Between Music and the Machine: Francis Picabia and the End of Abstraction by

Roger I. Rothman |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

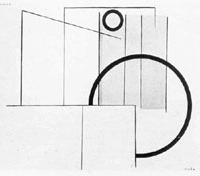

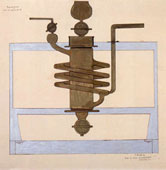

It is impossible to overlook the transformation that took place in such a brief span of time. In early 1914, Picabia was fully committed to exploring the language and ambition of abstract painting; in early 1915 Picabia had turned himself completely around. In adopting the machine and its metaphorical potential, he had returned to the language of representation, to the depiction of things in the world. He had abandoned almost every trace of the concerns--in terms of both form and content--that guided him just a year before. Where the works from 1913/1914 were abstract, organic, painterly, rich with coloristic complexities, and suggestive of interiorized, subjective states of mind, the works from 1915 were largely monochromatic, linear, inorganic, and clearly derived from and reflective of real-world objects. Almost every scholar to have approached this shift has endeavored to highlight its radicality. The break was total and unequivocal, self-evidently so. Michel Sanouillet summed it up most succinctly when he described Picabia as having "turned his back" (8) on modernist painting, abandoning its procedures and promises in favor of a poetics of modernity--one evidently influenced by the example set by Duchamp. As de Zayas was to put it with reference to Picabia's Spanish origin: "He is the only one who has done as did Cortez. He has burned his ship behind him." (9) And yet to follow

the painter's work beyond 1913 is to recognize that the break was in

fact far from absolute. For one, Picabia never really gave up his commitment

to abstraction. Works like Fantasy (Fig. 11)

and Music is like Painting (Fig. 12),

both of which were painted at the same time as the mechanomorphs, attest

to Picabia's persistent commitment to the procedures and ambitions of

abstraction. And there is no doubt that this was a commitment that would

erupt here and there throughout the late teens and into the early twenties

(Lausanne Abstract, 1918 (Fig. 13);

Streamers, 1919 (Fig. 14); Coils,

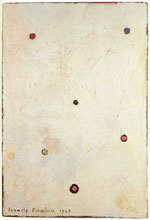

1922 (Fig. 15)), and although the twenties

and thirties were dominated by a variety of figurative works, abstraction

would appear again in the forties (Painting of a Better Future,

1945 (Fig. 16) ; Playing Card, 1949(Fig.

17) ). And this is to say that even at first glance, Picabia's

case is quite unlike that of Duchamp. Abstraction, that "word

he invented," would remain throughout Picabia's life a palpable

presence, inflecting almost all of his work, even, if not especially,

the mechanomorphs.

This should be obvious, given the way in which all of the New York mechanomorphs retain, even reinforce, a modernist commitment to the integrity of the picture plane (its flatness and boundedness), as well as in the way in which the bulk of the mechanomorphs, like the earlier abstractions, resist interpretation as real-world objects. In Paroxysm of Sorrow (Paroxyme (sic) de la douleur) (1915) (Fig. 18), for example, the uniform application of paint, the nesting of rectangular forms (the largest of which coincides with the outer limit of the canvas), as well as the work's aggressive frontality and symmetry suggest a continued dialog with the language of abstraction, in particular with the shallow space, central organization, and largely symmetrical, well-framed composition of Udnie. And this is no less true of A Machine Without a Name (Fig. 19) where the flatness of the picture plane is asserted unequivocally, not by virtue of an unmodulated application of paint and the web of vertical and horizontal lines. Indeed, its title seems to demand that we understand the painting as thematizing the a-signifying ambition of abstract painting. Perhaps, then, we ought to consider not only de Zayas' account of Picabia (the Cortez of the avant-garde), but also that of Buffet. For as she understood it, her husband's work, from 1907 on, was on some level engaged with the discourse of the "painterly." (10) Indeed, it was this above all that in her mind distinguished the work of Picabia from that of Duchamp. So if we are to take Buffet seriously--and even the most cursory glance at Picabia's work suggests that we would not be wrong to do so--then we ought to consider the possibility that the mechanomorphs, coming as they did on the heels of an extended investigation of the possibilities of abstraction, were themselves still invested in, or responding in some manner to the promise of modernist painting--the promise, as Picabia described it, of "expressing the purest part of the abstract reality." (11) The Music of Painting

Picabia had just returned to Paris when he scrawled this note on a postcard-size sheet of paper and sent it to Stieglitz. Following up on the implications of his New York watercolors, he began work on the large oil-paintings, Udnie and Edtaonisl, both of which were later shown at the Salon d'Automne. (13) It has since been demonstrated that both titles, although apparently nonsense words, were the result of a series of selections, contraction and reorganization, such that the word "Udnie" was derived from "Uni-dimensionnel" and "Edtaonisl" from "Étiole danseuse." (14) What remained was a pair of words that relinquished their once-signifying logic for the sake of pure sound, freed from the communicative function of language. (15) As titles to abstract paintings, they do indeed serve as "names in rapport with the pictorial expression," and as such lend support to the viewer's inclination to consider the painting not as a representation of something, but as itself a something--that we are not looking at a picture of Udnie, but Udnie itself. While Picabia's note to Stieglitz is clipped and somewhat vague, it must have been comprehensible to the photographer if only because of his familiarity with the long and quite detailed account that Picabia gave to Stieglitz during his exhibition of abstract watercolors. (16) Picabia's central argument sets out on common territory, articulating a pictorial practice aimed, like much of modernist painting at large, at communicating one's "deepest contact… with nature," a task for which traditional illusionistic techniques are clearly inadequate:

