Duchamp & Androgyny: The Concept and its Context

(Author’s note: The following article consists of the first three chapters of the forthcoming Duchamp & Androgyny: Art, Gender, & Metaphysics. For further information, please contact: lgraham@csuhayward.edu)

The Artist & The Androgyne

click to enlarge

Figure 2

Marcel Duchamp, Nude

Descending A Staircase, No. 2, 1912

Figure 3

Marcel Duchamp, L.H.O.O.Q.,1919

Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) is best known for a painting called Nude Descending a Staircase of 1912, a painting that helped to introduce Modern Art to New York with a bang in 1913. (Fig. 2)Almost as famous is his humorous act of putting a mustache and goatee on a reproduction of Leonardo’s Mona Lisa in 1919. (Fig. 3)

Duchamp is widely thought of as the “Daddy of Dada,” as that movement developed during World War I, and as the “Grandpa of Pop,” as Pop Art developed during the 1950s and 1960s, as well as the “Conceiver of Conceptual Art.” He was all that and more. During the first half of the twentieth century, Picasso and Matisse usually were thought of as the most influential “Artists of the Century.” That evaluation has now changed. Looking back over the last hundred years as a whole, Duchamp now is widely regarded as the most influential artist of the century.

With remarkable spontaneity and seemingly effortless ease, he put forth a lifelong series of revolutionary objects and attitudes including a remarkable non-attachment to fame or fortune. His modesty astonished everyone who knew him, while his ideas have inspired countless artists. Duchamp’s influence, which started during the period of Dada & Surrealism, continued to grow during the Abstract Expressionist era of Pollock and de Kooning and the Neo-Dada era of Johns and Rauschenberg. It is often said that there are few major artists of the last fifty years who were not influenced by Duchamp in one way or another. His influence continues to expand in ever widening waves around the world today.

He gave new status to artists by saying art is whatever an artist says is art, not what critics say art is. In a world that had come to rely too much on reason, he emphasized the intuitive side of our brain by his explorations of chance and open-endedness, an open-endedness that said the viewer is the co-creator of every work of art. In short, he democratized art in a new way.

Duchamp also was fascinated by science, especially electromagnetism. What electromagnetic energy is, and how it moves through our bodies and throughout the universe, occupied much of his thinking. Any number of his works bring together left-brain science with right-brain visualizations, not as scientific statements but as playful parodies of science.

click to enlarge

Figure 4

Marcel Duchamp, The Bride

Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors,

Even, 1915-1923

In another famous work called The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even, (Fig. 4) 1915-1923 (or “The Large Glass,” as it came to be called), the Bride and the Bachelors are divided and never touch, yet they are connected by “wireless” energy. He later used telephone lines to symbolize this flowing of love-energy back and forth, and reminded us that people, not communication systems, are the real “media.”

He grew tired of art that appeals only to the eye, and worked to elevate contemporary art above the merely visual and physical to the level of the metaphysical. His philosophical statements are among the most profound in the history of art.

Nevertheless, his verbal and visual statements often are surrounded and penetrated by humor. His wisdom comes wrapped in a smile. By using a good many words with his images, and by leaving meanings open-ended, he required that we think and feel at the same time. There was method to this left-brain/right-brain approach to experience.

He based much of his work on the ideal of Androgyny (true male-female balance). Bringing together within ourselves the so-called “male” capacity to be rational and the so-called “female” capacity to be intuitive is the stated goal of the meditative traditions within Taoism, Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism, Islam, and Christianity. This dynamic harmony is said to be a key to Enlightenment.

Enlightenment (as they understood it) became the objective of many modern artists in their non-religious quest for wholeness, their secular search for the sacred. However, few if any were able to attain this ideal. Various kinds of self-centeredness got in the way. Duchamp was not without shortcomings (especially in his early years) and may not have attained total selflessness, but he seems to have come closer than most. Whatever his limitations, Duchamp was widely regarded by major artists on both sides of the Atlantic ocean as a highly “evolved” human being – perhaps not fully enlightened, but more so than anyone else they were likely to meet.

In place of the usual (and often egocentric) insistence on self-expression in art, Duchamp pointed out that self-centeredness can be removed from the artistic process, or at least moved off-center. With his “ready-mades” (anonymous manufactured objects he selected and signed), he generated the idea of art-without-artists, and thus opened even further the opportunity for image-making to everyone. Selecting, he said, is a creative act. Moreover, by often replicating his earlier works as editions of multiples, his concept of “self” moved even further away from the object and opened out toward the not-self. The unification of self and not-self is the aim of traditional metaphysical philosophy.

While emphasizing concepts and deprecating the “retinal,” he never lost respect for well-crafted quality. His objects were made with loving care, as were his relationships with others. Duchamp celebrated human nature in general and the erotic impulse in particular, advising above all loving and being loved. He also thought of the relationship between art and life as a kind of oneness. And all along the way he recommended laughter.

Many books and exhibition catalogues have been devoted to Duchamp. Some think there is nothing more to be said. However, there are neglected areas, for example, his metaphysical philosophy. In part, this is because formalist art history, which dominated most of the twentienth century, had no interest in metaphysics. As a rule, the philosophy of artists has been studied only by post-formalist art historians in recent decades.

This book is an exploration of the metaphysical realm of Duchamp’s thought. At the core of this exploration is an analysis of the symbolism of “androgyny.” Why? Because, as I hope to demonstrate, this underexplored theme was central to his work from the 1910s to the 1960s, and was a direct expression of his metaphysical thinking.

What is the meaning of “androgyny”? Several quite different definitions of “androgyny” are in use today. The most superficial definitions have been popularized by Hollywood films, where the term usually refers to “women who act like men,” or “men who dress like women,” or someone whose physical features make it unclear whether that person is male or female. A less superficial use of the term is used in the gay and lesbian community where people often call themselves “androgynes,” feeling a special kinship with the ancient Greek world where homosexuality was common and considered natural.

The modern term “androgyne” comes from the Greek language and combines words meaning man [andros] and woman [gune]. Many gay, lesbian, bisexual, and intersexual people celebrate a psychology which combines elements usually thought of as male with elements usually thought of as female.

In biology and botany, “androgyny” identifies plants and animals who have the capacity to change sex or to fertilize themselves. In the medical community, the term “androgyny” is used for people who are born with ambiguous genitalia, or (in very rare instances) are born with both a sexually functional penis and a sexually functional vagina. More often than not, such intersexual individuals are called hermaphrodites.

“Hermaphrodite” is another Greek term that combines the name of the god Hermes with the name of the goddess Aphrodite. It is an oddity of history that the Greeks worshipped deities who were double-sexed, as did many people around the world. However, if a Greek child was born with double genitalia s/he was killed as a monster.

