|

Dear Stephen J. Gould,

For quite a few months I had been trying to write to you about my thoughts after reading your and Rhonda Roland Shearer’s essay “Boats & Deckchairs”. I have greatly enjoyed your column since the early 90’s but this essay was especially meaningful for two reasons. First because on this occasion I thought of something you apparently did not. I was initially reluctant to accept that I might have realized something you (or Duchamp!) had not, but the more I thought about it the less reluctant I became. Now I dare to share it with you and ask for your opinion. The second reason is because on announcing your retirement from the column, I realized with a mix of joy and sadness that I would barely catch the immense pleasure and honor of sharing an issue of the magazine [Natural History] with you. As my article, “Touchy Harvestmen,” will be featured next October. I will begin with my reflections on your 4-D essay, and this will bring me back to my harvestmen’s [daddy-long-legs] 4-D perspective.

I haven’t read Abbott’s Flatland (I certainly will) but from your digested excerpts I can conclude that A Square didn’t have to fly too high above Flatland to see the shocking and never before imagined perspective being offered from a 3-D world. Of course the higher the better, but just standing a bit above the plane and stretching the neck and peeping would be enough to see Mr. Circle all at once, though somewhat deformed as an ellipse. (Similarly to when we are lost in the woods and need to climb a tree or a hill to have a map view of where the heck we are and where we are trying to go.) The perfect view of Mr. Circle is at a right angle from above, but any angle larger than zero allows for seeing him all at once, even though the shape distortion increases as the angle diminishes. I would put my money down and say that A Squares’ big “WOW!” was just after taking-off and long before reaching a straight angle above Mr. Circle. An experience much like the very first time we fly as children and realize that we can see a whole block or field all at once just after taking-off, long before reaching a complete view.

If I got that right and I properly understood that the analogy should work when going from 3-D to 4-D as well, then I think we (especially us primates) do have a chance to have that 4-D perspective of a 3-D land. In fact, the great majority of us have it all the time, literally in front of our noses. The genesis of my argument goes back to my childhood when staying late in bed. Laying on my side, I would amuse myself by switching between the two different perspectives of the landscape of blankets in front of my face, shifting as I closed each eye. Then, I would force both eyes to focus and converge on something just a few inches from my nose, and close one, and then the other (you see where I’m going?). Then I remembered a zoology teacher of mine in college saying what a “convenient idea” it was in primate evolution to have two frontal eyes, enabling us to judge distances when jumping from branch to branch. And the last relevant revelation along this line, before your essay, came when I took the instructions leaflet of my binoculars and read it (one wanders who on earth would read the directions for a pair of binoculars!). This only occurred as I was trying to kill time while waiting in the rain forest for the end of a butterfly copula that had lasted several hours already. It said that when you see through your binoculars (if they are the kind that includes mirrors), the objects not only look closer, but the 3-D view is “deeper.” This was because the two sources of the image coming from the objects to each tube are wider apart than your eyes; I thought that was pretty cool too and kept on peeping at “deeper” butterfly sex.

So when I read your article, I first thought it would be possible to do something like using two periscopes (the kind people use to see parades above the crowd) oriented sideways (and maybe slightly forward) to look at an object in front with one eye on each periscope. I wondered if the brain could still handle and integrate that (as it can when the two sources of image are slightly separated when looking at binoculars), and this would look even “deeper”, more in 4-D! However, that would be like A Square trying to see Mr. Circle from almost directly above, closer to a straight angle, with less shape distortion. But we are always looking at things from two different points anyway: from each eye. This difference is negligible with a distant object, but less and less when the object gets closer to the point where we could see it from opposite ends: between our eyes. We know since we were kids we can only focus so close, even crossing our eyes, but I think that is enough to stretch our necks out of 3-D land. A practical object to do this with is for instance is a 3.5″ floppy disk (which in fact is a solid “square” case with a real floppy disk inside, but that doesn’t matter now). It is an object with true volume, although conveniently flattened for our purposes to a couple of mm, a flattened “cube”. If you place it vertical and perpendicular to your face, just between your eyes at the minimum distance at which you can focus and converge your eyes on a single image of the edge facing you (10-20 cm), you are looking at the two full sides of the disk at once. If you close one eye, you only see the opposite side and nothing of the other.

In other words, my argument is that if we only had one eye, or if we had them on opposite sides of our head as many birds and mammals, we would be true prisoners of the 3-D prison. In that case, we would be unable to see objects from two points at the same time. As long as we have two (eyes) views of the same object (depth vision), and if I understood your essay correctly, we are having a 4-D view of the world, or at least somewhere between 3-D and 4-D. This is as if A Square stood on a chair, on its toes, stretched its neck and could see a deformed Mr. Circle. Leaving primates and owls aside, I was trying to think of animals that had shape-perception with eyes that could really look at an object from different sides at straight angles, maybe some mollusk? But even if there is such we would still need to ask it what that’s like. We would be back to where A Square was trying to explain to their friends what it’s like up there, so let’s better try it ourselves (September 16 is independence day in Mexico and they sell those periscopes in the street to see the parade, I’m getting myself two of them!).

However, visual animals are probably not the most interesting to consider for the cum-hyperhypho-embraced perspective, but those whose main perception of the world come through tactile stimuli, and which can wrap objects to perceive them. It is true that us primates, especially as kids, handle a lot of objects and get the “4-D perception” of them through our hands or mouth. This reminds me of a TV program showing how they allowed this blind-since-birth sculptor to climb on a specially made structure around Michelangelo’s David to touch and embrace (“observe”) it… he was delighted.

But the true masters of cum-hyperhypho-embracing must be something like flatworms, snakes, octopuses (in spite their good view), and one of my favorite creatures: harvestmen, or daddy longlegs. Many species, including the one I have studied, see nothing but changes in light intensity above them, and their hearing and smelling are hopeless. But they sure have legs, and they do much more than walking with them. As they progress, they are constantly assessing their very complex 3-D environment through their 8 “channels”, with an accuracy that must exceed our poor tactile perception, and that depends clearly on touching objects on several sides at the time. In short, they might not have the resolution primates or owls have, but their depth perception is clearly better, and it’s the only one they got!

