click to enlarge

Charles Henri Ford in

his New York apartment,

age 87 (2 May 2000)

In addition to writing surrealist literature, being a photographer and creating art objects, Charles Henri Ford (b. 1913 in Mississippi) edited such avant-garde magazines as Blues and View. As Alan Jones wrote in Arts Magazine, “Ford opened the pages of his ‘newspaper for poets’ to the swarm of European surrealists (Max Ernst, Yves Tanguy, André Breton, Marcel Duchamp) and the returning native sons and daughters all fleeing Europe for New York. Bridging the worlds of literature and art, View rapidly grew into an art magazine the likes of which the United States had never seen.”

Charles Henri Ford, together with Parker Tyler, authored the omnisexual novel The Young and the Evil, published in Paris in 1933 and banned in the United States and England for fifty years. His ambitions as a writer and editor brought him in contact with authors like William Carlos Williams, Wallace Stevens, Jean Cocteau and especially Djuna Barnes, for whom he typed up Nightwood in Morocco while visiting Paul and Jane Bowles. Ford became an early supporter of Pop Art and a crucial influence on Andy Warhol and his circle. Active as ever, he has recently shown his poster designs at the Ubu Gallery, New York and is preparing a publication of his latest collection of haikus.

On May 2, 2000, we met with a lively Ford, and his close friend, performance artist Penny Arcade, in Ford’s New York apartment to discuss, among other topics, a 1945 issue of View magazine devoted to Marcel Duchamp, which contained Ford’s poem about the artist, “Flag of Ecstasy.” We brought our copies of View to ask him about several curiosities.

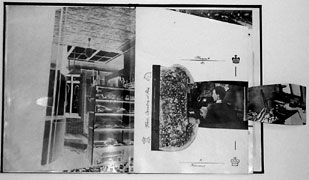

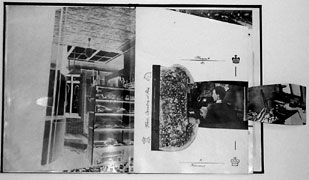

click to enlarge

1922 – STIEGLITZ – 1972

Marcel Duchamp At

The Age Of 35

Marcel Duchamp At The

Age Of 85

View, Marcel Duchamp Number, vol. 5, no. 1 (March 1945), p. 54 (detail)

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS/N.Y., ADAGP/Paris

Rhonda Roland Shearer: Do you know who took the photograph Duchamp at the Age of 85 that was published in the back of View’s Duchamp issue of March 1945?

Charles Henri Ford: You see that was an oversight, one never knew. The one to its left, showing Duchamp in 1922 is Stieglitz, isn’t it?

R.S. Yes that’s what it says but it doesn’t say who took the other one.

C.H.F. That’s right.

R.S. Some people said that this was a double, somebody that looked like Duchamp. But I think it’s Duchamp, and you know it is.

C.H.F. Oh yeah, of course it is. Otherwise it wouldn’t be, it wouldn’t …

R.S. …mean anything?

C.H.F. … it wouldn’t work. Duchamp was heavily made up to look old.

R.S. But you don’t remember who took the photograph?

C.H.F. Maybe I never even knew.

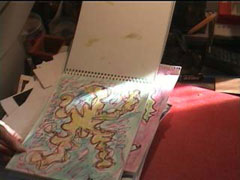

click to enlarge

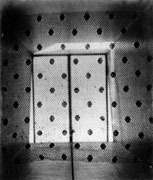

Charles Henri Ford, “Flag of Ecstasy,”

published in:View, vol. 5,

no. 1 (March 1945), p. 4

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp,

ARS/N.Y., ADAGP/Paris

R.S. Page four of View magazine reproduces your poem “Flag of Ecstasy,” an homage to Duchamp, superimposed on a detail of Man Ray’s “Dust Breeding”, showing the lower part of the Large Glass. How did this come about, “Dust Breeding” with your poem on it?

C.H.F. Well, it’s something that the printer superimposed.

R.S. Did you pick it out for your poem or did Parker Tyler who did the typography of your Poets for Painters, published in the same year and also reproducing “Flag of Ecstasy”?

C.H.F. I don’t remember … so much water under the bridge, I can’t remember.

R.S. It’s a fabulous poem.

Thomas Girst: Your poem on Duchamp is a great one.

C.H.F. You like it?

T.G. Yes, I do.

R.S. Could you read it for us? Do you read your poetry still?

Click here for video (QT 3.5MB)

Charles Henri Ford reading

“Flag of Ecstasy”

C.H.F. Why, yes.