There is another definition of “androgyny,” one that is much older than any of those in common use today, one that is not even found in most dictionaries. This metaphysical definition is even older than the civilizations of Greece and Egypt. It goes back to the Stone Age, but seldom is discussed in scholarship today except by historians of mythology and religion.

The great World Religions of today usually are identified as Taoism, Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. All of them have some of their roots in the spiritual traditions of our Stone Age ancestors who, for thousands of years, venerated the Androgyne as a deity. The public (or exoteric) doctrines and rituals of today’s World Religions usually make no reference to the Androgyne or Androgyny. However, the ancient Androgyne has endured as the image of a spiritual goal in the contemplative (or esoteric) teachings of all these religions–teachings traditionally available only in monastic settings for people who have made a total commitment to self-transformation in order to be greater service to the world.

Everyone interested in comparative religion is familiar with the symbolism of Yin-Yang in Taoism, Shiva-Shakti in Hinduism, Yab-Yum in Tibetan Buddhism, etc. These unusual symbols of oneness/two-ness are not limited to Asian religions. All World Religions symbolize themselves with visual forms that have a double structure. Consider the double triangle of Judaism, the star & crescent of Islam, and the horizontal & vertical elements of the Christian Cross.

As with all mythological symbols, there are many levels of symbolism associated with these images of what might be described as bi-singularity. Among the most commonly discussed are the relationships between the tribe and the transcendent, between the individual and the divine, between male and female, between active and receptive, between spirit and matter, etc.

Among historians of sacred symbolism, it is widely accepted that these images symbolize both the appearance of duality (to ordinary ways of looking) and the larger truth of nonduality – the ultimate cosmic unity of all reality. In short, these double-images of nonduality represent a basic metaphysical teaching: what may seem to be two-ness actually is oneness when seen from a higher level of perception.

There are a handful of symbols that have been used in World Religions for many centuries to represent universal unity. One of the best known is the image of the circle-square usually called a “Mandala,” from the Sanskrit term for sacred circle or sacred space. Generally speaking, the square stands for matter, or the material world of forms, while the circle stands for the infinite spirit that surrounds and permeates all forms. Less widely known is the traditional image of the Androgyne in which maleness and femaleness are combined in a single human figure. In the traditional literature, the term Androgyne is capitalized because of its transcendent meaning. So it will be in this book when that specific meaning is intended.

While the Mandala image represents a condition, the condition of cosmic unity, the Androgyne image represents one who has continuous awareness of this unity and therefore is said to have “cosmic consciousness.” In the public art of Taoism, Hinduism, and Buddhism, for example, Androgynous deities often are shown as part male & part female. In the esoteric art of these traditions, the teaching is that not only deities but human beings can have this transcendent consciousness. Illustrations of traditional Androgyne art appear in Chapter Two. A bibliography of the comparatively new field of Androgyny Studies is at the end of this book.

A rounded view of this primal meaning of Androgyny, and how Duchamp used his understanding of that meaning in his work, is the subject of this book. Our point of departure is a conversation I had with Duchamp when I was a young curator at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Here is part of what was said:

|

LG:

|

May we call your perspective Alchemical? |

|

MD:

|

We may. It is an Alchemical understanding. But don’t stop there! If we do, some will think I’ll be trying to turn lead into gold back in the kitchen [laughing]. Alchemy is a kind of philosophy, a kind of thinking that leads to a way of understanding. We may also call this perspective Tantric (as Brancusi would say), or (as you like to say) Perennial. The Androgyne is not limited to any one religion or philosophy. The symbol is universal. The Androgyne is above philosophy. If one has become the Androgyne one no longer has a need for philosophy. (1) |

Androgyny & Perennial Philosophy

|

“It is essential…to undertake the reconstruction of the primordial – – André Breton, On Surrealism in its Living Works (1953) |

Duchamp was so full of humor that many overlook how philosophical he also was. When asked what adjective would best describe his work, Duchamp replied: “metaphysical if any.”(2) From an early period, his primary purpose seems to have been first to find the transcendent, and then, as an artist, to suggest the transcendent realities of metaphysical truth. He phrased his transcendental goal in various ways. For example, “…art is an outlet toward regions which are not ruled by time and space.”(3) He later said: “…the artist acts like a mediumistic being who, from the labyrinth beyond time and space, seeks his way out to a clearing.”(4)

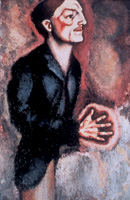

click to enlarge

Figure 5

Marcel Duchamp,Portrait

of Dr. Dumouchel, 1910

One of the earliest indications of Duchamp’s interest in the esoteric was his 1910 portrait of his friend, Dr. Dumouchel, showing an aura around his body, an aura that is particularly luminous around his healing hands(Fig. 5). How Duchamp came to be interested in esoteric ideas is unclear. Might it have have been after reading some books about Theosophy or Alchemy? Perhaps. The subject requires further study. However his interest in metaphysics began, that interest obviously was strong about 1910-11 when his art was moving from Fauvism toward Cubism and beyond. While Duchamp was not interested in metaphysical systems, he was very interested in metaphysical thinking – the kind of thinking that moves the mind beyond duality towards what he described as “regions which are not ruled by time and space.”

His way of thinking about metaphysical symbols was not part of a system but does parallel what is known as Perennial Philosophy. Perennial Philosophy is so called because it seems to have been present for as long as there has been philosophy, and because it has continued to appear century after century in Taoism, Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.(5) All these traditions have their own uniqueness. Many of their public or exoteric beliefs are different from one another. Nevertheless, students of comparative religion have found that there is a body of esoteric beliefs that is common to all of them. This common core of understanding is now widely known as Perennial Philosophy. Here is a concise summary:

Beneath, beyond, around, and through all manifested reality is an invisible reality that is formless. It also is infinite, eternal, luminous, and loving. In Western traditions, this is often called the Ground-of-Being, or Unconditioned Consciousness. As a rule, only a few are aware of this transcendent reality continuously. Ordinary egocentricity prevents the possibility of such awareness. Most people suffer all through life because they are bound within a self-referential psychology. This prison of the ego, this shell of selfishness, also prevents people from understanding what life can be like if one is ego-free, free to be world-centered rather than self-centered, free to be all-loving rather than loving only one’s self. Selfish desires condition consciousness and cause constant suffering. There are many ways to break through this egocentric shell and begin to “glimpse light through the cracks.” Every tradition has its own methods.

Enlightenment or Illumination are names given to breaking through to a higher level of awareness. Breaking through, it is said, often takes place slowly, gradually, in painful stages. In the language of Tantric Hinduism and Tantric Buddhism, one moves up through chakras to higher levels of awareness. There are parallel stages of development in Christian Alchemy and Jewish Kabbalah.