During the the many field hours I was working with harvestmen for my dissertation, on top of the great fun they provided me, I frequently read your column lying in my field hammock. It was then that I shared that View of Life, never imaging that I would someday have an excuse to share details of mine with you, which is to a great extent yours anyway. Regardless of your thoughts on my 4-D speculations, I deeply thank you for all this time.

Truly yours,

Rogelio Macías-Ordóñez

Departamento de Ecología y Comportamiento Animal

Instituto de Ecología, A.C.

México

Stephen Jay Gould’s text is very interesting and full of pleasant “interactive consonants.” Though it seems important to add Frantz Fanon’s “R- assimilationist” so to speak, to the discussion. Fanon actually devoted part of his book “Black Skin, White Mask” (1952) to the importance of language and pronunciation. A doctor and trained psychoanalyst, Fanon discovered an obsession of pronouncing the letter “R” by the people from the French speaking Antilles (Martinique and Guadeloupe). To differentiate themselves from other black people in Paris during the 1950’s and 60’s, these so-called “assimiléé,” went out of their way to pronounce the rolled “R,” producing an exaggerated sound effect. The general French black population had a tendency to skip and not pronounce the consonant.

Fanon cites an example where a costumer in a Parisian coffee-shop asked loudly for a beer, consciously rolling each “R” at the appropriate moment. The result was much more than he had hoped for, and sounded like, “GARRRRÇON ! UN VÈ DE BIÈ.” The proper phrase should have been, “GARÇON ! UN VERRE DE BIÈRE.” By putting too much pressure on the first “R” in Garçon (Waiter), the man was unable to keep the two other ones, in Verre (Glass) and Bière (Beer).

This example can be reinterpreted through S.J. Gould’s approach. Here one might say that “Verre = Vert” (the color Green) and Bière = Bierre (in this case coffin, like the shape of the Rigaud perfume bottle). Finally, “Eau de Voilette,” the piece of cloth used by widows to cover their face can be read also as “Eau de Violette” (color for the funeral).

As an additional grammatical point, the gender for the word CORDE is feminine, not masculine. In French we say “une corde,” and in accordance with S’ ACCORDE (liaison) it becomes SA CORDE (Her Rope).

I loved the whole text. Best regards,

Marc Latamie

Illustration 4

Photograph showing a

lady veiled in the antique lacespan>

Photograph of Marcel

Duchamp by Hans

Hoffmann, Munich, 1912

“L’oeuvre d’art est toujours basée sur ces deux poteaux du générateur et du spectateur, et

l’étincelle qui vient de cette action bipolaire donne naissance à quelque chose comme l’électricité.”

Bill Tanch

Dear Dr. Gould;

When I saw the headline of the article you and your wife wrote in the December-JanuaryNatural History, as a chemist, one thought came to my mind: cyclohexane. As I read the article, I realized that the connection may be germane.

When learning organic chemistry, the structures initially are written as two-dimensional. Only later are three-dimensional representations introduced. Hence, methane (CH4) initially is presented as a Greek cross with carbon in the middle and the four hydrogens attached to it as the directions of the compass, with angles of 90º. Later, one learns the actual three-dimensional structure is different. Mutual repulsion keeps the hydrogens as far away from each other as possible, giving a tetrahedral structure.

Similarly, initially, cyclohexane is written on the board or paper as a perfect hexane. When the third dimension is introduced, we learn that the structure is puckered, with two more-or-less stable confirmations, called the boat and the chair.

The chair structure is somewhat more stable in cyclohexane and therefore is the predominant one existing in nature in the pure compound. But the substitution of other groups for some of the hydrogens may make a difference in which structure is preferred.

I find it interesting that Duchamp picked these two objects, boat and chair, to represent his thoughts on three- and four-dimensional world, while we chemists associate them with the difference between two- and three-dimensional representations. Is it a coincidence?

Sincerely yours,

Robert Ausubel

New York, NY

click to enlarge

Illustration 1

Duchamp’s Studio,

33 West 67 Street,

New York, 1917-18

© 2000 Succession Marcel

Duchamp ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

click to enlarge

Illustration 2

Marcel Duchamp,

Unhappy Readymade, 1919

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

The Duchamp Bicycle Wheel(1913), and Stool was only referred to by Duchamp but was never seen because Duchamp claimed that it was “lost” and undocumented by any photographs.

The 1941 print of his Bicycle Wheel in the Boite en Valise (the first time that we see a visual representation relevant to, but not actually depicting, his 1913 original) was chosen by Duchamp from a series of at least five studio photographs (circa 1916-17) taken of the2nd version, made in his New York studio. The photograph that Duchamp selected to use for creating his 1941 Boite pochoir print appears to be retouched. (We are in the process of subjecting this image to forensic analysis for further determination of the specific alterations.) Based upon the depicted bicycle wheel and stool shapes, I argue that the movement of the wheel would hardly be relaxing (as in watching a fireplace) but would, in fact, continually wobble out a warning of an eventual crash and fall of the stool. (See my article “Why is the Bicycle Wheel Shaking?”)

