Opposition and Sister Squares: Marcel Duchamp and Samuel Beckett.

Andrew Hugill

Bath Spa University, UK.

Abstract

This article explores the personal and artistic relationship between Marcel Duchamp and Samuel Beckett. It examines the biographical evidence for a connection between the two men and in particular focuses on chess. It explores some apparent evocations of Duchamp, both as a man and as an artist, in writings such as Murphy and Eleuthéria. It suggests that some key aspects of the dramatic structure, staging, and dialogue in Endgame derives from Beckett’s awareness of the peculiar endgame position described in L’opposition et les cases conjuguées sont réconciliées (Opposition and Sister Squares are Reconciled) by Duchamp and Halberstadt. To reach a detailed understanding of this argument, it sets out an expository account of a typical chess position and its accompanying terminologies from the book, then applies those to the play itself.

Paris in the 1930s

Samuel Beckett first encountered Marcel Duchamp in Paris during the 1930s. Something of the familiarity of their relationship may be deduced from this casual remark in a letter to George Reavey, written in 1938:

I am halfway through a modified version in French of Love and Lethe. I don’t know if it is better than the English version or merely as bad. I have 10 Poems in French also, mostly short, When I have a few more I shall send them to Éluard. Or get Duchamp to do it. (ed. Fehsenfeld and Overbeck, 2009, 645).

‘Love and Lethe’ was one of the stories in

More Pricks Than Kicks (Beckett, 1934, 85-100) and the poems were later to be published as part of a set of twelve as ‘Poèmes 38-39’ (Beckett, 1946, 288-293). In 1932, Beckett had translated several of Paul Éluard’s poems for

This Quarter (Éluard, 1932, 86-98). By 1935 Reavey was in the process of preparing a new collection, entitled

Thorns of Thunder, in which he intended to reprint these translations, with some more besides (ed. Fehsenfeld and Overbeck, 2009, 296-297). However, since these new translations were due at a time when Beckett was struggling to complete

Murphy, he was obliged to refuse to take on Éluard’s ‘La Personnalité toujours neuve’ (A Personality Always New), declaring that he was ‘up to [his] eyes in other work’ (Ibid. 330). He lamented to Thomas MacGreevy in a letter dated 9 April [1936]: ‘Murphy wont move for me at all. I get held up over the absurdest difficulties of detail. But I sit before it most day of most days.’ (Ibid. 331).

Some relief from the pressures of writing Murphy came from playing chess. Marcel Duchamp seems to have been an occasional opponent during this period. Deirdre Bair cites Kay Boyle, Gabrielle Buffet-Picabia, Josette Hayden, and an anonymous Irish writer and friend of Beckett, in recording that:

Beckett knew Duchamp throughout the 1930s in Paris, having met him at Mary Reynolds’ house. Beckett frequented the cafés where the best players congregated, as did Duchamp, and he followed the chess column that Duchamp occasionally wrote for the Paris daily newspaper Ce Soir (Bair, 1980, 393).

James Knowlson similarly recounts a conversation with Beckett in which he declared that he ‘played chess occasionally with Marcel Duchamp’ (Knowlson, 1996, 289). Although this statement is placed within a chapter covering the period 1937-39, there is little doubt that the acquaintance between the two artists preceded those dates. Mary Reynolds, who had begun her long-term relationship with Duchamp in 1926 (a love affair that only came to an end with her death, with Duchamp at her side, in 1950), welcomed both of them into her house in Montparnasse:

The 1930s marked a period of tranquillity, contentment, and artistic achievement for [Mary] Reynolds. Her relationship with Duchamp had settled into a comfortable intimacy. Her creativity and binding production were at their highest levels. She held an open house almost nightly at her home at 14, rue Hallé, with her quiet garden the favored spot after dinner for the likes of Duchamp, Brancusi, Man Ray, Breton, Barnes, Guggenheim, Éluard, Mina Loy, James Joyce, Jean Cocteau, Samuel Beckett, and others. (Godlewski, 2001, 12).

It is therefore no surprise to find Beckett writing with complete confidence in 1938 that Duchamp would pass the poems to Éluard, who in turn would be willing to assist in getting them published.

Murphy

Duchamp steered a studiously idiosyncratic course through Parisian intellectual life, continuing the line of Dada yet somewhat distant from it, actively involved in Surrealism yet managing to avoid becoming too close to Breton’s group. Nevertheless, in 1938 he designed the Second Surrealist Exhibition at the Galérie des Beaux-Arts. Beckett, similarly, ‘shared in the thrilling atmosphere of experiment and innovation that surrounded Surrealism’ but kept his distance ‘largely because, … they were distinctly cool, if not actively hostile, to Joyce’s own ‘revolution of the word’ (Knowlson, 1996, 107).

Murphy reflects this sense of detached engagement. The celebrated chess game in which Mr Endon methodically moves his pieces out, then moves them back to their starting positions, irrespective of Murphy’s own moves, is both dadaistically absurd and surreal, while at the same time fitting neither of those descriptors exactly. The detached and remorseless logic of Mr Endon himself, whose chess-playing is described as his ‘one frivolity’, also seems somewhat Duchampian in character:

Endon was a schizophrenic of the most amiable variety, at least for the purposes of such a humble and envious outsider as Murphy. The langour in which he passed his days while deepening now and then to the extent of some charming suspension of gesture, was never so profound as to inhibit all movement. His inner voice did not harangue him, it was unobtrusive and melodious, a gentle continuo in the whole consort of his hallucinations. The bizarrerie of his attitudes never exceeded a stress laid on their grace.

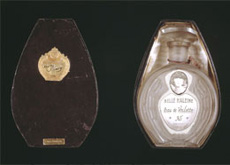

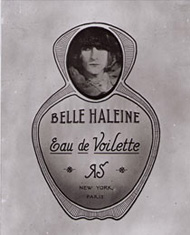

There are other seeming echoes elsewhere, for example, Neary’s avowal ‘To gain the affections of Miss Dwyer even for on short hour, would benefit me no end’, which is similar in both content and cadence to the title of Duchamp’s small glass of 1918:

To be looked at (from the other side of the glass) with one eye, close to, for almost an hour. Katherine S. Dreier, who was often referred to as “Miss Dreier”, owned the small glass at this time.

Chapter Six, which is devoted to the split between Murphy’s mind and his body, reminds one of Duchamp’s finding a way out of ‘retinal’ painting and into conceptual art and thence to chess. Duchamp famously sought to put art at the service of the mind and eschewed the physicality of ‘retinal’ painting, by adopting a ‘neutral’ style, by eliminating backgrounds from his work, by removing evidence of the artist’s hand, and finally by giving up the making of art altogether. His celebrated pursuit of the beauty of aesthetic indifference, expressed most strongly in the readymades, was also a quest for freedom: from taste, from the art world, from choice. He consciously worked within the concept of liberty that this afforded him, describing himself as a Cartesian whose ideal was the logic of chess:

Chess is a marvelous piece of Cartesianism, and so imaginative that it doesn’t even look Cartesian at first. The beautiful combinations that chess players invent – you don’t see them coming, but afterward there is no mystery – it’s a pure logical conclusion (Tomkins 1998, 211).

Beckett also made a link between indifference and freedom in Murphy:

The freedom of indifference, the indifference of freedom, the will dust in the dust of its object the act a handful of sand let fall – these were some of the shapes he had sighted, sunset landfall after many days.

While the indifference described here is not exactly the same as Duchamp’s aesthetic indifference, the sense of freedom that indifference brings, a resignation of the will in favour of an apparently insignificant move, leads us once again to their shared enjoyment of chess. Here the chess is metaphorical rather than literal Cartesianism, and tinged with Beckettian sadness and a sense of futility. The game culminates in Murphy’s resignation, both in the chess sense and in a ‘transcendental sense of disappointment’, as he realises that he is incapable of achieving Mr Endon’s hermetic detachment. The image of a head amidst scattered chessmen conjures up Duchamp’s various studies for his painting, Portrait of Chess Players:

Following Mr Endon’s forty-third move Murphy gazed for a long time at the board before laying his Shah on his side, and again for a long time after that act of submission. But little by little his eyes were captured by the brilliant swallowtail of Mr Endon’s arms and legs, purple, scarlet, black and glitter, till they saw nothing else, and that in a short time only as a vivid blur, Neary’s big blooming buzzing confusion or ground, mercifully free of figure. Wearying soon of this he dropped his head on his arms in the midst of the chessmen, which scattered with a terrible noise. Mr Endon’s finery persisted for a little in an after-image scarcely inferior to the original. Then this also faded and Murphy began to see nothing, that colourlessness which is such a rare postnatal treat, being the absence (to abuse a nice distinction) not of percipere but of percipi.