Semi-Enlightened stages include proto-Androgynous awareness of dualities reconciling, of male and female elements uniting. In Alchemy what results from this Mystic Marriage is the Androgyne whose Golden Consciousness transforms life. Is the situation similar in yoga? Mircea Eliade reports that it is: “The union of the divine pair within his own body transforms the yogi into [an] ‘androgyne’.” (6)

How old are such teachings in the West? Certainly there was Androgynous thinking in early Christianity, long before medieval Alchemists focused on the image of the Androgyne. In one of Paul’s letters in the New Testament he states that, after Baptism, “There is neither… male nor female, for ye are all one in Jesus Christ.”(7) According to another early Christian document, the Second Epistle of Clement, when Jesus was asked at what moment the Kingdom of Heaven would come, the answer was: “When the two shall be one, the outside like the inside, the male with the female neither male nor female.”(8) Probably even older is the Jewish oral tradition recorded in the Zohar of the Kabbalah: “It behooves a man to be ‘male and female’ always….”(9) It would be a mistake to think Androgyny is only an old ideal; its reality is very much alive. Consider, for example, this testimony from the contemporary Chinese Zen master Chuan Yuan Shakya. She recently reported: “Zen masters treat any monk who attains androgyny as if he were truly royal.”(10)

The Perennial Traditions teach that even higher levels of consciousness exist beyond Androgyny. To suggest the nature of the “beyond” there is a special metaphor in Zen. Enlightenment or Satori is described as “entering the stream.” At a higher stage one “becomes the water.” The first step towards transcending the Little Self, and attaining totally fluid consciousness, is realizing there is more to life than the realm of the senses, the realm of self-satisfaction, the realm of space and time. Beyond space and time, where rational analysis and sense perceptions work, is the realm of eternity. According to Perennial Philosophy, eternity is not a long time; eternity is beyond time. Illuminated awareness is said to take place when time and timelessness are linked permanently, when the finite and the infinite always are perceived as aspects of each other continuously commingling, when the world and Nothingness are one.

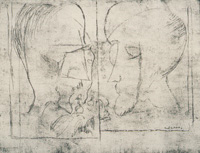

click to enlarge

Figure 6

Marcel Duchamp, The Chess Players,

etching of 1965, after

a drawing of 1911

Such teachings were very important to many major artists of Modernism in their secular search for the spiritual. Artists of the Surrealist era were especially interested in various esoteric traditions from Alchemy to Zen. One of these artists was Duchamp. If he had not had some kind of insight into the nature of the transcendent realm, Duchamp might well have continued as a follower of the Cubists, as in his quasi-Cubist composition of 1911 The Chess Players (Fig. 6). Chess was his favorite game, and he worked out many pictorial space-time problems

click to enlarge

Figure 7

Marcel Duchamp,Bride, 1912

around this theme. But he soon saw all this “retinal art” (as he called it) as extremely limited. He wanted to return art to something that could be (as he said) “at the service of the mind.”(11)

In 1912 came Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 and then the Bride(Fig. 7), as Duchamp rapidly moved past the last vestiges of Cubism toward purely mental, imaginary images. The new images start to center on semi-mechanical metaphors. In the process of changing styles, Duchamp was seriously questioning selfhood. He told Pierre Cabanne how much he had been regretting that art no longer had its traditional functions: “religious, philosophical, moral.”(12) He looked back on the Dada movement that developed during World War I as not just fun and games (even though that was a large part of it), but also as:

…an extreme protest against the physical side of painting.

It was a metaphysical attitude. … It was a way to get out of

a state of mind…to get free.

Dada was very serviceable as a purgative. And I think I was

thoroughly conscious of this at the time and of a desire to effect

a purgation in myself. … (13)

Duchamp also recalled : “My intention was always to get away from myself…”.(14)

It is said that once Little Self is out of the way, or at least set aside a bit, windows rapidly open toward hitherto unknown realms. One of the radical questions Duchamp was asking himself early on was, “Can one make works which are not works of ‘art’?”(15)

One of his radical answers was the revolutionary “ready-made”, which he described as “a work of art for which there is no artist.”(16) His ready-mades were industrial products that he selected and signed, declaring them works of art. He went on to redefine art in a highly democratic way by stating that art is whatever an artist says is art (not what critics say is art). Many critics still hate him for that. By removing the “artist” from the center of the concept of art, Duchamp also seems to have been removing the assumed importance of his own Little Self, and thus the whole ego-centered idea of self-importance and self-expression. In short, he seems to have been moving toward Androgyny.

There are a number of traditional indications of how much a person is self-centered. One is aggressiveness. Duchamp was anything but aggressive. He was gentle and humorous, confident and resolute; he never forced himself on others. Another traditional indication is how much money and material wealth one thinks one needs. Duchamp had little desire for money. His indifference to it was legendary. Duchamp owned very little. For most of his life what he owned would fit into a couple of suitcases and a few boxes. Another sign is whether or not one needs to dominate a conversation, and make others agree with you. Duchamp went out of his way to allow people their positions, as people, as artists, or as critics, even if he did not agree.

Was he also spontaneous and humorous? Yes. Indeed, he loved word-play and was an incurable punster. Another indication of Androgyny is said to be how much attention is paid to what others think of you, and how you treat other people. Duchamp seldom bothered to read what people wrote about him. Nor, for most of his life, did he feel the need to exhibit what he made. He did not have a retrospective exhibition until 1963. He also tried to live without selling his unique work, except to a few private patrons, by working in a library, teaching French, dealing Brancusi’s art, and selling multiples.

Was he also generous and supportive of others? Yes. Was he able to feel so deeply into the heart of other artists that even short conversations with him often were transformative experiences? Yes. Many artists have testified to that. Indeed it is often said that no major artist of the last fifty years was not affected by Duchamp to some degree. Several thick books could be written on that subject.

Was he also deeply involved with experiencing and communicating transpersonal truth? Very much so. Did he frequently point toward the transcendent in his work? Yes, as we shall see. According to the Perennial teachings, this is what Androgynous people do, and they do it with spontaneous fluidity and grace. Did his thoughts and actions proceed with unusual fluidity and grace? Yes. Here, for example, is an observation by Georgia O’Keeffe:

It was probably in the early twenties when I first saw Duchamp. …

I don’t remember seeing anyone else at the party, but Duchamp was there… .