click to enlarge

Illustration 3

Marcel Duchamp,

Rrose Sélavy by Man

Ray, 1921

© 2000 Succession Marcel

Duchamp ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

Illustration 4

Marcel Duchamp,Cover for

“Le Surréalisme, même,” Winter

1956, 1956

© 2000 Succession Marcel

Duchamp ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

In addition to the distorted shape of the bicycle wheel and stool in the source photograph for Duchamp’s 1941 Boite en Valise print (see Illustration 1), the stool rungs and legs are extremely blurred in ways that contrast with the other, more sharply-focused, surface. One is led to ask — are the legs and rungs askew due to photographic or physical alterations? Duchamp’s use of photographic alterations would not be surprising. Scholars readily acknowledge that Duchamp, throughout his career, retouched photographs. Examples include Unhappy Readymade (1919) (where Duchamp adds the appearance of a printed geometric axiom to a photograph of book pages whose typeface had been washed away by rain), the famed Rrose Selavy portraits (1921) by Man Ray (where Duchamp enhances Rrose’s hands), and the cover of Surrealism, Même (1956) (where Duchamp retouches a photograph of his concave fig leaf sculpture to enhance the illusion of convexity already, in part, created by special effects lighting). (See illustrations 2, 3, 4)

click to enlarge

Illustration 5

Marcel Duchamp,

Photo of Duchamp riding

on the Bicycle, 1902

© 2000 Succession Marcel

Duchamp ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

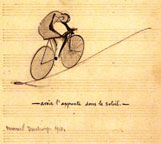

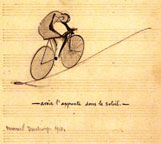

Illustration 6

Marcel Duchamp,

To Have the Apprentice

in the Sun, from the

Box of 1914, 1914

© 2000 Succession Marcel

Duchamp ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

Moreover, Duchamp knew that the common bicycle design for front wheels incorporated a curved fork and yet in his 1916-17 2nd version he uses a straight fork! Note here a boyhood photo of Duchamp riding his bicycle in 1902 and his drawing from the 1914 Box — both depicting the curved forks that were conventionally used even when Duchamp was a child (see Illustrations 5 & 6). One must not forget that enthusiasm for new technologies, gadgets and inventions was at its zenith in the early 20th century. Since straight forks were only briefly in used in modern “safety bicycle” design (and therefore quickly became obsolete by the late 1880’s), Duchamp appears to be making a conscious point when he selects, in 1916-17, an obsolete design for a “readymade” during an era that embraced hi-tech mass production. Even in 1916-17, most junked bicycle fork parts readily found (using modern spoked wheel and metal rim) would be curved in shape and any straight fork design infrequently found as visual oddity appearing retrograde and old-fashioned (and most often seen with a primitive wheel and wood spokes).

click to enlarge

Marcel Duchamp,Fountain,

1917 © 2000 Succession Marcel

Duchamp ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris

Marcel Duchamp,Trébuche

t (Trap), 1917 © 2000 Succession

Marcel Duchamp ARS,

N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

Marcel Duchamp,

Hat Rack, 1917

© 2000 Succession

Marcel Duchamp ARS,

N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

We truly appreciate the effort that you made to research the historical context for Duchamp’s alleged “Paris Air Medical Ampule.”

Despite Duchamp’s contention that his objects were mass-produced readymades, the fact remains that no exact duplicate exists for any of his productions in the historical record. No scholar has ever found — in any museum catalogue or collection, or dealers’ storerooms — any exact object (urinal, coatrack, hatrack, etc.) that, according to Duchamp’s claims, was mass produced, store bought and readymade. Is this not strange? If an object is mass produced, by definition and logic, the attempt to find a duplicate design should not be analogous to searching for a needle in a haystack or scraping the bottom of a barrel, as has been the case.

So little evidence exists for the art historical othodoxy’s assumption — namely, that readymades are mass produced, and were therefore readily found in stores. Therefore, a reversal of the typical question of evidence about the status of Duchamp’s objects must be proposed. We should be persuaded by, and judge only by, direct evidence any claim that Duchamp objects are, in fact, readymade.

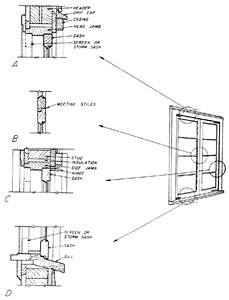

Using three illustrations of infusion devises, your letter lists three criteria met by Duchamp’s ampule in your judgement.

1. A closed vessel for sterilization

2.It can be used as an infusion system (with a bottom to break for connection to a tube)

3.”Convenient apparatus to hang over the patient’s bed because of the glass hook”

Yet when I look at your three illustrations, I fail to follow your conclusion that the Paris Air ampule “combines all three functions in one piece made of the same uniform material.”

Figure 1 does not have a glass hook and, like Figure 2, is safely and securely held by a metal clasp. Therefore the hook and the ampule are separate, not uniform materials as in Duchamp’s ampules. Indeed, Figure 3 is very suggestive — but unlike Figure 1 and 2, which appear to be accurate technical drawings from medical catalogues, Figure 3 with its inclusion of a hanging curtain and rough, hand-drawn quality is unclear. Considering Figure 3‘s earlier 19th century date, this device was replaced by more practical and safe designs shown inFigure 1 and 2. The cylinder form of Figure 2 shares, with the mass-produced ampules developed in France during the first years of the 20th century, a shape that can be safely packed into boxed rows (see my Illustration A of an early 20th century ampule mass-production factory).

click to enlarge

Illustration A

Photograph showing a

factory mass-producing ampules,

France, early 20th century

I have handled many European and American ampules and have “opened” them (see video). It would have been very tricky to attach a hose to the jagged end of an ampule. If indeed a glass hook was ever incorporated (as Figure 3 is unclear), the motion of a patient’s arm would have led to stress on a glass hook that would likely cause it to break or become dislodged. Logic and practicality would lead to the further development of a metal, not a glass hook — as shown by the historical chronology held within your illustrations, beginning with Figure 3, then Figure 1, and Figure 2 as the most historically recent in the series.

But let’s say that you are correct and that Figure 3 was among the early experiments in hand-made infusion devises that Duchamp saw hanging in a pharmacy as an “old pharmaceutical/medical instrument for decoration” (as you write). Is this one-of-a kind and obsolete hand-made infusion ampule to be accepted by us as evidence of Duchamp’s use of a mass produced, easily found, store-bought readymade object?

