click images to enlarge

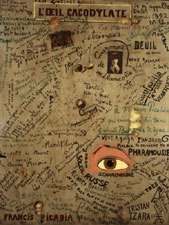

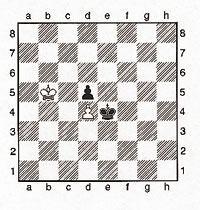

Figure 1A

Man Ray, Portrait of Marcel Duchamp, 1920

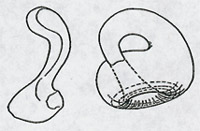

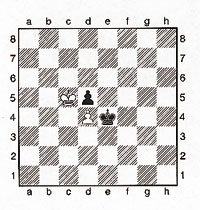

Figure 1B

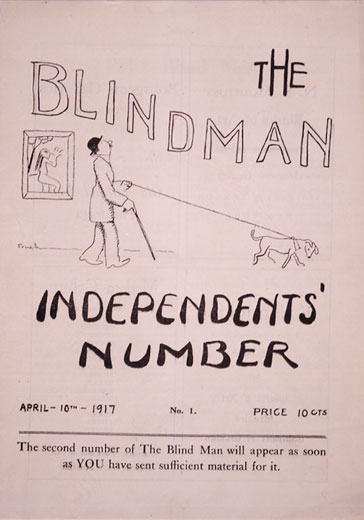

Marcel Duchamp, Cover of “The Blindman No. 1, ” April 1917

(detail of the drawing by Alfred J. Frueh)

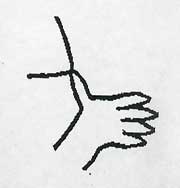

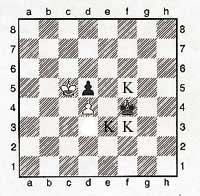

Figure 2A

Man Ray, Portrait of James Joyce, 1922

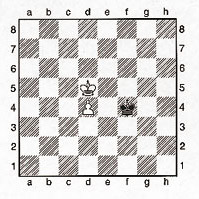

Figure 2B

Drawing by James Joyce for Finnegans Wake (1939), p. 308.

Is Marcel Duchamp the model for a character in James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake?

Yes.

Is this character attractive? No.

Does this character have an equally unattractive twin brother based on Joyce? Yes.

Finnegans Wakeis unique in our history: never has a work of literature been so widely known by name yet so rarely read cover to cover. Its fame rests in part on the fact that its author was already world famous from earlier works when it was first published. And the reason for its relative neglect by readers can be explained by even a cursory glance at any one of its 626 pages: Joyce, it would seem, had practically invented a new language, roughly based on English. Offsetting the neglect of the novel by the public at large is the humming worldwide industry of Joyce scholars who are busily earning Ph.D’s trying to decipher it.

There are many parallels between Marcel Duchamp (Fig. 1A)(who earned necessary money teaching French to Americans) and James Joyce (Fig. 2A)(who earned necessary money teaching English to Europeans). If Finnegans Wake was unprecedented in literary history, Duchamp’sLarge Glass was no less so in the history of art. Like Joyce, Duchamp was already world famous from earlier work by the time the world saw the mold-shattering new work. In the case of both the artist and the writer, that earlier work was considered extremely difficult by the general public, and was embraced only by a very small number of sympathetic artists; with the Glass and the Wake, Duchamp and Joyce respectively reached a point in their odysseys where their sympathy for the ease of their audience was very close to nil. (Fig. 1B and 2B)

Duchamp, though the younger by five years, was considerably earlier than Joyce in reaching this iconoclastic stage. For all its difficulties, Ulysses, written between 1914 and 1921, contains many passages that readers of the time could relatively easily accept as viable literature. Duchamp’s 3 Standard Stoppages, 1913–1914 (Fig. 3), and Bottle Dryer, 1914 (Fig. 4), on the other hand, were decidedly not considered viable by art lovers when they appeared on the scene.

click images to enlarge

Figure 3

Marcel Duchamp, Three Standard

Stoppages, 1913-14.

Figure 4

Marcel Duchamp, Bottle Dryer,

1914/1964.

click to enlarge

Figure 5

Marcel Duchamp, The Bride Stripped

Bare by Her Bachelors, Even, 1915-23

Duchamp made his first drawings for parts of The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even (a.k.a. The Large Glass) (Fig. 5) in 1912, began the piece itself in 1915, and stopped working on it in 1923. He made his last additions to it in New York before mid-February of that year, when he left for Europe. Joyce started Finnegans Wake on March 10, 1923. It seems a marvelous coincidence that Duchamp ended work on his unprecedented artwork only a few weeks before Joyce started work on his unprecedented book; a person of a metaphysical bent, believing in some sort of transmigrating artistic energy, might posit a scenario out of the coincidence. The writer Calvin Tomkins pointedly connects the most ambitious and notable work of the artist with that of the writer: “The Large Glass stands in relation to painting as Finnegans Wake does to literature, isolated and inimitable; it has been called everything from a masterpiece to a hoax, and to this day there are no standards by which it can be judged.” “Masterpiece” and “hoax,” of course, are the two labels most often attached to Finnegans Wake as well.

*

We maintain that beginning with Jarry . . . the differentiation long considered necessary between art and life has been challenged, to wind up annihilated as a principle.

—André Breton

Alfred Jarry:There is great wisdom in modeling one’s soul on that of one’s janitor. 1902

James Joyce: I have a grocer’s assistant’s mind. 1925.

Marcel Duchamp: I live the life of a waiter.1968.

A snow shovel? A bottle rack? A bicycle wheel? A focus on the ordinary was a significant feature of Duchamp’s contribution to the visual arts. With his Readymades he sought to elevate mass-produced objects into art’s realm. And he made clear that he considered the idea behind this gesture the most important of any that had come to him.

There is a parallel in Joyce’s transparent insistence that the ordinary is extraordinary. This interest was apparent to other writers: Richard Ellmann, his biographer, tells us that “to [William Butler] Yeats, Joyce was too concerned with the commonplace.” Ellmann himself states, “The initial and determining act of judgment in [Joyce’s] work is the justification of the commonplace.” This tendency can be seen in Joyce’s day-to-day proceedings as well as in his writing. To his friend the bookstore proprietor Sylvia Beach, for example, he said, “I never met a bore.” (Nicely parallel is Duchamp saying that he never saw a painting from which he was unable to get something of interest.) Like Duchamp, too, Joyce was capable of de-emphasizing the inventive genius of the originating author in favor of some more generic principle of creativity: speaking of Finnegans Wake to Eugene Jolas, founder of the literary review transition, he said, “This book is being written by the people I have met or known.” To a substantial degree this statement could apply even to Joyce’s early novel Stephen Hero and the collection of stories Dubliners, but it rings ever truer as we travel through Ulysses and then Finnegans Wake, with its “hero” H. C. Earwicker, also referred to as “Here Comes Everybody.”

In harmony with this, we find that Ulysses, notwithstanding its structural debt to the Homeric epic, lays out a single day in the life of middle-class citizens of Dublin. AndFinnegans Wake, for all its complex structure and portmanteau words, tells of a tavern keeper, his wife and his three children, yet again in Dublin, Joyce’s native town.

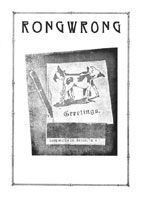

One of Duchamp’s many contributions to modern art, of course, was the willful use of the principle of chance, seen most vividly in the early Three Standard Stoppages, 1913-14. A few years later he ordered the title of the magazine he launched in 1917 to be Wrongwrong, but a printing mistake transformed it into Rongwrong. The error appealed to him and he accepted the title. Joyce too, according to Ellmann, “was quite willing to accept coincidence as his collaborator.”