I was drinking tea. When I finished he rose from the chair, took my teacup

and put it down at the side with a grace that I had never seen in anyone before

… . I don’t remember anything else about the party.(17)

Duchamp’s dear friend Beatrice Wood expressed the feelings of many: “He had the objectivity of a guru. His mind touched stillness, beholding the unity of life.”(18) Arturo Schwarz, his dealer and cataloger, said: “I dare say he was a guru, in the Indian sense of the word. He would not, of course, have favored being so called. … His simplicity was a way of being, modesty was never a pose with him, he was as natural as his breath. He was generous and understanding. … his advice could not have been wiser and his concern would never be merely skin deep.”(19)

The traditional teaching is that so long as one’s awareness is contained within the psychological sphere of the ego, one cannot see beyond the realm of space and time. However, Duchamp obviously was moving beyond that. He was very much involved with perceiving and evoking the realm he described as “beyond time and space.” If we assume that one has connected some of one’s personal, qualifying consciousness with the unqualified consciousness, how can one express the transcendent experience of those higher realities? Words work well to identify realities that exist inside the measurable world, the sphere of space and time. Beyond that sphere, any attempt to use words in the usual descriptive way is useless. How can one pictorialize the invisible? How to verbalize or visualize the transcendent are parallel problems. The most one can do is to suggest the transcendent with symbols and metaphors.

Much of Duchamp’s work appears to have been the result of his efforts to do just that. Yet he is dismissed by some as merely humorous if not nihilistic. If there is something more, how might we find the wisdom that he wrapped in so many smiles? My approach has been to listen closely to his words, examine the philosophical context in which he did much of his thinking, and then focus on a singular metaphor that he used regularly, the Androgyne. Such an analytical approach (alas) will be somewhat more linear and “heavier” than Duchamp’s light touch. Keep in mind that much of what he said was said with a smile, and that seems to be true of his visual work as well.

The Androgyne Before & After Duchamp

|

“The true mythical androgyne is equally male and female at the same time.” “…spiritual perfection consists precisely in rediscovering with oneself this androgynous nature.” |

As already noted, certain sacred symbols have been in use continuously for centuries. Among the best-known are double images of nonduality, e.g., those by which world religions symbolize themselves: the Yin-Yang of Taoism, the Circle-Square (or Mandala) of Buddhism, the Double Triangle of Judaism, and the Cross of Christianity. As has been discussed, each symbol is both a two-ness and a oneness. All these double images are intended to remind us of the higher unity that transcends all forms of multiplicity. What seems to be two is one ultimately. Spirit and matter are one. Sky and Earth are one. Male and female are one.

All those double images of nonduality are rendered in a visual language that is geometric. Geometry as a sacred visual language did not become common until after the Old Stone Age. In other words, abstract geometric forms of this type are part of the settled, post-nomadic experience. There are other double-images images of nonduality which are much older, going back to the Old Stone Age. This group is pictorial, naturalistic, not geometric. The best known examples include the Double-Serpent, which began in the Paleolithic era and has continued into our time as the medical caduceus, and the Flying Serpent whose various forms include the Quetzalcoatl of the Aztecs, and the cosmic Dragons of Asia. The heavenly and the earthly are united in this symbol of what might be called bi-singularity.

The least known of these primordial pictorial symbols is the Androgyne – a single human body which is part-male and part-female. The Androgyne image also has been with us since the Paleolithic era. In Asia it is better known than in the West, where its history and meaning usually are studied only by students of sacred art, archeology, religion, and mythology. Like all works of sacred art, images of the Androgyne are teachings in and of themselves–visual expressions of metaphysical truth.

click to enlarge

Figure 8

Androgynes from Around The World:

Europe, India, China, the

Middle East, & the Americas

To introduce this mythic image – its structure, antiquity, and ubiquity – I prepared a digital collage of images from the tribal world to the modern world (Fig. 8). In this collage, we see a Stone Age work from North America, a Bronze Age image from the Near East, the Goddess Kuan Yin (with a mustache) from China, Shiva-Shakti from India, and an Alchemical Androgyne from Christian Europe. Each visual metaphor is different, but the essential teaching is the same. Nonduality refers to the highest possible level of human consciousness.

The purpose of an “illuminating image” is to illuminate. As an image that is a teaching, it can be approached in various ways. Monks can meditate deeply for years on the meaning of Androgyny as they work to become Androgynes themselves. For first-time viewers, the image can be quite shocking. It is a very irrational image. Logic cannot comprehend it. Happily, there are other ways of knowing.

A well-delivered shock can jolt the first-time viewers out of their habitual reliance on linear, left-brain logic. The experience can be like what happens when one tries to deal with a Zen koan, for example, trying to answer the question “What is the sound of one hand clapping?” When logic proves useless, one tends to shift into intuitive, right-brain modes of knowing. That is exactly what the abbot of every Zen koan monastery wants the monks to be doing.

Only when the intuition of the monks is as highly developed as their reasoning are they ready to graduate from the monastery and go out to be of service to the world. It is this internal harmony of the “male & female” within us, the “sun & moon” within us, reason and intuition within us, that makes possible the highest form of human wholeness, an Enlightened state of being. When Golden Consciousness emerges, according to the Perennial Philosophy, one is no longer self-serving, or able to love in only qualified ways. One exists for the benefit of others, and every act is an act of love.

We can also consider Androgyny from the perspective of modern brain science. At a 1978 conference of psychologists and anthropologists on bimodality I presented a paper demonstrating that there is a one-to-one relationship between how bilateral Androgyne images are rendered in sacred art and the left/right brain. His/Her left side (which actually is controlled by the right brain) always is female. His/Her right side (which actually is controlled by the left brain) always is male. Those present were as surprised as I was to see this relationship. Shortly thereafter I was invited to teach the history of sacred art at the California Institute of Asian Studies in San Francisco, where the faculty included respected practitioners of the major spiritual traditions.

I asked each of them if the newly discovered left/right brain is an appropriate metaphor for the Perennial teaching of integrating our rational and intuitive faculties in order to attain Enlightenment. Every teacher there, Christian, Jewish, Hindu, Buddhist, and Taoist, said yes–with the qualification that scientific understanding is only a partial understanding of traditional wisdom. A similar answer was given to me by a number of Tibetan Buddhists, including Lama Govinda, and the Venerable Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche. These interviews supported my growing belief that the discovery of left/right brain was not a trivial fad in popular psychology but something of special importance for the modern world–a concrete, scientific way for anyone to start to think about the psychodynamics of Androgyny and striking confirmation of what Duchamp told me a decade earlier.

