Dada is Dead, Beware of the Fire! An Interview with Huang Yong Ping

On the afternoon of October 5, 1986, works exhibited in the “Xiaman Dada” exhibition at The Cultural Palace of Xiamen, the coastal province in southern China, were set on fire, turning to ashes by a sheer breathe of the autumn breeze. “The show no longer exists,” proclaimed the initiator of the group, Huang Yong Ping, in the accompanying statement commenting upon the burning event that day. “The way one treats one’s work of art marks the degree to which the artist is willing to liberate himself… even undergoing an irrational process.” Huang Yong Ping intended to undermine the importance artists place on the value of their works throughout the entire history of Chinese Art.

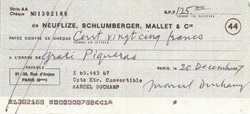

Among the first generation of avant-garde artists active in the 1980s, Huang Yong Ping, like his fellow artists of the same generation, seeks to demolish the tyranny of the doctrine of Social-realism by promoting free expression. He has lived and worked in Paris since participating in the “Les Magiciens de la Terre” exhibition at the Paris Museé National d’Art Moderne de Centre Georges Pompidou” in 1989. He regularly participates in international exhibitions, including “Hommages à Marcel Duchamp” at the Ecole Régionale des Beaux-Arts, Rouen, France, in 1994; the “Hugo Boss Prize 1998” at The Guggenheim Museum of New York; “Inside Out: New Chinese Art” at the PS1 and Asia Society Galleries, New York; the installation project for the French Pavilion in 1999 Venice Biennale.

In recent decades, Chinese artists have emerged on the international art scene generating interest and engaging in a multicultural dialogue regarding the re-thinking of meaning as well as that of the global structure. In the case of Huang Yong Ping, he takes Duchamp as one of the strategic elements–as sign–aiming at deconstructing art and traditional value for the new. His approach is a negation process deriving from ancient Chinese philosophy by connecting Dada with Zen–borrowing Duchamp to go against Duchamp–for the re-thinking of text. From my interview with Huang, the acknowledged impact of Duchamp on the conceptual development of his art enables us to speculate on the range of issues the artist has tackled throughout the chronological and geographic changes of his life. By means of Huang’s cross-cultural and cross-historical approach, in the end, the aesthetic impact we experience from his works eventually validates the hybridity of cause and effect. The linear perception of historical determinism no longer qualifies as the single answer to homogeneity and difference in our environment.

Rewriting example 1:

When you have no cane, I will take it away.

When you have one, I will give you one.– Zen Buddhism(1)

TF: Being an active member of the Avant-garde Art Movement during the mid-1980s [a.k.a. the “85 Movement”] and the leader of the ‘Xiaman Dada’ group, please outline this influential movement, and its contribution to the overall development of contemporary art in China?

HYP: Looking back at the ’85 Mei-Shu (Art) Movement,’ it was more like the ‘Peasants’ Reform.’ As I graduated from the Fine Art Academy of Zhejiang, and was deployed back to my hometown, Xiaman, to teach art, I was already seen as member of the rebellion. At that time, many revolts had begun impulsively throughout the nation. This countrywide phenomenon generated all sorts of liberations and dynamics among various circles. More importantly, it was a group of young editors of art journals in Beijing, Wuhan, and Nanjing which introduced these personal and underground acts to the general public and the society. In the long run, these connections disseminated and caused the pivotal effect.

TF: What would be the goal and meaning of this movement to the history of art in China? And, its association with the Western Avant-Garde?

HYP: The meaning of this fractal history would be that it had surpassed the boundary of Social-realism in the society, awakening a sense of individual vitality among the young generations. And then, we expect to associate this vitality with Western Avant-Garde, although this association seems somewhat abstract, however superficial. In other words, the movement is to include China’s contemporary art into a grand background of the “Globalization,” rather than just self-murmuring in the given political rhetoric.

TF: Under what circumstance did you first learn of Marcel Duchamp? And to what extent has he influenced your aesthetic concerns?

HYP: Back then China did not have any publication on Marcel Duchamp at all. I learned about him through any materials that I could possibly acquire. The most influential book to me is the Chinese edition of Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp by Pierre Cabanne, published either in Taiwan or Hong-Kong. I borrowed the book from the library, and made copies to circulate among my fellow friends. I even carried the copy with me when I had to leave the country in 1989. In 1994, this copy became an essential part of my installation work (to be mentioned below). What interests me about Duchamp are the qualities, such as the ambiguity of languages (his use of puns), the ability to transform a stone into gold (alchemy), and his hermetic life style. It is also very Eastern. Yet, when I was drawn into his art in the beginning; I was also against him. In 1988, I wrote an essay entitled “Duchamp Stripped Bare by People, Even: Rewriting Case 5, or Duchamp Phenomenon Study.” I thought that such a study was a pure joke on theories, without any substantial quality except gesture and rhetoric. As a matter of fact, the more one is attempting to study, the more ridiculous one will become.

