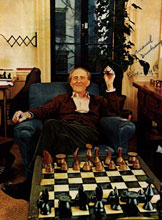

Duchamp the Chess “Idiot”

Damisch: You remember Duchamp’s famous print of two chess players . . . [I was furious] that idiot, Duchamp! He just managed to get $2,000 off me for his Chess Association and in exchange he gave me this horrible etching of chess players. . . . [And he] said that Art no longer had any internal necessity; it was now a pure convention!

In 1961 Marcel Duchamp organized an auction of artworks to raise funds for the American Chess Foundation and asked many of his contemporaries to contribute works. The ‘horrible etching’ which Damish purchased, a reproduction of his 1911 cubist painting The Portrait of Chess players (Fig.1), is part of a largely incommensurate aspect of Duchamp’s historical and artistic legacy: Chess. Damisch’s response to this work is like that of other art historians to his entire involvement in the game. Most commonly, Duchamp’s involvement in chess is expressed as incomprehensible, or simply ignored.Click to EnlargeFigure 1

Marcel Duchamp,

The Portrait of Chess Players, 1911

Popular historical representations tell that in 1923, after the completion of The Large Glass (Fig.2), he quit art to play chess.

Nevertheless the connection between chess and Duchamp’s greater artistic agenda is fundamental to understanding him as an historical figure.

Damisch begins a critique on Duchamp as chess player, The Duchamp Defense, with an outline of his chess career, primarily to construct a ‘narrative’ of his achievements in the realm of chess.

The reading of this is impressive. However, Damisch then poses the questions, how does such a narrative serve in attempting to understand Marcel Duchamp? What is the purpose of such a narrative? In developing an understanding of Duchamp, the artist, what is the purpose of understanding Duchamp the chess player? Damisch says that this narrative should not just be told for the love of a story but to establish the value chess was held by Duchamp. figure 2

figure 2

Marcel Duchamp, Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even [a.k.a. The Large Glass], 1915-23, Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Above all is his belief that [Duchamp] was never more interested in chess than after he had ceased being interested in painting.

This narrative shows that Duchamp’s involvement in chess was not a side-line interest but rather Duchamp’s dedication to chess was with “all the ambition and single minded passion of a professional.”

Yet, as Damisch states, this passion that would dominate his time and intellect for over twenty years of his life “was no more than a game.”

Thus if the aim is to understand his art work it has been common practice to dismiss such an investigation in Duchampian chess as an incongruous aspect of his life. Tomkins, who has written extensively on Duchamp, offers that,

Although chess claimed a great deal of the energy that had been formerly devoted to his Large Glass, the usual statement that he abandoned art for chess is misleading. In fact, one of the essential facts about it is that while he has successfully avoided playing the role of artist since 1923, he has never left the art world.

Tomkins points out that the art world has used a blunt instrument to separate aspects of Duchamp’s life. The ‘quitting’ one activity and taking up of another is symptomatic of the way historical figures are commonly represented. Furthermore, historical methodology has placed restrictions upon how Duchamp has been investigated and subsequently represented. It is these assumptions of art historians that have led to the creation of a coherent art narrative of Duchamp’s life and work that has not allowed chess to disrupt or to inform it. Duchamp’s engagement in a variety of intellectual disciplines disrupts such a clear cut understanding of Duchamp as an artist. Such an approach restricts the historical and critical understanding of Duchamp by considering his activities outside the paradigm of art, as peculiar, inconsistent and irrelevant. As ‘an-Artist’ Duchamp allowed diverse and distinctly different institutions to converge, to interrelate, informing a complex philosophical understanding of art and the intellectual milieu in which he was living.

The Histories of Marcel Duchamp as Chess Player

. . . comparatively little has been written about Duchamp’s chess as a form of artistic activity, how it relates to his other artistic interests, and what it reveals about his attitude to art in general. A few writers have commented on these matters, but their views tend to be underdeveloped and are often highly speculative. Roger Cardinal summed it up when he remarked that “nobody has entirely assessed the significance of chess in Duchamp’s career.”

When attempting to address the nature of chess in the life of Marcel Duchamp one is met with many contradictions. Even from within chess there is debate over Duchamp’s approach to the game and has also failed to bridge the theoretical distance in an attempt to reflect upon his art. Theorists have attempted to determine Duchamp’s playing style through a comparison of the complexities in conservative Classical chess play and Avant-garde Hypermodernism. Yet, due to misunderstandings concerning Hypermodernism in chess and of Dada in art, we will see how some, like Keene, Humble & Le Lionnais, have drawn various conclusions about Duchamp the chess player.

It is tempting for the art historians, like Arturo Schwarz, to adopt a systematic approach when writing about Marcel Duchamp and to create a theory through which all of his work can be seen. However one must be wary of theories that claim to unlock the system or pattern behind Duchamp’s work. For such dominant or meta theories have greatly affected how aspects of Duchamp’s life and works are understood. Francis Naumann in his article titled “Marcel Duchamp: A Reconciliation of Opposites,” warns that any attempt to formulate Duchamp “would be – in the humble opinion of the present author – an entirely futile endeavor .“Francis Naumann suggests that Duchamp gave his response to those attempting to unlock the mystery when he said “There is no solution, because there is no problem.” In understanding the nature, role and significance of Duchampian chess, one needs to see beyond the problem / solution dilemma and operate at a different cognitive level involving multiplicity and complexity. This thesis aims to demonstrate a multiplicity of the complex relationships between Duchamp as artist and as chess player. The importance for this approach, as Naumann states, is that Duchamp himself moved through a number of contemporary artistic styles and each time developed a unique approach of self consciously “defying convenient categorization.”To support this claim Naumann offers a collection of quotations by Duchamp from a 1956 interview with James Sweeney emphasizing the importance of change and the defiance in his work to any tradition or “taste.”

‘It was always the idea of changing,’ he later explained, of ‘not repeating myself.’ ‘Repeat the same thing long enough,’ he told an interviewer, ‘and it becomes taste,’ a qualitative judgment he had repeatedly identified as ‘the enemy of Art,’ that is, as he put it, art with a capital A.

Humble asserts that published views on Duchamp’s chess as art are “underdeveloped and often highly speculative is, he suggests, due to the reason that nobody is entirely sure how to understand or to define chess itself. Humble muses that chess players themselves debate whether chess is a game, sport, science, or art.

With this being said, the mystery of chess in the life of Marcel Duchamp is a subject that has often been approached in a formulaic manner. Questions like; “What type of player was Duchamp?,” “What was the role of chess in his life?,” and “What is the relationship between chess and art?” have been presented in a simplistic and minimalistic fashion. One example of this is an article by grand master and chess theoretician Raymond Keene titled Marcel Duchamp: The Chess Mind. In this article Keene discusses Duchamp’s achievements, his associations, his theoretical positions, and attempts to establish a relationship between art and chess. Primarily his analysis focuses upon the nature of Hypermodernist chess praxis and the dada art movement. Keene seeks to show that Duchamp as well as being a Dadaist, was also a hypermodernist chess player and thereby establish that the relationship between chess and art is dada. In this way, Hypermodernism is often equated with dada, yet the similarities have more to do with the look and feel of the game rather than theory. In comparison to Classical or Modern games hypermodernism seems absurd and illogical.

Keene’s theoretical analysis of Duchamp’s chess play dismissed comments made by a chess player and dadaist contemporary of Duchamp’s, Francis Le Lionnais. Le Lionnais defeated Duchamp in 1932 in Paris, and later stated that Duchamp was not a dada chess player, but a player who adopted a conventional, conformist, or classical style of play.

To counter this claim, Keene looks closely at the influence and the similarities between Duchamp and the founder of hypermodernism, Grand master Aaron Nimzowitsch. Keene asserts that Duchamp borrowed a Nimzowitsch opening for the 1927 world Championship. Keene’s theories concerning the relationship between chess and art are convincing. Keene argues that the tactical talent displayed in his love for “paradoxical hidden points” is fundamentally Dada. Keene mirrors Duchamp’s comments that chess was a “violent sport” with that of Nimzowitsch who said “chess was a struggle like that of life.”

Further, Keene shows Duchamp’s continuing dedication to Nimzowitsch. In the course of his research Keene visited Teene Duchamp, Marcel Duchamp’s wife, and found a copy of Nimzowitsch’s Chess Praxis that Duchamp had hand written (over 200 pages).

Keene demonstrates the associations between Duchamp and Nimzowitsch and dispels the comments made by Le Lionnais. Keene establishes a close association between Duchamp and Nimzowitsch, arguing that Nimzowitsch was a hypermodernist and therefore that Marcel Duchamp was one also. Keene’s conclusion is not far off, yet, it maintains an understanding of Hypermodernism that is misleading. Keene adopts a very clear theoretical methodology of forming binary opposites. His use of opposites, or opposition, is essential for the creation of a distinction between classical and hypermodern chess. Yet this position implies a conflict between the two styles of chess play that is not necessarily true. One of the intrinsic characteristics of Hypermodernism is its connectedness with the movement it surpassed.