click to enlarge

Figure 9

Native American

Androgyne, Stone Age type

Figure 10

African Androgyne

(Sudan), Stone Age type

To see in more detail how Androgyny has been symbolized in traditional sacred art, the following selection of images provides a general overview of the various types of Androgyne iconography that have been rendered around the world from the Stone Age to the present.(20) Representing the Stone Age is a painted image from North America. This figure has breasts and an erect phallus (Fig. 9). Among the neolithic tribes of Africa, it is typical to see images of the Androgyne with breasts and a beard (Fig. 10). That symbolism was continued by Bronze Age Egyptians. Other Bronze Age artists portrayed the Androgyne as a single body with male and female faces, often in association with the Double-Serpent and/or the Sun-Moon (Fig. 11). More widely published are Iron Age images of the Androgyne as a male-female with one breast, as Shiva-Shakti is often seen in Hindu India where there are more sculpted and painted Androgyne images than anywhere else (Fig. 12). In the esoteric tradition of Judaism, the image of Adam Kadmon is central to the Kabbalah (Fig. 13). In the esoteric tradition of Christianity, many versions of the Androgyne image fill Alchemical books and manuscripts of the Renaissance. There are more Androgyne images to be found in those books than anywhere else in the Western art of the modern era (Figs. 14 & 15; 16 & 17). In all these spiritual traditions, the Androgyne symbolizes both divinity among the Gods and Goddesses, and the possibility of psycho-cosmic wholeness here on earth.

click images to enlarge

- Figure 11

- Figure 12

- Figure 13

- Neo-Babylonian Androgyne,

Late Bronze Age/Early

Iron Age type - Hindu Androgyne (Ardhanarisvara

/ Shiva-Shakti), Iron Age type - Jewish Androgyne (Adam Kadmon), Iron Age type

click images to enlarge

- Figure 14

- Figure 15

- Christian

- Androgynes (Alchemical), 17th century

click images to enlarge

- Figure 16

- Figure 17

- Christian Androgynes (Alchemical),

17th and 18th centuries - Christian Androgynes (Alchemical),

17th & 18th centuries

Those traditional images, especially in Stone Age art and the Alchemical book illustrations of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, were the type of Androgyne images that were known to modern artists in the early twentieth century. Inspired by such images, artists of the Dada-Surrealist era rendered many contemporary variations on this ancient theme as they searched for Androgyny within themselves. A comprehensive survey would show how virtually every major artist of the Surrealist era focused on this iconography. What follows is a small selection of their Androgyne images. The dates range from 1916 to 1954. Most of the artists represented in this portfolio were friends of Duchamp.

click to enlarge

Figure 18

Paul Klee, Barbarian’s

Venus, 1921

BBarbarian’s Venus by Paul Klee (1879-1940) is one of the most “barbaric” Androgyne images of the era. She is a Venus with a penis(Fig. 18). Klee was not a member of the Surrealist circle, but sometimes exhibited with them. He was associated with Kandinsky and Marc in Munich in 1911 and 1912, then took from Cubism and Orphism the concept of fluctuating planes. Klee was thought by some to be an Alchemist when he discussed the Absolute, Nothingness, and the Ground of Being. His students at the Bauhaus (only half in jest) called him “Heavenly Father.” He was one of the first modern artists to explore Androgyny in tribal art.

click to enlarge

Figure 19

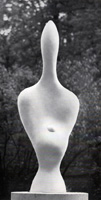

Constantin Brancusi,

Princess X, 1916

Constantin Brancusi (1876-1957) was a very close friend of Duchamp. He studied Androgyne symbolism first in Theosophy and then in the tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. A book of Tibetan teachings was on his bedside table for many years. He and Duchamp worked together, played together, and seem to have shared many ideas about the etheric, the infinite, and the Androgynous. Such concepts were central to both artists. In 1916 Brancusi sculpted Princess X (Fig. 19). Most of the critics of the time did not like it. It was too abstract. One was particularly offended by the phallic form. Similar criticism greeted Brancusi’s most famous work, “Bird in Space.” Brancusi called it “Bird of the Ether” because the upward thrust is toward the etheric realm, beyond the realm of space and time, the realm that only Androgynous consciousness can reach. In spite of the phallic interpretations of many viewers, “Bird of the Ether” clearly is about not sexuality but transcendence.

click to enlarge

Left :Figure 20

Jean Arp, Demeter, 1960

Figure 21

Jean Arp, Idol, 1950

Jean (Hans) Arp (1888-1966) often read Alchemical texts by Jacob Boehme and felt art should lead beyond self-expression to spirituality. He and his good friend Max Ernst made sure this attitude was part of the Dada movement and early Surrealism. Later he was deeply inspired by Brancusi’s fluid style. He carved a number of beautiful Androgynes. His Demeter makes use of the traditional Iron Age symbolism of the Goddess-God with one breast (Fig. 20). For his Idol (Fig. 21) Arp seems to have gone farther back in time for his iconography, back to the Androgyne symbolism of the Stone Age and Bronze Age, when it was not uncommon for idols to have an abstract female body and a tall abstract phallic neck/head (Figs. 22A &22B).

click images to enlarge

- Figure 22A

- Figure 22B

- Old Stone Age figures

thought to be Androgynes - New Stone Age/Bronze

Age figures thought to

be Androgynes

click to enlarge

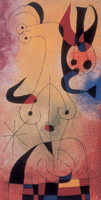

Figure 23

Joan Miró, Dawn Perfumed

by a Shower of Gold, 1954

Joan Miró (1893-1983) spoke of wanting his art to express the unity of the finite and the infinite. He was particularly interested in Stone Age art in his later years and used the ancient phallic neck/head symbolism of the Stone Age in his Androgynous painting “Dawn Perfumed by a Shower of Gold.” The lower part is quite female, while the upper part is quite male (Fig. 23).

Nudes, Rroses, etc.

|

“Is it a woman? No. Is it a man? No. …I have never thought which it is. Why should I think about it?” |

As we have seen, Duchamp was not the only artist of the Dada-Surrealist era interested in Androgyny. The image of the Androgyne was very important to many of the major artists in this circle. They talked about Androgynes in Alchemy, as well as in esoteric Hinduism and esoteric Buddhism wherein the Androgyne also is a primal symbol for Enlightened consciousness. They knew what the Androgyne is, and considered it the ideal condition of human awareness. This is not to say that all these artists actually attained Androgyny, but only to indicate that Androgyny was, to a large extent, their common goal. Even though many Surrealist artists rendered images of the Androgynes and were working towards the condition of Androgyny within themselves, Duchamp devoted more years of his life to articulating images of the Androgyne than any other major artist of the twentieth century, with the possible exception of his good friend Max Ernst. More has been written about Duchamp’s Androgyne images than about anyone else’s modern Androgyne images, but the focus of most of the literature has been on gender issues not metaphysics. This book is about metaphysics.

Some would begin the list of Duchamp’s Androgyne images with Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 of 1912, his most famous painting. While most people simply assume the nude is female, a close examination reveals there is a gender question. Is the figure male or female? “Nu” in French can mean male or female, and the visual evidence is not conclusive. This very ambiguity is interpreted by some as being Androgynous, especially in light of the unusual way Duchamp responded to the gender question in a 1916 interview: “Is it a woman? No. Is it a man? No. To tell you the truth, I have never thought which it is. Why should I think about it?”(21) Some think the slightly later Bride also is an Androgyne image, but that depends largely on how one interprets The Large Glass.