The final sentence is a reference to the famous maxim usually attributed to Bishop Berkeley:

esse est percipi (to be is to be perceived). This is itself an immaterialist reversal of the Cartesian

cogito. The absence of self-perception which Murphy achieves is an ironic ‘abuse’ of the stinction between the two. When he awakes from his trance, Murphy finds that Mr Endon has wandered off and is pressing light-switches in the corridors of the lunatic asylum in a way that seems haphazard but is in fact determined by an a mental pattern as precise as any of those that governed his chess.

All this leads to Murphy’s death. Soon after he has become a warden at the Magdalen Mental Mercyseat, he procures, with the help of the poet, Ticklepenny, the garret of his dreams. It is an attic with a single skylight that is isolated from the rest of the house. Its only drawback is that it lacks heating. While Murphy is out, Ticklepenny rigs up a contraption whose Duchampian characteristics are uncanny, consisting of a radiator that must be connected to the gas by glass tubing that flows from a WC on the floor below.

He described how he had turned it on in the WC and raced back to the garret. He explained how the flow could only be regulated from the WC, as there was no tap at the radiator’s seat of entry.

The linking of water and gas occurs throughout Duchamp’s work, most notably in

La Mariée mise à nu par ses Célibataires, même (The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, even) (1915-23), better known as the

Large Glass. The

Green Box of 1934, which contains all the notes that accompany the

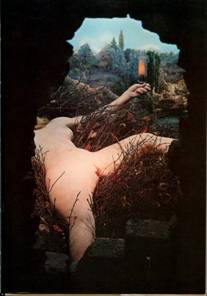

Large Glass, states: ‘Given 1. the waterfall 2. the illuminating gas’ (Sanouillet and Peterson, 1975, 27). The precise derivation of this is made clear with the ‘imitated readymade’ of 1958: a facsimile of plaques attached to certain Parisian apartment blocks, with which Beckett would have been very familiar, which read: ‘Eau et Gaz à tous les étages’ (Water and Gas on every floor). The connection between the two is continued thematically and representationally in Duchamp’s posthumous installation

Étant donnés: 1° la chute d’eau / 2° le gaz d’éclairage (Given: 1 The Waterfall, 2 The Illuminating Gas) (1946-1966).

Thus the WC resembles the Bachelor Machine, powered by a waterfall, regulated by a ballcock (in the Glass it is a bottle of Benedictine) which rises and falls by means of a hook arrangement (just as the jet is turned on by a double chain and ring). The connecting tubes function like the capillary tubes of the lower domain of the Glass. The radiator, with its apparent defiance of ignition, suggests the cool Bride whose desire magneto (coils) has to be excited before she becomes aroused/hot. The skylight evokes the Moving Inscription, allowing Murphy to look out at the stars (i.e. the Milky Way). The Illuminating Gas, powered by the Waterfall, animates the whole and brings warmth to the garret.

And what of Murphy and his imminent doom? We are already aware of his status as confirmed bachelor. We are also aware of the intensity of his longing to achieve the Endon state. Murphy resembles one of the nine ‘shots’ drilled through the Large Glass: a foreign body in the purity of the Bride, a hole in a pane of glass, a nothingness within a nothing. As he returns to the quarters of the male nurses (who, of necessity, all live below the garret) he strips bare. He leaves behind his uniform (in Duchampian parlance, his ‘malic mould’) and becomes undiluted, uncontained Gas. This loss of form and identity is shown by his inability to conjure up any images. He has become as transparent as the Glass which surrounds him. Seated in his rocking-chair (whose motion apparently resembles that of the Glider) he perceives the radiator (the Bride) before penetrating the Glass, shot through to ‘…the freedom of that light and dark that did not clash, nor fade nor lighten except to their communion.’

The consequent fireball seems to be more orgasm than apotheosis, more petit mort than Big Bang. Murphy confirms the volatile nature of the gas of which he becomes a part in his Duchamp-like proposition that ‘Chaos’ is the etymological origin of the word ‘Gas’. Now, ironically, the WC is ‘lit by electricity’, just like the Large Glass depicted in the drawing Cols Alités of 1959. The causalité that leads from Endon to the shattered skylight is the same that leads from opening move to checkmate.

Of course, none of these parallels is supported by any corroborating evidence, either in Beckett’s correspondence, or Duchamp’s writings, or in the critical literature. Yet, it does seem curious that, at a moment when chess dominates the novel, such Duchampian resonances should appear. Perhaps it is merely a matter of a certain zeitgeist which Duchamp and Beckett both succeeded in capturing, or perhaps it goes deeper than that. What is beyond doubt, however, is that the two men were about to begin a brief but meaningful association in which chess was the driving force.

Arcachon, 1940

In June 1940, the Nazis occupied Paris. Duchamp had already decided, following the fall of the Netherlands in May, to flee to the small seaside town of Arcachon on the Bay of Biscay, southwest of Bordeaux. Beckett and his partner Suzanne Descehevaux-Dumesnil (of whom he was ‘dispassionately’ fond) also fled Paris, first to Vichy and eventually joining Duchamp in Arcachon.

Accounts vary somewhat as to the extent of the presence of Mary Reynolds in Arcachon during this period. According to James Knowlson, it was ‘thanks to her kindness and generosity’ that the couple were able to find a room and, with the help of a loan from Valéry Larbaud, then to rent a house overlooking the sea: the Villa Saint-Georges, 135 bis Boulevard de la Plage (Knowlson, 1996, 300). Susan Glover Godlewski, on the other hand, reveals that despite the best persuasive efforts of Marcel Duchamp, Reynolds stubbornly refused to leave Paris, reluctantly spending no more than perhaps a month’s vacation in Arcachon (Godlewski, 2001, 15). She certainly stayed in Paris throughout the war and was an active member of the Résistance. In a letter to her brother, dated August 7th 1941, she said that she spent much time ‘tracking down food and [giving] unorganized aid’ (Ibid. 15). This ‘aid’ was resistance work, for which she was later narrowly to avoid execution.

Whatever the truth, at some point the two couples were joined by a third, the painter Jean Crotti and his second wife, Duchamp’s sister, Suzanne. The main pastime of the three men was playing chess. Beckett was ‘delighted to find that, in one move, he had acquired two new chess partners.’ (Knowlson, 1996, 301). They played regularly in a seafront café. Crotti and Beckett seem to have been fairly well matched, but Duchamp, who was a leading chess master, was, according to Beckett, ‘always too good for him. Yet he said this with the quiet satisfaction of knowing that he had played against someone of that calibre.’ (Haynes and Knowlson, 2003, 13). Both men shared an enormous admiration for the great players, as this incident in Arcachon demonstrates:

Once when Duchamp and Beckett were playing chess together, Duchamp pointed out, to Beckett’s great excitement, that the world chess champion, Alexander Alekhine (a chess genius, according to Beckett) had just walked in. (Knowlson, 1996, 301).

It is not hard to imagine that both would have agreed with Duchamp’s assertion to the New York State Chess Association banquet in 1952 that ‘the chess pieces are the block alphabet which shapes thoughts; and these thoughts, although making a visual design on the chess-board, express their beauty abstractly, like a poem … I have come to the personal conclusion while all artists are not chess players, all chess players are artists’.

Portrait of Chess Players

So what did they talk about, these two masters of the art of silence? Unfortunately no record of their conversations exists, but we may assume that it was mostly fairly casual and probably focused on the game in hand, or perhaps current affairs, or maybe life in Paris. Chess players tend not to talk during a game, although in a non-professional setting such as this that rule may be somewhat relaxed. Perhaps Duchamp, as an advanced player, gave Beckett a little tuition, if only in the form of post-game analysis. Beckett was always keen to learn more about chess and Duchamp had already published (in 1932) his book on endgames

L’opposition et les cases conjuguées sont reconciliées (Opposition and Sister Squares are reconciled), co-authored with Vitaly Halberstadt. They would certainly have enjoyed remaining quiet, but it is also rather inconceivable that they would not have discussed at least some aspects of their artistic work. Perhaps they talked about the extent to which chess was such an important force for them both.

For Duchamp, it was ‘the imagining of the movement or the gesture that makes the beauty, in [chess]. It’s completely in one’s gray matter.’ (Cabanne, 1971, 18-19). It is often stated that he gave up art for chess on his return to Paris in 1923, and it is certainly true that playing chess dominated his existence from that time (despite the secret work on the posthumously revealed installation Etant Donnés). However, it is also clear that, for Duchamp, there was little distinction between art and chess. It was ‘a logical, or if you prefer, a Cartesian constant’ that was highly important to someone who famously wished to put painting ‘at the service of the mind’ (Sanouillet and Peterson, 1975, 125).