The relationship does lie in the realms of Hypermodernism and Dada and yet it goes much further, as Duchamp goes further than Dada. Thus, Keene’s whole approach to find the solution to the problem of Duchampian chess is mistaken.

An interview between Ralph Rumney and Francois Le Lionnais was the catalyst for this thesis and investigation. I set out to determine which one of the theorists was correct, and it was not until I reconsidered my methodology that an alternative conclusion could be reached. Ralph Rumney has just asked Le Lionnais to describe Duchamp’s qualities as a player,

FRANCOIS LE LIONNAIS I don’t know how well I can do that . . . in his style of play I saw no trace of . . . a Dada or anarchist style though this is perfectly possible. To bring Dada ideas to chess one would have to be a chess genius rather than a Dada genius. In my opinion Nimzowitsch, a great chess player was a Dadaist before Dada. But he knew nothing of Dada. He introduced an anticonformism of apparently stupid ideas which won. For me that’s real Dada. I don’t see this Dada aspect in Duchamp’s style. . . .

RALPH RUMNEY You say he was not a Dadaist as a chess player. . . but was he an innovator?

FRANCOIS LE LIONNAIS Absolutely not. He applied absolutely classic principles, he was strong on theory – he’d studied chess theory in books. He was very conformist which is an excellent way of playing. In chess conformism is much better than anarchy unless you are Nimzowitsch, a genius.

This exchange ends with Rumney posing a question:

It seems to me that the extremely conformist style of Duchamp’s chess which you describe has parallels in everything he did, and that perhaps instead of looking for evidence of Dada in the way he played chess we should be looking for aspects of this conformism in his most anti-conformist action?

Le Lionnais, it would seem, contradicts Keene’s understanding of Duchamp’s chess. Instead of looking for conformity within Duchamp’s art, Keene refutes the very grounds for such an inquiry by stating that Duchamp was a Dadaist chess player and did not adopt a conformist or classical style. Yet even the investigation suggested by Rumney will bring us to a binary end. Lionnais claims to have seen no evidence of Duchamp’s Dadaist or hypermodernist chess play but instead a classical approach. Duchamp is either a conformist or a non- conformist artist, and Duchamp is either a conformist or non-conformist chess player. In the end this will not bring us to an understanding of Duchampian chess, but a series of binary oppositions. Keene reached this conclusion even though the original question was what sort of player was Duchamp? This investigation into Duchamp’s chess is met with two opposing views; he is either a Hypermodernist or a Classicist. The historian is being asked to determine whether Keene or Lionnais is correct.

The comparison between the chronological order of [my] paintings and a game of chess is absolutely right . . . But when will I administer checkmate – or will I be mated?

Click to Enlargefigure 3

Marcel Duchamp, The Green Box, 1934

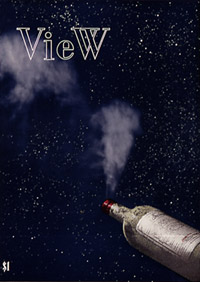

Duchamp dropped clues along his way as to how we are to understand chess. When Duchamp co-wrote a chess book on end-game with chess theorist Vitaly Halberstadt, he collected all of the notes that he made in preparation for the book’s publication and placed them all in a ‘box’. He titled this ‘box’ The box of 1932. What is significant about the act of Duchamp ‘boxing’ his proofs and diagrams, is that it identically reflects his act of ‘boxing’ all of the notes he made in preparation for his Large Glass. Duchamp titled this box The Green Box (Fig. 3), and used it to take the viewer into the world of the ‘bride’ and the ‘bachelors’ the two major aspects of the Large Glass. Thus the Box of 1932 is to L’Opposition et les cases conjuguees sont reconciliees as The Green Box is to the Large Glass. Duchamp did not make any indication that his theoretical work on chess was to be understood through the shattered glass of his Bride. It is through the multiple paradigms in which Duchamp was involved, that we are to understand and represent him as an historical figure. Duchamp as artist sharing the values of other paradigms and bringing what is seen as incommensurate into unity. Duchamp has offered an explanation as to how two apparently incommensurate elements are united through the concept of ‘inframince’ (Fig. 4). figure 4

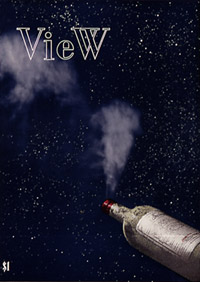

figure 4

Marcel Duchamp, front cover for View, vol. 5, no. 1 (March 1945)

WHEN

THE TABACCO SMOKE

SMELLS ALSO

OF THE MOUTH

THAT EXHALES IT THE TWO ODOURS

ARE MARRIED

INFRAMINCE.

The smell of smoke and the mouth are distinct and separate entities, though through the act of smoking, the two odors are combined forming a ‘new thought.’

Thus through inframince, art and chess are married in the life and work of Marcel Duchamp. The relationship between art and chess is very complex and multi layered, and is not able to be reduced to a meta theory or solved by dismissing Duchamp’s engagement with chess.

The many paradigms in which Duchamp ‘worked’ or ‘played’ need to be understood as blending within art, via this understanding of inframince, like that of the smoke mixing with another odor. This proposed historical methodology is not only relevant to Duchamp but to all historical figures. The various contradictory positions held by historians and theorists concerning Duchamp and his incommensurate activities can be understood by the history of art. Art is what is brought into existence via a series of established conventions and fulfils various criteria. Postmodernism offers a perspective that is able to bring together that which was an anomaly to modernist historical representation of Duchamp. It is through postmodernism that the ‘sub-systems’ that Duchamp was part of can be understood and can become part of his historical representations. Unity can be created through acknowledging the existence of these paradigms and the way in which Duchamp’s activities created ‘inframince’ with each other: art and chess, chess and art, chess and science, science and art. Duchamp is ‘found’ through an historical and theoretical methodology founded upon such postmodern multiplicity.

Chess and Art “reconciled”

It is important to make a connection between many of the theories of Nimzowitsch and that of Duchamp, in particular those of aesthetics and thought. Duchamp made many statements that his art was an intellectual activity and he was critical of what he termed ‘retinal’ art. This is similar to the criticism that the Hypermodern chess players had for the classical school: classical theories were based on (formalistic) aesthetics and not on the intellect or logic. Duchamp’s interest in the intellect went beyond the realms of chess and he wished for a similar intellectual direction to take place in art.

This is the direction in which art should turn: to an intellectual expression.

There is a mental end implied when you look at the formation of the pieces on the board. The transformation of the visual aspect to the gray matter is what always happens in chess and what should happen in art.

The observation that the words of Duchamp mirror those of Nimzowitsch have been made by a number of theorists. Some even go so far as to suggest that Duchamp’s Large Glass mirrors diagrams that Nimzowitsch used in his 1925 publication, which divided the chess board in two.

This is not to suggest that the way to understand Duchamp’s art is through his chess, but it is helpful to break down the intellectual barriers that exist between art and chess thus forming a reconciliation of these two paradigms in the person Duchamp.

Click to Enlargefigure 5

Marcel Duchmap, Opposition and Sister Squares are Reconciled, 1932In 1932, Duchamp, in collaboration with Vitaly Halberstadt, wrote a study on a specific end game situation titled L’Opposition et les cases conjuguees sont reconciliees (Opposition and Sister Squares Are Reconciled) (Fig. 5). Duchamp spoke of it as purely an intellectual study with no real practical application, for the situations being presented rarely came about.

He said to Cabanne,

The endgames on which this fact turns are of no interest to any chess player: and that’s the funniest thing about it. Only three or four people in the world are interested in it, and they’re the ones who’ve tried the same lines of research as Halberstadt and myself. Since we wrote the book together, chess champions never read this book, because the problem it poses never really turns up more than once in a lifetime. These are possible endgame problems, but they’re so rare that they’re almost utopian.

Duchamp called his work a “linguistic study,” which Damisch claims the Duchamp / Halberstadt text is built around the notion of ‘opposition.’

Using the language from a number of paradigms, especially from aesthetics and philosophy, to explain scientific and mathematical foundations of his chess theories.

Duchamp’s and Halberstadt’s discussion in L’Opposition et les cases conjuguees sont reconciliees involve end-game problem, and their discussions are very much couched in geometrical language, involving ‘translation,’ ‘displacement,’ and ‘rotation’ around ‘charniere’ or ‘hinges.’ Charniere’ is the term that Duchamp used in his mathematical notes to mean an ‘axis o rotation.’

Saussure directly uses the model of chess to introduce his oppositional theories of language. Damisch quotes from a small section where Saussure explains that it is only through words opposing one another that meaning is created;

a given term having . . . no value except through difference and through its opposition to the other terms in the language.