Others would begin the list with L.H.O.O.Q. of 1919 where Duchamp added a mustache and beard to Leonardo’s “Mona Lisa,” having heard that Leonardo was homosexual. This modified ready-made clearly was intended as a joke, but it also clearly was a deliberate form of Androgyne imagery.

click to enlarge

Figure 24

Marcel Duchamp, Fountain

, 1917 (1964 replica)

Figure 25

Marcel Duchamp, Bottle Dryer

, 1914 (1963 replica)

Some would begin the Androgyne list two years earlier with Fountain – the signed ready-made urinal of 1917(Fig. 24). To declare this plumbing fixture a work of art certainly was a striking challenge to the aesthetic sensibilities of the time, and for many still is a challenge. Even though it is now accepted as a work of art, what might be Androgynous about it? Several people interested in religion (as Duchamp himself was not) looked at this image in 1917 as an abstract form of Buddha or the Virgin Mary. Male Buddha/Holy Mother? Perhaps the combination of those two holy images would be an Androgyne? It would echo the ancient idea of Androgyny if the combination of Divine Mother/Divine Son were deliberate, but there’s no evidence that this was the case in Duchamp’s mind. Some (with a Freudian psychology) see this open receptacle as a female space into which a male enters. This may have been slyly sexual symbolism on Duchamp’s part, but the symbolism of common copulation is not the iconography of Androgyny. The same goes for the ready-made Bottle Dryer of 1914 (Fig. 25). Some see the elements that hold the drying bottles as male and the implied bottles as female. That symbolism may be humorously sexual, but it is not inherently Androgynous.

Not so with the gender-bending character Duchamp created as a female alter ego in 1920:Rrose Sélavy. After his Mona Lisa of 1919, we find a string of Androgyne images in Duchamp’s work, some humorous, some serious. He worked on these Androgyne images every decade for the rest of his life. Rrose even “signed” a number of major objects, as well as most of his literary works over the next twenty years. Was Duchamp homosexual? No. Was he bisexual? No. Neither was he homophobic. He had any number of homosexual and bisexual friends. Did he dress in drag regularly? No – only when making a work of art (Figs. 26, 27, 28). This series of male-female images from 1919 to 1942 certainly was intended to be amusing, but they also publicly propagated the idea of Androgyny as “food for thought.” He did not stop thinking about the Androgyne. In 1946 Duchamp secretly began work on the monumental Androgyne image that would occupy him for most of the rest of his life.

click images to enlarge

- Figure 26

- Figure 27

- Figure 28

- Marcel Duchamp, “Belle Haleine (Beautiful Breath)” Perfume Bottle, with a photograph of Rrose Sélavy (alias Marcel Duchamp) by Man Ray pasted on, 1921

- Marcel Duchamp, RROSE SÉLAVY in the “Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme,” Paris, 1938 (female mannequin half dressed in Duchamp’s

clothing) - Marcel Duchamp, Compensation-Portrait in the exhibition “First Papers of Surrealism,” New York, 1942

An early examination of the Androgyne in Duchamp’s work was written by Arturo Schwarz in the 1960s. Some of the theoretical assumptions of Schwarz are quite strange, and have been rejected by a large number of Duchamp specialists. His articulation of the meaning of Androgyny is often imaginative and not always consistent. However, Schwarz deserves credit for his early attempt to bring Androgyny into the art-historical dialogue around Duchamp. He did so from the perspective of Alchemy, the basic principles of which he has articulated clearly. Here is a passage from his essay “The Alchemist Stripped Bare in the Bachelor, Even”:

“…for the adept to achieve higher consciousness means, in the first place, acquiring ‘golden understanding’ (aurea apprehensio) of his own microcosm and of the macrocosm in which it fits. It is in the course of his pursuit of the Philosopher’s Stone that he acquires this new awareness. Thus the quest is more important than its reward; as a matter of fact, the quest is the reward. Alchemy is nothing other than an instrument of knowledge – of the total knowledge that aims to open the way toward total liberation. … Individuation, in the alchemical sense, entails abolishing the conflicting male-female duality within the integrated personality… . Eliade has pointed out that ‘to be no longer conditioned by a pair of opposites results is absolute freedom’.”(22)

Some, including Schwarz, Jack Burnham, Ulf Linde, John F. Moffitt, and others, have worked hard to have us see Duchamp as an Alchemist. Duchamp, however, offered little support for this belief. Indeed, he made efforts to deny it. When I met Duchamp in 1967 I had been studying the symbolism of Alchemy for a number of years and suspected that he might be an actual Alchemist.

While it is true that the Androgyne is the goal of Alchemy, it is possible to have a particular interest in the Androgyne without being an Alchemist. I did not understand this at the time. Duchamp illuminated me. Here is how one of our conversations went:

|

LG:

|

It seems that almost from the beginning of your work as an artist, you have had a philosophical attitude toward what being an artist is. In one of your interviews with Sweeney, for example…, you describe Dada as a “metaphysical attitude.” What you have talked about and written is permeated with the thought-feelings of a philosopher. At the end of your 1956 interview with Sweeney, you spoke of art as a path “toward regions which are not ruled by time and space.” |

|

MD:

|

Was that the one filmed in Philadelphia? |

|

LG:

|

It was. |

|

MD:

|

Yes. Perhaps that is about as much as you can say in a film being made for wide consumption. If one says too much more, the result is simply a great deal of misunderstanding. Understanding can only emerge from a co-experience, a non-verbal experience which the artist and the onlooker can share by means of aesthetic experience. So I leave the interpretation of my work to others. |

|

LG:

|

Nevertheless, I think it would be correct to say that you regard the practice of art as a philosophical path toward that which is beyond time and space. |

|

MD:

|

That is correct. That is my view, but only part of my view. My view is beyond and back. Some get lost “out there.” My frame of reference is out of the frame and back again. |

|

LG:

|

That sounds like the dance of the finite and infinite, stepping back and forth between three dimensions and four dimensions, as Apollinaire or Mallarmé would say. |

|

MD:

|

So it does. No one says it better than Mallarmé! |

|

LG:

|

May we call your perspective Alchemical? |

|

MD:

|

We may. It is an Alchemical understanding. But don’t stop there! If we do, some will think I’ll be trying to turn lead into gold back in the kitchen (laughing). Alchemy is a kind of philosophy, a kind of thinking that leads to a way of understanding. We may also call this perspective Tantric (as Brancusi would say), or (as you like to say) Perennial. The Androgyne is not limited to any one religion or philosophy. The symbol is universal. The Androgyne is above philosophy. If one has become the Androgyne one no longer has a need for philosophy. (23) |

Notes

1. Duchamp in conversation with Lanier Graham, 1968. Quoted in Graham, Marcel Duchamp: Conversations with The Grand Master (New York: Handmade Press, 1968) 3. For more of this conversation, see below, 5.