Once or twice he dictated a bit of Finnegans Wake to Beckett . . . in the middle of one such session there was a knock on the door which Beckett did not hear. Joyce said, “Come in,” and Beckett wrote it down. Afterwards, he read back what he had written and Joyce said, “What’s that ‘Come in’?” “Yes, you said that,” said Beckett. Joyce thought for a moment, then said, “Let it stand.”

Authors and critics have found tonal similarities in the work of Duchamp and of Joyce. Ellmann, for example, remarks of Finnegans Wake that its “mixture of childish nonsense and ancient wisdom had been prepared for by the Dadaists and Surrealists.” This complements Michel Sanouillet’s statement that “perhaps no one was . . . more spiritually dada than Marcel Duchamp. In [him] are joined the essential elements of the dada revolt.”

Duchamp, who said that his notes for The Large Glass were part of the piece, often repeated that all of his work was based on literature. In the 1910s he said, “I felt that as a painter it was much better to be influenced by a writer than by another painter.” In 1922, meanwhile, the year after the publication of Ulysses and a year before he began Finnegans Wake, Joyce said that his writing owed much to painting. He can actually be seen as striving toward an end result more typical of painting than of writing: after suggesting to a friend that he could compare much of his work in Ulysses to a page of intricate illuminations in the Irish monastic volume The Book of Kells, he continued, “I would like it to be possible to pick up any page of my book and know at once what book it was.” And he wrote to Lucia, his daughter, “Lord knows what my prose means. In a word, it’s pleasing to the ear. And your drawings are pleasing to the eye. That is enough, it seems to me.”

Both Duchamp and Joyce would have been at a loss without female patronage. In Duchamp’s case, Katherine Dreier was sufficiently devoted to have sometimes followed the artist in his travels—whether invited or not—and named him the executor of her will; she bought the Large Glass from Duchamp’s early supporter Walter Arensberg, and held on to it. In Joyce’s case we find Beach and Harriet Weaver, among others. Both men, however, were known to treat women unfeelingly, and Joyce at times could sound sexist: granting that some women “have attained eminence in the field of scientific research,” he could add, “But you have never heard of a woman who was the author of a complete philosophical system, and I don’t think you ever will.” Yet he admitted in a letter: “throughout my life women have been my most active helpers.”

The Readymades and The Large Glass have been lauded or vilified as the end of art as we used to know it, and critics made similar comments on the publication of Finnegans Wake. Joyce himself remarked of his book, “I’m at the end of English.” Yet, despite these and a slew of other connections and parallels, no essay to my knowledge has appeared discussing the possibility of a significant personal connection between these two uniquely influential geniuses. My explorations tell me that a single essay can only serve as introduction to the subject.

Joyce and Duchamp, both international figures by the 1920s, moved in the same social circles, yet no biography of either man mentions a meeting of the two. This writer, who was on friendly terms with the artist’s late widow, Teeny Duchamp, once asked her whether she was aware of any meeting or contact between Joyce and Duchamp. She answered that she was not. The only evidence I’ve found that strongly suggests they may have met is in a short biography of the American bookbinder and art patron Mary Reynolds, who “held an open house almost nightly at her home at 14 rue Halle [in Paris], with her quiet garden the favored spot after dinner for the likes of Duchamp, Brancusi, Man Ray, [André] Breton, [Djuna] Barnes, [Peggy] Guggenheim, [Paul] Eluard, Mina Loy, James Joyce, Cocteau, Samuel Beckett, and others.” Since Duchamp was all but living with Reynolds at the time, the likelihood that he and Joyce did not meet diminishes as a possibility.

click to enlarge

Figure 6

Marcel Duchamp, Nude Descending

a Staircase, No. 2, 1912

Figure 7

Marcel Duchamp, Photograph of Fountain

by Alfred Stieglitz, 1917

Whether they met or not, however, I believe that Duchamp was the model for a character in Finnegans Wake, and by no means a sympathetic one. But this is consistent with Joyce’s world outlook; it is probably true of most of the hundreds of characters from past and current history with whom he filled his book. Duchamp’s fictional re-creation, I believe, had to do not only with his presence and reputation in Paris but with more particular considerations having to do with his personality and his relationships. In the years we are focusing on he enjoyed as wide a celebrity in the visual arts as Joyce did in the literary world. And their respective positions dovetailed extraordinarily: both known to the cognoscenti as possessing enormous abilities, both considered bad boys by the larger public. Largely responsible for Duchamp’s bad reputation was Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, 1913 (Fig. 6), andFountain, 1917(Fig. 7), the notorious upended urinal exhibited as art; for Joyce it was the four-letter words in Ulysses, never before seen or permitted in legitimately published English novels. Duchamp’s “scandal” had been widely publicized in 1917 when New York’s protectors of public morals refused to exhibit the urinal on the grounds that it was “immoral” or “vulgar.” In Joyce’s case the refusal to allow Ulysses entry into various countries on identical grounds was important news. Duchamp lived to seeFountain attain status as one of the most important artworks of the twentieth century; Joyce lived to see a similar destiny for Ulysses.

A few details about Duchamp’s relationship with American art patron Mary Reynolds and with the American collector John Quinn may help to explain why Joyce painted the character I find he based on Duchamp in such colors as he did. If this interpretation is correct, the surprise is compounded by the fact that neither Duchamp nor Reynolds is mentioned at all in Ellmann’s massive and highly detailed biography of the writer.

Duchamp and Joyce actually lived within blocks of each other at various times in Paris in the ’teens and 1920s. They were also close to many of the same people. Both Constantin Brancusi and Man Ray, for example, probably the two artists closest to Duchamp, made celebrated portraits of Joyce: Brancusi executed two true-to-life drawings of him followed by a totally abstract one that became famous and was eventually the frontispiece for Ellmann’s biography; Man Ray’s 1922 photograph of Joyce may be the most haunting portrait of a writer or artist ever made by Ray. Samuel Beckett, who met Joyce in 1928, was quite close to both the writer and the artist, as was Reynolds, although in a different way. Yet although Joyce must have seen a great deal about Duchamp in the Paris press, and no doubt heard intimate stories about him from excellent personal sources, there is only sparse documented evidence that Joyce and Duchamp even knew of each other’s existence.

click to enlarge

Figure 8

Marcel Duchamp, Cover of

transition, no. 26, 1936

One has to search to find them acknowledging each other. In 1937, when a reproduction of Duchamp’s 1916 Combreadymade was chosen as the cover of an issue of transition(no. 26) (Fig. 8)—the same issue that featured an installment of Joyce’s Work in Progress (the working title of Finnegans Wake)—Joyce intriguingly told Beach, “The comb with thick teeth shown on this cover was the one used to comb out Work in Progress.” The comment, I would argue, suggests some kind of connection between Joyce and Duchamp that no biographer to my knowledge has yet explored. In Duchamp’s case I know of two references to the writer. Once, telling Dore Ashton in a 1966 interview how some authors were famous in the way of an expensive Swiss chocolate while others were famous more in the way of Pepsi-Cola, Duchamp remarked that Joyce was in the latter category. And in 1956, in a book introduction, he wrote of Reynolds’s “close friendship with André Breton, Raymond Queneau, Jean Cocteau, Djuna Barnes, James Joyce, Alexander Calder, Miro, Jacques Villon, and many other important figures of the epoch.”

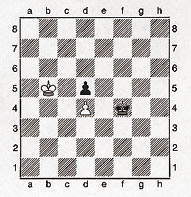

click to enlarge

Figure 9

Marcel Duchamp, Opposition

and Sister Squares Are Reconciled, 1932

Reynolds, one of Joyce’s inner circle, was also a “lifelong friend” of Joyce’s perennial intimate Beckett; the two writers would sometimes meet at her house. Joyce’s son Giorgio likewise stayed there at the same time as Beckett. It was in Reynolds’s house that Beckett started his relationship with Peggy Guggenheim, and they lived there for a short while after. Beckett and Reynolds were kindred spirits who would eventually both work bravely for the French Resistance. (Joyce, meanwhile, made a point of saying that he was not physically brave; Duchamp similarly once remarked that his response to an invasion would be to stand with folded arms.) Beckett’sEndgame, was to an extent inspired by a chess book Duchamp had co-written, Opposition and Sister Squares Are Reconciled (Fig. 9).