And furthermore that the relationship between languages and chess is,

Just as the game of chess is entirely in the combination of the different chess pieces, language is characterized as a system based entirely on the opposition of its concrete units.

Click to EnlargeFigure 6

Marcel Duchamp, Trébuchet, 1917/1964The end game is fundamentally a stage of opposition, where the only pieces that remain are the two Kings and some pawns.

Opposition is defined during the end game when symmetry is presented by the position of the Kings and pawns. The aspect of the end game that Duchamp and Halberstadt were concerned about was when a symmetry or a formalist structure arise and each player is struggling to keep equilibrium for survival. For there is security in symmetry during such situations because a player is able to restrict or control the moves available to the opponent. At the same time, due to the symmetry, a player may be forced into making a move that will cause their own defeat, otherwise known as a Trap or Trebuchet (the title of his 1917 Readymade) (Fig. 6). In opposition there is a paradoxical element that interested both Duchamp and Nimzowitsch. Duchamp and Halberstadt’s book attempted to reconcile the two components of symmetrical endgame situations; opposition and sister squares. The squares represent the squares on the chess board that remain relevant to the chess pieces in symmetry. Hence the title of Duchamp’s book Opposition and Sister Squares Are Reconciled. The way that Duchamp explained it is as such,

The “opposition” is a system that allows you to do such – and – such a thing. The “sister squares” are the same thing as opposition, but it’s a more recent invention, which was given a different name. Naturally, the defenders of the old system were always wrangling with the defenders of the new one. I added “reconciled” because I had found a system that did away with antithesis.

It is important to notice that within Duchamp’s study of endgames there is not an attempt to create further opposition by Duchamp positioning himself with one side or the other. Duchamp separates himself from the debates between the Classical school or “old system” and the hypermoderns. He was able to see that with hypermodernism there was an opportunity to create a synthesis between these two opposing understandings of end game theory. In so doing he displays a typically Hypermodern paradoxical attitude to classical theory.

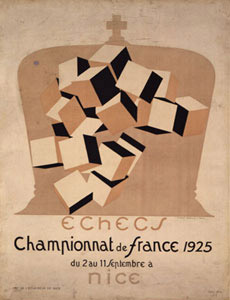

Click to EnlargeFigure 7

Marcel Duchamp, Poster for the Third French Chess Championship, 1925 Rhonda Roland Shearer CollectionLet us take this one step further towards Duchamp ‘reconciling’ art and chess. Damisch makes the point that Duchamp’s chess poster designed for the 1925 Third French Chess Championship (Fig. 7) mirrored his theory of reconciliation. Duchamp extended the checkers of the chess board until they became cubes with one white, black and a third grey side, grey being the side of reconciliation. In the game of chess it is the opposition between black and white that gives the game its meaning. However, the ‘binary’ opposition of chess is defeated by Duchamp in the presence of the grey surfaces.

Let us return to Naumann’s article and interview contained in De Duve’s The definitively unfinished Marcel Duchamp. Francis Naumann presents Duchamp’s involvement in philosophical ‘reconciliation’ in the context of the German philosopher Stirner and the philosophical beliefs of existentialism and nihilism: That each position or situation exists as a unique entity, thus unable to be located within specific systematic constraints. Naumann points out that reconciliation is not only found in the works of Stirner but has a philosophical tradition that goes back to Plato.

More than that, ‘reconciliation’ is present in contemporary theories of structuralist theory, molecular biology, metaphysical poetry, and French symbolist poets. Thus this theme of ‘reconciliation of opposites’ is present in a number of intellectual domains. The theme is similarly reflected in writings since medieval times up until the time of Carl Jung who specifically wrote on the subject in Mysterium Coniunctionis: An Inquiry into the Separation and Synthesis of Psychic Opposites in Alchemy.

Yet Naumann warns us that one must be careful in the creation of a theory about Duchamp, for he consciously set out never to repeat himself and thus be defined. Naumann says:

No matter what his sources may have been – if any – his exploration of opposites and their reconciliation seems to have been motivated more by his unwillingness to repeat himself than by any possible willingness to conform to the dictates of a previously established system – philosophical, literary – or otherwise. His working method involved a constant search for

alternatives – alternatives not only to accepted artistic practice, but also to his own earlier work.

Naumann states that Duchamp was familiar with many aspects of reconciliation in maths, science, linguistics and philosophy. Therefore the relationship between chess and art in the historical figure Duchamp is contained within a wide intellectual field.

Historian Calvin Tomkins makes the similar observation that Duchamp’s fascination with art and chess seems to be bound up in mathematics.

The importance of logic, rationalism and Cartesian thought are an integral part of Duchamp’s work coupled with an anti-rationalistic interest, as seen in the works of Raymond Roussel and Alfred Jarry. Also Duchamp’s use of the term Cartesian is implicit of Descartes idea of man as a thinking mind, and matter an extension of motion. In terms of chess this duality is clearly seen, the movements of chess pieces upon a board are the physical expression of the chess player’s cognition. In an interview with Tomkins, Duchamp says:

Chess is a marvelous piece of Cartesianism, and so imaginative that it doesn’t even look Cartesian at first. The beautiful combinations that chess players invent – you don’t see them coming, but afterward there is no mystery – it’s a pure logical conclusion.

When the life and actions of Duchamp are placed within the historical context of Postmodernity we find the merger or reconciliation of a variety of intellectual paradigms. Duchamp’s studies into chess drew upon the knowledge and language of science, mathematics, and linguistics. Thus in order to understand the life and actions of Marcel Duchamp we must strive to understand the nature of intellectual reconciliation.

Duchamp as Chess Artist

And why . . . isn’t my chess playing an art activity? A chess game is very plastic. You construct it. It’s mechanical sculpture and with chess one creates beautiful problems and that beauty is made with the head and hands.

“I play chess all the time,” he wrote to Walter Arensberg. “I have joined the club here where there are very strong players classed in categories. I still have not had the honor of being classified, and I play with various players of the second and third categories losing and winning from time to time.” He had a set of rubber stamps made up so that he could play correspondence chess with Walter Arensberg. He even designed a set of wooden chessmen that he carved himself, all except the knight, which he farmed out to a local craftsman. In May he wrote to the Stettheimers that painting interested him less and less: “I play [chess] day and night and nothing interests me more than to find the right move..

It is deep below the layers of chess symbolism that Duchamp is encountered as a chess player and an artist. Art theorist Hubert Damisch raised the question as to why we encounter Duchamp in the world of chess at all. Damisch asks: how could he have spent so much of his life involved in nothing but a game? He makes a point of comparison, that Duchamp spent more of his life within this realm than he spent painting, though Duchamp renounced “neither the notion of “artist” nor that of “art.”

How has Duchamp slipped so easily into the realm of chess and become so difficult to follow? I have suggested that it is the art world’s scorn and misunderstanding for the game. Yet it is not within the “game” that we encounter Duchamp. The artist moved into the world of chess and it is here that the art theorist and historian loses Duchamp. What is significant is that Duchamp was able to enter the world of chess only due to his entering as an artist. Duchamp understood chess via the language, values, history, and culture of art. Thus on entering the world of chess we need to find the artist Duchamp. He was not found in the realm of symbolism, though he has left his footprints there, to perhaps lead us astray. When Duchamp entered the chess world he entered as an artist and he proclaimed that art was to be found here. Damisch summarizes Duchamp’s interest for chess as an artistic activity, and that a game of chess is considered “beautiful” in its own right and is as close as possible to becoming a work of art.

Damisch understands Duchamp’s involvement in chess as deeply connected with his agenda as an artist. Damisch asserts that he was not interested in the symbolism of the chess pieces, the layers of historical meaning, or the psycho-sexual elements, but the way that chess was able to evoke abstract and intellectual movement of objects upon a new space or reality. This point Duchamp directly made when he answered the specific question as to the importance of symbolism in chess. Duchamp said that it holds no importance in the game, although chess acts like a drug of addiction.

Duchamp later said that the “expression” of chess and the “competitive” nature made it too incongruent with art, and thus is no art form at all. However, for Duchamp, it was not important to understand chess as a fight, or “sport” but through artistic qualities. This he explicitly stated during a BBC radio interview, when saying that the “competitive aspect was of no importance.”

Of course, one intriguing aspect of the game that does imply artistic connotations is the actual geometric patterns and variations of the actual set up of the pieces and in the combinative, tactical, strategical, and positional sense. It’s a sad expression though – somewhat like religious art – it is not very gay.

Here Duchamp is presenting three ‘artistic’ or aesthetic levels concerning the game. First, the immediate visual impression of the chess pieces upon the board. This includes the chequered board, the sculptural formation of the pieces, and the variety of visual patterns that they form upon the board. Second, the abstract movement of the pieces through the ‘intellectual’ space. Finally, the emotional expression of chess.