In this, Picabia is merely recapitulating arguments set out in support of cubist painting, in particular the Puteaux cubism of Gleizes and Metzinger, with whom Picabia was close in the years leading up to his first trip to New York. As the two put it in Du Cubisme, the task of the cubist painter is to "depart from superficial reality" so as to capture the "profound reality… concealed in the most commonplace objects." (17) We could well imagine that Picabia would continue in this vein, arguing for a painting of the reality beyond appearance, the painting of a more profound reality than the one we see with our eyes alone. And yet Picabia shifts gears at this point, without warning or justification, from the representation of nature to the representation of inner consciousness:

And this, we find, is a necessary slippage, because what Picabia really wants to get at is the way in which painting can follow the example of music so as to abandon the task of representation altogether. In sliding from nature to consciousness, Picabia moves one step closer to the painting of form and color alone:

I have moved rather slowly through this text because it serves to illuminate, especially in its slippages and distortions, the means by which Picabia came to understand his break with the cubist logic--still representational at bottom--for the sake of a painting that would justify itself by virtue of its commitment to "form and color in itself." (19) Of course, the justification of advanced painting by way of an analogy to music was in no way unique at that moment. But what was unique was the specific nature of his appeal, one that derived in large measure from the example set by his wife, herself a student of advanced musical discourse, both in France and Germany. When Buffet first met Picabia in the winter of 1908, she was on holiday from her musical studies in Berlin. Having completed her studies under Vincent d'Indy at the Schola Cantorum she went to Germany where she met up with fellow student, Edgar Varèse. For Buffet, as for Varèse, the most significant musical influence at that time was the work of the pianist, composer, and theorist Ferruccio Busoni. (20) In fact, the two were so committed to Busoni's ambitions that they went so far as to build some of the new musical instruments that Busoni had proposed as a way out of traditional tonality. (21) But it was Busoni's theoretical work rather than his inventions that had the greatest impact on Buffet. (22) Through Busoni, Buffet developed a highly sophisticated account of the state of avant-garde music, an account that was in turn passed on to Picabia. (23) Busoni published Sketch of a New Aesthetic of Music, his most ambitious attempt to reconsider the structure and aims of advanced music, in 1907. (24) At stake here was the attempt to draw music as close as possible to "nature herself." Not to represent nature, but to be nature. In this, Busoni imagined a kind of musical composition that would live and grow as any natural organism--music as a body of sorts, self-organizing and self-contained, a music guided by "natural necessity," following "its own proper mode of growth." (25) What made Busoni's Sketch so radical was the way in which it articulated an alternative to what was at the time the two dominant models of musical composition, so-called "absolute" and "program" music. Absolute music, as it was commonly understood at the time, was based upon the manipulation of the tonal, harmonic, and architectonic conventions of musical composition as they had developed over the course of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Program music, by contrast, was explicitly representational and concerned the use of musical form to suggest events, things, feelings, etc. Its place was in the theater, as it was used to underscore the actions performed by players on the stage. Busoni considered both forms equally impoverished: program music for its utter triviality, its reduction of the lofty art of music to the level of simple imitation--the sounds of thunder, the march of a military regiment, the plaintive cry of the dying heroine (26) ; absolute music for its uncritical acceptance of the given conventions, its inconsequential formalism. (27) Both program and absolute music were hopelessly conventional, and as such of no use to the composer with ambitions of a music of nature at its most profound. It was with this insistence upon the elimination of convention that Busoni faced the problem around which the entire essay turns: insofar as music is to avoid falling into complete "formlessness," (28) it must establish for itself a certain self-generated system within which to coordinate itself. On the other hand, to perpetuate such a system beyond a single instance is to fall back on convention--a new convention, of course, but a convention just the same. Busoni's attention to the problems of conventionalization went so far as to include the very act of notation, for as he saw it: "the instant the pen seizes it, the idea loses its original form. The very intention to write down the idea, compels a choice of measure and key." (29) And it is from this recognition of the inescapably conventional nature of all music, even music at its most self-consciously anti-conventional, that Busoni was drawn to conclude his essay with a long quotation from Hugo von Hoffmannsthal:

Hoffmannsthal's remark serves to underscore what may be the most radical proposition in Busoni's text (a proposition that would have to wait until 1952 for its performative realization (31)): if it is the case that music draws closer to nature the more completely it abandons the given conventions of musicality, and insofar as this movement pushes the work of art toward the conditions of non-communication (of a language that even the author cannot understand), then one would have to admit that even the brief moment of silence that separates the performance of one movement from the next is "in itself music." (32) What Busoni is left with is therefore a music divided in two: on the one had, the fullness of a sound that eludes the comprehension of the composer himself, and on the other, the total evacuation of all sound. And this is to say that the insistent pursuit of a non-conventional, fully organic and self-generating work of art leads, at its limit, to either the utterly formless or the entirely vacant. >>Next Notes

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||