Over the towers of autoerotic honey

Over the dungeons of homicidal drives

Over the pleasure of invading sleep

Over the sorrows of invading a woman

Over the voix celeste

Over vomito negro

Over the unendurable sensation of madness

Over the insatiable sense of sin

Over the spirit of uprisings

Over the bodies of tragediennes

Over tarantism: “melancholy stupor and an uncontrollable

desire to dance” Over all

Over ambivalent virginity

Over unfathomable succubi

Over the tormentors of Negresses

Over openhearted sans-culottes

click to enlarge

Charles Henri Ford,Poems for Painters,

New York: View Editions, 1945 (cover)

Over a stactometer for the tears of France

Over unmanageable hermaphrodites

Over the rattlesnake sexlessness of art-lovers

Over the shithouse enigmas of art-haters

Over the son’s lascivious serum

Over the sewage of the moon

Over the saints of debauchery

Over criminals made of gold

Over the princes of delirium

Over the paupers of peace

Over signs foretelling the end of the world

Over signs foretelling the beginning of a world

Like one of those tender strips of flesh

On either side of the vertebral column

Marcel, wave!

Penny Arcade: Marvelous.

R.S. Great, wonderful, beautiful. Thank you

C.H.F. I’m out of practice, I don’t read. People ask me

to read and I don’t usually read. But you win.

click to enlarge

Frederick J. Kiesler and Marcel Duchamp,

center fold-out tryptich for View,

vol. 5, no. 1 (March 1945)

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp,

ARS/N.Y., ADAGP/Paris

R.S. I thank you, we love your work. Tell us about the Frederick J. Kiesler fold out in View’s Duchamp number. You said that was very expensive to do. It’s beautiful. Do you like it?

C.H.F. Yes, sure. It cost a lot of money. I think it broke our budget.

R.S. So what do you remember in terms of Duchamp and Kiesler doing this? Were they pushing you to, saying it had to be done?

C.H.F. No, they just turned it in.

R.S. Yup, and you just liked it and had to do it.

C.H.F. Yeah, I thought that I would risk all.

R.S. Yeah, that’s what art is about, isn’t it? Who is Peter Lindamood that wrote the “I Cover the Cover.” as an introduction to the View magazine of March 1945? Is that just a pseudonym?

C.H.F. No. Peter Lindamood was from Mississippi, he was a corporal in the military and so on.

P.A. Was he a friend of yours from Mississippi?

C.H.F. Yes he was, yes. He edited a special Italian number, didn’t he?

P.A. I don’t know.

click to enlarge

Marcel Duchamp,front cover

for View magazine,

vol. 5, no. 1 (March 1945),

© 2000 Succession Marcel

Duchamp, ARS/N.Y., ADAGP/Paris

Marcel Duchamp,back cover

for View magazine,

vol. 5, no. 1 (March 1945),

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp,

ARS/N.Y., ADAGP/Paris

R.S. And so he apparently worked very hard on this issue, the Duchamp issue, it says. What this talks about is that he heard that Duchamp went through a lot of trouble to make this special effect for the cover and apparently there’s all sorts of levels of trick photography in making this cover. Do you recall?

C.H.F. No.

R.S. But it’s beautiful.

C.H.F. Yes it is.

click to enlarge

Marcel Duchamp,

cover for André Breton’s

Young Cherry Trees Secured

Against Hares, New York, 1946,

© 2000 Succession Marcel

Duchamp, ARS/N.Y., ADAGP/Paris

R.S. Another of Duchamp’s covers for View Editions, “Young Cherry Trees Secured Against Hares,” André Breton’s collected poems, shows the Surrealist’s face through a cut-out, thus posing as the Statue of Liberty. Did you ask Duchamp to make this cover?

C.H.F. Yes. Duchamp always liked to be surprising and Breton of course was noted for not cherishing homosexuals. That’s why André Breton was put in drag.

T.G. Breton supposedly liked the cover.

C.H.F. He liked any attention that was paid to him. I mean nobody was publishing his poetry in America.

T.G. That was the only translated volume of poetry resulting from his time in New York.

click to enlarge

Charles Henri Ford

flipping through his current

sketchbook (2 May 2000)

C.H.F. And then he came out with another edition too and they didn’t use his cover somehow. But its all water under the bridge…what I’ve been doing for the past few years is taking up where Matisse left off, doing cut outs and things but it was limited to the female sex so I’ve been making up for his neglect. I’ll show you an example.

R.S. Originally you’re from Mississippi?

C.H.F. Born in Mississippi, raised in Tennessee, if you don’t like my peaches, don’t you shake my tree.

T.G. From Columbus, Mississippi you started Blues in 1929, the short-lived poetry magazine which Gertrude Stein once praised as “the youngest and freshest of all the little magazines which have died to make verse free.” You were only 16 when its first issue came out.

C.H.F. Now I’m 87, about the same as Balthus and Cartier-Bresson.

T.G. And Balthus is still doing as well as you are.

P.A. Did you know Balthus?

C.H.F. I met him, once.

T.G. He’s very reclusive, Balthus. He lives in a tiny village in Switzerland, Rossinière, in a little chateau, with a beautiful wife maybe 40 years his minor.

P.A. Fascinating … we should send a message to Balthus, “Charles Henri Ford says ‘Hi.’ Still alive…”

T.G. “…we’re still standing, alive and kicking.”

