an authoritative art form. This time, Kubota ruminates on the overall presentation as a whole other than the co-existing fragments presented in the prior video work of Marcel Duchamp and John cage. The conceptual connection is reinforced by the absence of both intellectual minds. In other words, the absence of both Cage and Duchamp has turned into an abstract physicality. The spectator can only aware of their presence by the arbitrary appropriation offered by Shigeko Kubota. It as if she is the invisible and all-powerful shaman who channels and embodies the men-objects with our living world in a simulated territory where life and death negates each other, turning into an endless circle.

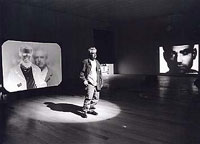

In her visit to Duchamp's grave, the ritual act of presenting offering (her blue book) on the grave and chanting is "as in the oriental family custom of putting rice cookies on the dead ancestor's altar." (15)Usually performed by certain official in ancient culture, chanting during the funeral rite is regarded as the emotional mourning toward the lost of loved ones and to communicate with them in the otherside of the world. Aesthetically, the poetic and exquisite elaboration of Video Chess is quiet appealing from which Kubota would further mature herself as an original and independent Video artist and to account as a significant figure among her peers, such as Nam June Paik(Fig. 11), Peter Campus (Fig. 12), Bill Viola (Fig. 13), Gary Hill, and Dan Graham, who together mark the primal phase of the Video Art. However, not so muchas merely to deduce the conceptual connection between Kubota's Japanese and Duchampian "roots," (16) her ability to integrate personal memories and history into an exquisite sensibility substantiates Kubota's identity as a female artist who tackles on motif rooted in art and life, and elevates it onto much elevated concerns with the hegemonic discourse of art history. To Kubota, art making is always something deeply associated with life. In the case of these three works derived from the chess Reunion, the materialization of Duchamp and Cage is appropriated and repeated by Kubota. Thus, the strive to seek for the truthful perceptions of history will be best summed up by Kubota's self-description for her 1991 video sculpture Adam and Eve, "an appropriation of an appropriation of an appropriation of an appropriation." From this perspective, the division between subject/object has been erased which no longer hold authenticity but the repetition of the past.

Notes

Figs.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||