As to size, I believe that the facts about sizes of infusion balls actually used and made would be extremely important to know. For example, what if infusion ampules — even early custom-made ones — were only more than 125 cc in volume? This fact would further indicate that Duchamp had his own ampule made. Or on the contrary, if you discovered that infusion ball ampules were only made in 35 cc and 125 cc in volume, this would suggest that Duchamp exploited the two standard sizes for his original 1919 and 1941 Boite en Valiseversions, etc. Furthermore, we have testimony by experts that a pharmacist would not have needed unusual skills to convert a mass-produced ampule into a custom-made version similar to Duchamp’s larger 1919 and smaller 1941 Paris Air objects. In fact, Duchamp tells us that he had his 1941 ampules version custom made.

- Click image for video (QT 2.6MB)

- Click image for video (QT 2.6MB)

- Click image for video (QT 2.0MB)

- Demonstration of the

breaking of two antique

ampules at the Art Science

Research Laboratory, NY

- More contemporary ampule

(with thicker glass)

- Display of various antique

ampules at ASRL, NY

I believe that the question of Duchamp’s readymade ampule is very much aided by your research, but must still continue! I would love to find out more about infusion devices. If, in fact, infusion balls were “available in a great variety of sizes for different medical indications,” evidence and images of mass-produced infusion balls matching Duchamp’s Paris Air (1919) should readily be found, and should now be in the historical record in a duplicate form, not just as resemblances. A duplicate of Paris Air (1919) (alas, for people who want to believe in readymades) has not yet been found. We may be facing another Loch Ness monster or Big Foot. People will believe that Duchamp’s Paris Air (1919) ampule was a mass-produced readymade even in the face of little or no evidence.

Dear Tout-Fait,

This question is in my mind and it drives me crazy…

Is the Bicycle Wheel a readymade?

One of my first contacts with the work of Marcel Duchamp was an interview he gave (in French) in the late 60s. He explained very well what the idea behind a readymade is. He also explained the process that led to the Bicycle Wheel.

I remember that he said he used to live in a small apartment in Paris and he wanted to have a fire to warm the place, and also because it would have been nice to have a fire in this small apartment. As he didn’t have any “cheminee de coin,” he couldn’t have any fire. He came up with the Bicycle Wheel on the “tabouret” because moving the wheel reminded him of the movement and sound of a fire. Knowing that, I was a bit confused, as that could mean that the Bicycle Wheel‘s purpose is to “imitate” a fire.

When Miro takes two plates, a rock and a rack and places them together so that they look like a strange personnage, no one says it is a readymade. And I agree. Its purpose is to imitate or give birth to a poetic living form. It is on purpose that this living form looks human in some way (to make it easier for us to understand, maybe).

Anyway, I don’t see so many differences between Miro and his plates and rocks, and Marcel Duchamp and his Bicycle Wheel (I am only talking about the Bicycle Wheel, I understand why the Bottlerack, for example, is a readymade).

I know you might be wondering why I am sending this question to Tout-Fait. Well, you are actually the only person I know who might be able to correct me, and also, it is an opportunity to thank you for the journal. I was very happy to read all of the articles, and really stoned by the news concerning the copies and the 3 Standard Stoppages (!!).

Thanks for the help, and I can’t wait to read the second edition of Tout-Fait.

Dear Rhonda,

Who said, he hated repetition? Exactly — that was the crucial point in staring at Marcel Duchamp’s work for almost one century. The solution does not lie in an agreement of the scholars, but in the deconstruction of this vain palace of interpretations. You are doing the main job. Just looking at the phenomena and describing the context — the context not of the original work, but of our own knowledge. It does not matter what his intentions were, but what we can understand. We all know that Marcel Duchamp will be of importance still in the next decades, much more than all the Picassos. But to realize this, someone had to come and tell us: He did not do the thing as he was declaring and explaining to them. We have to think on our own (Oh, gosh) — that’s the difficult thing. For this reason you are discovering seemingly simple things, such as the “Green Box” surprises and the 3 Stoppages (which really tell us “Stop the pages of art history”). Is it all so obvious, but not for blind men. Our beloved Marcel Duchamp is falling apart — that makes him hateable, but interesting again and again.

Regards,

Prof. Dr. Thomas Zaunschirm

Department of Art History, Essen University, Germany

p.s.- Many congratulations for your online-magazine. One could not wish for more.

Some Duchamp-related postcards from Thomas Zaunschirm:

- Figure 1

- Figure 2

- Figure 3

- Figure 4

- Figure 5

- Figure 6

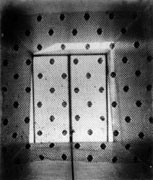

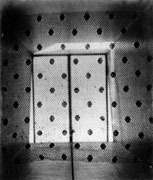

click to enlarge

Illustration 1

Marcel Duchamp,

signed version of

Draft Pistons, 1914

© 2000 Succession Marcel

Duchamp ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

Illustration 2

Marcel Duchamp,

unsigned version of

Draft Pistons, 1914

© 2000 Succession Marcel

Duchamp ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

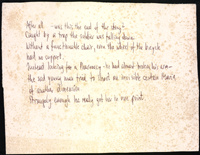

Rhonda Roland Shearer responds:

Your interesting and correct observation of the difference between the Draft Pistons in the Large Glass and his two photographs leads to other evidence of Marcel’s mischievous methods! Duchamp claims to have taken three photographs of fabric blown by air currents through a window (of the three photographs only two remain, as Duchamp claims to have lost the third).(See Illustration #1 and #2.) Richard Hamilton writes that the size of the actual cloth that Duchamp used was 1 meter square. By opaque projector,

click to enlarge

Illustration 3

Enlarged drawing of

the Draft Piston

I enlarged the Draft Piston photographs to 1 meter square. The impossibility of this large 1 meter square size quickly became apparent, as the dots on the lace would then be more than 1 inch in diameter. (See Illustration #3.)Sewn dots depicted in Illustration #4occurring in antique lace are only, approximately, the size of a pencil eraser. Moreover, antique lace of similar type, when scaled to match the lace depicted in Duchamp’s photos, would measure approximately 3¾ x 4¾ inches. Therefore, the lace was not 1 meter square and could not have been in a window curtain (as scholars have assumed). Illustrations #5A, B and Ccompare old lace to one Draft Piston photo scaled to match the size and ratio of actual antique lace. #4C shows an approximation to the actual size of lace that Duchamp used for creating his Draft Piston photography. By further logic, one must also challenge whether the open “window” in the Draft Piston photograph is an actual window or the opening of a miniature box with the 3¾ x 4¾ inch lace hanging in front.