The first level of aesthetics were explored by Duchamp in designing (but never making) a chess set. Writing to his sister Suzanne Duchamp he explained,

I am about to launch on the market a new form of chess sets, the main features of which are as follow: The Queen is a combination of a Rook and of a Bishop – the Knight is the same as the one I had in South America. So is the Pawn. The King Too. 2nd they will be colored like this. The white Queen will be light green. The black Queen will be dark green. The Rooks will be blue, light and dark. The bishops will be yellow, light and dark. The knights, red, light and dark. The white King and Black King. White and Black Pawns. Please notice that the Queens’ colour is a combination of the Bishop and of the Rook (just as she is in her movements).

While the immediate visual impression of the chess set would be striking, its purpose is to direct our attention to the second aesthetic level; the intellectual movement of the pieces. This is directly indicated by the coloring of the Queen – its movement being a combination of a Bishop and a Rook. His engagement in chess is seen as profoundly relating to the intellectualized movement of the pieces, to which he has brought the inventiveness of an artist to the aesthetics of the game. It is the ‘artistic’ intellectual and abstract movement of pieces that Duchamp, the artist, values within chess.

Duchamp spoke most openly and comprehensively to Pierre Cabanne concerning this perspective on the game. This interview sheds light upon a vast array of Duchamp’s chess quotations and references commonly used by historians and theorists when speaking on the subject.

Cabanne: I also noted that this passion [for chess] was especially great when you weren’t painting. So, I wondered whether, during those periods, the gestures directing the movements of pawns in space didn’t give rise to imaginary creations – yes, I know, you don’t like that word – creations which, in your eyes, had as much value as the real creation of your pictures and, further, established a new plastic function in space.

Duchamp: In a certain sense, yes. A game of chess is a visual and plastic thing, and if it isn’t geometric in the static sense of the word, it is mechanical, since it moves; it’s a drawing, it’s a mechanical reality. The pieces aren’t pretty in themselves, any more than is the form of the game, but what is pretty – if the word ‘pretty’ can be used – is the movement. Well, it is mechanical, the way, for example, a Calder is mechanical. In chess there are some extremely beautiful things in the domain of movement, but not in the visual domain. It’s the imagining of the movement or of the gesture that makes the beauty, in this case. It’s completely in one’s grey matter.

Cabanne: In short, there is in chess a gratuitous play of forms, as opposed to the play of functional forms on the canvas.

Duchamp: Yes. Completely. Although chess play is not so gratuitous; there is choice ..

Cabanne: But no intended purpose?

Duchamp: No. There is no special purpose. That above all is important.

Cabanne: Chess is the ideal work of art?

Duchamp: That could be. Also, the milieu of chess players is far more sympathetic than that of artists. These people are completely cloudy, completely blind, wearing blinkers. Madmen of a certain quality, the way the artist is supposed to be, and isn’t, in general. That’s probably what interested me the most.

Cabanne poses a range of questions directly concerning the relationship between art and chess. Cabanne begins by establishing an opposition to, or a clear distinction between, chess and art. The term Cabanne actually uses is “painting” yet in its context the word “art” is clearly implicit. The question posed to Duchamp points directly to the relationship Cabanne saw existing between chess and art. Cabanne asked Duchamp when he was not in the paradigm of art whether the movements of chess pieces gave rise to anything that he would value as art; and whether Duchamp discovered a new realm or space for art within chess. In affirmation of this, Duchamp continues to present an explanation of this artistic encounter within chess. As in his chess set design, Duchamp draws our attention to the multiple levels operating within the aesthetics of chess, and directs us to the aspect which he holds in the highest regard. Duchamp’s interest in the movements of a machine, a mystical machine, as directly and simply illustrated in his 1911 Coffee Grinder, operate also in the realm of chess, where the movements of the grinding mechanism is visible and the process or movement of the coffee through the machine is demonstrated. This is shown most clearly in Duchamp’s body of work that make up the King and Queen. There is a clear focus upon the movement of pieces upon the board in intellectual space.

Developing this further, Duchamp reflects on the close relationship chess has to geometry and mechanical movement. The example he presents is the movement of Calder’s mobiles. But a mobile is aesthetic in the realm of the visual and Duchamp says that the aesthetics of chess are not in this domain. It is not even the physical sculptural pieces that are aesthetic or “pretty” – it is the movement of the pieces in intellectual space. The beauty of chess that Duchamp saw was the movement of the pieces within his mind. This is testament to what Duchamp said to Drot,

|

And further,

|

Mechanics in the sense that the pieces move, interact, destroy each other, they’re in constant motion and that’s what attracts me. Chess figures placed in a passive position have no visual or aesthetic appeal. It’s the possible movements that can be played from that position that makes it more or less beautiful.

Actually when you play a game of chess it is like designing something or constructing a mechanism of some kind by which you win or lose. The competitive side of it has no importance, but the thing itself is very, very plastic and it is probably what attracted me to the game.

|

Cabanne presents Duchamp with a summary of this understanding: The distinction between the aesthetics of chess and art (painting) is that in chess there is a free movement or “play of forms” whereas in art, forms are not considered to be free for they serve a functionally aesthetic purpose. Cabanne has made the battle ground for this debate the issue of values associated with aesthetic functionality. Duchamp corrects Cabanne by saying that the aesthetics of chess are concerned with the “play of forms” in intellectual space, however, the movement is restricted by choice, and each choice brings its own consequences just as the artist also faces the consequences of their actions. Chess is not free or “gratuitous” as crudely expressed by Cabanne.

Duchamp and David Antin wrote an article (in response to an interview they had conducted) in which they illustrate the choice and consequences within the intellectual realm of chess and the weight of meaning and significance placed upon a small sculptural object, the chess piece.

but I don’t want to talk about that now I would rather talk about chess since we’re talking about Duchamp its only right that we should talk about chess chessboards define the action in chess the action is usually on the board similarly if you use the word art you use a board as a perimeter and some where within the perimeter is the site of a action at least it would appear so to someone who knew how to play chess which is an action of a different sort for someone know how to play chess for if two people two chess masters are playing a game and somebody watches that game and he gasps ostensibly this is an act of little significance a man pushes a little piece of wood and moves it over here say and the other man gasps he watches the man next to him doesn’t know why he’s gasping the first man is gasping because the player whose move it was has just moved the bishop to a particular position on the board from which will ensure 15 alternative possibilities all of which are not very good.

This interest in intellectual movement was also Duchamp’s concern within painting, ‘intellectual expression’ was the direction that painting should take. Duchamp said;

I considered painting as . . . a means of expression, instead of a complete aim for life . . . the same as I considered that colour is only a means of expression in painting. It should not be the last aim of painting. In other words, painting should not be only retinal or visual; it should have to do with the gray matter of our understanding, not only the purely visual.

American Chess Master Edward Lasker saw that Duchamp’s interest in the aesthetics of chess had profound effects on Duchamp the chess player. Duchamp’s aesthetic concerns and insights influenced his style of play which had immediate implications on many of his tournament results. Duchamp was ever the artist within the world of chess. Schwarz also acknowledges that Duchamp’s aesthetic interest in chess, coupled with his “unorthodox” style led to many defeats at chess master levels.

Duchamp’s interest in chess also revolves around the contradiction or paradox that exists between freedom and restriction. Within a strict framework of rules, there is great room for creative and imaginative thought. Duchamp’s Cartesian sentiments, also presented insights into the aesthetic realm of chess.

Chess is a marvelous piece of Cartesianism, and so imaginative that it doesn’t even look Cartesian at first. The beautiful combinations that chess players invent – you don’t see them coming, but afterward there is no mystery – it’s a pure logical conclusion.

Duchamp’s Hypermodernist chess praxis questioned all previously established styles and theoretical principals whilst maintaining a rigorous mathematical and scientific methodology. Duchamp as a chess player closely associated himself with Hypermodernism not only for its Dadaist position but also for its rigorous mathematical and logical approach. It was through a Cartesian approach that Duchamp wrote Opposition and Sister Squares Are Reconciled with chess theorist Halberstadt. This text has been observed to involve the “seemingly aimless maneuvers of the kings,” yet it shows his interest in the mathematic logic of chess.

His intellectual interest in both the acceptance and rejection of logical thought, or of freedom and restriction, became an interest in the middle ground. A middle ground of indifference, which he considered the “beauty of indifference,” and “an acceptance of all doubts.”

This “indifference” reflects Duchamp’s adoption of a Hypermodern chess style which is an interplay of romantic and modern forms. He explained his attitude of indifference to Andre Breton:

For me there is something else in addition to yes, no or indifferent – that is, for instance – the absence of investigations of that type. . . . I am against the word ‘anti’ because it’s a bit like atheist, as compared to believer. And the atheist is just as much of a religious man as the believer is, and an anti-artist is just as much of an artist as the other artist. Anartist would be much better, if I could change it, instead of anti-artist. Anartist, meaning no artist at all. That would be my conception. I don’t mind being an anartist . . . What I have in mind is that art may be bad, good or indifferent, but, whatever adjective is used, we must call it art, and bad art is still art in the same way as a bad emotion is still an emotion.