This same Mary Reynolds loved Duchamp with an undying fervor. Their sexual relationship survived hell and high water, including Duchamp’s strange, short-lived marriage to a plump, not overly attractive, well-to-do woman. His liaison with Reynolds began in 1924, and “in spite of his refusal to let it impinge on his freedom, it lasted for the better part of two decades.” Duchamp’s friend Henri-Pierre Roché who introduced them, would later write in his journal,

She suffers. Marcel is debauched. Has loved, perhaps still loves, very vulgar women. He holds her at arm’s length at the edge of his mind. He fears for his freedom. She wants to attach herself to him as he

says. (Mary’s eyes moisten with offended sweet pride.) . . . He comes to see her every day. Hides their relationship from everybody. Doesn’t want her to speak to him at the Café du Dome when they see each other each evening. Hides her. Gets out of their taxi a hundred yards before arriving at the home of friends. She loves him, believes him incapable of loving. . . . Just as a butterfly goes for certain flowers, Marcel goes straight for beauty. He could not go for Mary, but he protects against her his life, his calm, his solitude, his chess game, his amorous fantasies.

If Joyce objected to Duchamp’s treatment of Reynolds, it was not due to middle-class prudishness: one of his closest intimates was the Irish tenor John Sullivan, whose “family life was deeply entangled between a wife and a mistress.” Joyce himself may have remained with Nora Barnacle, the woman who loved him, until the end of his life, but a letter of 1904 to an aunt in Dublin suggests inner cravings for an independent existence; with his and Nora’s first child, Giorgio, not yet five months old, he wrote that as soon as he earned some money from his writing he intended to change his life: “I imagine the present relations between Nora and myself are about to suffer some alteration. . . . I am not a very domestic animal—after all, I suppose I am an artist—and sometimes when I think of the free and happy life which I have (or had) every talent to live I am in a fit of despair.” He did stay with Nora, marrying her in 1931, when he was forty-nine, after twenty-seven years of cohabitation. Yet around that time he told Jolas, “When I hear the word ‘love’ I feel like puking.” Nora for her part, after being cajoled by friends, not for the first time, into returning home to her penitent husband after she had fled his drunken behavior, said in 1936, “I wish I had never met anyone of the name James Joyce.” Yet Joyce, when not under the influence, obviously felt a powerful attachment to Nora. In 1928–29, when she was sent into the hospital for operations twice within a four-month period, he refused to be separated from her, and “had a bed set up in her room so that he could stay there too.”

As far as women were concerned, then, Duchamp seemed callous and acted accordingly; Joyce could speak callously and behave boorishly, but proceeded loyally. Oddly, each artist got into an inverse relationship with the same male associate, the American lawyer and collector John Quinn. In 1919, when an antiques dealer offered to sell the definitive version of Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, Quinn decided that $1,000 was “much too steep.” But in July of that year he and Duchamp met and apparently hit it off. Quinn, a fellow bachelor and, like Duchamp, a “well-known connoisseur of pretty women,” would eventually buy Brancusi sculptures through Duchamp, find a job for the artist when he needed one, and take French lessons from him for a fee. Once, “deciding that Duchamp looked tired and thin, Quinn sent him a railroad ticket and a paid hotel reservation for a few days’ vacation . . . in an . . . ocean resort on the New Jersey shore. Duchamp showed his gratitude by dashing off a pen and ink sketch of the collector and presenting it to him ‘en souvenir d’un Bontemps a Spring Lake.’”

Joyce was a less comfortable beneficiary of Quinn’s patronage. In March 1917 Quinn sent Joyce money, but only in return for the manuscript of Exiles. He also wrote a laudatory review of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man in Vanity Fair, and later he would buy the manuscript of Ulysses. But Joyce never agreed with Quinn on the value of his manuscripts, and he told Ezra Pound that he did not consider Quinn generous. When Quinn tried and failed to defend Ulysses against obscenity charges in an American court, Joyce was critical of his legal strategy, clearly believing that a different approach would have brought more chance of success. And he cannot have been pleased to learn that Quinn had told the publisher whom he had unsuccessfully represented, “Don’t publish any more obscene literature.” The only friendly thing Ellmann reports Joyce saying about Quinn came after the collector’s death, in 1924.

All the evidence shows that Joyce expected help from everyone in reach. He firmly believed in his own greatness and was not shy of trading on it. Duchamp may have had as solid a core of self-confidence, but while he took help where he could get it, he did not behave as though it were his birthright. Much more adept at navigating life’s breakers than Joyce, he seems to have been widely admired and even loved. Despite his clear refusal to make a commitment to Reynolds, for example, she remained devoted to him until her death. I met Duchamp once, engaging in a twenty-minute conversation with him the year before his death; the strong impression I was left with of his personality could best be described as “natural Zen aplomb.” Others who were very close to him agree with this evaluation with hardly a qualification. The vivid contrast with Joyce is everywhere evident. A somewhat related illustration appears in Ellmann: “Beckett was addicted to silences, and so was Joyce; they engaged in conversations which consisted often of silences directed toward each other, both suffused with sadness, Beckett mostly for the world, Joyce mostly for himself.”

* * *

On June 8, 1927, in Paris, Duchamp married Lydie Sarazin-Levassor, the granddaughter of a successful manufacturer. (They would divorce in about half a year.) “The unavoidable conclusion seems to be,” writes Tomkins, “that Duchamp had made a cold-blooded decision to marry for money. . . . When [he] learned at the formal signing of the marriage contract, in the presence of lawyers representing both parties, that the sum Lydie’s father was prepared to settle on her came to only 2,500 francs a month (slightly more than $1,000 in today’s terms of exchange), Duchamp did not immediately back out. He turned pale, according to Lydie, but he signed the contract.” That same summer Joyce composed a connective episode in his ‘Work in Progress’ (later titled Finnegans Wake)—an insert between two previously completed segments, “The Hen” and “Shem the Penman”—including several pages that seem to me rife with uncomplimentary allusions to Duchamp. Since the content of these aspersions typically involves avarice, the timing of the writing supports the suspicion of a connection between this insertion and Duchamp’s newsworthy marriage. The section of Finnegans Wake that we’re about to explore was written three years after Quinn’s death and the start of Duchamp’s relationship with Reynolds, and only weeks after the marriage that some of Duchamp’s friends saw as a Dadaist joke.

I suspect that Joyce’s Professor Ciondolone is based in the main on Duchamp. My caution stems from the knowledge that few characters in the Wake are based on a single person, evidence of the universality of certain human traits as Joyce saw them. The brothers Burrus and Caseous, for example, are temporary stand-ins for the twin brothers Shem and Shaun, two of the book’s five main characters; for Ellmann the twins in Finnegans Wake were “every possible pair of brothers or opponents.” One such opponent among Joyce’s contemporaries was the writer and artist Wyndham Lewis, whom Joyce sometimes seems to pair up with himself in Finnegans Wake—Lewis was a sometime friend who had heavily attacked Ulysses in his book Time and Western Man. But when Burrus and Caseous become stand-ins for Shem and Shaun for about five pages, I believe they are largely based on Duchamp and Joyce. If this analysis is accurate, Quinn would be their commonly shared source of milk. Consistent with the idea of twins, they seem at times to exchange personality traits, just as Shem and Shaun periodically do. In the commentary that follows, it is important to keep in mind that almost all of Joyce’s descriptions in the Wake make multiple allusions to a dizzying variety of reference points. In focusing on Duchamp, I am effectively forcing into the background the other references that I’m confident are also present. I fully expect other Sherlocks, perhaps without even arguing with my basic analysis, to have different interpretations. For all we’ll ever know, all may have some kernel of truth.