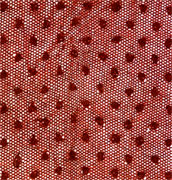

click to enlarge

Illustration 4

Phototgraph showing a

woman veiled in antique lace

As an additional point of interest, I discovered that if one puts the two Draft Piston images side by side into a stereoviewer, an impressive 3-D stereo effect is generated. In light of Duchamp’s interest and his history in creating many original stereoworks, (including stereo-pair images to be seen in stereoviewers included is his 1941 Boîte en Valise miniature museum of his life’s work), the two Draft Pistons photos, working as a stereo pair, is not likely to be accidental. Perhaps the resulting stereo image that one sees from the fusion of the two Draft Piston photos in a stereoviewer is the third Draft Piston image that Duchamp said he “lost” and has now been refound!

- Illustration 5A

- Illustration 5B

- Illustration 5C

- Marcel Duchamp, unsigned

version of Draft Piston

s, 1914 © 2000 Succession

Marcel Duchamp ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

- An old lace, shown

here in red (originally in black)

to better illustrate the contrast

- Comparison by overlaying

the old lace with the

lace in the Draft Pistons

Notes

1. In a telephone conversation of March 10, 1999 between Thomas Girst / Art Science Research Laboratory, Inc. and Richard Hamilton, Mr. Hamilton stated that he only “made the assumption” that the “Draft Pistons” were fabricated by hanging a one-meter-square Net (net curtain or veiling) above a radiator (text in italics quoted from: Richard Hamilton. Collected Words. London: Thames & Hudson, 1982. p. 229). In addition, he mentioned that he “definitely did not get this information from Duchamp” and that he derived his guess regarding the size from the length of the “Standard Stoppages” and by looking at the 1914 photograph.

Hello Tout-Fait,

What a find! I’m an “anartist” and post-grad art history and theory student at the University of Essex in the UK (Dawn Ades and Margaret Iversen are my tutors).

This first issue was tremendous. More please!

Apropos of Rhonda and Stephen’s article on the “Standard Stoppages,” I’m probably not the only Duchampian to notice, also, that the two extant photographs of gauze (hanging over a radiator/in front of a window) bear little relation to the morphology of the “draft pistons” in the Milky Way of the Large Glass. Is this yet another case of Marcel’s methodological mischievousness?

Glenn Harvey B.A.(Hons) M.A.

Dept. of Art History and Theory

University of Essex, UK

William Anastasi responds:

I was pleased to learn that Katherine Dreier has been the subject of a doctoral dissertation. If there is evidence showing that the Tomkins and Marquis accounts of her relationship with Duchamp are off base, adjustments would be welcome. Dr. Angeline states that “correspondence between Dreier and Duchamp does reveal that the Large Glass was indeed accidentally broken, unbeknownst to both Duchamp and Dreier…” This is the explanation given by Duchamp to J.J. Sweeney and Pierre Cabanne. But Duchamp’s marvelous all-weather disclaimers proclaim that Each word I tell you is stupid and false and All in all I’m a pseudo, that’s my characteristic. He was begging posterity to question everything about him, and particularly his statements. I have not succeeded in reaching Dr. Angeline to learn of his sources, but if he is citing letters from the artist, these disclaimers may apply. In any case, (and especially in view of these famous remarks) letters cannot reveal that the Large Glass was accidentally broken, they can only say so.

Marcel Duchamp was clearly creating his own myth. A telling attestation of this can be found in the opening paragraph of William A. Camfield’s Marcel Duchamp: Fountain(Houston: The Menil Collection, 1989). Before embarking on a 180-page dissertation about this enormously influential work from 1917, Mr. Camfield cautions, “We do not even know with absolute certainty that Duchamp was the artist — he himself once attributed it to a female friend…” For all we can tell, Duchamp may have been in collaboration with female friends even at this early date.

William Anastasi

New York, NY

|

Dear Tout-Fait,

Congratulations on an exciting and generally brilliant issue! As a co-editor of an online arts journal (PART, http://web.gsuc.cuny.edu/dsc/part.html) I am impressed with what you have done.

One quibble — the Anastasi article about the Large Glass, while intriguing, unfortunately falls into the same wrongheaded cliches about Katherine Dreier and her relationship to Duchamp that the general literature has perpetuated for far too long. My doctoral dissertation on Dreier tries to present a more even-handed version of their relationship and it is a shame that an otherwise adventurous article would rely on as flippant a source as Tomkin’s biography and simply repeat its glib assertions.

Moreover, the correspondence between Dreier and Duchamp does reveal that the Glass was indeed accidentally broken, unbeknownst to both Duchamp and Dreier, while in storage/transit. Duchamp was in Europe at the time and in fact had to travel to the States expressly to repair the Glass.

The relationship to Jarry still intrigues. I just think it is time that art historians remembered to not sacrifice fact in the make of a theory.

Best Regards,

Dr. John Angeline

The Graduate Center at City University of New York

|

click to enlarge

Figure 1

Sir Roger’s Infusion Apparatus,

A Catalogue of Surgical

Instruments and Medical

Appliances,Allen &

Hanburys Ltd., London, 1938, p. 186

To the Editor:

Stimulated by the article “Paris Air” or “Holy Ampule” by Girst and Shearer in the December 1999 issue ofTout-fait, I conducted some research about the history of infusion medicine. The “Paris Air” ampule used by Duchamp for his artwork combines three main functions of an infusion apparatus. First it can be used as a closed vessel to keep sterilized fluids. Second it can be used as an infusion apparatus. (One simply has to break the far glass ends, connect a tube infusion system to the lower one and gravity draws the fluid into the patient’s vein.) Third it is the most convenient apparatus to hang over the patient’s bed because of its glass hook. Most strikingly, the “Paris Air” ampule combines all three functions in one piece made of the same uniform material.