Duchamp was reluctant to draw a distinction between the artist and the anti-artist, which questions whether a theorist should make the distinction between art and chess. An indifference to the division between art and chess creating a free flow of ideas between the two. This free flow or traversal of paradigms existed not only between chess and art. Duchamp’s interest in this intellectual paradox flowed into his involvement in mathematics. Henri Poincare is believed to have presented Duchamp with a position that emphasized the resolution of the paradox. Poincare’s mathematical text Science et method has a chapter concerning mathematical invention, which suggests that by using the laws of mathematics one is able to be as inventive, imaginative and creative as a chess player. Poincare says that all mathematicians have “a very sure memory” or,

a power . . . like that of the chess player who can visualize a great number of combinations and hold them in his memory, . . . every good mathematician ought to be a good chess player, and inversely.

Poincare understood chess to be fundamentally associated with invention. An invention of pure elements of “harmony of number, and forms, of geometrical elegance.”

That strict rules and laws exists both within mathematics and chess. Within this framework, the practitioner is able to move and act freely and inventively. It has been suggested that chess operated for Duchamp as an arena of invention that he occupied after completing his conceptual and mathematical invention, the Large Glass.

Julien Levy said of Duchamp:

Marcel wanted to show that an artist’s mind, if it wasn’t corrupted by money or success, could equal the best in any field. He thought that, with its sensitivity to images and sensations, the artist’s mind could do as well as the scientific mind with its mathematical memory. He came damn close, too. But, of course, the memory boys were tougher, they had trained [for chess] from an early age. Marcel started too late in life.

Duchamp was seen by many of his chess opponents to be highly creative, and his use of inventive or “playful” mathematics within the Large Glass, demonstrates Duchamp’s freedom of movement between these paradigms. And perhaps it is within this context that we are to understand Duchamp’s statement that

From my close contact with artists and chess players, I have come to the personal conclusion that while all artists are not chess players, all chess players are artists.

Duchamp came to conduct chess as an artist and to conduct his art making as the chess player.

The theorist David Joselit also explores the way that chess and art relate in Marcel Duchamp’s life and art. Joselit sees chess as “living art” within Duchamp’s life. In which there is a traversal between art and chess as there is Duchamp’s traversal between art to life.

He took an ordinary article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view – created a new thought for that object.

Click to EnlargeFigure 8

Original Studio Photograph, 1916-17The photograph of Duchamp’s studio from 1917 presents the framework for this theory. Hanging vertically upon a wall is chess as a physical object, as opposed to the intellectual realms of chess, and upon the floor, chess as a conceptual reality via the readymade sculpture the Trap (Fig.8). It is well known that Duchamp played correspondence chess and these vertical boards were commonly used to illustrate his games in progress. The depth of logical methodology saw Duchamp thrive in correspondence chess and endgame studies. In these instances, the slow pace of the game creates little scope for oversights and incorrect moves, thus a purer logic is achieved. Joselit views this vertical chessboard through art stating that it has entered the arena of the painting. The chess board has entered or ‘colonized’ the paradigm of art via painting.

The rotated chess board suggests that the relationship between chess and art was not necessarily one of displacement but rather of the transformation or transposition of painterly themes into a realm that obviates “the intervention of the hand.”

The flat vertical image upon a wall, yet the physical transient reality of chess, becomes an “erasable beauty” a painting that can be erased and begun over and over again.

Likewise Duchamp said:

At the end of the game you can cancel the painting you are making.

Duchamp wrote the following note that further expresses this:

Chess = a design on slate / that one erases, / the beauty of which / one can reproduce without the / intervention of the “hand.”

Click to EnlargeFigure 9

Marcel Duchamp, Coffee Mill, 1911 Thus Duchamp saw chess enlightening the paradigm of art. Chess is an “aesthetic idiom” to mathematically represent an “immobilized” movement as is seen in the Large Glass (1923) (Fig. 2) and Coffee Mill (1911) (Fig. 9). The artist chess player is able to “diagram it, to capture it within a grid of measurement.”

Joselit’s hypothesis is that chess is a projection into Duchamp’s world of the readymade as clearly displayed in the studio photograph. The readymade represents Duchamp’s traversal between art and everyday life and chess. Trebuchet or Trap draws directly from a theoretical movement within chess. This readymade sculpture is created by Duchamp by nailing a coat rack down upon his studio floor. Trebuchet is a tactical chess move that incites a player to make a move that will ultimately cause them to lose a positional advantage, a piece, or the game. The analogy of being tripped by the inverted coat rack is obvious, one Duchamp actually encountered when he brought the object home and never got around to mounting it to the wall. Duchamp becomes the chess piece tripped by the Trebuchet that was set by himself. Joselit sees a direct connection between the chess board tipped upon a wall and the coat rack that has been tipped down upon the floor. Each work has entered a new realm via its displacement. Duchamp the chess player in the realm of art and Duchamp the artist in the realm of chess, both in the realm of the everyday. Joselit understands that within this photograph, chess operates as a pivot for understanding the movement from the realm of painting to the realm of Duchamp’s readymades. Joselit says that these two works demonstrate the “discursive field that we might call ‘Duchampian chess.'”

To understand what is occurring within Duchamp’s art we need to understand the way chess operates as a theoretical and practical model. Within chess Duchamp enters the arena of the painting via the chess board hung upon a wall. The physical chess object can be aestheticised like that of a painting. Duchamp also enters the realm of the readymade object in his studio and the conceptual movement of correspondence chess through intellectual space via an arena of readymade rules and intellectual visualization. Through documentation and notation Duchamp geometrically charted the movement of the readymade upon the painterly plane. Then the entire chess object is placed within the context of the everyday. It is this nature of the everyday that prompted Duchamp in 1917 to publish a game of chess between the artists (both poor chess players) Roche and Picabia, in a regular chess column of a news paper. The readers were outraged! Duchamp wrote in response to this Richard Mutt Case of the chess world that;

It had been a game from everyday life: lyrical, heroic, romantic; with blunders, sudden panic reactions, flights of imagination and here and there even a correct move.

Joselit believes that Duchamp aimed to invent an art form that was equally as elegant and conceptually beautiful as chess and cites chess as being responsible for Duchamp’s low artistic production during the 1920’s. Joselit writes,

The game was no mere idle pastime for the artist, a smoke screen that could block the scrutiny of the art world. Rather, . . . chess, like the machine before it, provided Duchamp with a productive conceptual and aesthetic model that was unquietly capable of synthesizing the “spatial realism” or literalness of the readymade and the systemic complexity of the Large Glass.

The systemic complexity concerning the Large Glass operates in a similar way to the game of chess. In this work, Duchamp established a conceptual mechanism which is understood to operate via the rules and laws referenced in the Green Box. The way to understand the workings of the Large Glass is via the Green Box. For example Duchamp’s use of colour must be understood via the associated notes. Duchamp wrote, “As in geographical maps, as in architects’ drawings; or diagrams with colour wash, need a colour key: substantive meaning of each colour used.”

Likewise, for chess, the conceptual workings and movements of the pieces operate via the established readymade rules of the game.

This comparison between the workings of the Large Glass and chess was also noted by Linda Dalrymple Henderson in her 1983 text entitled The Fourth Dimension and Non-Euclidean Geometry in Modern Art. She claims we see in the works of Duchamp a similarity of approach to chess and art, through the ‘geometrical theorizing’ in chess and in the notes for the Large Glass.

Duchamp believed that language united his life with the Large Glass and with chess. Yet he maintained the belief that language was unable to communicate purely:

I don’t believe in language, which, instead of explaining subconscious thoughts, in reality creates thought by and after the word . . .

Duchamp was able to maintain the purity of the Large Glass by adopting and inventing a language of paradoxical referencing and operation, like the specialized chess.

Likewise the world of the Large Glass does not operate beyond its glass surface.

Duchamp was able to create a theoretical union whilst acknowledging the incommensurability of chess and art. A methodology that is not associated with hierarchy or dominance or comparison of criteria, but an approach that enters into the distinct paradigms of art and chess themselves. Marcel Duchamp enters chess holding onto the values of art: Not claiming that chess is art but valuing chess as he values art.