TF: In 1986, you brought the ‘Xiaman Dada’ into public attention. By definition, how does the concept of “Dada” derive, and differ from that of the Western context?

HYP: There is seventy years separating 1916 and 1987. It is in no way to evaluate history of Western Art and that of China in a parallel or linear way. In 1986, when I initiated Dada in Xiaman, I meant to pinpoint the “85 Mei-Shu Movement.” I felt responsible of imposing the “non-,” or “anti-” conception, in order to promote a kind of skeptical and critical attitude. I didn’t appropriate “Dada” in a strict sense. To be honest, I was not interested in those artists who were labeled as Dadaists except Duchamp. As an alternative, I would rather like to include Yves Klein, John Cage, and Joseph Beuys into this category which I identify as “Dada is Zen, Zen is Dada.” You can also refer to two papers I wrote during the period–“Xiaman Dada: A Form of Post-modernism,” and “Pointing to the Complete Void: Dada and Zen.”

click to enlarge

Figure 1

Huang Yong Ping,

Big Roulette, 1987

Figure 2

Huang Yong Ping,

Small Portable

Roulette, 1987

TF: The Roulette Series (1986-88) (Figs.1 & 2) has obvious allusions to Duchamp as you take on the roulette wheel to construct “Non-expressive painting” by chance. Although the approach and concept are undoubtedly Duchampian, you adopted I-Ching to design the rules for the game. It turned out to be the key to the entire creative process through which a different thinking is given. Duchamp negates the retinal effect of the visual aspect; you appropriated the roulette wheel to replace the artist’s hand for non-expressive painting. In reality, the abstraction of the resulted painting is self-evident, albeit it is the end product of the artist’s indifferent act. Are contradiction and irony part of your intentions, or more of a surprising effect?

HYP: Yes, completed by turning the roulette wheel to determine the color, strokeand its pictorial arrangement (Fig. 3), Non-Expressive Painting (Fig. 4) at first glance indeed resembles abstract expression, so to speak. It is not only self-contradictory but also ironic, almost ridiculous. I carefully arranged a network of conventions, excluding psychological impulse. Turning the wheel entirely based on the pre-designed mechanism, as if a student imitates from the given materials. As a result, the painting appeared to be automatic, and impulsive. It is perfectly proving my original thinking–the painting as the consequential entity in its own right is divorced from the initial intention of the author, and does not necessarily have direct association with it.

click images to enlarge

Figure 3

Photograph of Huang Yong Ping turning the Roulette

for Non-Expressive Painting

Figure 4

Huang Yong Ping, Non-Expressive Painting, 1988

YLC: You also made Repacking Catalogue: It is Most Easy to Set a Beard on Fire (1986-87). (Fig. 5) Borrowing a concept in which Dechamp appropriates works by masters from the history of art, Repacking Catalogue seems to be the counterpart of L.H.O.O.Q. (Fig. 6).

click images to enlarge

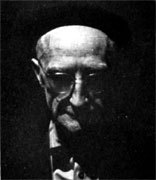

Figure 5

Huang Yong Ping,

Self-Portrait?

da Vince? or Mona

Lisa?, 1986-87

Figure 6

Marcel Duchamp,

L.H.O.O.Q., 1919

HYP:In the mid-1980s, it was impossible to find a Duchamp catalogue in China. Nevertheless, catalogues by masters from the classical era are everywhere. There are four or five similar works in the Repacking Catalogue series. After finishing Set a Beard on Fire, I said, “You see, da Vinci is still perfectly relaxed even his beard has caught fire.” Accidentally, I placed the cheap publication against the light. The images on both sides of the catalogue overlapped–the image of da Vinci’s Self-Portrait overlapped with that of the Mona Lisa on the opposite page. After the painting is finished, friends discovered that “It looks just like you.” Thus, I titled the work as Self-Portrait? da Vinci or Mona Lisa?