By using a medical infusion ampule for his artwork Duchamp cites, likely without knowing, from a very interesting part of the history of medicine. Blood letting as a medical treatment has been known since ancient times, but its contrary “infusion” was not tried until Harvey discovered the system of blood circulation in the mid 17th century. In 1656 Sir Christopher Wren wrote the first report about experiments of injections into dogs‘ veins. Although he was a successful medical scientist of his time he changed his profession in 1665 to architecture and built fifty churches in London including the famous St. Paul’s Cathedral. (Remember that the ancient Egyptian god of medicine, Imhotep, used to be a physician and architect as well.) The first report of venous injections into humans was published by Johann Sigismund Elsholtz in Berlin in 1665. Lacking proper materials like small needles and microbiological knowledge like methods of sterilization, the next reports suggesting infusions as a standard medical treatment were not published before the late 19th century. Most of these reports describe different infusion equipment as well as methods of sterilization. Again, it took nearly two to three decades until infusions became a well-established treatment in World War I and World War II.

click to enlarge

Figure 2

Closed Sterile Ampoule,

de l’Asepsie dans la Pratique

Chirurgicale Procedes de Sterilisation,

de Robert & Leseurre, 1930, 141

Closed ampules as a container of pharmaceutical products were first described by Harnack in 1883 . Three years later they were brought into mass production by Limousin in Paris.

Most of the first infusion vessels were open systems like the example of Sir Roger’s infusion apparatus (figure 1). It resembles the shape of the “Paris Air” ampule, but the top end is open and bears a metal hook. Also some closed sterile ampules existed like the one described by de Robert & Leseurre in 1903 (figure 2), which combined a sterile container and infusion apparatus.

The one report about an infusion apparatus which resembles the “Paris Air” ampule best was published by Maurice Boureau in Paris in 1898 (figure 3) . Boureau describes a method of sterilization and the use of what he calls an “Infusion Ball” for infusing “Serum Artificial.” In medical terms “Serum Artificial” is synonymous to “Serum Physiologique” which is also printed on the “Paris Air” ampule and describes a 0.7% – 0.9% Sodium Chloride solution.

click to enlarge

Figure 3

Infusion Apparatus, published

by Maurice Boureau in Paris,

1930, seen from

Zur Entwicklung der Infusion

slösungen in der ersten Hälfte

des 20. Jahrhunderts,

Karin Bischof, Diss. Basel,

1995, p. 307

Some questions still remain unanswered. 1. If Boureau’s report is from 1898 but Duchamp didn’t buy his ampule till 1919, could he have bought an actual “Infusion Ball?” 2. What size is an “Infusion Ball”? Trying to answer the first question one has to bear two conditions in mind: Pharmacists have always been very traditional, therefore using old pharmaceutical/medical instruments for decoration of their pharmacies. Moreover, early in the 20th century the production of pharmaceutical products was individual rather than mass production. The first condition leaves the possibility that Duchamp bought an old instrument. However, because of the second condition, it is still possible that Duchamp bought a new ampule because infusion systems and ampules varied a lot in shape and design. The latter may also be the answer to the second question. If the ampule used by Duchamp was an “Infusion Ball” there is no need to argue about the size. Like most medical/pharmaceutical instruments infusion systems were and are available in a great variety of sizes for different medical indications.

In summary, especially with the knowledge of the Boureau report, it becomes more likely that Duchamp bought an infusion ampule made after Boureau’s description for his “Paris Air” artwork rather than having had one produced by a skilled pharmacist. Why would a pharmacist produce a unique “Paris Air” ampule resembling the “Holy Ampule” when there already existed a pharmaceutical/medical apparatus like Boureau’s “Infusion Ball” which resembled the shape of the “Paris Air” ampule even better?

Yours,

Cand. Med. Tobias Else, Innsbruck, Austria

1. Elsholtz, Johann Sigismund. Neue Clystier Kunst wodurch eine Arzney durch eine eroffnete Ader beyzubringen. Berlin 1665

2. Harnack, Erich. Lehrbuch der Azneimittellehre und Arzneiverordnungslehre. Auf Grund der dritten Auflage des Lehrbuchs der Arzneimittellehre von R. Buchheim und der Pharmacopoea Germanica. ed. II. Hamburg/Leipzig 1883.

3. Limousin, S. “Ampules hypodermiques, nouveau mode de preparation des solutions pour les injections hypodermiques” in Archives de Pharmacie I, 1886.

4. Figure taken from Allen & Hanburys Ltd. A Catalogue of Surgical Instruments and Medical Appliances. London 1938.

5. de Robert & Leseurre. “de l’Asepsie dans la Pratique Chirurgicale Procedes de Sterilisation.”

6. Boureau, Maurice. “La technique des injections de serum artificial,” Diss. Med. Paris 1898. Figure taken from Bischof , Karin. “Zur Entwicklung der Infusionslösungen in der ersten Hälfte des 20. Jahrhunderts,” Diss. Basel 1995

Rhonda Roland Shearer responds:

click to enlarge

Figure A

Marcel Duchamp,

Fountain, 1917

Figure B

Marcel Duchamp, Trébuche

t (Trap), 1917

Figure C

Marcel Duchamp,

Hat Rack, 1917

We truly appreciate the effort that you made to research the historical context for Duchamp’s alleged “Paris Air Medical Ampule.”

Despite Duchamp’s contention that his objects were mass-produced readymades, the fact remains that no exact duplicate exists for any of his productions in the historical record. No scholar has ever found — in any museum catalogue or collection, or dealers’ storerooms — any exact object (urinal, coatrack, hatrack, etc.) that, according to Duchamp’s claims, was mass produced, store bought and readymade. Is this not strange? If an object is mass produced, by definition and logic, the attempt to find a duplicate design should not be analogous to searching for a needle in a haystack or scraping the bottom of a barrel, as has been the case.