* * *

My heeders will recoil with a great leisure how at the outbreak before trespassing on the space question

where even michelangelines have fooled to dread I proved to mindself as to your sotisfiction how his abject

all through (the quickquidQuick buck.of Professor Ciondolone’s

too frequently hypothecated Mortgaged, i.e., borrowed.Bettlermensch)Bettler(German): beggar, so “beggarman.”is nothing so much more than a mere cashdime however genteel he may want ours, if we please (I am speaking to us in the second person),

The phrase suggests the idea of twins on which Joyce will elaborate below. for to this graded intellecktuals dime is cash and the cash system.

you must not be allowed to forget that this is all contained, I mean the system, in the dogmarks of origen on spurios) Darwin’Origin of Species, i.e., the survival of the fittest. think of Duchamp’s statement, “In a shipwreck it’s every man fohimself.means that I cannot now have or nothave a piece of cheeps Cheese.in your pocket at the same time and with the same manners as you can now nothalf or half the cheek apiece I’ve in mind

and Caseous

have not or not have seemaultaneously sysentangled themselves, selldear to soldthere, once in the dairy days of buy and buy. Both Duchamp and Joyce sold to Quinn, exchanging their wares—art or manuscripts—for “milk” to free them from the needs of normal labor. Burrus,let us like to imagine, is a genuine prime, the real choice Cheese. full of natural greace, Grease, grace.the mildest of milkstoffs yet unbeaten as a risicide

and, of course, obsoletely unadulterous

whereat Caseous is obversely the revise. Rival, reverse. of him and in fact not an ideal choose by any meals, though the betterman of the two is meltingly addicted to the more casual side of the arrivaliste case Arriviste—perhaps Joyce’s view of Duchamp (second definition: an unscrupulous, vulgar social climber; a bounder).and, let me say it at once, as zealous Jealous.over him as is passably he.

Probably the “art question,” as opposed to the “literature question.” The reverse, the “time” question, brings to mind Lewis’s Time and Western Man, with its attack on Ulysses.

Great artists

Feared to tread.

His object, but conceivably a reference to what I believe Joyce must have considered abject behavior on Duchamp’s part: marrying someone he thought wealthy, and in church (both Duchamp and Joyce were outspoken atheists), while deserting Reynolds, a woman of real value in the estimation of Joyce and his circle

Quick buck.

ciondolone (Italian): idler, lounger. Breton had famously accused Duchamp, the chess bum, of being an idler, wasting his great intellegence.

Bettler(German): beggar, so “beggarman.”

The phrase suggests the idea of twins on which Joyce will elaborate below.

In 1924 Duchamp had spent a month on the Riviera, “experimenting with roulette and trente-et-quarante at the Casino, trying out various systems. In a letter to [Francis] Picabia, Duchamp described in . . . detail his attempts to work out a ‘martingale,’ or system, for winning at roulette. He had been winning regularly, he said, and he thought he had found a successful pattern. ‘You see,’ he said, ‘I have ceased to be a painter, I am drawing on chance.”

Darwin’Origin of Species, i.e., the survival of the fittest. think of Duchamp’s statement, “In a shipwreck it’s every man fohimself.means that I cannot now have or nothave a piece of cheeps Cheese.

Possibly a reference to the wealthy Quinn: both Joyce and Duchamp wanted their bread buttered by the same knife, and the question was whether there would be enough butter for both of them.

Cassius, but also caseous: cheesy.

demarcation line) with a cheese dealer’s pass.” Did he have such a pass going back to the mid-twenties?

Both Duchamp and Joyce sold to Quinn, exchanging their wares—art or manuscripts—for “milk” to free them from the needs of normal labor.

Cheese.

Grease, grace.

Regicide—Brutus and Cassius conspired to kill Caesar. Also risus (Latin): laugh—so perhaps killer of laughter?

If Burrus is Joyce in this passage (Joyce also appears as Caseous, but Caseous and Burrus at times seem to switch personalities), he may be describing himself here as a faithful husband, and therefore obsolete—especially in the face of Duchamp’s recent behavior, interrupting a three-year-old affair with Joyce’s friend Reynolds in order to marry – to all appearances – for money (a marriage that Duchamp’s circle unanimously, and accurately, believed would be short-lived).

Rival, reverse.

Arriviste—perhaps Joyce’s view of Duchamp (second definition: an unscrupulous, vulgar social climber; a bounder).

Jealous.

Can possibly be. Perhaps Joyce is saying that each twin is jealous of the other.

We’ll leave Burrus and Caseous for awhile. My reading has Caseous and Burrus as temporary stand-ins for Shem and Shaun. They mainly represent Duchamp and Joyce. They’re the twins – butter and cheese- in competition for the milk from Quinn; and they are both close to many Reynolds, although in very different ways. I believe there is a strong likelihood that Duchamp’s abrupt discarding of Reynolds in favor of what was widely perceived as a marriage of convenience was a significant motivating factor in his rewriting the passage. It appears on pages 160 and 161 of the Viking edition. This is section I.vi, first published in transition, No.6, Sept. 1927, a few months after Duchamp’s very public marriage in Paris. The timing could not be better if this interpretation is on the mark.

The year of 1927, and particularly its first half, contains much of interest to one delving into a connection between Joyce and Duchamp. “The Ballad of Persse O’Reilly,” from a section of Finnegans Wake that Joyce revised for publication in June 1927, contains many references that seem likely connections to Duchamp. Here are lines leading up to “The Ballad”:

leave it to Hosty, frosty Hosty,

leave it to Hosty for he’s the mann to rhyme the ran, the rann, the rann, the king of all ranns.

Figure 10

Marcel Duchamp, Opposition and

Sister Squares Are Reconciled, 1932

Have you here? (Some ha) Have we where? (Some hant) Have you hered? (Others do) Have we whered? (Others dont) It’s cumming, it’s brumming! The clip, the clop! (All cla) Glass crash.

The (klikkaklakkaklaskaklopatzklatscha

battacreppycrottygraddaghsemmihsam

mihnouithappluddyappladdypkonpkot!).

“Frosty” a possible reference to Duchamp’s Why Not Sneeze Rrose Selavy, 1921, with it’s marble cubes resembling ice cubes

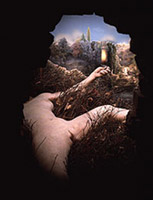

Possibly a reference to Duchamp’s notes, which are full of repetitions, and his 1917 magazine titled “rongwrong.” Its cover shows two dogs closely examining and/or smelling each other’s posteriors, just as dogs are wont to do in life. (Fig. 10).This was a very provocative image to see on the cover of a magazine at that time. In view of Joyce’s sexual proclivities it would seem that such a magazine cover might well have been noted. E.g. – from a letter, James Joyce to Nora Barnacle, Dec. 2, 1909: “I have taught you to swoon at the hearing of my voice singing or murmuring to your soul the passion and sorrow and mystery of life and at the same time have taught you to make filthy signs to me with your lips and tongue, to provoke me by obscene touches and noises, and even to do in my presence the most shameful and filthy act of the body. You remember the day you pulled up your clothes and let me lie under you looking up while you did it? Then you were ashamed even to meet my eyes.” [52A] And in another letter four days later he tells Nora of his desire to “smell the perfume of your drawers as well as the warm odour of your cunt and the heavy smell of your behind.” [52B] One other connection to Duchamp’s exploring canines is Joyce’s own primitive ink drawing reproduced on page 308 of the Wake, a close-up of a thumb-nosing, vulgarily translated as “kiss my ass!”

