|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Transformation

and Tradition: by Lauren Wilcox

Sanford Biggers, 31, is an artist who recently located to New York City after living in several cities in the U.S. as well as around the world. His work provides a repertoire of concepts amassed, as his use of objects representing power, cultural signatures, and the adoption of several Dadaist aspects and African traditions are components for pieces and performances that pose questions to contemporary society, giving continual examples of the transformation of the mundane into the remarkable. Intrigued by his close relationship with Dada concepts and aesthetics, I was particularly curious to learn all that Sanford Biggers had to tell about his performance, Duchamp in the Congo (Suburban Invasion), which involved two pieces of artwork, one bearing the same name as the performance, Duchamp in the Congo, and another entitled Hangman's House.

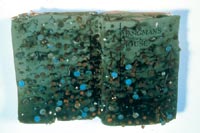

Hangman's

House, a hardcover book inundated with nails on the outside that

pierce through to the inside, was the first to be made. The only readable

text visible through the nails is the titleof the book, which bears

the same title as the piece, Hangman's House (Fig.

1) (United States: New York: Century, 1926 and United Kingdom:

London: Sampson Low, Marston, 1926). While the nails interrupt any

hope of reading the book at first glance, the display is set up in

such a way that some reading is possible from the underside. It includes

a bookstand, which spreads the book open to exhibit the piece in its

entirety. It rests on plexi-glass and a mirror underneath it reveals

part of the text between the pertruding nails. Both pieces are an attempt to reclaim the past--they impel the influence of African art on modern art when artists typically looked at African and indigenous work from Asia and pre-Columbian work to gather ideas to create what would be considered "modern." Each is a vehicle for the journey through modern art from our current post-modern society perspective, rendering the African root of modernist work, allowing the idea of modernism to implode on itself by traveling backwards to so-called "primitivism." The wheel included in Duchamp in the Congo serves as a reference to Duchamp's bicycle wheel:

The title Duchamp in the Congo (Suburban Invasion) depicts the vision of the fictitious trip that Marcel Duchamp took to the Congo to study African works of art and then create an nkisi (nail figure) influenced or nail inundated wheel. To further understand the significance of the execution of Duchamp in the Congo (Suburban Invasion), it is important to note the African tradition associated with the captivity of spirits and their power (minkisi plural, or nkisi singular) into objects. Typically, nail figures, or nkisi n'kondi, carved by some of the indigenous people within the boundaries of the Congo (previously Zaire)(Figs. 3 and 4), symbolize the accordance of a group of people and a collective oath they take, initiated by the driving of the nails or iron objects into a power object to preserve its power.

Biggers explains, "before a ceremony, ritual or some celebratory act that the whole community is involved in, people walk by the sculpture or image and pound nails, shards of glass, and sharp or reflective object into the piece. The piece becomes a power object not only by the veneration that this group of people put on the piece, but the physical activity of pounding and hammering into the piece. Later, the piece itself acts almost as a type of scarecrow to ward off enemies, evil spirits and people who do harm to that group of people. So in the case of the Hangman's House, I used that as an aesthetic metaphor for banishing the history of America, being the Hangman's House, the house of so much lynching. In terms of Duchamp in the Congo, I was using the nails to go against the notion of modernism and primitivism, so in this case instead of warding off physical spirits or enemies, there is a warding off in the psychological or philosophical sense of erroneous notions and traces of modernism, primitivism, and post-modernism." The decision to perform Duchamp in the Congo (Suburban Invasion) during rush hour also played a significant role in the execution of the project. Biggers explains that at that point he obtained what only looked like power objects--the next step involved an actual ritual or some type of physical activity. This activity involved the display of Duchamp in the Congo and Hangman's House in the suburbs of Illinois. Dressed in a suit and tie, Biggers eats breakfast in a diner teeming with other businessmen, holding their briefcases and their newspapers, while Biggers clings to his own spiky, nailed wood "briefcase." Hangman's House, sprouting nails, is Biggers' "newspaper"--an intervention and invasion of the suburbs. The documentation shows Biggers riding on a train and the responses he receives. People look at him inquisitively. He especially recalls standing on a corner in downtown Chicago where another man behind him, briefcase and newspaper in hand, gives him curious looks as if to confront him. These responses seem indicative that the utmost confrontation is the challenge Biggers proposes to commonly held but specious ideas through his performance. He elaborates that the decision to perform during rush hour in our contemporary society was motivated by inquiries into how his power objects can be used, what they mean, and how people respond to them. When asked about the role Marcel Duchamp has played for his work as a whole, Biggers expresses several conceptual similarities between his work and Duchamp's. He starts by expressing that while Duchamp's work is aesthetically and formally pleasing, it was controversial for its time and opposed the conventions of several artists during its manifestation in the Dada period. Biggers relates this to his work: "I also follow the idea of keeping the form as one of the most important elements but also feel strongly about challenging prescribed notions in art theory. The fact that I am the creator or author of these pieces also adds to how these pieces are interpreted by art theory. In that respect, I think it follows that Duchamp's Dada approach is to juxtapose objects and concepts with the norm." Both Biggers and Duchamp use several conceptual layers and elements, sometimes obscure in nature, subtle, or reliant on mechanics, motion, or other involved interaction with their projects to convey ideas. Biggers

collaborated with another artist, David Ellis, for a break dancing

mat project, Mandala of the B-Bodhisattva II, 2000.(Figs.