So little evidence exists for the art historical othodoxy’s assumption — namely, that readymades are mass produced, and were therefore readily found in stores. Therefore, a reversal of the typical question of evidence about the status of Duchamp’s objects must be proposed. We should be persuaded by, and judge only by, direct evidence any claim that Duchamp objects are, in fact, readymade.

Using three illustrations of infusion devises, your letter lists three criteria met by Duchamp’s ampule in your judgement.

1. A closed vessel for sterilization

2.It can be used as an infusion system (with a bottom to break for connection to a tube)

3.”Convenient apparatus to hang over the patient’s bed because of the glass hook”

Yet when I look at your three illustrations, I fail to follow your conclusion that the Paris Air ampule “combines all three functions in one piece made of the same uniform material.”

Figure 1 does not have a glass hook and, like Figure 2, is safely and securely held by a metal clasp. Therefore the hook and the ampule are separate, not uniform materials as in Duchamp’s ampules. Indeed, Figure 3 is very suggestive — but unlike Figure 1 and 2, which appear to be accurate technical drawings from medical catalogues, Figure 3 with its inclusion of a hanging curtain and rough, hand-drawn quality is unclear. Considering Figure 3’s earlier 19th century date, this device was replaced by more practical and safe designs shown in Figure 1 and 2. The cylinder form of Figure 2 shares, with the mass-produced ampules developed in France during the first years of the 20th century, a shape that can be safely packed into boxed rows (see my illustration A of an early 20th century ampule mass-production factory).

click to enlarge

Illustration A

Photograph showing a factory

mass-producing ampules,

France, early 20th century

I have handled many European and American ampules and have “opened” them (see video). It would have been very tricky to attach a hose to the jagged end of an ampule. If indeed a glass hook was ever incorporated (as Figuer 3 is unclear), the motion of a patient’s arm would have led to stress on a glass hook that would likely cause it to break or become dislodged. Logic and practicality would lead to the further development of a metal, not a glass hook — as shown by the historical chronology held within your illustrations, beginning with Figure 3, then Figure 1, and 2 as the most historically recent in the series.

But let’s say that you are correct and that Figure 3 was among the early experiments in hand-made infusion devises that Duchamp saw hanging in a pharmacy as an “old pharmaceutical/medical instrument for decoration” (as you write). Is this one-of-a kind and obsolete hand-made infusion ampule to be accepted by us as evidence of Duchamp’s use of a mass produced, easily found, store-bought readymade object?

As to size, I believe that the facts about sizes of infusion balls actually used and made would be extremely important to know. For example, what if infusion ampules — even early custom-made ones — were only more than 125 cc in volume? This fact would further indicate that Duchamp had his own ampule made. Or on the contrary, if you discovered that infusion ball ampules were only made in 35 cc and 125 cc in volume, this would suggest that Duchamp exploited the two standard sizes for his original 1919 and 1941 Boite en Valiseversions, etc. Furthermore, we have testimony by experts that a pharmacist would not have needed unusual skills to convert a mass-produced ampule into a custom-made version similar to Duchamp’s larger 1919 and smaller 1941 Paris Air objects. In fact, Duchamp tells us that he had his 1941 ampules version custom made.

- Click image for video (QT 2.6MB)

- Click image for video (QT 2.6MB)

- Click image for video (QT 2.0MB)

- Demonstration of the

breaking of two antique

ampules at the Art Science

Research Laboratory, NY

- More contemporary

ampule(with thicker glass)

- Display of various

antique ampules at ASRL, NY

I believe that the question of Duchamp’s readymade ampule is very much aided by your research, but must still continue! I would love to find out more about infusion devices. If, in fact, infusion balls were “available in a great variety of sizes for different medical indications,” evidence and images of mass-produced infusion balls matching Duchamp’s Paris Air (1919) should readily be found, and should now be in the historical record in a duplicate form, not just as resemblances. A duplicate of Paris Air (1919) (alas, for people who want to believe in readymades) has not yet been found. We may be facing another Loch Ness monster or Big Foot. People will believe that Duchamp’s Paris Air (1919) ampule was a mass-produced readymade even in the face of little or no evidence.

Figs. A, B and C

© 2005 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris. All rights reserved.

Dear Drs. Gould and Shearer,

Thank you for your interesting article in the December issue of Natural History. It led me to an alternative interpretation of his boat/deckchair illusion using the notion of a cross-section, which is implicit in the passage from Flatland that you quoted.

Imagine three spheres in space. One can obtain a 2-dimensional representation of them by taking a cross-section, that is, slicing through them with a plane. The result would be a collection of circles in the plane. Depending on which plane one chooses, the relative sizes of the circles will be different; as one moves the plane, they will grow and shrink in the way Abbot describes.

Now imagine three objects in 4-space (three 4-spheres, for example). One can obtain 3-dimensional representations by slicing them with a 3-dimensional space (a “hyperplane”) and, again, depending on which hyperplane one chooses the objects will have different sizes. If the objects are 4-spheres, then the 3-dimensional hyperplane slice will be a collection of ordinary 3-dimensional spheres of different sizes. And again, as one moves the hyperplane around the spheres will grow and shrink. Thus, rotating Duchamp’s postcard achieves the optical illusion of this growing and shrinking process by causing one to reassess the sizes of the objects. Duchamp invites one to replicate the growing and shrinking process involved in moving the hyperplane around by holding the card vertically and “considering the optical illusion produced by the difference in their dimensions.”

This interpretation may capture more precisely the mathematical intent of his words.

Sincerely,

Bill McCallum

Department of Mathematics

University of Arizona (Tucson)

To the Editor:

In their essay on a note by Marcel Duchamp about the fourth dimension (Natural History, 12/99-1/00), Stephen Jay Gould and Rhonda Roland Shearer emphasize the fact that no other previous Duchamp scholar has ever noticed that the text of this particular note relates to the image of three boats in a landscape that appears on its verso. Although they go on to explain that there are various reasons for why this observation had not been made before — without explanation — they specifically single out my writings as an example of a Duchamp scholar who missed this very point.