Remembering that Joyce later seems to be calling Duchamp (Caseous) a beggar man (Bettlermensch), we find in Roland McHugh’s Annotations to Finnegans Wake, “Ir. children used to take a wren from door to door collecting money on St. Stephen’s Day. They chanted: The wren, the wren, The king of all birds &c (U.481)—‘wren’ pronounced like ‘rann’.” [53] Perhaps, then, Joyce is dubbing Duchamp “the king of all beggars” here.

Here we have “Glass crash,” followed by the third 100-letter word denoting a “thunderclap” in the book. “Glass crash” and the thunder clap word were among the additions Joyce made to the text for its publicationin transition in June 1927; the opening of the “Ballad,”on the other hand, was already present in the first draft, writtenin 1923. Meanwhile, accordingto the accounts of the breaking of The Large Glass, thatevent took place a few months before Joyce made his additionsto this section of Work in Progress. This may be coincidence;from everything given to us as fact by Duchamp and [Katherine]Dreier, Joyce could not have known of the breaking of The LargeGlass—according to Duchamp, he himself did not hear of ituntil several years later. Bearing in mind, though, that “Glasscrash” and the thunderclap are followed immediately by the firstlines of the “Ballad”—“Have you heard of one Humpty Dumpty/Howhe fell with a roll and a rumble)”—we may wonder whether, since The Large Glass was a very large and complex “painting” and etching on glass rather than on a more durable traditional

support, Joyce was making a sarcastic prediction. Through Reynolds, he could well have known that Duchamp had worked on the Glass for the better part of a decade before leaving it “definitively

unfinished,” and that everyone including the artist considered it his most important work. This may be Joyce’s poetic way of saying, “Glass has been known to break.” We have seen him comparing his pages in Ulysses not with conventional painting but with The Book of Kells, created in or around the eighth century; perhaps he was staking his claim to a longer duration for his work than for Duchamp’s. He could even have been manifesting a kind of envy: Although he was uninterested in, even disdainful of, “modern art,” here was a contemporary “painting” that was being hailed as even more of a breakthrough by the art world cognoscenti than Ulysses had been by their literary counterparts. The public reaction to the first showing of The Large Glass may conceivably have further prodded Joyce as he started Finnegans Wake. This fits the picture of energetically competing twins.

As to “The Ballad of Persse O’Reilly” itself, the name, according to McHugh’s Annotations to Finnegans Wake, refers simultaneously to “Pearse & O’Rahilly,” figures in Dublin’s Easter Rising against the British in 1916, and to the French word perce-oreille, “earwig,” a small elongate insect with a pair of pincerlike appendages protruding from the rear of its abdomen. Folklore has it that earwigs can enter the head through an ear and feed on the brain. I believe that Joyce may be connecting the earwig with Duchamp, and also with Alfred Jarry, a writer who meant a great deal to both of them. To some extent all geniuses “feed,” as it were, on the brains of earlier geniuses, but Jarry and to a lesser degree Duchamp made a point of mentioning their progenitors.

click to enlarge

Figure 1

Marcel Duchamp, L.H.O.O.Q.

A close reading of Finnegans Wake shows Joyce doing likewise: the pincerlike appendages protruding from the earwig’s rear may relate both to Jarry’s homosexual braggadocio and to Duchamp’s notorious phrase “Elle a chaud au cul” (She has a hot ass), the French pronunciation ofL.H.O.O.Q. (Fig. 11), the title carefully lettered at the bottom of Duchamp’s mustachioed and goateed Mona Lisa of 1919. Like many works from this period in Duchamp’s work, L.H.O.O.Q. was credited to, and signed by, his alter ego, Rrose Sélavy, a character who was, according to her creator, an old whore. A calling card that Duchamp designed for her advertised that she was an Expert in precision ass and glass work. For Joyce, of course, the earwig is also a reference to H. C. Earwicker, the “hero” of Finnegans Wake.(Still again on the subject of parallels, Duchamp used one of the world’s most famous works of visual art as the point of departure with L.H.O.O.Q.; Joyce used one of the world’s most famous works of literary art as the point of departure with Ulysses.)

The “Ballad” continues,

Have you heard of one Humpty Dumpty / How he fell with a roll and a rumble / And curled up

like old Lord Olofa “Crumple / By the butt.

of the Magazine Wall, / (Chorus) Of the Magazine Wall, / Hump, helmet and all?

He was one time our King of the Castle

/ Now he’s kicked about like a rotten old parsnip. / And from Green street he’ll be sent by order of His Worship /

To the penal

jail of Mountjoy / (Chorus) To the jail of mountjoy!/Jail him and joy.

He was fafafather of all schemes for to bother us

Slow coaches and immaculate contraceptives

for the populace, / Mare’s milk for the sick,

seven dry Sundays a week, / Openair love and religious reform, / (Chorus) And religious reform, / Hideous in form.

Arrah, why, says you, couldn’t he manage it?/ I’ll go bail,

my fine dairyman darling, / Like the bumping bull of the Cassidys / All your butter is in your horns.

/ (Chorus) His butter is in his horns. / Butter his horns!

(Repeat) Hurrah there, Hosty, frosty Hosty, change that shirt on ye, / Rhyme the rann, the king of all ranns!

Balbaccio, balbuccio!

We had chaw chaw chops,

chairs, chewing gum, the chickenpox and china chambers

Universally provided by this soffsoaping salesman.

Small wonder He’ll Cheat E’erawan

our local lads nicknamed him / When Chimpden first took the floor / (Chorus) With his bucketshop store

Down Bargainweg, Lower.

So snug he was in his hotel premises sumptuous

But soon we’ll bonfire all this trash, tricks and trumpery

And ‘tis short till sheriff Clancy’ll be winding up his unlimited company

With the bailiff’s bom at the door, / (Chorus) Bimbam at the door. / Then he’ll bum no more.

. . . Lift it, Hosty, lift it, ye devil ye! Up with the rann, the rhyming rann!

The first draft has “lay low” instead of “curled up”

The first draft has “back” instead of “butt.”

“Hump, helmet and all? inserted in 1927.

Duchamp was a chess fanatic, at one time considered the strongest player in France. He played constantly with Joyce’s friend Beckett.

“He’ll be sent” is missing from the first draft.

“penal” was inserted in 1927.

In 1923 Duchamp made a “Wanted” poster picturing his own face, both in full and in profile

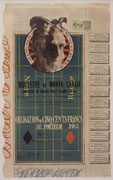

In his first draft of this section, written in 1923, Joyce wrote here “He had schemes in his head for to bother us.” In making this change Joyce may have had in mind the many letters Duchamp sent between 1924 and 1927 (Joyce could have heard about them from Reynolds) trying to sell, at 500 francs each, copies of his Monte Carlo Bond (Fig. 12), “a standard financial document . . . so heavily doctored that it could hardly be called a readymade.” Thirty were issued, hand-signed by Duchamp and his fictional alter ego Rrose Sélavy; prospective purchasers were offered an annual dividend of 20 percent on their investment. Gestures like these made Breton and others worry about Duchamp’s

mental condition: “How could a man so intelligent”—for Breton the most profoundly original mind of the century—“devote his time and energy to such trivialities?”

Jarry,in The Virgin and the Mannekin-Pis; (references to the famous Mannekin-Pis statue in Brussels appear regularly in the Wake), speaks of Father Prout’s “magnificent canonical invention: the Suppository Virgin.” In the same section he describes “various hydraulic and intimate mechanisms guaranteeing to devout ladies the birth of male offspring, or if so desired their nonbirth.”

for the populace, / Mare’s milk for the sick,

Jarry writes, “There are, furthermore, those who drink that [miraculous] water”—the pilgrims taken by “special trains” to “Lourdes water” for “poorer people.”

Possibly a reference to Duchamp’s Wanted: $2,000 Reward poster.

Burrus (butter), brother of Caseous.