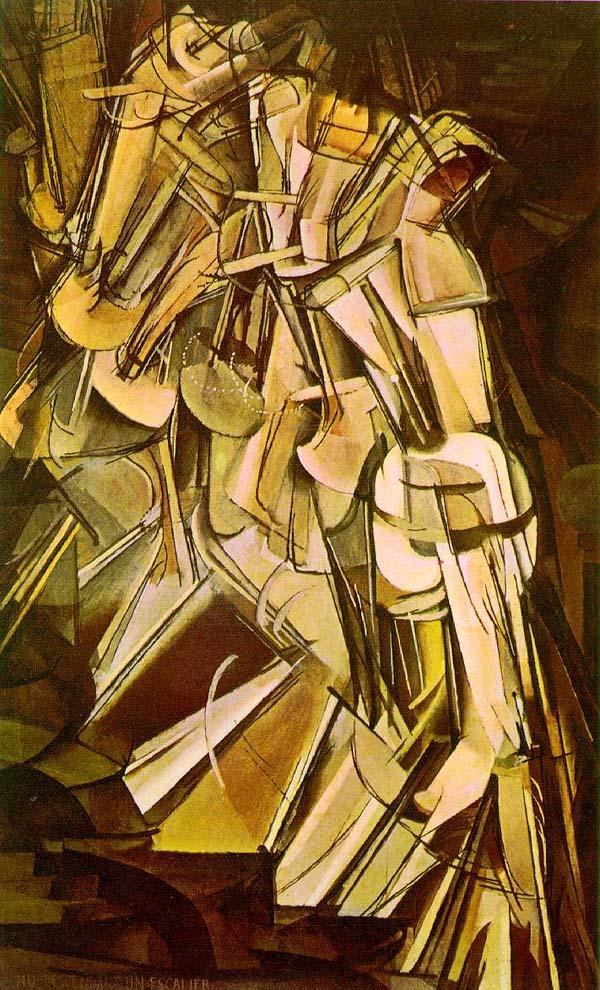

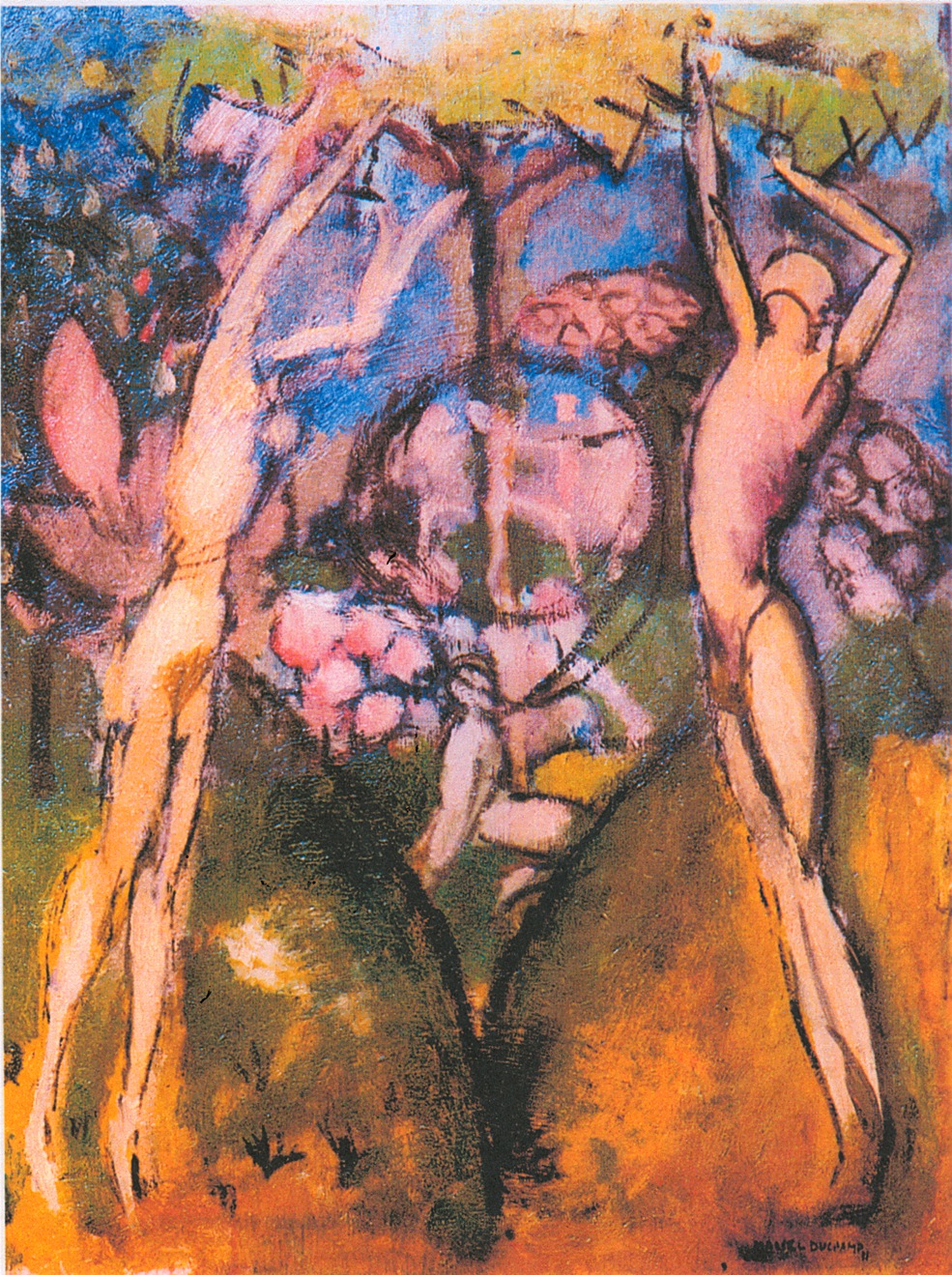

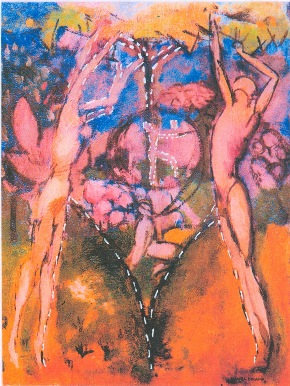

Duchamp began playing chess as a child and its presence in family life was depicted in the 1910 painting La Partie d’échecs (The Chess Game), which shows his two older brothers at the board while their wives take tea. Jacques Villon and Raymond Duchamp-Villon were the subjects once again of the Portrait de joueurs d’échecs (Portrait of Chess Players) of 1911, but Duchamp’s style had already moved on from the earlier influence of Cézanne to a reinterpretation of Cubism that was to culminate later the same year in the Nu Descendant un escalier (Nude Descending a Staircase). Duchamp commented:

I painted the heads of my two brothers playing chess, not in a garden this time, but in indefinite space … This particular canvas was painted by gaslight to obtain the subdued effect, when you look at it again by daylight.’ (d’Harnoncourt and McShine, 1973, 254).

This ‘subdued effect’ reflects Duchamp’s growing concern with removing the superfluous elements from his work. In successive pieces, the background was eliminated, becoming flat black in the

Broyeuse de Chocolat (Chocolate Grinder) of 1913 and transparent by the time of the

Large Glass. As it moved towards the condition of the chessboard, Duchamp’s art lost anything that might be considered immaterial to the ‘game’ that was being played. (

Etant Donnés finally reinstated the background, but ironically, and on a chessboard floor). Thus it acquired a certain rigour that entirely befitted his desire to achieve an aesthetic indifference that is closer to mathematics than the decorative arts.