Notes

1. Bois, Hollier & Krauss, A conversation with Hubert Damisch, October #85 Summer, 1998, p.10.

2. Damisch, Hubert, The Duchamp Defense, 1979, October # 10, p.8

3. Hughes, Robert, Shock of the New, Thames & Hudson, London, 1991, p.52.

4. Damisch points out that Duchamp was interested in chess as a young man as shown by an etching by Jacques Villon (Marcel’s brother) showing Marcel playing chess with his sister at the age of seventeen. Duchamp played in the 1924 World Amateur Championship, four French championships from 1924 to 1928, and four Olympiads from 1928 to 1933. He tied for first place at Hyeres 1928 and won the Paris championship in 1932. He drew a game with Grand Master Tartakower in 1928. Several times he beat Belgian Champion Koltanowsky in 1929. He was awarded the chess title of Master in 1929. In 1931 Duchamp became a member of the Committee of French Chess Federation and the French delegate to the World Chess Federation. In 1931 Duchamp co-wrote a book on chess with Halberstadt titled L’Opposition et les cases conjures sont reconciliees. In 1935 Duchamp was Captain of the French Correspondence Olympic team.

5. Damisch, Hubert, The Duchamp Defense, 1979, October # 10, p.8. It is important not to read painting to mean art. Although Duchamp ceased painting his career as an artist continued.

6. Damisch, p.8.

7. Ibid, p.5-9.

8. Tomkins, Calvin, Ahead of the Game, Marmondsworth, Middlesex, Penguin, 1965, p.52-3.

9. Humble, Marcel Duchamp: Chess Aesthete and Anartist Unreconciled, Journal of Aesthetic Education, Vol.32 no.2, 1998, p.41.

10. Naumann, Francis, “Marcel Duchamp: A Reconciliation of Opposites,” de Duve, Thierry, ed., The Definitively Unfinished Marcel Duchamp. Cambridge, MIT Press (co-published with Nova Scotia School of art and Design). 1993, p.41.

11. Ibid, p.41.

12. ‘A Conversation with Marcel Duchamp’. A 30 minute film directed by Robert Graff incorporating an interview by James Sweeney, made at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1955 and broadcast by NBC in January 1956 in the program Elderly Wise Men.

13. Raymond Keene, Marcel Duchamp: The Chess Mind, Modern Painters, vol.2, no. 4, winter 1989, p.121

14. Rumney, R. “Marcel Duchamp as a Chess Player and One or Two Related Matters: Francois le Lionnais Interviewed by Ralph Rumney” Studio International 189 no.972 (January-February), 1975, p.127

15. Keene, p.123

16. Rumney 1975, p.128

17. Jones, A. Postmodernism and the Engendering of Marcel Duchamp. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1994, p. 120.

18. View, ser. no.1, March 1945.

19. Duchamp (R.Mutt), The Blind Man, New York, 1917, found in Harrison/Wood, Art in Theory 1900 – 1990, Blackwell, 1992, p.248.

20. Sweeney, J. A Conversation with Marcel Duchamp, Wisdom: Conversation with the Elder Wise Men of Our Day, New York, W.W. Norton & Co., 1958, p.94-5.

21. Quoted in Damisch, Hubert, The Duchamp Defense, 1979, October # 10, p.10

22. Masheck, J., Marcel Duchamp in Perspective, New Jersey, Prentice-Hall, 1975, p.19.

23. Damisch, p.19-21.

24. Cabanne, Pierre, P. Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp. New York, Viking Press, 1971, p.77-8.

25. Damisch, p.22.

26. Adcock, Craig, Marcel Duchamp’s Notes for the Large Glass: An N-Dimensional Analysis, Ann Arbor, p.63.

27. Damisch, p.14. Quoting Ferdinand de Saussure, Course in General Linguistics, eds. Charles Bally and Albert Sechechaye, trans. Wade Baskin, New York McGraw-Hill, p.107.

28. Ibid, p.14

29. This work is concerned with that very special point of the endgame in chess when all the pieces have been lost, only the Kings and a few pawns remain on the board. And this special ‘lone-pawns’ situation is treated only from the even more particular situation in which the pawns have been blocked and only the Kings can play. This situation is called zugzwang, a German term of international use that indicates this blocked position in which only certain moves, and in a limited number, are possible. In this case (pawns blocked and only the Kings being able to move), even though they make use of conclusions already established by Abbe Durand, Drtina, Bianchette, etc., Duchamp and Halberstadt are the first to have noticed the synchronisation of the moves of the black King and the white King. This synchronisation is analysed at length and forms the basis of their system. In order to win, a white King cannot move indiscriminately without regard for the colour of the square on which he finds himself. Using the terminology of the authors of the book, he must choose a ‘heterodox opposition’ with respect to the colour of the square occupied by the black King. This ‘heterodox opposition,’ which represents the real contribution of Duchamp and Halberstadt to the theory of chess, would demand a technical explanation too lengthy to be given here. At any rate, for clarity I would add that the game of chess does contain the idea of ‘opposition,’ and that Duchamp and Halberstadt have renamed it ‘orthodox opposition’ in order to distinguish it form the ‘heterodox opposition’ that they have discovered. This ‘orthodox opposition’ is something that all chess players know about, and it is far form being a mystery. It is a sure means of winning in certain situations. In fact, ‘heterodox opposition’ is no more than an amplification of opposition. It is simply applied to a longer number of squares, and it adopts various forms that are missing in the rigid ‘orthodox opposition.

30. Trap or Le Trebuchet is a technical chess term, and is also the subject of a readymade by Duchamp.

31. Damisch, p.24.

32. Ibid, p.25-6.

33. de Duve, p.55.

34. Ibid, p.53-7.

35. Ibid, p.57.

35. Ibid, p.57.

36. Tomkins, Calvin, Duchamp: A Biography. London, Random House, 1998, p.211.

37. Ibid, p.211.

38. Marcel Duchamp, interview by Truman Capote in Richard Avedon, Observation, NY: Simon and Schuster, 1959, p.55.

39. Tomkins 1998, p.210-11.

40. Damisch 1979, p.8.

41. Ibid, p.9.

42. Documentary film by Drot, J. M. A game of chess with Marcel Duchamp, L’institut National de’Audiovisuael Direction des Archives: RM Associates/Public Media, 1987.

43. Kremer, M. The Chess Career of Marcel Duchamp. New in Chess, Alkmaar, Holland, 1989, p.34

44. Duchamp quoted by Brandy, Schwarz, Marcel Duchamp. New York, Harry N. Abrams, Incorporated, 1975, p.70.

45. Duchamp quoted by Naumann, Affectueusement, Marcel: ten Letters from Marcel Duchamp to Suzanne Duchamp and Jean Crotti. Archives of American Art Journal, 22, No. 4 1982, p.14.

46. Cabanne, 1971, p.18-19.

47. Drot, J. M., 1987.

48. Duchamp, Salt Seller: the Writings of Marcel Duchamp, New York, Oxford University Press, 1973, p.136

49. D’Harnoncourt & McShine ed. Marcel Duchamp, MoMA, Prestel, 1989 p.100 (original published format has been maintained)

50. Schwarz, Arturo, The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp. London, Thames and Hudson, 1969, p.20.

51. Ibid, p.66.

52. Marcel Duchamp interview with Calvin Tomkins, undated, Tomkins, 1998, p.211.

53. Kremer, p.50.

54. Hamilton and Hamilton, BBC interview, London, 1959.

55. Duchamp quoted by Schwarz 1969, p.33.

56. Poincare, Science et methode, cited in Henderson, Duchamp in Context, Princeton, New Jersey, Princton University Press, 1998, p.186.

57. Ibid

58. Ibid

59. Schwarz 1969,p.70.

60. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. papers, August 30, 1952.

61. Duchamp, 1917, p.248.

62. Joselit, D., Infinite Regress: Marcel Duchamp 1910-1941. Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England, October, 1998, p.158

63. Joselit, D., Infinite Regress: Marcel Duchamp 1910-1941. Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England, October, 1998, p.160.

64. J. J. Tharrats, “Marcel Duchamp,” Art Actuel (Lausanne) 6 (1958): p.1

65. Marcel Duchamp, Notes, ed Paul Matisse, Boston: G.K.Hall, 1983, note 273, unpaginated.

66. Joselit, 1998, p.163.

67. Kremer, 1989, p.47.

68. Joselit, 1998, p.164.

69. Schwarz, 1969, p.27.

70. Joselit, 1998, p.173-4.

71. Henderson, Linda D., The Fourth Dimension and Non-Euclidian Geometry in Modern Art. Princeton, N.J., Princeton University Press, 1983, p.124.

72. Jones, p.133.

* The language of chess must be understood to go beyond the cliche of chess that are used in everyday speak like “checkmate” to the abstract world of piece movement, engagement, exchange, and combination.

73. M.D to Jehan Mayoux, March 8, 1956, Archives of Alexina Duchamp, Tomkins, 1998, p.394.

Fig.1-6, 8-9 © 2007 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP,

Paris.