1. Duchamp in conversation with Lanier Graham, 1968. Quoted in Graham, Marcel Duchamp: Conversations with The Grand Master (New York: Handmade Press, 1968) 3. For more of this conversation, see below, 5.

2. Duchamp in conversation with William Seitz, 1963. Quoted in “What’s Happened to Art?: An Interview with Marcel Duchamp” in Vogue (15 Feb. 1963) 113.

2. Duchamp in conversation with William Seitz, 1963. Quoted in “What’s Happened to Art?: An Interview with Marcel Duchamp” in Vogue (15 Feb. 1963) 113.

3. Duchamp in conversation with J. J. Sweeney, 1956. Quoted in Michel Sanouillet & Elmer Peterson, eds.,Salt Seller: The Writings of Marcel Duchamp (New York: Oxford University Press, 1973) 137. [hereafter “SS.”]

3. Duchamp in conversation with J. J. Sweeney, 1956. Quoted in Michel Sanouillet & Elmer Peterson, eds.,Salt Seller: The Writings of Marcel Duchamp (New York: Oxford University Press, 1973) 137. [hereafter “SS.”]

4. Duchamp, “The Creative Act” – a talk in Houston at a meeting of the American Federation of Art, 1957. Quoted in Sanouillet 138.

4. Duchamp, “The Creative Act” – a talk in Houston at a meeting of the American Federation of Art, 1957. Quoted in Sanouillet 138.

5. The best-known book on this subject is Aldous Huxley, The Perennial Philosophy (London: Chatto & Windus, 1946 & later editions). For a bibliography, see Lanier Graham, “The Perennial Philosophy: A General Bibliography” in Iconography of Infinity: Essays on Art & Philosophy, vol. 2, no. 1 (Spring 1993). The best-known twentieth century writers on this subject include Titus Burckhardt, A. C. Coomaraswamy, Réné Guenon, Karl Jaspers, Frithjof Schuon, Huston Smith, Alan Watts, and Ken Wilber.

5. The best-known book on this subject is Aldous Huxley, The Perennial Philosophy (London: Chatto & Windus, 1946 & later editions). For a bibliography, see Lanier Graham, “The Perennial Philosophy: A General Bibliography” in Iconography of Infinity: Essays on Art & Philosophy, vol. 2, no. 1 (Spring 1993). The best-known twentieth century writers on this subject include Titus Burckhardt, A. C. Coomaraswamy, Réné Guenon, Karl Jaspers, Frithjof Schuon, Huston Smith, Alan Watts, and Ken Wilber.

8. The Gospel of Thomas 22 in Doresse, Les Livres Secrets des Gnostiques d’Egypt, vol. 2 (Paris, 1959) 157.

8. The Gospel of Thomas 22 in Doresse, Les Livres Secrets des Gnostiques d’Egypt, vol. 2 (Paris, 1959) 157.

10. Ruminations on Zen Cows, Part 4 (1998) 3 <www.HsuYun.org/Dharma/ZBOHY/zencows>.

10. Ruminations on Zen Cows, Part 4 (1998) 3 <www.HsuYun.org/Dharma/ZBOHY/zencows>.

12. Duchamp in conversation with Pierre Cabanne. Quoted in Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp(New York: Da Capo Press, 1967) 43.

12. Duchamp in conversation with Pierre Cabanne. Quoted in Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp(New York: Da Capo Press, 1967) 43.

14. Duchamp in conversation with Katharine Kuh. Quoted in Kuh, Artist’s Voice: Talks with Seventeen Artists (New York: Harper & Row, 1962) 82. Duchamp went on to add: “though I knew perfectly well that I was using myself. … Call it a little game between ‘I’ and ‘me’.” It would be interesting to collect all of Duchamp’s statements about ego, self, etc. Included would be the following from the Western Round Table on Modern Art, San Francisco, 1949: “…the ‘victim’ of an esthetic echo is in a position comparable to that of a man in love, or a believer, who dismisses automatically his demanding ego and…submits… “. Quoted in Clearwater, ed., West Coast Duchamp (Miami Beach, FL: Grassfield Press, 1991) 107 and 110; Also this statement: “And artists are such supreme egos! It’s disgusting.” Quoted in Tomkins, The Bride & The Bachelors (New York: The Viking Press, 1965) 67.

14. Duchamp in conversation with Katharine Kuh. Quoted in Kuh, Artist’s Voice: Talks with Seventeen Artists (New York: Harper & Row, 1962) 82. Duchamp went on to add: “though I knew perfectly well that I was using myself. … Call it a little game between ‘I’ and ‘me’.” It would be interesting to collect all of Duchamp’s statements about ego, self, etc. Included would be the following from the Western Round Table on Modern Art, San Francisco, 1949: “…the ‘victim’ of an esthetic echo is in a position comparable to that of a man in love, or a believer, who dismisses automatically his demanding ego and…submits… “. Quoted in Clearwater, ed., West Coast Duchamp (Miami Beach, FL: Grassfield Press, 1991) 107 and 110; Also this statement: “And artists are such supreme egos! It’s disgusting.” Quoted in Tomkins, The Bride & The Bachelors (New York: The Viking Press, 1965) 67.

16. Duchamp in conversation with Francis Roberts. Quoted in “I Propose to Strain the Laws of Physics” inArtnews (Dec. 1968): 47. Duchamp questioned himself this way in a 1913 WB note; IBID., and soon developed the ready-made.

16. Duchamp in conversation with Francis Roberts. Quoted in “I Propose to Strain the Laws of Physics” inArtnews (Dec. 1968): 47. Duchamp questioned himself this way in a 1913 WB note; IBID., and soon developed the ready-made.

17. O’Keeffe, quoted in d’Harnoncourt and McShine, eds., Marcel Duchamp (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1973) 212.

17. O’Keeffe, quoted in d’Harnoncourt and McShine, eds., Marcel Duchamp (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1973) 212.

18. Beatrice Wood, “Marcel,” in Kuenzli and Naumann, eds., Marcel Duchamp: Artist of the Century(Cambridge: MIT Press, 1987; 1990) 16. For the story of their half-century relationship, see I Shock Myself: The Autobiography of Beatrice Wood (San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books, 1988).

18. Beatrice Wood, “Marcel,” in Kuenzli and Naumann, eds., Marcel Duchamp: Artist of the Century(Cambridge: MIT Press, 1987; 1990) 16. For the story of their half-century relationship, see I Shock Myself: The Autobiography of Beatrice Wood (San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books, 1988).