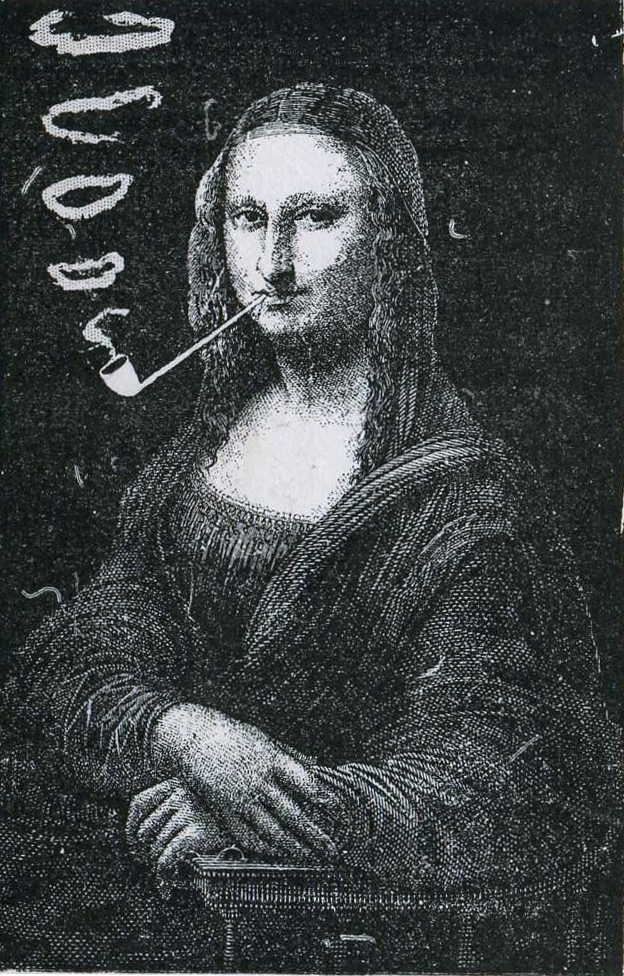

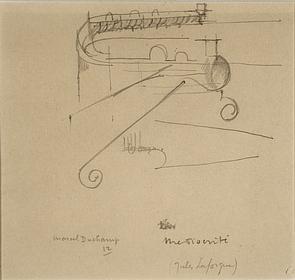

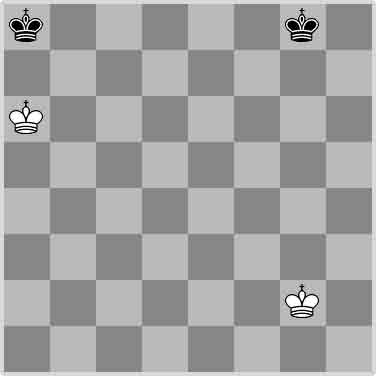

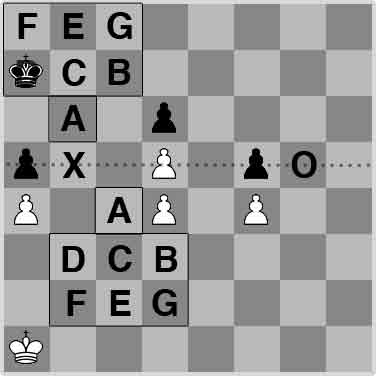

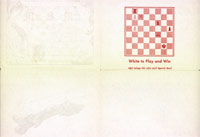

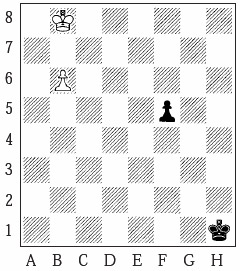

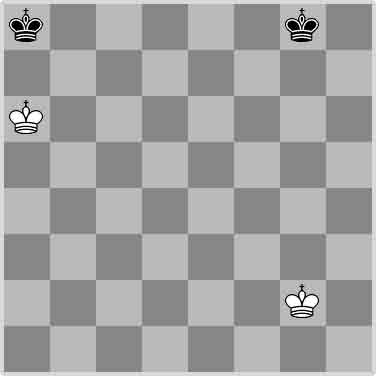

The readymades, ‘found’ objects that most epitomised this indifference, also contained allusions to chess, most notably in Trébuchet (Trap)(1917), which consists of a coat rack nailed to the floor, its four hooks uppermost. The title is a reference to this equally spiky, yet salutary, chess position (Figure 1):

-

Figure 1: Le Trébuchet (The Trap)

If Black is to play, he wins the opposing pawn by:

1. … f4-e3

2. b5-c5 e3-e4.

It would be wrong to play

1. … f4-e4

because of

2. b5-c5!

and White wins the pawn.

During his period in Argentina in 1918-19, Duchamp designed his own chess pieces and a set of rubber stamps that could be used for playing postal chess. It was also during this sojourn, socially isolated as he was in Buenos Aires, that he became so obsessed with the game that he decided to turn professional. In 1920 he joined the Marshall Chess Club in New York, and by 1923 he was participating in his first major tournament, in Brussels. In 1925, he designed the poster for the French Chess Championship in Nice. In 1931, following a tournament in Prague, he became a member of the committee of French Chess Federation and its delegate (until 1937) to the International Chess Federation. In 1932, in what was probably the best performance of his chess career, he won the Paris Chess Tournament.

In the same year, he saw Raymond Roussel playing chess at a nearby table in the Café de la Régence, but he did not have the courage to introduce himself. The influence of Roussel on the Large Glass has been well documented (Henderson 1998) and the presence of his poetic method (derived from plays on words) may be detected throughout Duchamp’s oeuvre, including the readymades and the alter ego Rrose Sélavy. Along with Alfred Jarry and Jean-Pierre Brisset, Roussel provided much of the literary underpinnings of Duchamp’s art. The fact that Roussel was also a leading chess player, who had published a celebrated solution to the difficult mate with a Bishop and a Knight alone, explains Duchamp’s nervousness at the encounter.

Duchamp took part in his last major international chess tournament in 1933, in Folkestone, England, but continued to play correspondence chess, serving as captain of the French team, in which role he remained undefeated.

Beckett shared Duchamp’s passion for chess, if not his playing ability. He (Beckett) was inspired by his uncle Howard, who had the rare distinction of having beaten Capablanca (later to become world champion) during an exhibition match in Dublin before the First World War (Knowlson, 1996, 9). Beckett also greatly admired Capablanca, whose extremely lucid playing style and influential books emphasized the importance of the endgame as the essence of chess. Beckett played enthusiastically during his schooldays and at university and, as we have seen, throughout his life, never losing an opportunity for a game. He had an extensive library of chess books, and explicitly based certain aspects of his writings on the game, most notably, of course, in Murphy and Endgame, although allusions to it appear as early as 1929 in the short story ‘Assumption’.

Opposition and Sister Squares are reconciled

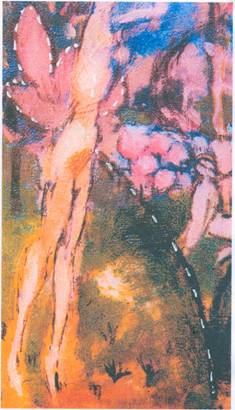

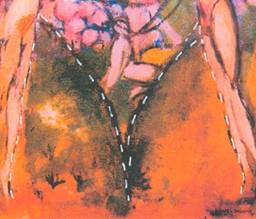

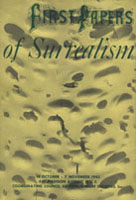

L’opposition et les cases conjuguées sont reconciliées was published in Paris and Brussels (Editions de l’Echiquier, 1932) in a limited edition. Few copies were sold, and Francis M. Naumann records that, late into his life, Duchamp “kept most of the edition in a closet, giving copies away to friends whenever he thought the gift appropriate” (Naumann and Bailey 2009, 22). The book’s design and its use of chess terminologies are both somewhat unusual for a chess textbook, and clearly resonate with themes in Duchamp’s artwork. So, for example, the illustrations frequently divide the chessboard across the middle using a dotted line as a ‘hinge’, self-consciously echoing the division of the Large Glass into two panels. To compound the allusion, eight of these ‘hinged pictures’, as Duchamp called the Large Glass (Sanouillet and Peterson, 1975, 27), are printed on transparent paper so that they may be folded to make the two principal domains correspond exactly. Here we see one variation of the instruction that was eventually to be included in the Green Box of 1934: ‘develop the principle of the hinge’.

The chess argument depends on two well-known properties that become highly important in the endgame, but Duchamp’s choice of terminologies may have had a wider significance than just their chess usage. His preference for the term ‘sister’ squares (in English) over the more commonly used ‘corresponding’ squares may be a nod towards Suzanne.The term ‘opposition’, while it does not figure much as a word in Duchamp’s notes, nevertheless occurs throughout his work as a theme, as is best exemplified by the relationship between Bride and Bachelors, in the two panels of the Glass, which are then ‘reconciled’ by the operations of that imaginary technology. The word ‘domain’ occurs particularly in the Green Box with reference to the two panels of the Glass. The ‘passage’ of the White King from secondary to principal domain echoes the passage of the Virgin to the Bride (as depicted in the canvas of that title of 1912). The principle of the opposition in chess is as follows:

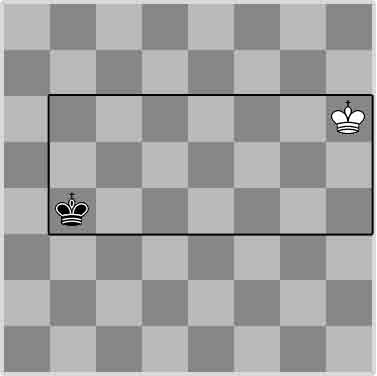

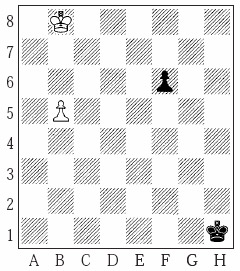

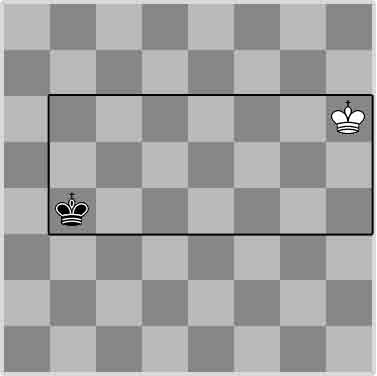

-

Figure 2: The Opposition

In Figure 2, with White to play, Black ‘has the opposition’ in both cases. a6 – a8 is direct opposition, whereas g2- g8 is distant. This is due to the rule which prevents Kings from occupying adjoining squares. The King which has the move is obliged to give ground.