TF: You began the Dust Collecting Project in 1987. (Figs. 7 & 8) What is the content, process and the result of this particular project?

click images to enlarge

Figure 7

Huang Yong Ping, Dust Collecting

Project, 1987

Figure 8

Huang Yong Ping,

Dust Collecting Project, 1987

HYP: There are four pieces in the Dust Collecting Project series: the first one is the white canvas collecting greasy dirt and dust on the kitchen stove; the second is a roll of white paper pulled out from a self-made wooden box letting dust fall through time; the third piece is a canvas receiving dust from trimmed pencils by students in my drawing class at a high school where I used to teach; the last one is a glass bottle collecting dirt from the cleaning ritual at New Year’s Eve. The last two are missing. They are supplementary to our daily life, not worth to pay special attention to.

TF:What was the reaction from the official and the public to the “Xiaman Dada” exhibition?

HYP: “Xiaman Dada” events did not attract huge crowds. During 1986 and 87, social climates in China kept changing recklessly. When we set the works on fire in the 1986 “Xiaman Dada” exhibit in front of the Cultural Palace of Xiaman, China, only some forty to fifty people participated. The “Event” exhibition at the Museum of Fine Art of Fujian lasted only two hours before it was being forced to shut down. However, albeit these uprisings happened only in small circles in the beginning, they were able to disseminate out eventually.

Rewriting example 4:

Art is dead, yet it is still happening;

art is happening, but it is dead. – Anonymous(2)

TF: Before leaving China, the inspiration from Dada is a kind of resonance from a distance (historically, culturally, and socially). Just out of curiosity, has the geographic and cultural relocation ever affected your reading of Duchamp?

HYP: I think what you mean is if in fact it is distance that evokes resonance; the change of distance would in turn create alienation. This perhaps relates with what I used to mention in 1991–the strategy of “Using the East to fight the West; Using the West to fight the East.”

TF: From 1997 to 1998, you finished Thousand Armed Buddha and The Saint Leaned from a Spider to Weave a Cobweb. Before we talk about these works, have you also made any work inspired by Duchamp before 1997?

before 1997?

click images to enlarge

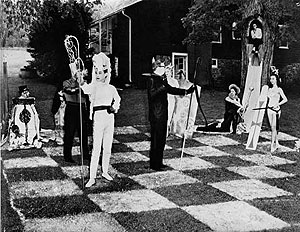

Figure 9

Claude Yutault,

Movable Chess

Board, 1985

Figure 10

Huang Yong Ping,

Water Jar, 1992

Figure 11

Huang Yong Ping,

Water Jar, 1992

click to enlarge

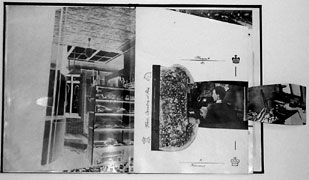

Figure 12

Huang Yong Ping,

108 Answers,

1993 (the 10th, 65th,

74th, 58th, and

59th Answers)

HYP: After 1989, there are several works associated with him. As a result of the geographical change, my reading approach has shifted as well. In 1992, Jean-Hubert Martin (the curator for the 1989 exhibition “Magician of the Earth”) organized the “Résistance” exhibition at the WATARI-UM Museum in Japan. Four artists took part in this show, including Duchamp’s Chess Board, Green Box, and Coatrack. Behind the wall where displays of Duchamp’s Chess Board, the French artist Claude Yutault installed his Movable Chess Board of 1985 (Fig. 9). I presented a giant tank filled with water on top of the Movable Chess Board in a wide-opened courtyard. I intended to imply the scene in which Marcel Duchamp and May Ray played chess and then were washed away by water in 1942 (Figs. 10 & 11). It has to do with the “Food Chain” between artists and their works. In the 108 Answers of 1993(Fig.12), I incorporated six components from works by Duchamp, such as hair, a comb, a lock, a lamp, a urinal, and dust, with a well-known book of Chinese herbal medicines, P’en-Ts’ao Kang-Mu, by Li Shin-Chen (1590-96) from the Ming Dynasty. I attempt to tackle the possible interpretation of substance in different cultures and eras. In the Trois Pas – Neuf Traces project of 1993 at Ateliers d’Artistes de la Ville de Marseille, France, Duchamp’s Torture-Morte (1959) is transformed into The Foot of Christ (Figs. 13, 14, 15, 16).

click images to enlarge

- Figure 13

Huang Yong Ping,

Drawing and Study for

Trois Pas – Neuf

Traces, 1995 - Figure 14

Huang Yong Ping,

Floor plan for Trois

Pas – Neuf Traces, 1996

- Figure 15

Huang Yong Ping, Trois

Pas – Neuf Traces, 1995

(Installation view) - Figure 16

Huang Yong Ping, Trois Pas –

Neuf Traces, 1995

(Installation view)

click to enlarge

Figure 17

Huang Yong Ping,

Thousand Armed

Buddha, 1997

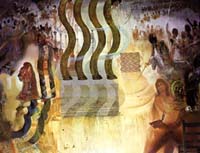

TF: You installed a giant bottle dryer with various objects of our daily life attaching to the end of the racks in the “Muenster Installation Project” of 1997. Through the outsized form and dancing objects, the relation between the signifier and the signified becomes evident. First of all, why the title Thousand Armed Buddha (Fig.17)Any indication in terms of the selection of the hanging objects?