This entire verse was an addition of 1927. McHugh: “It balbo: stuttering / It –accio: pejorative suffix / It –uccio: diminutive suffix.” Joyce is obviouslycalling someone a no-good little stutterer, a possible reference to Duchamp’s notes and puns.

McHugh: “chow chow chop: last lighter containing the sundry small packages to fill up a ship.” This may refer to the sundry items that Duchamp by 1927 had dubbed his Readymade works of art, which he was continually trying to sell; or to Duchamp’s and Lydie’s wedding gifts, “a daunting assortment of lamps, vases, and tableware” that filled several long tables. Joyce could have heard about this elaborate and very public church wedding from more than one source: his friend Reynolds was still in love with Duchamp, and Man Ray, who had photographed Joyce in 1922, was in attendance with his movie camera to film the happy couple, and was with them socially on a regular basis in the period after their marriage.

Duchamp’s Fountain, 1917, was a urinal made of china—large cousin to a chamberpot?

Duchamp was trying to sell copies of his Monte Carlo Bond, with its Man Ray portrait of him with shaving-soap horns and beard. This is first of all a reference to HCE—H. C. Earwicker, father

of Annalivia and of Shem and Shaun, who are also known as Burrus and Caseous, in Finnegans Wake. If this interpretation is correct, “He’ll cheat everyone” would fit Duchamp and his Monte

Carlo Bond scheme./ McHugh: “U.S. Sl[ang] bucketshop: unauthorized stockbroker’s

office.The text on Duchamp’s 1923 Wanted/$2,000 Reward (Fig.13) poster reads: “For information leading to the arrest of George W. Welch, alias Bull, alias Pickens etcetry, etcetry.Operated Bucket Shop in New York under name HOOKE, LYON and CINQUER. Height about 5 feet 9 inches. Weight about 180 pounds. Complexion medium, eyes same. Known also under name RROSE SELAVY.”

/This entire verse was an addition of 1927. Within weeks of his marriage, Duchamp rented a hotel room to work in. “He began spending more and more time in his hotel room. At home he was often lost

in silent meditation, looking out the window and smoking his pipe.”

/ McHugh: “Sl[ang] trash & trumpery: rubbish.”This may again be a reference to Duchamp’s Readymades, or to the gifts he received at his wedding.

“Bum” perfectly fits Joyce’s view of Duchamp, and perhaps of himself as well: both men had to do plenty of hustling, and both were reliant on wealthy women.

Perhaps a reference to Duchamp with two horns and a pointy beard in the photograph on Monte Carlo Bond.

click images to enlarge

Figure 12

Marcel Duchamp, Monte Carlo Bond,1924

Figure 13

Marcel Duchamp, Wanted/$2,000 Reward, 1923

Both Duchamp and Joyce are indebted to the eccentric turn-of-the-century poet and playwright Jarry. As mentioned, Breton summed up that writer’s contribution with this remark: “We maintain that beginning with Jarry . . . the differentiation long considered necessary between art and life has been challenged, to wind up annihilated as a principle.”The references to Duchamp in the Wake repeatedly seem intermingled with references to Jarry, who, like Duchamp in his Rrose Sélavy persona, was known to wear women’s clothes. He also boasted of both homosexual and heterosexual prowess.

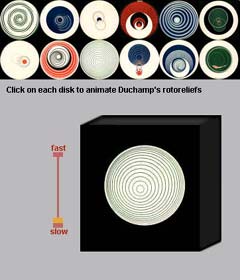

Further phrases in “The Ballad of Persse O’Reilly” that may refer to Rrose, with her calling card boasting “Specialist in precision ass and glass work,” and to Jarry, include “Our rotorious [Duchamp’s “rotoreliefs”?] hippopopotamuns [“G[erman] Popo: buttocks”] / When some bugger let down the backdrop of the omnibus / And he caught his death of fusiliers, / (Chorus) With his rent in his rears. / Give him six years.”

Afterword

You know he’s peculiar, that eggschicker, with the smell of old woman off him, to suck nothing of his switchedupes. M.D. made his ante mortem for him.

—James Joyce, Finnegans Wake

The section of Finnegans Wake containing these two sentences was revised for publication in transition no. 11, issued in February 1928. “M.D.” may refer in part to Marcel Duchamp. (It may also refer to Jonathan Swift, a frequent presence in the Wake: “M.D.”—“My dear”—was Swift’s abbreviation in letters to Stella, a major love of his life.) “Eggschicker,” from “chicker, to chirp as a cricket” (OED), is a word consistent with my reading of various sections of the Wake in which Joyce seems to be poking fun at Duchamp’s writing efforts. The idea of stuttering recurs (a cricket repeats its chirp), being repeatedly associated with Vico and others; here it may refer to Duchamp’s magazine rongwrong, and to the numerous repetitions in his notes.

“The smell of old woman off him…”: Here I recall Duchamp’s description of Rrose Sélavy as “an old whore.” “. . . to suck nothing of his switchedupes.” Duchamp in drag as Rrose. M.D. made his ante mortem for him. “L. ante mortem: before death.”This may be an inversion, a device beloved by Jarry, Joyce, and Duchamp. The “his” here may refer to Jarry, since the section contains many allusions to Jarry, according to my reading; if so, the inversion would translate “M.D. made Jarry’s ‘after death’ for him” into “M.D. made Jarry’s ‘afterlife’ for him,” a comment on Duchamp’s repeated trips to the well of Jarry-esque imagery—as if Duchamp had made Jarry immortal.

Admittedly, this is only one of numerous interpretations that come to mind. It brings to mind Joyce’s famous comment that his Finnegans Wake would keep the scholars busy for a thousand years.

There are sections of Finnegans Wake in which Duchamp does not seem on the scene as a character, yet in which multiple isolated allusions correspond to words and imagery from his works. Jarry imagery often lurks nearby. Between page 526, line 24, and page 527, line 25, for example, we find:

526.24: it was larking in the trefoll of the furry glans with two stripping baremaids, StillaUnderwood and Moth Mac Garry. The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even is the formal title of Duchamp’s Large Glass; his Traveller’s Folding Item, 1916, is an Underwood typewriter cover. Regarding “Moth McGarry,” a famous, highly poetic section in Jarry’s book The Supermale offers a graphic symbolist version of sexual intercourse by picturing a large death’s head moth that took no notice of a lamp but “went seeking . . . its own shadow . . . , banging it again and again with all the battering rams of its hairy body: whack, whack, whack.”

527.03: Listenest, meme mearest! The French version of The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even is La Mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même.

527.07 even under the dark flush of night. The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even.

527.09: Strip Teasy up the stairs. The Bride Stripped Bare. . . . The best-known work of Duchamp’s early years as a painter is surely Nude Descending a Staircase, made in two versions of 1911 and 1912 respectively. “…upthe stairs.” could be another simple inversion.

527.18: under nue charmeen. Nue, the French for “naked,” again recalls The Bride Stripped Bare . . . / La Mariée mise à nu. . . .

527.21: Blanchemain, idler. . . . Listen, meme sweety. MD See 160.3. The name “Professor Ciondolone,” we have seen, derived from the Italian for “idler,” according to our reading refers to Duchamp. “Meme” again refers to The Large Glass.

527.24: It’s meemly us two, meme idoll. The Large Glass.

527.25: meeting me disguised, Bortolo mio. In Beaumarchais’s play The Marriage of Figaro, and in the related operas by Mozart, Paisiello, and Rossini, Dr. Bortolo is a bachelorwho wants a bride.

Duchamp said, “Eroticism is a subject very dear to me. . . . In fact, I thought the only excuse for doing anything was to introduce eroticism into life. Eroticism is close to life, closer than philosophy or anything like it; it’s an animal thing that has many facets and is pleasing to use, as you would use a tube of paint.”