1. Toujours inédits, les entretiens avec la famille Janis (Sidney, le père, Harriet, la mère, et Carroll, le fils) ont été faits à l’occasion de la préparation, par Duchamp, du catalogue et de l’accrochage de l’exposition Dada 1916-1923 à la Sidney Janis Gallery, New York, 15 avril-9 mai 1953. Dans la chronologie intégrée du catalogue Joseph Cornell / Marcel Duchamp… in resonance Joseph Cornell / Marcel Duchamp… in resonance, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 8 octobre 1998-3 janvier 1999, et The Menil Collection, Houston, 22 janvier-16 mai 1999, Ostfildern-Ruit, Cantz Verlag, 1998, p. 277, Susan Davidson, sans dire d’où elle tire cette précision, retient également le mois de décembre.

1. Toujours inédits, les entretiens avec la famille Janis (Sidney, le père, Harriet, la mère, et Carroll, le fils) ont été faits à l’occasion de la préparation, par Duchamp, du catalogue et de l’accrochage de l’exposition Dada 1916-1923 à la Sidney Janis Gallery, New York, 15 avril-9 mai 1953. Dans la chronologie intégrée du catalogue Joseph Cornell / Marcel Duchamp… in resonance Joseph Cornell / Marcel Duchamp… in resonance, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 8 octobre 1998-3 janvier 1999, et The Menil Collection, Houston, 22 janvier-16 mai 1999, Ostfildern-Ruit, Cantz Verlag, 1998, p. 277, Susan Davidson, sans dire d’où elle tire cette précision, retient également le mois de décembre. 2. Pierre Cabanne, Entretiens avec Marcel Duchamp, Paris, Belfond, 1967, p. 114.

2. Pierre Cabanne, Entretiens avec Marcel Duchamp, Paris, Belfond, 1967, p. 114. 3. C’est un jour après la rencontre d’André Breton, invité là, et douze jours avant que, le 17 janvier, Tristan Tzara n’arrive là pour y habiter, ce séjour coïncidant avec le début de ce que Michel Sanouillet a appelé “Dada à Paris”: voir sa somme, Dada à Paris, Paris, Pauvert, 1965. Le siège du “MoUvEmEnT DADA, Berlin, Genève, Madrid, New York, Zurich”, dit le papier à lettre qui arbore cet en-tête, est maintenant à Paris. Par ailleurs, je note la coïncidence (qui n’en était peut-être pas une en 1919, étant donné l’état des connaissances sur l’oeuvre de Léonard): lorsque Duchamp est à Paris cette année-là, les deux femmes (l’épouse et la maîtresse) de Picabia sont enceintes de garçons; lorsque Francesco del Giocondo, au printemps 1503, passe une commande à Léonard pour qu’il fasse un portrait de son épouse, celle-ci lui a déjà donné deux garçons (en mai 1496 et en décembre 1502). Voir, autre somme, Daniel Arasse, Léonard de Vinci. Le rythme du monde [1997], Paris, Hazan, 2003, p. 388-389. La rime, ici, dans les deux cas: Joconde / féconde.

3. C’est un jour après la rencontre d’André Breton, invité là, et douze jours avant que, le 17 janvier, Tristan Tzara n’arrive là pour y habiter, ce séjour coïncidant avec le début de ce que Michel Sanouillet a appelé “Dada à Paris”: voir sa somme, Dada à Paris, Paris, Pauvert, 1965. Le siège du “MoUvEmEnT DADA, Berlin, Genève, Madrid, New York, Zurich”, dit le papier à lettre qui arbore cet en-tête, est maintenant à Paris. Par ailleurs, je note la coïncidence (qui n’en était peut-être pas une en 1919, étant donné l’état des connaissances sur l’oeuvre de Léonard): lorsque Duchamp est à Paris cette année-là, les deux femmes (l’épouse et la maîtresse) de Picabia sont enceintes de garçons; lorsque Francesco del Giocondo, au printemps 1503, passe une commande à Léonard pour qu’il fasse un portrait de son épouse, celle-ci lui a déjà donné deux garçons (en mai 1496 et en décembre 1502). Voir, autre somme, Daniel Arasse, Léonard de Vinci. Le rythme du monde [1997], Paris, Hazan, 2003, p. 388-389. La rime, ici, dans les deux cas: Joconde / féconde. 4. À Cabanne, Duchamp dit Tableau dada de [sic] Marcel Duchamp.

4. À Cabanne, Duchamp dit Tableau dada de [sic] Marcel Duchamp. 5. Michel Sanouillet, Francis Picabia et “391”, tome II, Paris, Losfeld, 1966, p. 113. (Le tome I est, en fac-similé, la réédition de 391 [1917-1924] augmentée de divers documents inédits, Paris, Losfeld, 1960.) Duchamp étant à New York depuis le 6 janvier et le no 12 de 391 ne paraissant (précise Sanouillet) qu’à la fin mars, on peut penser que Duchamp, interviewé par Schwarz (The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp, New York, Abrams, 2e édition, 1970, p. 476), se souvient erronément de ce qui s’est passé à l’époque (je retraduis): “Mon original n’est pas arrivé à temps et, afin de ne pas retarder indûment l’impression de 391, Picabia a dessiné lui-même la moustache sur la Mona Lisa mais a oublié la barbiche.”

5. Michel Sanouillet, Francis Picabia et “391”, tome II, Paris, Losfeld, 1966, p. 113. (Le tome I est, en fac-similé, la réédition de 391 [1917-1924] augmentée de divers documents inédits, Paris, Losfeld, 1960.) Duchamp étant à New York depuis le 6 janvier et le no 12 de 391 ne paraissant (précise Sanouillet) qu’à la fin mars, on peut penser que Duchamp, interviewé par Schwarz (The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp, New York, Abrams, 2e édition, 1970, p. 476), se souvient erronément de ce qui s’est passé à l’époque (je retraduis): “Mon original n’est pas arrivé à temps et, afin de ne pas retarder indûment l’impression de 391, Picabia a dessiné lui-même la moustache sur la Mona Lisa mais a oublié la barbiche.” 6. Je dis “l’inscription qui deviendra le titre du readymade” car, dans le catalogue-affiche de l’exposition chez Sidney Janis, Duchamp écrit: “La Joconde, postcard with pencil”. Ce n’est qu’à partir du premier catalogue de l’oeuvre duchampienne, celui de Robert Lebel (Sur Marcel Duchamp, Paris, Trianon Press, 1959), que ce readymade a L.H.O.O.Q. comme titre. Et ce n’est qu’à partir du catalogue Schwarz (Arturo Schwarz, The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp, New York, Abrams, 1re édition, 1969) qu’on a les dimensions exactes dudit readymade: 19.7 x 12.4 cm ou 7¾ x 4⅞ pouces.

6. Je dis “l’inscription qui deviendra le titre du readymade” car, dans le catalogue-affiche de l’exposition chez Sidney Janis, Duchamp écrit: “La Joconde, postcard with pencil”. Ce n’est qu’à partir du premier catalogue de l’oeuvre duchampienne, celui de Robert Lebel (Sur Marcel Duchamp, Paris, Trianon Press, 1959), que ce readymade a L.H.O.O.Q. comme titre. Et ce n’est qu’à partir du catalogue Schwarz (Arturo Schwarz, The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp, New York, Abrams, 1re édition, 1969) qu’on a les dimensions exactes dudit readymade: 19.7 x 12.4 cm ou 7¾ x 4⅞ pouces. 7. Les deux O de “L H O O Q”, eux-mêmes au centre de deux autres O qui ont la forme de ficelles formant des 8 ou encore la forme des pales d’une hélice, mais d’une hélice sans axe et molle, courbée par le vent, sont également – et doublement – les O de “double” et de “monde”. Le petit manque, en haut à gauche, dans l’un de ces autres O n’a d’égal, en bas à droite, que le petit manque dans le À de “À DOMICILE”, une autre inscription, et que le petit supplément – la queue – du Q de “L H O O Q”. Façon de faire coïncider ironiquement spéculations mathématiques (topologie) et spéculations marchandes (livraison “à domicile”, c’est-à-dire au logis).

7. Les deux O de “L H O O Q”, eux-mêmes au centre de deux autres O qui ont la forme de ficelles formant des 8 ou encore la forme des pales d’une hélice, mais d’une hélice sans axe et molle, courbée par le vent, sont également – et doublement – les O de “double” et de “monde”. Le petit manque, en haut à gauche, dans l’un de ces autres O n’a d’égal, en bas à droite, que le petit manque dans le À de “À DOMICILE”, une autre inscription, et que le petit supplément – la queue – du Q de “L H O O Q”. Façon de faire coïncider ironiquement spéculations mathématiques (topologie) et spéculations marchandes (livraison “à domicile”, c’est-à-dire au logis). 8. “J’ai fait juste avant de quitter Paris une Joconde pour Aragon […] / Man Ray a la 1ère Joconde” (lettre de Duchamp à Jean Crotti, Villefranche-sur-mer, 6 février 1930, dans Affectionately, Marcel. The Selected Correspondance of Marcel Duchamp, édition de Francis Naumann et Hector Obalk, traduction de Jill Taylor, Gand et Amsterdam, Ludion Press, 2000, p. 171).