R.S. Did you know the librarian at the Morgan library,

her name was Belle Greene? Did you know her?

C.H.F. No.

R.S. She was the woman that put the library together for Morgan. And she knew a lot of the artists, she posed nude for a lot of the artists and actually wrote an article in 291 and was hanging out with Stieglitz. I don’t know if you ran into her.

C.H.F. No. If she ran into me, I didn’t feel it. (An air of flirtation ensues.) Penny looks always surprised when she’s not at all surprised.

P.A. Not at all surprised. It’s your latent bisexuality.

C.H.F. Not only latent, it was executed.

R.S. Really?

P.A. Oh, yes. You can join the ranks of women like Frida Kahlo.

R.S. So does this mean that I have a chance?

C.H.F. Huh?

P.A. He doesn’t want to understand you.

R.S. He pretends he doesn’t. Does this mean I have a chance?

C.H.F. Oh. Yeah.

T.G.Your entry for the Dictionary of Literary Biography mentions your submission of a poetic prose piece to Readies for Bob Brown’s Machine. Your contribution of 1931 was intended for a Reading Machine that allowed readers to speed the words past their eyes via reels and a crank. The streamlined sentences should be as far away from conventional books as sound motion pictures were from the stage. You simply eliminated all punctuation and capital letters.

C.H.F. e.e. cummings did that too

P.A. One of the things that’s unusual about Charles is that he actually acknowledges other artists. Once I said to Charles, “One of the things that I really love about you is that you promote other artists.” And you said, “I don’t promote other artists,” and I said, “But you published other writers, you promoted other writers,” and you said, “I wasn’t promoting other artists, I was exercising my taste.”

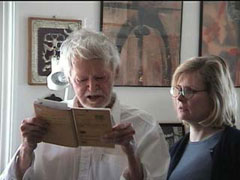

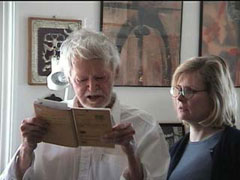

click to enlarge

Charles Henri Ford

reading a haiku

T.G. And you still write poetry, right? You write haikus.

C.H.F. Only haiku… I have a thousand page book I think of haiku and a friend of mine is going to make a typescript for that book.

T.G. Do you write them daily, haikus?

C.H.F. Yeah, I guess so, but I don’t make a point of it. If they come to me, I have to write them down quick, otherwise they fly out of my head.

R.S. Would you read a couple?

C.H.F. Good with the bad

Charles is ready when you are

Good with the bad, what does that mean?

Unbelievable! Somebody’s going to type up all of those for a big book.

Let the other people be homosexual,

As for him,

He’s not that queer

R.S. How about this one?

C.H.F. To my unexpected

Nude niece: “Get out of here,

You look like a bum!”

T.G. In 1924 Duchamp published something more longingly on the themes of nieces: “My knees are cold because my niece is cold.”

C.H.F. Oh yeah.

T.G. I actually have another question about him for you.

C.H.F. Well, let’s see if I know the answer.

T.G. In recent years, Duchamp scholars like Amelia Jones and Jerold Seigel have discussed Duchamp’s possible bi- or latent homosexuality, a claim that seems solely supported by Duchamp in drag as Rrose Sélavy and other androgynous themes running through his oeuvre. Bisexual? Marcel?

T.G. Mm-hm.

C.H.F. Yeah, he’s really a real actor.

Picture Gallery: Charles Henri Ford

click images to enlarge

Charles Henri Ford,

“Irving Rosenthal as l’Epoux Abandonné, Poem Poster Series, 1964/65 courtesy of Ubu Gallery,

New York

Charles Henri Ford,

“Fallen Womane”, Poem Poster Series, 1964/65 courtesy of Ubu Gallery,

New York

Charles Henri Ford,

“Jane as Jane” (Violet/Blue), Poem Poster Series, 1964/65 courtesy of Ubu Gallery,

New York

Charles Henri Ford,

“One of the World’s Giant Queens,”, Poem Poster Series, 1964/65 courtesy of Ubu Gallery,

New York

Four more haikus by Charles Henri Ford

Weeping and wailing

And grinding of teeth … you don’t

Have to go below

I don’t know if I’ve

Settled down or not but I’m

Not moving for now

You haven’t changed she

Said I thought I looked a

Little better I said

If it’s worth reading

Once it’s worth reading twice so

You know where to start

We are grateful to Penny Arcade and Indra Tamang, Ford’s longtime personal assistant and frequent collaborator, for making this interview possible. For more information on View, we recommend Charles Henri Ford (ed.), View: Parade of the Avant-Garde, 1940-1947 (with a preface by Paul Bowles), New York: Thunder Mouth, 1991

The interview was conducted at Charles Henri Ford’s New York apartment on May 2, 2000. It is preserved in part as a digital videotape (filmed by Martin Samsel) and available in full on audiocassette. © ASRL, 2000.