-

Figure 3: Virtual Opposition

Likewise, in Fig. 3, the two Kings are in ‘virtual opposition’, because they occupy two diagonally opposed squares of the same colour which are at the corners of a rectangle.

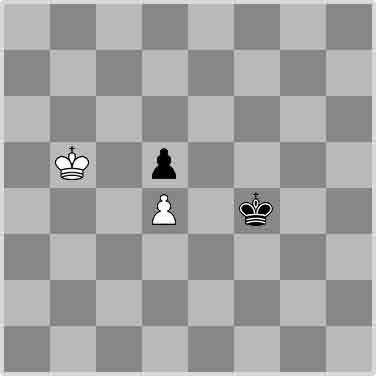

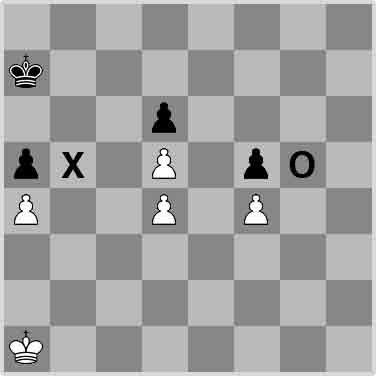

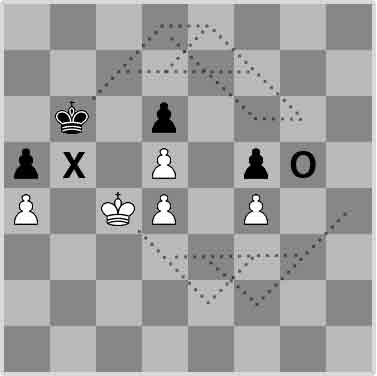

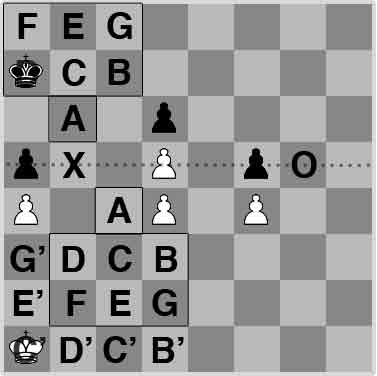

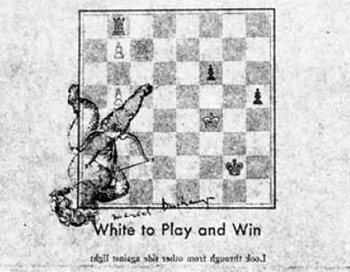

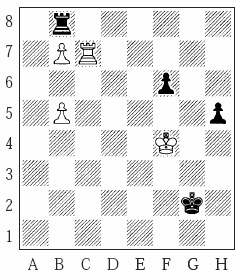

To reach a full understanding of how all this might have influenced Endgame requires a knowledge of Duchamp and Halberstadt’s book. What follows is an illustrative account of one of the positions used by the authors to illustrate their thesis. The position was composed by Emmanuel Lasker and Gustavus Charles Reichelm, and first published in the Chicago Tribune in 1901, and is still occasionally used today.

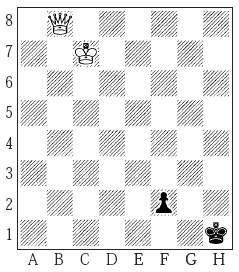

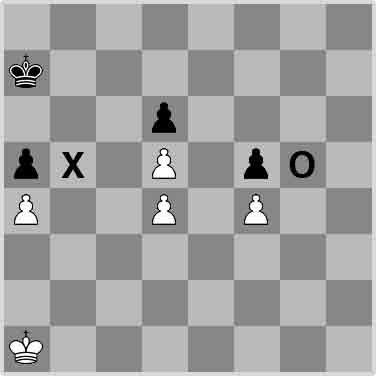

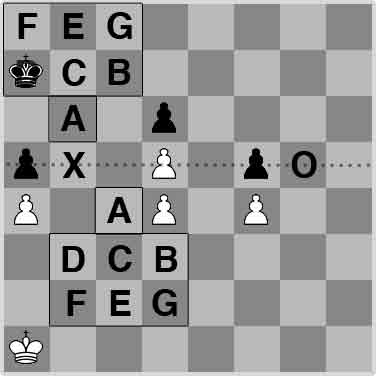

-

Figure 4: Lasker-Reichelm, 1901

In Figure 4 it is immediately clear that the pawns are unable to move. It also becomes evident that the White King can penetrate the Black position via two (and only two) squares: b5 and g5. Should he succeed in occupying either of these two squares (with or without the move) the White King will capture a black pawn (a5 or f5), thereby enabling him to promote his own pawn to a Queen on the eighth rank to win the game. The two squares b5 and g5 are called the ‘pole’ squares (X and O, respectively).

To prevent White’s King from occupying g5, Black’s King must arrive at g6 on the move after White’s reaches h4, forcing him to retreat. White, therefore, must reach h4 whilst Black is still at e8 or e7 (i.e. he is two files ahead of Black). Likewise, to prevent White from occupying b5, Black must occupy a6 or b6 on the move after White’s to c4. However, if Black chooses a6, White will be two files ahead in a race to the other pole and so Black can only prevent penetration on b6.

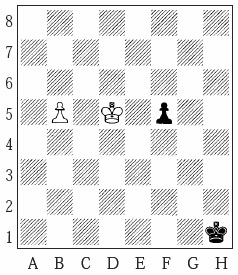

-

Figure 5: Routes

Figure 5 shows that there is not a single minimum route between the two threats for either King. One square of White’s minimum route has a unique correspondent on Black’s minimum route, namely d3 (to c7). Thus, if White moves c4-d3, Black replies ….b6-c7, and will arrive at g6 in time to prevent White from occupying O (g5). The related squares d3 and c7 are the ‘sister squares’. The pairings b6 and c4, and g6 and h4 are also sister squares.

-

Figure 6: Sister Squares

Once these sister squares have been observed, corresponding blocks may be built up: the ‘principal domains’. In Figure 6, the squares C only touch on A and B. Likewise D to A and C, and so on. The two rectangles formed by the squares B thru G are the principal domains of the White and Black Kings. The squares A are the decisive positions of the Kings at pole X, and are therefore not strictly part of the principal domains.

The two domains have the property of ‘superposition by folding’ along the hinge a5-h5. For the coincidence to be perfect, one must move the Black domain one square to the right. This fact enables us to establish a law of heterodox opposition for this position: a7 and b3 (squares D) are in heterodox opposition because the two squares are equidistant from the hinge and on right hand neighbour files. Thus the general formula for heterodox opposition in the principal domains is as follows: without the move, the White King has the heterodox opposition when he occupies, on a right hand adjacent file to the file occupied by the Black King, a square of opposite colour to that occupied by the latter.

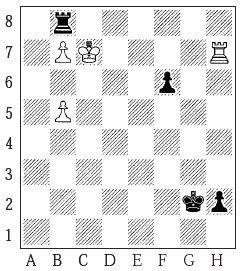

Let us suppose that the White King occupies b2 (i.e. square F in his principal domain) and he has the heterodox opposition to Black (who has the move) positioned on his own F (a8). The authors examine three possible replies for Black: 1) 1. … a8-a7; 2) 1. …a8-b7; 3) 1. …a8-b8. Of these, the second rapidly transmutes into the first.

1st Variation, after 1. …a8-a7

b2-b3 (White retains the heterodox opposition and the threat of reaching A in one move)

2. …a7-b7 (forced to remain one square from A)

3. b3-c3 (still has heterodox opposition and threat on A)

3. …b7-c7 (forced. If he plays b7-a7, White will have the two file advantage to O)

4. c3-d3 (still has heterodox opposition and threat on A)

4. … any (Black is now forced to abandon his control of A, as any move to the left will

give White a two file advantage to O. White now occupies A and wins).

2nd Variation

Becomes 1st Variation, e.g.

1. …a8-b7

2. b2-c3 etc.

3rd Variation, after 1. …a8-b8

2. b2-c2 (takes the heterodox opposition)

2. …b8-c8 (to keep White King as far as possible from A)

3. c2-d2 (retains the heterodox opposition)

3. …c8-d8 (Black cannot turn back because White will gain the two file advance. The first variation showed that …c8-c7 would be a win for White)

4. d2-c3 (White breaks the opposition, threatening to reach A in one move)

4 …d8-c7 (forced to protect A)

5. c3-d3 (reverting to the first variation, and White wins).

It is clear, therefore, that White must enter his principal domain on a square which gives him the heterodox opposition, or which does not permit Black to take it.