HYP: Bottlerack is commonly perceived as “erotica” in terms of the protruding rack, as if it is an invitation for the bottle opening. I borrow this original meaning, if any, and transform the object into an Eastern Thousand Armed Buddha. Fifty “arms” grasp fifty objects on the enlarged bottlerack. Some are symbolic objects deriving from Buddhism, such as a steel bowl, a Goddess of Mercy bottle, a small pagoda, a spiral sea shell, a lotus flower, a snake, etc. Others are our daily objects incongruent with religious context, including a broom, a feather duster, and a cane. Hence, the indifference and estrangement of the ready-made is disenchanted and concealed by multiple symbols. This sculpture juxtaposes contexts of two cultural backgrounds, allowing them to correct each other.

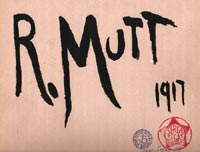

TF: In 1917, the Blind Man journal published an article entitled “Buddha of the Bathroom” after Duchamp’s Fountain was rejected by the jury of the Society of the Independent Artists, commenting upon the irony of the event. It is intriguing you also take on Buddha as an East-meets-West connection.

HYP: I am not sure about the association between Fountain and Buddha. If in fact there is a formal similarity between Fountain and Bottlerack, it must be the narrow-to-wide shape from top to bottom, resembling a “seated Buddha.” Therefore, if Fountain transforms into a meditating Buddha, then Bottlerack is naturally a “Thousand Armed Buddha.”

click to enlarge

Figure 18

Huang Yong Ping,

The Saint Learned from

a Spider to Weave a Cobweb, 1994

Figure 19

Huang Yong Ping,

The Saint Learned

from a Spider to Weave

a Cobweb, 1994

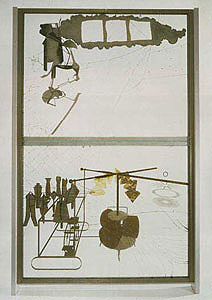

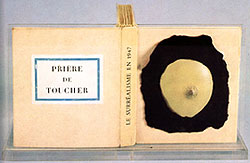

TF: Can you describe The Saint Learns from a Spider to Weave a Cobweb (1998) (Fig. 18)? It is said that when you were in the process of installing, it reminded you of Duchamp as well, especially the projected shadow, and the hanging approach?

HYP: The title, The Saint Learned from a Spider to Weave a Cobweb, derived from the wisdom of a Taoist philosopher. In 1994, I had created a work bearing the same title for The “Hommages à Marcel Duchamp” exhibition organized by the Fine Art Academy of Rouen. It has a direct association with Marcel Duchamp. A live spider crawls slowly on a transparent glass panel, on the bottom of a lampshade-like bamboo cage. The Moving shadow of the spider is projected on a photocopy of Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp I placed on the table directly beneath the bamboo cage (Fig. 19)–is the spider reading? In the meantime, the spider shadow resembles a two-dimensional projection of the three-dimensional hatrack! I also used the same title for the 1997 project at the Galerie Beaumont Iro, Luxembourg, with some changes. Instead of the live spider, in a giant vertical cobweb the projected shadow of a coatrack is transformed into a multiple-armed chair. The chair in the center returned to the traditional Master Armchair in the 1998 version of the same work in New York.

Notes

1.Cited from Huang Yong Ping, “Duchamp Stripped Bare by People, Even: Rewriting Case 5, or Duchamp Phenomenon Study,” 1988.

1.Cited from Huang Yong Ping, “Duchamp Stripped Bare by People, Even: Rewriting Case 5, or Duchamp Phenomenon Study,” 1988.

2. Cited from Huang Yong Ping, “Duchamp Stripped Bare by People, Even: Rewriting Case 5, or Duchamp Phenomenon Study,” 1988.

2. Cited from Huang Yong Ping, “Duchamp Stripped Bare by People, Even: Rewriting Case 5, or Duchamp Phenomenon Study,” 1988.

![Faux-Vagin [

false Vagina]](/issues/volume2/issue_4/interviews/gervais/images/03_small.gif)

![Faux-Vagin [false

Vagina]](/issues/volume2/issue_4/interviews/gervais/images/04_small.jpg)