Duchamp’s notes from 1912–14 for The Large Glass center on love play and sexual intercourse between humanlike machines, and reveal just how dear eroticism was to the artist. The artist writes, for example,

The Bride is basically a motor. . . . The motor with quite feeble cylinders is a superficial organ of the Bride; it is activated by the love gasoline, a secretion of the Bride’s sexual glands and by the electric sparks of the stripping. (to show that the Bride does not refuse this stripping by the bachelors, even accepts it since she furnishes the love gasoline and goes so far as to help toward complete nudity by developing in a sparkling fashion her intense desire for the orgasm.

Published literature of the period did not talk this way, and unfettered pornography would have used an entirely different vocabulary. These notes were pioneering in more ways than one.

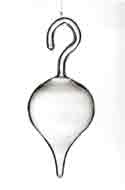

click to enlarge

Figure 14

Marcel Duchamp, Given: 1. The Waterfall / 2. The Illuminating Gas, 1946-66

Before its abrupt transformation into an art object, Duchamp’s upended urinal, Fountain, had been a gracefully curvy receptacle for male effusions. The title L.H.O.O.Q., we have seen, which he gave his Mona Lisa with added mustache and goatee, corresponds to the French for “She has a hot ass,” a loose translation of “There is fire down below.” The name of Duchamp’s famous female alter ego, Rrose Sélavy, who made her debut in 1921, is based on the phraseEros c’est la vie (Eros is life). Her pronouncements include, “Have you already put the hilt of the foil in the quilt of the goil” and “An incesticide must sleep with his mother before killing her.” The medium of Paysage fautif, 1946, is semen on Astralon. In theUntitled Original for Matta’s Box in a Valise, 1946, pubic hair is taped to paper. Female Fig Leaf, 1950, Wedge of Chastity, 1954, and the posthumously revealed Etant donnés . . . (Fig. 14) all feature casts supposedly made from a vagina, while Objet D’art, 1951, is decidedly phallic.

Joyce’s writing too was famously erotic, to the point where Ulysses was restricted in its distribution. Erotic and scatological passages can be found without too much effort on every page of Finnegans Wake.Molly’s erotic soliloquy, the unpunctuated tour de force with which Ulysses ends, was on its own to a large extent responsible for his early fame among the general public; and in the “Bloom in Nighttown” section (Sirens) of Ulysses, creative abandon reaches an erotic pitch reminiscent of Jarry, Rabelais, and The Thousand and One Nights.

Other parallels: Ellmann writes: ‘Joyce had been preparing himself to write Ulysses since 1907. It grew steadily more ambitious in scope and method, and represented a sudden outflinging of all he had learned as a writer up to 1914.’By way of coincidence, Alfred Jarry, who I argue was a strong unacknowledged source for Joyce, died in 1907 (at the age of 34). And in 1914, Duchamp wrote his famous ‘formula’ for Art: Arrhe est ‘a art que merdre est a merde:

| arrhe = |

merdre. |

| art |

merde |

An English translation might read: ‘Deposit is to art as shitte is to shit.’ Jarry’s ‘merdre’ is the only word not found in any dictionary. Given Duchamp’s extreme interest in the erotic, a likely interpretation would be, ‘My way of saying fucking corresponds to everyone else’s way of saying art as Jarry’s way of saying shit corresponds to everyone else’s way of saying shit’ – or more succinctly, ‘My fucking is to your art as Jarry’s shit is to your shit’.

We have seen in Joyce’s 1909 letters to Nora that Joyce was avidly coprophilic. Joyce scholar Clive Hart states, ‘There can be no denying that Joyce found everything associated with evacuation unusually pleasurable…’In Finnegans Wake Kate’s monologue ends with this passage: ‘And whowasit youwasit propped the pot in the yard and whatinthe nameofsen lukeareyou rubbinthe sideofthe flureofthe lobbywith. Shite! will you have a plateful? Tak.’Later in the same work we find Joyce’s verbal version of his own thumb-nosing drawing that we have reproduced at the top of this essay: ‘…kissists my exits’.

Duchamp’s urinal-as-art, Fountain, 1917, recalls Joyce’s earlier distillations of the erotic and scatological scrawls found on ‘the oozing wall of a urinal’.In Ulysses, there is this famous exchange: ‘-When I makes tea I makes tea, as old mother Grogan said. And when I makes water I makes water.’

‘-By Jove, it is tea, Haines said.’

‘Buck Mulligan went on hewing and wheedling’:

‘-So I do, Mrs. Cahill, says she. Begob, ma’am, says Mrs. Cahill, God send you don’t make them in the one pot. (Joyce’s italics.)

And lastly, in Finnegans Wake, Earwicker and Shaun complete an act of communion with the transubstantiated urine of the goddess Anna – daughter of the former, sister of the latter –:‘…when oft as the souffsouff blows her peaties up and a claypot wet for thee, my Sitys, and talkatalka tell Tibbs has eve…’

Notes

[1] James Joyce, Finnegans Wake, New York: Penguin, 1976 (1939).

[2] In this—but not solely in this—there is a common precedent in the eccentric turn-of-the-century French symbolist poet/playwright Alfred Jarry (1873–1907). Jarry’s strong effect on both James Joyce and Marcel Duchamp is the subject of six earlier essays by this writer, two for this journal: “Duchamp on the Jarry Road,” Artforum, September 1992; Jarry, Joyce, Duchamp and Cage, Catalogue for the Venice Biennale, 1993; William Anastasi with Michael Seidel, “Jarry in Joyce: A Conversation,” Joyce Studies Annual, 1995; “Jarry in Duchamp,” New Art Examiner, October 1997; “Jarry and l’Accident of Duchamp” in: Tout Fait: The Marcel Duchamp Studies Online Journal, vol. 1, nr. 1 (December 1999); and “Jarry, Joyce, Duchamp and Cage” (rev. ed., in English, of the Italian 1993 Venice Biennale essay, with additions), in: Tout Fait: The Marcel Duchamp Studies Online Journal, vol. 1, nr. 2 (May 2000).

[2] In this—but not solely in this—there is a common precedent in the eccentric turn-of-the-century French symbolist poet/playwright Alfred Jarry (1873–1907). Jarry’s strong effect on both James Joyce and Marcel Duchamp is the subject of six earlier essays by this writer, two for this journal: “Duchamp on the Jarry Road,” Artforum, September 1992; Jarry, Joyce, Duchamp and Cage, Catalogue for the Venice Biennale, 1993; William Anastasi with Michael Seidel, “Jarry in Joyce: A Conversation,” Joyce Studies Annual, 1995; “Jarry in Duchamp,” New Art Examiner, October 1997; “Jarry and l’Accident of Duchamp” in: Tout Fait: The Marcel Duchamp Studies Online Journal, vol. 1, nr. 1 (December 1999); and “Jarry, Joyce, Duchamp and Cage” (rev. ed., in English, of the Italian 1993 Venice Biennale essay, with additions), in: Tout Fait: The Marcel Duchamp Studies Online Journal, vol. 1, nr. 2 (May 2000).

[3] See Anne D’Harnoncourt and Kynaston McShine, eds., Marcel Duchamp (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1973), p. 18.

[3] See Anne D’Harnoncourt and Kynaston McShine, eds., Marcel Duchamp (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1973), p. 18.

[4] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Calvin Tomkins, The Bride and the Bachelors (New York: Penguin, 1965), p. 28.

[5] Calvin Tomkins, The Bride and the Bachelors (New York: Penguin, 1965), p. 28.

[6] André Breton, quoted in Roger Shattuck, The Banquet Years: The Origins of the Avant-Garde in France, 1885 to World War I (New York: Vintage Books, 1968), p. 217.

[6] André Breton, quoted in Roger Shattuck, The Banquet Years: The Origins of the Avant-Garde in France, 1885 to World War I (New York: Vintage Books, 1968), p. 217.

[7] Richard Ellmann, James Joyce (New York: Oxford UP, 1959), p. 608.