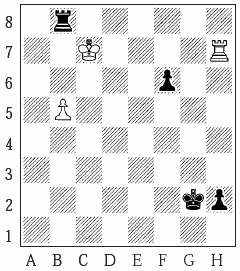

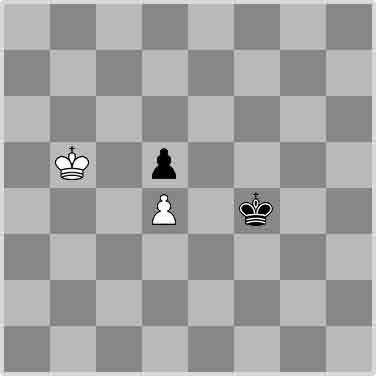

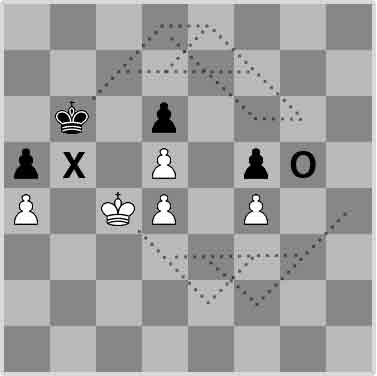

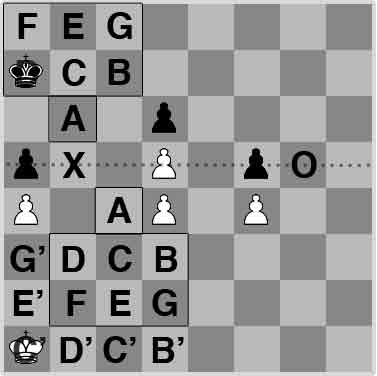

-

Figure 7: White’s Secondary Domain

In Figure 7 the dashed letters indicate the extent of the White King’s secondary domain. As we have seen, he must pass from this domain into his principal domain either by taking the heterodox opposition, or by moving onto a square which does not allow Black to take it. Thus, in Figure 7, White cannot play to b2 (F) on the first move, because Black would take the heterodox opposition by moving to a8 (F). Therefore, the best White can do is 1. al-bl (C’-D’), thereby taking the secondary heterodox opposition (on file adjacent to the right and square of opposite colour).

If Black replies 1. … a7-b7 (avoiding F and E which would allow White to enter his principal domain with the heterodox opposition, at the corresponding sister square), then White must play 2. bl-cl (D’-C’), retaining the secondary heterodox opposition.

Now Black must avoid squares F, E, G, which would allow White to enter his principal domain as before, so he plays 2. … b7-c7 (C-B).

White, as before, can only retain the secondary heterodox opposition, and must play 3.cl-dl (C’-B’).

Black cannot now play to C, E or A, because White will have the two file advantage to pole O. If he goes to c8 (G), White will enter his principal domain at d2, with the heterodox opposition, and win as we have seen. Black must play to the d file (the solution is the same for 3. …c7-d7 as 3. … c7-d8).

Now the White King can breach the opposition, by entering his principal domain at c2 (E), thereby preventing Black from taking the heterodox opposition at his sister E, and simultaneously threatening to reach c4 (A) in two moves.

Black must remain on the d file, since a move to G or B would enable White to take the heterodox opposition in the principal domain.

White replies 5. c2-c3 (E-C), remaining in breach of the opposition and threatening to reach A in one move.

Because of this, Black is forced to play 5. … (d)-c7 (C-B).

We have already seen how White will win once he has taken the heterodox opposition in the principal domain (e.g. 6. c3-d3).

The authors conclude their investigation into this position by giving a drawing variation, in order to show how ignorant play by White can ruin his chances of a win. In such a variation, Black is satisfied to take and hold the heterodox opposition, preventing penetration of his position.

Returning to the position of Figure 7 (the original position), let us assume that White foolishly plays 1. al-b2 (C’-F).

As Black has the move, he takes the heterodox opposition in the principal domain by playing 1. …a7-a8 (D-F). If the White King moves about in the principal domain, Black will follow him, always keeping the principal heterodox opposition, and will accompany him, one file behind, if he attempts to reach pole O. That is a draw. If White returns to al (C’), Black can take the secondary heterodox opposition in reverse at b7 (C).

From this, it is clear that White must leave the a-file on his first move (in the original position) and never return to it. An opening move of 1. al-a2 would lead to a draw, since Black would take the secondary heterodox opposition in reverse with the reply 1. …a7-b8 (D-E), leading to a drawn game.

In conclusion, it will be observed that the most Black can hope for is a draw. Given accurate play by White, Black can only succeed in delaying the progress of events.

Eleuthéria

The first appearance of chess in Beckett’s theatrical works occurs in the suppressed play Eleuthéria (1947). Towards the end of Act III, an ‘audience member’ delivers the following speech to the Glazier:

… if I’m still here it’s that there is something in this business that literally paralyzes me and leaves me completely dumbfounded. How do you explain that? You play chess? No. It doesn’t matter. It’s like when you watch a chess game between players of the lowest class. For three quarters of an hour they haven’t touched a single piece. They sit there gaping at the board like two horses’ asses and you’re also there, even more of a horse’s ass than they are, nailed to the spot, disgusted, bored, worn-out, filled with wonder at so much stupidity. Up until the moment when you can’t take it any more. Then you tell them, So do that, do that, what are you waiting for, do that and it’s all over, we can go to bed. It’s inexcusable, it goes against even the most elementary know-how, you haven’t even met the guys, but it’s stronger than you, it’s either that or a fit. There you have pretty much what’s happening to me. Mutatis mutandis, of course. You get me? (Beckett, 1995, 143-44).

It is this sense of frustration and despair, deriving from the inevitable decline of a chess game first identified in Murphy, but exaggerated at the hands of the idiot players (amongst whom, one suspects, Beckett might have numbered himself) who represent us all as we fail to grasp the hopelessness of our situation, that is a theme in much of Beckett’s work. The Cartesian mechanisms of chess always demand that choices are made; choices that gradually run out until, in the end, win or lose, there remain no more. Duchamp declared: ‘in art I came finally to the point where I wished to make no further decisions, decisions of an artistic order, so to speak’ (Judovitz, 2010, 109). Beckett applied the same principle to life itself.

It is interesting to note that the chess-playing protagonist of Eleuthéria is called ‘Victor’, which was the nickname given to Duchamp by Henri-Pierre Roché (the author of Jules et Jim), a close personal friend since before World War I. Roché’s unfinished novel of 1957, entitled Victor (Duchamp), is a character study. Caroline Cros observes:

The main character, Victor (Duchamp), is almost entirely absent throughout the book, yet Patricia (Beatrice [Webb]) and Pierre (Henri-Pierre [Roché]) are both utterly fascinated by him – ‘There is no danger since we both love him’ – and speak of him incessantly (Cros, 2006, 45).

This is essentially the scenario of Eleuthéria, in whichVictor is more often absent than present, yet is the main topic of conversation amongst the other characters. He constantly evades giving an account of himself, yet exerts a powerful influence, effectively ‘playing’ the other characters like chess pieces. Challenged by the Glazier, he says:

VICTOR: I look out for my welfare, when I can.

GLAZIER: Your welfare! What welfare?

VICTOR: My freedom.

GLAZIER: Your freedom! It is beautiful, your freedom. Freedom to do what?

VICTOR: To do nothing.

It was Roché who wrote the following summary of Duchamp and Halberstadt’s book:

There comes a time toward the end of the game when there is almost nothing left on the board, and when the outcome depends on the fact that the King can or cannot occupy a certain square opposite to, and as a given distance from, the opposing king. Only sometimes the King has a choice between two moves and may act in such a way as to suggest he has completely lost interest in winning the game. Then the other King, if he too is a true sovereign, can give the appearance of being even less interested, and so on. Thus the two monarchs can waltz carelessly one by one across the board as though they weren’t at all engaged in mortal combat. However, there are rules governing each step they take and the slightest mistake is instantly fatal. One must provoke the other to commit that blunder and keep his own head at all times. These are the rules that Duchamp brought to light (the free and forbidden squares) to amplify this haughty junket of the Kings (Lebel, 1959, 83).

Endgame

Ruby Cohn recounted Beckett’s own description of the scenario of Endgame, which seems to echo Roché’s text:

Hamm is a king in this chess game lost from the start. From the start he knows he is making loud senseless moves. That he will make no progress at all with the gaff. Now at the last he makes a few senseless moves as only a bad player would. A good one would have given up long ago. He is only trying to delay the inevitable end. Each of his gestures is one of the last useless moves which put off the end. He’s a bad player (Cohn, 1974, 152).