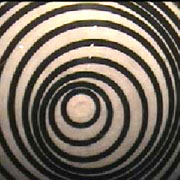

5 and 6) Ellis focused on preserving the idea of Duchamp's

Rotoreliefs of 1935, six

double-sided optical disks made after prior experiments with optics

such as, Disks Bearing Spirals of 1923 (Fig.

7)or Rotary Demisphere (Precision Optics) of 1925.(Fig.

8) Each one of the Rotoreliefs bears a spiral,

eccentric-circle, or similar design. When placed on a record player

or other spinning circle, the Rotoreliefs create an optical

illusion of depth, intensified when looking with one eye rather than

two. Biggers explains, "my approach had to do more with the

Mandala, so there was an overlap there in terms of the circle-based

art form, but for me the Rotorelief was not used as literally

as in Ellis' work. However, the motive was to use the concept on

a more geometrical level with the juxtaposition of circles as well

as other geometries to create the illusion of moment. To enhance this

effect, the dancers create the movement as opposed to a turntable's

rotation."

"One reason we worked on this project together was because I have a fascination with the Mandala and Ellis has a fascination with the Rotorelief for conceptual and aesthetic reasons. We have both been DJs and are deeply into preserving hip hop culture. For us it was the idea of spinning and turning more importantly than the Mandala or the Rotorelief, but these were ways for us to deal with the idea of the spin--the backspin, the spin of a skateboard wheel, or the spin of the turntable--and finding a graphic representation of that idea. The spin is also important in that it goes back to several traditions--whirling dervishes and other dancers going into trance, in Yoruba and Vodoun ceremonies. This reminds me of an interesting fact about the Mandala--sometimes monks don't actually draw or depict the Mandala, but they remember the patterns and then dance and jump in circles to form it with their own motions. We know the trace and graphic depiction of the Mandala and the Rotorelief, but I thought it was interesting to explore how to experience or create the snese of movement the actual depiction." I notice that one of the books Biggers recommends for this issue's Bookstore section is They Came Before Columbus. In a review I read regarding the PS1 show at New York's Clocktower last year, I remember one of the artists, David Godbold, did a cynical piece about the Mayflower, using a comic-like motif against a traditional piece. His installation, entitled America[s] Disclosed 2000, is a wall painting that portrays the initial discovery of America by the Europeans as erroneous. This idea also plays largely into Biggers' work as a whole. He expresses that Godbold's piece "looks at colonialism, dispelling the belief of Manifest destiny, the grand romanticism of colonialism and the current reality of post-colonialism both here in America and Cuba as well as the relationships between sovereign and colonial nations and the people that they colonize. My work touches on the colonial an post-colonial history of the African Diaspora, however, I use Africa more as a metaphor for African America, and not the other way around. It also relates to what we mentioned of art theory and that being a type of colonial mentality." For my last question, I inquire about the connections between Duchamp's ready-mades along with their representation in terms of mass-produced objects and Biggers' work. I wondered specifically if the display of power in them given by their mass production in terms of consumerism and Duchamp's use of them to broaden the definition as well as accessibility of art related to Biggers' use of objects to explore issues of class and race. Biggers replies that although he was trained as a painter, he began to take more interest in making three-dimensional objects. He describes that one of the things drawing him to this decision was the realization that while he tried to depict things by painting them, objects that he would find on the street often already said what he intended to create. "It isn't about depicting--it's about seeing authenticity right in front of you." Biggers goes on…"'Use patina,' the way the paint falls off, the way a chair is rubbed on the arms because someone kept sitting in the chair in the same way overtime, molding the chair itself: it serves as a quiet tribute to history. Different areas where I would find materials, like a poor neighborhood in Baltimore versus an upper class neighborhood in Japan, said different things. I started to find out what areas had different items to collect. I could find a piano for example, in one part of town, where somebody might just throw that kind of thing out. A physical mapping of a various cities began to emerge based on the artifacts I found in certain neighborhoods. I have used this approach in several countries and it gave me aninto the social geography of any givenregion. I was original drawn to objects that were used by individuals and later become interested in mass produced materials that were used by many people. For example, the color tiles that are used in the Mandalas are the same tiles used on the subway and bus floor of Blooklyn, Harlem, and most of Inner-City U.S.A. .." In his work Biggers proposes to us the collaboration of the mundane and sublime, the transformation of visual perception, tradition, and allegories, which are made manifest in the exposure of historical testimony, tradition and acculturation.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||