20. Most of the literature on Androgynes in art is limited to the historical era, when there are written documents. The prehistoric images have been more difficult to interpret owing to a lack of written documents. For a century, scholars have had little to say about the many Stone Age figures that clearly have female bodies but also have strange tall neck/heads. Many figures of this type have been classified as having the shape of a violin. No male/female symbolism was detected. In more recent scholarship we find the fact that there seems to be an unbroken continuity of such symbolism from the Old Stone Age through the New Stone Age, and the reasonable theory that such figures with “phallic necks” are to be interpreted as being male& female simultaneously. For illustrations of such female figures with “phallic necks,”see Gimbutas, The Goddesses and Gods of Old Europe 6500-3500 BC (Berkeley , LA: University of California Press, 1974 & 1982; 1990) 133, 135, 154, 157, 202; and Gimbutas,The Language of the Goddess (San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco, 1995) 82, 183, 230, 231, 232. The oldest figures of this female/male type in Old Europe (#356 & #357) date from between about 20,000 and 15,000 BCE. For parallel images from other parts of the world, see Lanier Graham, “The Great Goddess-God, The Divine Androgyne,” in Goddesses in Art (New York: Artabras, 1997) 43-47.

20. Most of the literature on Androgynes in art is limited to the historical era, when there are written documents. The prehistoric images have been more difficult to interpret owing to a lack of written documents. For a century, scholars have had little to say about the many Stone Age figures that clearly have female bodies but also have strange tall neck/heads. Many figures of this type have been classified as having the shape of a violin. No male/female symbolism was detected. In more recent scholarship we find the fact that there seems to be an unbroken continuity of such symbolism from the Old Stone Age through the New Stone Age, and the reasonable theory that such figures with “phallic necks” are to be interpreted as being male& female simultaneously. For illustrations of such female figures with “phallic necks,”see Gimbutas, The Goddesses and Gods of Old Europe 6500-3500 BC (Berkeley , LA: University of California Press, 1974 & 1982; 1990) 133, 135, 154, 157, 202; and Gimbutas,The Language of the Goddess (San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco, 1995) 82, 183, 230, 231, 232. The oldest figures of this female/male type in Old Europe (#356 & #357) date from between about 20,000 and 15,000 BCE. For parallel images from other parts of the world, see Lanier Graham, “The Great Goddess-God, The Divine Androgyne,” in Goddesses in Art (New York: Artabras, 1997) 43-47.

21. Duchamp, quoted in Nixola Greeley-Smith, “Cubist Depicts Love in Brass and Glass” in The Evening World, New York (Apr. 4, 1916) 3.

21. Duchamp, quoted in Nixola Greeley-Smith, “Cubist Depicts Love in Brass and Glass” in The Evening World, New York (Apr. 4, 1916) 3.

22. Schwarz, in d’Harnoncourt & McShine, eds., OP. CIT. 82-83. Mircea Eliade is the twentieth century’s most widely respected historian of religions. His name continues to appear in the Duchamp literature, e.g., Francis M. Naumann, “Marcel Duchamp: A Reconciliation of Opposites” in Kuenzli & Naumann, eds., Marcel Duchamp: Artist of the Century (Cambridge and London: MIT Press, 1989) 40, note 30. Nothing was more important to Eliade than the symbolism of the coincidentia oppositorum. More Eliade citations are to be expected as Duchamp’s metaphysics are explored in more depth. During his visit to Kenyon College in 1960, I asked Eliade this question: “In our seminar on the sacred art, I want to be able to point to twentieth century artists who are still connected to the sacred. Can you suggest any?” He replied: “That is a subject I would like to write about. There are not too many in a society that has lost touch with the sacred. But I would say Chagall is reaching for Paradise, and Brancusi knows what it means to climb the axis mundi. Brancusi connected modern art with the Primal, and thereby injected a new vitality. Yes, I believe in Brancusi, and I’m told Brancusi believed in Duchamp. Is his ‘Mona Lisa with a Mustache’ only a joke or is it also an Androgyne? Several modern artists and writers have explored Androgyny. They are connecting with the Primal. They are worth examining. It also would be worthwhile to explore the abstract painters of today who are reaching beyond the skin of matter for what is underneath.” See Eliade, Symbolism, The Sacred, & The Arts (New York: Crossroad/Herder & Herder, 1986). A comprehensive study of the Androgyne in Surrealism has not been written. It will include images by many Surrealist artists and writers and such articles as Albert Béguin, “L’Androgyne” in Minotaure, 1938.

22. Schwarz, in d’Harnoncourt & McShine, eds., OP. CIT. 82-83. Mircea Eliade is the twentieth century’s most widely respected historian of religions. His name continues to appear in the Duchamp literature, e.g., Francis M. Naumann, “Marcel Duchamp: A Reconciliation of Opposites” in Kuenzli & Naumann, eds., Marcel Duchamp: Artist of the Century (Cambridge and London: MIT Press, 1989) 40, note 30. Nothing was more important to Eliade than the symbolism of the coincidentia oppositorum. More Eliade citations are to be expected as Duchamp’s metaphysics are explored in more depth. During his visit to Kenyon College in 1960, I asked Eliade this question: “In our seminar on the sacred art, I want to be able to point to twentieth century artists who are still connected to the sacred. Can you suggest any?” He replied: “That is a subject I would like to write about. There are not too many in a society that has lost touch with the sacred. But I would say Chagall is reaching for Paradise, and Brancusi knows what it means to climb the axis mundi. Brancusi connected modern art with the Primal, and thereby injected a new vitality. Yes, I believe in Brancusi, and I’m told Brancusi believed in Duchamp. Is his ‘Mona Lisa with a Mustache’ only a joke or is it also an Androgyne? Several modern artists and writers have explored Androgyny. They are connecting with the Primal. They are worth examining. It also would be worthwhile to explore the abstract painters of today who are reaching beyond the skin of matter for what is underneath.” See Eliade, Symbolism, The Sacred, & The Arts (New York: Crossroad/Herder & Herder, 1986). A comprehensive study of the Androgyne in Surrealism has not been written. It will include images by many Surrealist artists and writers and such articles as Albert Béguin, “L’Androgyne” in Minotaure, 1938.

23. Duchamp in conversation with Lanier Graham. Quoted in Graham, Marcel Duchamp: Conversations with the Grand Master (New York: Handmade Press, 1968) 2-3.

23. Duchamp in conversation with Lanier Graham. Quoted in Graham, Marcel Duchamp: Conversations with the Grand Master (New York: Handmade Press, 1968) 2-3.

Figs. 2-7, 24-28

©2002 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris. All rights reserved.