Deirdre Bair cites an unnamed Irish writer and friend of Beckett who ‘feels that any interpretation of

Fin de partie must begin with the influence of Marcel Duchamp’ (Bair, 1978, 393). The contention in the present article is that this influence goes deeper than just the basic predicament described by Roché and Cohn, and is the result of Beckett’s awareness of Duchamp and Halberstadt’s book, or at least of the endgame position it contains. While Dirk Van Hulle has confirmed that the book is not among those in Beckett’s extant library, “that does not necessarily imply that he didn’t read Duchamp’s book, because Beckett gave away many of his books to friends” (private email to the author, 5.7.13). Since Duchamp himself gave away copies of

L’opposition… it is possible that Beckett received one and passed it on. Or it is equally possible that, given their circumstances in Paris and Arcachon, the book was never actually given to Beckett, but Duchamp explained its contents to him.

Either way, its unique characteristics may be detected in the structuring of the drama, in the staging, and in some key points of dialogue. The endgame position itself is, as Duchamp himself pointed out, ‘so rare as to be nearly Utopian’ (Cabanne, 1971, 78). It almost has the status of a philosophical proposition of great theoretical purity. It is full of ironies, indeed of potential horrors. This is not just any endgame: it is the endgame to end all endgames.

The frustrations of the position described above finds expression in the way in which Black (Hamm) haphazardly delays and thwarts White (Clov). Identification of these two characters with their respective chess colours is made easy by the symbolic attributes of both: Hamm is blind, hence unaware; in a wheelchair, hence restricted; wearing dark glasses, hence ‘black’; Clov is knowing, mobile, and very frustrated.

Both the structure and content of the play echo this delayed peculiarity. Beckett’s response is poetic yet formal: the state of a player at the end of a long game. Hamm and Clov themselves represent both players and pieces (the Kings) and the whole play takes place at the next-to-end of the dramatic structure, which so strongly resembles the phases of a game of chess.

Hamm is desperate for the end of the game, yet unable to comprehend the geometry of the position: ‘Enough, it’s time it ended, in the refuge too. (Pause) And yet I hesitate, I hesitate to… to end.’

His opening cri de coeur resembles Duchamp’s note in the Green Box: ‘given that…. ; if I suppose I’m suffering a lot…’:

Can there be misery (he yawns) loftier than mine? No doubt. Formerly. But now? (Pause) My father? (Pause) My mother? (Pause) My … dog? (Pause) Oh I am willing to believe they suffer as much as such creatures can suffer. But does that mean their sufferings equal mine? No doubt.

Duchamp’s quasi-mathematical (“given that…”) statement of supposed suffering is matched by the detached, even bored (

“he yawns”), self-observation of Hamm, whose similarly quasi-mathematical qualities are revealed most clearly in the French: “Mais est-ce dire que nos souffrances se valent? Sans doute.”

The play is set in a location by the sea, one where the outside world has crumbled away to nothingness. This setting is reminiscent of Arcachon and Europe under the Nazis. The opening description of the stage set and Clov’s actions establish the Duchamp/Halberstadt position. Grey light is reflected from the surface of a chessboard. The two windows represent the two poles of the position. This is confirmed later in the play when Clov looks through both windows and describes the scene for Hamm’s benefit: ‘Light black. From pole to pole.’ (‘Light black’ also describes the alternation of white and black squares).

The two ashbins, homes of Nagg and Nell, symbolize the immobile and redundant pawns. A picture with its face turned to the wall seems perhaps to echo Duchamp’s abandonment of painting for chess. When Clov removes the picture and replaces it with an alarm clock, the echo rings louder, since, from the audience’s point of view, the clock is seen from the side, a disposition which has a source in the Green Box:

The Clock in profile

and the Inspector of Space

Note: When a clock is seen from the side it no longer tells the time.

Beckett extends this examination of a clock’s properties by having his characters listen to its alarm, as if it were a piece of music:

(Enter Clov with alarrn-clock. He holds it against Hamm’s ear And releases alarm.They listen to it ringing to the end. Pause.)

CLOV: Fit to wake the dead! Did you hear it?

HAMM: Vaguely.

CLOV: The end is terrific!

HAMM: I prefer the middle.

Notice that Hamm’s ineptitude extends even to the simplest act of listening, whereas Clov is well able to appreciate the change from activity to inactivity. Hamm prefers the cover and confusion of ceaseless activity, just as he would have preferred the multiplicity of choices in the middle-game which has ended.

Clov’s opening movements and actions serve not only to map out the position, but also tell us that he understands it, since it is he who opens the curtains on the windows and looks through them. It is as though we are seeing enacted the thought-processes of the White player, as he analyses the position using Duchampian geometry. His opening speech makes clear the facts of his position, i.e. that he is waiting for Hamm/Black to move to a suitable square, enabling him (Clov) to enter his principal domain either with or in breach of the opposition.

I’ll go now to my kitchen, ten feet by ten feet – by ten feet, and wait for him to whistle me. (Pause) Nice dimensions, nice proportions, I’ll lean on the table, and look at the wall, and wait for him to whistle me.

The kitchen, therefore, is White’s secondary domain, as the squareness of its outline suggests, and Clov is watching the wall not through boredom, but in anticipation of the moment when he will be able to penetrate it (i.e. into his principal domain) and win. The whistle is Hamm’s signal that he has ‘moved’, and occurs at several points throughout the play. We must imagine a scenario of White constantly retaining the heterodox opposition, in response to the haphazard but successful delaying moves of Black. As we have seen in the third of the winning variations of the Lasker-Reichelm position, a point must come when White is able to enter his principal domain in breach of opposition. It is at the penultimate whistle that this finally occurs and Clov is suddenly free to move – to ‘go’ – and to win. Hamm’s opening speech confirms this, and establishes him as a bad player who should have given up a long time ago. The act of wiping his glasses, pointless as it is for a blind man, suggests the absurdity of his optimism.

The ensuing dialogue begins the cataloguing of the extraordinary relationship between the two characters, which finds its parallel in the minds of two chess-players. Each is dependent upon the other for his very existence, and some degree of union is achieved (via the chessboard), yet simultaneously they are engaged upon a struggle of mutual destruction. In this particular instance, the blind Hamm is aware of impending doom, but plays entirely by his feelings, whereas Clov, unable, due to his suppressed exasperation, to pity Hamm (suppressed by necessity since this is, after all, a game of chess), plays logically (‘I love order. It’s my dream’), hampered, indeed crippled, by Hamm’s lack of understanding. If Hamm understood, he would perceive that Clov also understood, and would resign forthwith. The relationship is summed up by the idée fixe:

HAMM: (anguished). What’s happening, what’s happening?

CLOV: Something is taking its course.

Clov, of course, cannot afford to reveal his knowledge to Hamm, even if such a thing were possible.

A further curious exchange acquires significance in the light of Duchamp:

HAMM: Why don’t you kill me?

CLOV: I don’t know the combination to the larder.

The larder would be set into the wall of the kitchen. If Clov could gain access to it, there might be a quick way through the wall (i.e. from his secondary to his principal domain), but, of course, it is Black/Hamm who is preventing this solution (and thereby his own rapid death). He seems to sense this fact later, when ingenuously he promises to give Clov the combination (itself a chess term), a promise which, as Clov well knows, he cannot fulfil except by accident.

This exchange is followed by references to bicycle wheels which yet again call Duchamp to mind, and reminiscences of the recent middle-game, with its knights and pawns, of whom Nagg and Nell (who ‘crashed on our tandem and lost our shanks’) are two. During his conversation with them, Hamm reveals the depth of his feelings, confirming that he has ‘a heart in his head’ (a serious handicap for a chess player) and almost succeeds in eliciting our pity. He spoils everything with his cry: ‘My kingdom for a nightman.’

‘Nightman’ is a portmanteau-word containing the notion of a knight (i.e. a horse), black in colour (night) which will end the game in Black’s favour. As Hamm follows this futile wish with a desperate move, our suspicions of his inadequacies are confirmed. So desperate is he, in fact, that he takes comfort simply from the change of square (accomplished in the realm of the imagination, with the stage invisibly becoming the new square), and has Clov push him around its boundaries and back to the centre, straightening up fussily as a distracted chess-player (while saying ‘j’adoube’) might do with his King.

Clov quickly realises that the new move has not presented the winning opportunity (‘If I could kill him I’d die happy’) and, exasperatedly, has to help Hamm by looking through the two windows once again, but this time with a telescope. Since they describe the telescope as a ‘glass’, and they consider the view from two separate panes, one is once again unavoidably reminded of Duchamp. The blue sea and sky seen through one window, and the earth colours through the other, suggest the ‘Bride’ and ‘Bachelor’ panels of the Large Glass. The telescope also seems to owe something to the iconography of the Large Glass. Clov observes the audience through it, with the comment: ‘That’s what I call a magnifier.’ Duchamp included a maginfiying lens in the small glass To be looked at (from the other side of the glass) with one eye, close to, for almost an hour, and intended to include one in the Large Glass, in the position eventually occupied by the Mandala.