This is a perfect example of biased and prejudicial scholarship. Since it was employed by a Darwinian like Gould, it is difficult to resist comparing his actions to that of natural selection, one that, in this case, functions within the ongoing evolution of his and his wife’s indomitable quest to find hidden meanings in the work of Marcel Duchamp. If these writers were really going to be fair in assessing my powers of observation, after having cited my description of this note, they would have gone on to quote the very next sentence of my writings: “Although it has been assumed that these paper fragments were selected arbitrarily and that they bear no relationship to the subject of the notes themselves, at least one note referring to the ‘legs of the [Chocolate] Grinder’ appears, appropriately, on the verso of a torn fragment of candy wrapping advertising the town of ‘Hershey, PA.'” (The Mary and William Sisler Collection, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1984, p. 143). In the note discussed by Gould and Shearer, I did not notice a relationship between the subject of the fourth dimension and the image appearing on its verso for one very specific reason: I am not wholly convinced that there is one (not when I wrote about these notes over fifteen years ago, nor even now after having read their elaborate argument).

First of all, these authors claim that “Duchamp’s object is not, in fact, a commercially produced postcard but an original painting, almost surely by Duchamp himself.” This is a perfectly reckless assertion, particularly since it is made without a single shred of supporting evidence. Stylistically, the image bears no relationship whatsoever to any other work by Duchamp from this period, unless, of course, Duchamp feigned an artistic style totally foreign to his own artistic sensitivities (even if this were the case, then we are presented with no reasonable explanation for why Duchamp would have employed such a strategy). The authors then point out that on the verso of this image, “a vertical line in the middle and four horizontal lines to the right” were “inked in by hand” to “mimic the address guides of a normal postcard.” These lines would prove critical, for according to the authors, they provide a clue that the image on the other side must be rotated in order to be understood for its fourth dimensional message. But even here, how can we be sure that Duchamp drew these lines? I — for one — doubt very much that he did.

I share the belief that Duchamp’s note was written on a “pseudo-postcard,” that is to say, a watercolor executed on a relatively thick piece of drawing paper and cut to resemble the size and format of an ordinary, commercially-produced postcard. But it is hardly necessary to prove that Duchamp himself physically rendered this image; simulated, one-of-a-kind postcards of this type can still be purchased on the streets of Montmartre to this very day, affording tourists the option of sending their correspondents relatively inexpensive original works of art. In order to make the function of their product clear, it is usually the artist who draws the address lines on the verso of the image as well as.

It is, of course, entirely possible that Duchamp might have noticed a casual resemblance between the three rather poorly-executed boats on the facing side of this card and an overhead view of deckchairs, causing him to muse on the subject of the fourth dimension (just as I had earlier noticed that an advertisement for Hershey’s Chocolate inspired Duchamp to write about the leg of the Chocolate Grinder). But I do not — for a moment — believe that he drew this image to serve as an illustration of his ideas. The boats on this card bear a resemblance to one another not because their proportionate sizes were meant to illustrate a concept of the fourth dimension, but simply because after having drawn literally hundreds of similar boats, for the sake of convenience and expediency, the Montmartre artist repeated the same pattern that — by then — had been engrained in his visual memory.

Lastly, I find it preposterous that in such a highly respected publication devoted to the sciences, the authors are allowed to refer to their relatively-minor observation as a “discovery.” Indeed, the following claim is highlighted in the text: “Shearer discovered the key as we indulged in our favorite pastime: playing mental chess with Duchampian puzzles.” If these authors see only puzzles in Duchamp, then I am afraid they shall remain forever blinded to his most important message. In my opinion, they would be better guided by following the advice contained in one of his most memorable statements: “There is no solution because there is no problem.”

Francis M. Naumann

Dear Professors,

I am only vaguely familiar with the concept of the fourth dimension, and your fascinating essay in the January Natural History will encourage me to investigate it. I believe that you are away of some points that I would like to make and ignored them for brevity’s sake, but let’s see.

One of the overriding proposals of the essay was that we cannot view both sides of an object at the same time. Actually there are several ways that this would be accomplished, the simplest, by the used of a septum and mirrors. A more easily-understood way would be to use two fiberoptic endoscopes, each focused on opposite sides of the object, and each viewed simultaneously by opposite eyes as follows (I’ll use a sphere since my drawings of cubes, viewed on opposite corners, appear confusing).

Note, however, that even though we have provided the brain with the simultaneous view of each side of the object, we have not enhanced the three-dimensional view into a fourth dimension. In fact, with no common detail visible to each eye, the percept is either diplopia if the two sides are too dissimilar, or fusion to a single, flat, two-dimensional disc.

The hand has many individual tactile sensors, which contribute to the 4-dimensional mental image of the penknife that the brain is programmed to interpret. If A-square were a Cyclops, he could not have appreciated the new stereoscopic view provided by the sphere; there are monocular clues to depth, but the 3-dimensional appreciation requires binocularity. Similarly, we are limited by the bilaterality of the visual system to a maximum view of three dimensions. By my calculation, four eyes, on flexible stalks, and the necessary brain functions to interpret the images would be the minimum requirement. (But you know, I really do not have any trouble visualizing this when I conceive of it this way, with four eyes and four endoscopes, perhaps because of my training. And I do recognize that we are minimizing the spatial elements in these examples).

There are two issues that I need to investigate regarding the 4th dimension. First, why is it necessary to understand it in visual terms, particularly human vision? Is this just a prejudice based on our human emphasis on vision? Why isn’t the hand/penknife example adequate, as it appears to be to me? Secondly, is this all very simplistic? Do we also have to incorporate a view from both insides as well as from the outside of an object to attain appreciation of the fourth dimension?

I better go dig out my old textbooks or hit the library.

Sincerely,

James L. Schmitt, O.D.

Muncy, Pennsylvania

|