8. “J’ai fait juste avant de quitter Paris une Joconde pour Aragon […] / Man Ray a la 1ère Joconde” (lettre de Duchamp à Jean Crotti, Villefranche-sur-mer, 6 février 1930, dans Affectionately, Marcel. The Selected Correspondance of Marcel Duchamp, édition de Francis Naumann et Hector Obalk, traduction de Jill Taylor, Gand et Amsterdam, Ludion Press, 2000, p. 171). 9. Trois exemples: Duchamp lui-même en 1953 (voir note 6); Ecke Bonk, Marcel Duchamp, The Box in a Valise. Inventory of an Edition, New York, Rizzoli, 1989, p. 241; Calvin Tomkins, Duchamp. A Biography, New York, Henry Holt and Company, 1996, p. 221.

9. Trois exemples: Duchamp lui-même en 1953 (voir note 6); Ecke Bonk, Marcel Duchamp, The Box in a Valise. Inventory of an Edition, New York, Rizzoli, 1989, p. 241; Calvin Tomkins, Duchamp. A Biography, New York, Henry Holt and Company, 1996, p. 221. 10. Faut-il ajouter que Duchamp, dans les répliques ultérieures, n’a jamais utilisé une carte postale.

10. Faut-il ajouter que Duchamp, dans les répliques ultérieures, n’a jamais utilisé une carte postale. 11. J’utilise ici le pluriel, comme Duchamp en avril 1942 lorsqu’il indique à l’encre, au bas de la maquette de l’une des deux versions Picabia (celle qui est reproduite dans 391), “Moustaches par Picabia / barbiche par Marcel Duchamp”. En français, on dit indifféremment, par exemple, ciseau et ciseaux (car il y a deux lames), pantalon et pantalons (deux jambes), moustache et moustaches (deux joues ou, simplement, deux côtés au visage). Je note par ailleurs que l’indication technique, inscrite par Picabia sur deux lignes au crayon verticalement à droite de la reproduction, commence par deux liaisons – celle qui amorce le 1 de “1 cliché” sur la première ligne et celle qui amorce le s de “sans” sur la deuxième ligne – qui n’ont d’égal que l’extrémité des moustaches! Pour une reproduction et des commentaires, voir Francis Naumann, The Art of Making Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, catalogue de l’exposition chez Achim Moeller Fine Art, New York, 2 octobre 1999-15 janvier 2000. Si le voyage à Paris fait par Arp en avril 1942 est bien celui durant lequel il entre en possession de ces deux versions, la rencontre Arp-Duchamp (qui se connaissent depuis 1926) ne peut avoir lieu qu’en zone inoccupée (à Grasse où habite Arp, à Sanary où habite Duchamp, avant le départ de ce dernier pour les États-Unis le 14 mai).

11. J’utilise ici le pluriel, comme Duchamp en avril 1942 lorsqu’il indique à l’encre, au bas de la maquette de l’une des deux versions Picabia (celle qui est reproduite dans 391), “Moustaches par Picabia / barbiche par Marcel Duchamp”. En français, on dit indifféremment, par exemple, ciseau et ciseaux (car il y a deux lames), pantalon et pantalons (deux jambes), moustache et moustaches (deux joues ou, simplement, deux côtés au visage). Je note par ailleurs que l’indication technique, inscrite par Picabia sur deux lignes au crayon verticalement à droite de la reproduction, commence par deux liaisons – celle qui amorce le 1 de “1 cliché” sur la première ligne et celle qui amorce le s de “sans” sur la deuxième ligne – qui n’ont d’égal que l’extrémité des moustaches! Pour une reproduction et des commentaires, voir Francis Naumann, The Art of Making Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, catalogue de l’exposition chez Achim Moeller Fine Art, New York, 2 octobre 1999-15 janvier 2000. Si le voyage à Paris fait par Arp en avril 1942 est bien celui durant lequel il entre en possession de ces deux versions, la rencontre Arp-Duchamp (qui se connaissent depuis 1926) ne peut avoir lieu qu’en zone inoccupée (à Grasse où habite Arp, à Sanary où habite Duchamp, avant le départ de ce dernier pour les États-Unis le 14 mai). 12. Voir les deux cartes postales, datées 1914, reproduites dans Roy McMullen, Les grands mystères de la Joconde [1975], traduction d’Antoine Berman, Paris, Éd. de Trévise, 1981, p. 223.

12. Voir les deux cartes postales, datées 1914, reproduites dans Roy McMullen, Les grands mystères de la Joconde [1975], traduction d’Antoine Berman, Paris, Éd. de Trévise, 1981, p. 223. 13. Affectionately, Marcel, ouvr. cité, p. 272.

13. Affectionately, Marcel, ouvr. cité, p. 272. 14. C’est d’ailleurs la traduction, par Michel Sanouillet, de ce passage: “un chromo […] bon marché” (“À propos de moi-même”, dans Duchamp du signe, Paris, Flammarion, 1975, p. 227). Naumann emprunte exactement la même voie: “an inexpensive chromo-lithographic color reproduction” (The Art of Making Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, ouvr. cité, p. 10).

14. C’est d’ailleurs la traduction, par Michel Sanouillet, de ce passage: “un chromo […] bon marché” (“À propos de moi-même”, dans Duchamp du signe, Paris, Flammarion, 1975, p. 227). Naumann emprunte exactement la même voie: “an inexpensive chromo-lithographic color reproduction” (The Art of Making Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, ouvr. cité, p. 10). 15. Pierre Cabanne, Entretiens avec Marcel Duchamp, ouvr. cité, p. 115.

15. Pierre Cabanne, Entretiens avec Marcel Duchamp, ouvr. cité, p. 115. 16. Voir Michel Sanouillet, Francis Picabia et “391”, ouvr. cité, p. 166. On peut voir (391, ouvr. cité, p. 127) la signature de Carpentier et l’ajout de Picabia sous quelques-unes des lignes imprimées en caractères typographiques au bas de la page.

16. Voir Michel Sanouillet, Francis Picabia et “391”, ouvr. cité, p. 166. On peut voir (391, ouvr. cité, p. 127) la signature de Carpentier et l’ajout de Picabia sous quelques-unes des lignes imprimées en caractères typographiques au bas de la page. 17. Herbert Crehan, “Dada”, Evidence, Toronto, n 3, automne 1961. Je traduis.

17. Herbert Crehan, “Dada”, Evidence, Toronto, n 3, automne 1961. Je traduis. 18. Ces deux “O.” ne sont pas sans évoquer aussi, par la rime “O.” / eau, le lac de montagne et le lac de plaine dans le célèbre tableau, respectivement en haut à droite et un peu plus bas à gauche dans le paysage dominé par la loggia où est le modèle, Lisa. Et que dire du chemin sinueux venant du lac de plaine, répercuté dans la queue du “Q.” (calligraphié par Duchamp)?

18. Ces deux “O.” ne sont pas sans évoquer aussi, par la rime “O.” / eau, le lac de montagne et le lac de plaine dans le célèbre tableau, respectivement en haut à droite et un peu plus bas à gauche dans le paysage dominé par la loggia où est le modèle, Lisa. Et que dire du chemin sinueux venant du lac de plaine, répercuté dans la queue du “Q.” (calligraphié par Duchamp)? 19. Une phrase présentative dans une autre, le référent de “This” (Ceci, comme dans “Ceci est mon corps” ou dans “Ceci est une oeuvre d’art”) étant cataphorique (c’est-à-dire qu’il suit le pronom): dans le premier cas, c’est “the original “ready made””; dans le second cas, c’est l’ensemble de la proposition formant le premier cas.

19. Une phrase présentative dans une autre, le référent de “This” (Ceci, comme dans “Ceci est mon corps” ou dans “Ceci est une oeuvre d’art”) étant cataphorique (c’est-à-dire qu’il suit le pronom): dans le premier cas, c’est “the original “ready made””; dans le second cas, c’est l’ensemble de la proposition formant le premier cas. 20. Dans son bref article, ““Desperately Seeking Elsie”. Authenticating the Authenticity of L.H.O.O.Q.’s Back” (Tout-Fait, New York, vol. I, n 1, décembre 1999), Thomas Girst nous apprend que cette dame, installée à l’Hotel St. Regis, New York, de 1943 à 1945, est une sténographe publique.

20. Dans son bref article, ““Desperately Seeking Elsie”. Authenticating the Authenticity of L.H.O.O.Q.’s Back” (Tout-Fait, New York, vol. I, n 1, décembre 1999), Thomas Girst nous apprend que cette dame, installée à l’Hotel St. Regis, New York, de 1943 à 1945, est une sténographe publique.