Clov’s lack of pity for Hamm becomes more understandable as the play proceeds; indeed, we share his frustration. In tones of whining, threatening bombast Hamm prevaricates, delays and digresses. In the end, he makes a complete fool of himself, wildly predicting that Clov will lie down, like a resigning King. Hamm is even hoping to Queen a pawn, that is to say, Mother Pegg, whose death he will not believe.

The culminating folly is his attempt to move with the aid of the gaff, an attempt which fails, and fails again towards the end of the play when he makes a last effort to understand the position. It is at this point that the spectre of Duchamp appears, in a form resembling Mr Endon:

HAMM: I knew a madman once who thought the end of the world had come. He was a painter – and engraver. I had a great fondness for him. I used to go and see him, in the asylum. I’d take him by the hand and drag him to the window. Look! The sails of the herring fleet! All that loveliness! (Pause) He’d snatch away his hand and go back into his corner. Appalled. All he had seen was ashes. (Pause) He alone had been spared. (Pause) Forgotten. (Pause) It appears the case is… was not so…unusual.’

In chess terms Hamm’s long speech seems to be a description of the careless play in the preceding middle-game, which has led to his present predicament. It would appear that, at some point one of Black’s Knights left a pawn unguarded. We have already heard that the place is full of corpses (i.e. taken pieces) and now Hamm moves once more, still aware of the hopelessness of his position, and still unable to understand it:

I’ll soon have finished with this story. (Pause) Unless I bring in other characters. (Pause) But where would I find them? (Pause) Where would I look for them? (Pause). He whistles. (Enter Clov.) Let us pray to God.

This move appears to mark a turning-point in the drama. Clov seems more confident. His feet have stopped hurting. He is beginning to put things in order. He is cool with Hamm who, in his turn, is still more desperate, as he perceives that at last he is losing. A pawn dies. Hamm parades his area, ‘sees’ the pole points, senses his defeat, but still cannot understand the position. He contemplates resigning (by lying down), but cannot, clinging foolishly to some hope:

Perhaps I could push myself out on the floor. (He pushes himself painfully off his seat, falls back again.) Dig my nails into the cracks and drag myself forward with my fingers. (Pause) There I’ll be, in the old refuge, alone against the silence and..(he hesitates).. the stillness. If I can hold my peace, and sit quiet, it will be all over with sound and motion, all over and done with.

Instead, he moves again – disastrously. This penultimate move, then, is the one in which Whlte enters his principal domain in breach of opposition and, as we saw in the Lasker-Reichelm position, must win. The final exchanges between Hamm – and Clov serve to point up the absurdity of the position and, once again, the difference in play between Black and White:

HAMM: Do you know what’s happened?

CLOV: When? Where?

HAMM: (violently) When! what’s happened? Use your head, can’t you? What has happened?

CLOV: What for Christ’s sake does it matter?

HAMM: Before you go…(Clov halts near door)… say something.

CLOV: There is nothing to say.

HAMM: A few words…to ponder…in my heart.

CLOV: Your heart!

Coda

On the 10th January 1958, Marcel Duchamp and his wife Teeny attended the theatre in New York. In a letter to Henry McBride, he noted: ‘We saw, and loved, Endgame of Beckett.’ (Caumont and Gough-Cooper, 1993, 10-12 January).

References

Adorno, Theodor W. (1982) “Trying to Understand Endgame,” New German Critique, 25, pp. 119-150

Bair, Deirdre (1980), Samuel Beckett: A Biography, London: Picador.

Beckett, Samuel [1934] (1994), More Pricks Than Kicks, New York: Grove Press.

Becket, Samuel [1938] (1994), Murphy, New York: Grove Press.

Beckett, Samuel (1946), ‘Poèmes 38-39’, Les temps Modernes, 2.14, pp. 288-293.

Beckett, Samuel [1947] (1995), Eleuthéria, New York: Foxrock.

Beckett, Samuel [1957] (1976), Endgame, London, Faber.

Caumont, Jacques and Gough-Cooper, Jennifer (1993), Marcel Duchamp, London: Thames and Hudson.

Cabanne, Pierre (1971), Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, London: Thames and Hudson.

Cohn, Ruby (1974), Back to Beckett, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Cros, Caroline (2006), Marcel Duchamp, London: Reaktion.

Éluard, Paul (1932) [Selected Poems], (Tr. Samuel Beckett), This Quarter 5.1, pp. 89-98.

d’Harnoncourt, Anne and McShine, Kynaston (1973), Marcel Duchamp, Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Fehsenfeld, Martha Dow and Overbeck, Lois More (eds.) (2009) The Letters of Samuel Beckett Volume I: 1929-1940, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gontarski, S. E. (ed.) (2010) A Companion to Samuel Beckett. London: Wiley/Blackwell.

Haynes, John and Knowlson, James, (2003) Images of Beckett, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Henderson, Linda Dalrymple (1998), Duchamp in Context, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Judovitz, Dalia (2010), Drawing on Art: Duchamp and Company, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Knowlson, James (1996), Damned to Fame: The Life of Samuel Beckett, London: Bloomsbury.

Lane, Richard (ed.) (2002) Beckett and Philosophy, Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Naumann, Frances M. and Bailey, Bradley (eds.) (2009), Marcel Duchamp: The Art of Chess, New York: Francis M. Naumann Fine Art, LLC.

Reavey, George (ed.) (1936), Thorns of Thunder: Selected Poems of Paul Éluard, (Tr. Samuel Beckett, Denis Devlin, David Gascoyne, et al.), London: Europa Press and Stanley Nott.

Restivo, Giuseppina (1997), ‘The Iconic Core of Beckett’s Endgame: Eliot, Dürer, Duchamp’, in Engelberts, Matthijs (ed.) Samuel Beckett: Crossroads and Borderlines. Amsterdam: Rodopi, pp. 111-124.

Roché, Henri-Pierre (1959), ‘Souvenirs de Marcel Duchamp’, in Lebel, Robert (ed.) Sur Marcel Duchamp, New York: Grove Press, pp. 79-87.

Sanouillet Michel and Peterson, Elmer (eds.) (1975), Marchand Du Sel: The Essential Writings of Marcel Duchamp, London: Thames and Hudson.

Schwarz, Arturo [1969] (2001) ,The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp. New York: Delano Greenidge.

Shattuck, Roger and Watson Taylor, Simon (eds.), (1965) Selected Works of Alred Jarry, London: Methuen, 1965.

Shenk, David (2006), The Immortal Game: A History of Chess, London: Doubleday.

Tomkins, Calvin (1998) Duchamp: A Biography. London: Random House.

Wood, Beatrice (1976), Oral history interview with Beatrice Wood, available at http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-beatrice-wood-12423 (accessed 15 January 2012).

Notes

I. Duchamp’s column was published every Thursday from 1937 to the outbreak of war. Ce Soir was edited by Louis Aragon.

II. The shapes of the three Inscriptions in the Cinematic Blossoming of the Bride were created by suspending meter squares of delicate gauze or lace above a radiator (also in front of an open window), photographing the resulting movements in the rising heat, and carefully transcribing their outlines onto the Glass.

III. It should perhaps be put on record at this point that, in a conference on ‘Art and Chess’ at the Tate Gallery, London, in 1991, Mme. Teeny Duchamp, the artist’s widow, insisted that Marcel Duchamp had never played chess with Samuel Beckett. Quite what the motivation was for this denial is unclear, but the abundant evidence, however anecdotal, seems to contradict Teeny completely. She was herself a keen chess player, and had first met Duchamp in 1923. She married Pierre Matisse in 1929, and renewed her acquaintance with Marcel only in 1951, when they were married.

IV. Despite this history, Duchamp’s highest chess level was only Master (rather than Grandmaster). Out of nineteen tournament matches played between 1924 and 1933, his record was one win, eleven losses and seven draws.

V. In 1933, Duchamp translated Eugene Znosko-Borovsky’s book on chess openings into French, as Comment il faut commencer une partie d’échecs. This study of the other end of a chess game rather complements his own publication on endgames.

VI. Note that I have used the English, algebraic, square-naming chess notation, as opposed to the piece-naming system used by the authors.

VII. Roché began calling Duchamp ‘Victor’ after a dinner in New York on January 22nd, 1917 (Caumont and Gough-Cooper 1993, 21-22 January).

VIII. Further correspondence between the present author and Deirdre Bair has failed to reveal the identity of this ‘Irish writer’.

IX. In his famous essay on Endgame, Adorno suggests that Hamm’s name refers to a castrated Hamlet, with the consequent associations of melancholy and blackness.

X. This note, in turn, originates in Alfred Jarry’s Gestures and Opinions of Dr. Faustroll, Pataphysician: ‘Why should anyone claim the shape of a watch is round – a manifestly false proposition -since it appears in profile as a narrow rectangular construction, elliptic on three sides; and why the devil should one only have noticed its shape at the moment of telling the time? – Perhaps under the pretext of utility. But a child who draws the watch as a circle will also draw a house as a square, as a facade, without any justification…’ (Shattuck and Watson Taylor, 1965, 193).