[7] Richard Ellmann, James Joyce (New York: Oxford UP, 1959), p. 608.

[8] Ibid., p. 3.

[8] Ibid., p. 3.

[9] Ibid., p. 5.

[9] Ibid., p. 5.

[10] Joyce, quoted in Ellmann, James Joyce, p. 5.

[10] Joyce, quoted in Ellmann, James Joyce, p. 5.

[11] Irene E. Hofmann. Mary Reynolds and the Spirit of Surrealism (Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, 1996), p. 139.

[11] Irene E. Hofmann. Mary Reynolds and the Spirit of Surrealism (Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, 1996), p. 139.

[12] Ellmann, James Joyce, p. 662.

[12] Ellmann, James Joyce, p. 662.

[13] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid., p. 559.

[14] Ibid., p. 559.

[15] Michel Sanouillet (ed.), introduction, in The Salt Seller: The Writings of Marcel Duchamp (New York: Oxford UP, 1973), p. 6.

[15] Michel Sanouillet (ed.), introduction, in The Salt Seller: The Writings of Marcel Duchamp (New York: Oxford UP, 1973), p. 6.

[16] Ibid., p. 19.

[16] Ibid., p. 19.

[17] Joyce, quoted in Ellmann, James Joyce, p. 559

[17] Joyce, quoted in Ellmann, James Joyce, p. 559

[18] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Joyce, quoted in Ellmann, James Joyce, p. 702.

[19] Joyce, quoted in Ellmann, James Joyce, p. 702.

[20] Joyce, quoted in Ellmann, James Joyce, p. 648.

[20] Joyce, quoted in Ellmann, James Joyce, p. 648.

[21] Ibid., p. 559.

[21] Ibid., p. 559.

[22] Susan Glover Godlewski, “Warm Ashes: The Life and Career of Mary Reynolds,” in: Mary Reynolds and the Spirit of Surrealism (Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, 1996), p. 108.

[22] Susan Glover Godlewski, “Warm Ashes: The Life and Career of Mary Reynolds,” in: Mary Reynolds and the Spirit of Surrealism (Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, 1996), p. 108.

[23] See Arturo Schwarz, The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp (New York: Delano Greenidge, 2002), p. 467.

[23] See Arturo Schwarz, The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp (New York: Delano Greenidge, 2002), p. 467.

[24] For Samuel Beckett, Joyce was a revered father figure while Duchamp was a friend closer to his own age, as well as a constant chess partner. Beckett “enjoyed Marcel Duchamp, who lived near him. [Mel Gussow] commented on Duchamp’s found objects, such as the urinal he exhibited as a work of art. Beckett laughed: ‘A writer could not do that.’” Mel Gussow, Conversations with and about Samuel Beckett (New York: Grove Press, 1996), p. 47. In 1981 Beckett “spoke [to a new young friend, Arnold Bernold] of the days before . . . recognition had descended on him, of Joyce with undiminished reverence, of Marcel Duchamp, of his early days in Paris.” Anthony Cronin, Samuel Beckett: The Last Modernist (New York: Da Capo, 1997), p. 573.

[24] For Samuel Beckett, Joyce was a revered father figure while Duchamp was a friend closer to his own age, as well as a constant chess partner. Beckett “enjoyed Marcel Duchamp, who lived near him. [Mel Gussow] commented on Duchamp’s found objects, such as the urinal he exhibited as a work of art. Beckett laughed: ‘A writer could not do that.’” Mel Gussow, Conversations with and about Samuel Beckett (New York: Grove Press, 1996), p. 47. In 1981 Beckett “spoke [to a new young friend, Arnold Bernold] of the days before . . . recognition had descended on him, of Joyce with undiminished reverence, of Marcel Duchamp, of his early days in Paris.” Anthony Cronin, Samuel Beckett: The Last Modernist (New York: Da Capo, 1997), p. 573.

[25] Joyce, quoted in Ellmann, James Joyce., p. 744.

[25] Joyce, quoted in Ellmann, James Joyce., p. 744.

[26] Marcel Duchamp, in Surrealism and Its Affinities: The Mary Reynolds Collection, a bibliography compiled by Hugh Edwards, (Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, 1956), p. 6.

[26] Marcel Duchamp, in Surrealism and Its Affinities: The Mary Reynolds Collection, a bibliography compiled by Hugh Edwards, (Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, 1956), p. 6.

[27] The only other female, as mentioned by Gussow as being in Joyce’s “own circle,” is Nancy Cunard; in Anthony Cronin, Samuel Beckett: The Last Modernist, p. 573. Only one other close female friend of Joyce’s, Nancy Cunard, is described as “close” in this collection of conversations; see p. 47.

[27] The only other female, as mentioned by Gussow as being in Joyce’s “own circle,” is Nancy Cunard; in Anthony Cronin, Samuel Beckett: The Last Modernist, p. 573. Only one other close female friend of Joyce’s, Nancy Cunard, is described as “close” in this collection of conversations; see p. 47.

[28] Deirdre Bair, Samuel Beckett (London: Harcourt, Brace & Jovanovich, 1978), p. 68.

[28] Deirdre Bair, Samuel Beckett (London: Harcourt, Brace & Jovanovich, 1978), p. 68.

[28A] Anthony Cronin, Samuel Beckett (New York, Da Capo, 1977), p. 311.

[28A] Anthony Cronin, Samuel Beckett (New York, Da Capo, 1977), p. 311.

[28B] Deirdre Bair, Samuel Beckett, p. 276.

[28B] Deirdre Bair, Samuel Beckett, p. 276.

[29] Deirdre Bair, Samuel Beckett, pp. 465-467.

[29] Deirdre Bair, Samuel Beckett, pp. 465-467.

[30] Calvin Tomkins, Duchamp (New York: Henry Holt, 1996), p. 257.

[30] Calvin Tomkins, Duchamp (New York: Henry Holt, 1996), p. 257.

[31] Henri-Pierre Roché, quoted in ibid., p. 258.

[31] Henri-Pierre Roché, quoted in ibid., p. 258.

[32] Ibid.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Ellmann, James Joyce, p. 633.

[33] Ellmann, James Joyce, p. 633.

[34] Joyce, quoted in Brenda Maddox, Nora (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1998), p. 66.

[34] Joyce, quoted in Brenda Maddox, Nora (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1998), p. 66.

[35] Joyce, quoted in p. 631

[35] Joyce, quoted in p. 631

[36] Nora Joyce, quoted in Ellmann, James Joyce (rev. ed., 1982), p. 700.

[36] Nora Joyce, quoted in Ellmann, James Joyce (rev. ed., 1982), p. 700.

[37] Ellmann, James Joyce, p. 619.

[37] Ellmann, James Joyce, p. 619.

[38] Tomkins, Duchamp, p. 148.

[38] Tomkins, Duchamp, p. 148.

[39] Ibid, p. 149.

[39] Ibid, p. 149.

[40] Ellmann, James Joyce, p. 427.

[40] Ellmann, James Joyce, p. 427.

[41] Ibid., p. 569.

[41] Ibid., p. 569.

[42] Ibid., p. 494.

[42] Ibid., p. 494.

[43] Ibid., p. 569.

[43] Ibid., p. 569.

[44] Ibid., p. 661.

[44] Ibid., p. 661.

[45] Tomkins, Duchamp, p. 278.

[45] Tomkins, Duchamp, p. 278.

[46] Joyce, Finnegans Wake, pp. 126–216.

[46] Joyce, Finnegans Wake, pp. 126–216.

[47] Ellmann, James Joyce, (rev. ed., 1982), p. 545.

[47] Ellmann, James Joyce, (rev. ed., 1982), p. 545.

[48] Joyce, Finnegans Wake, p. 160.

[48] Joyce, Finnegans Wake, p. 160.

[49] Calvin Tomkins, Marcel Duchamp, p. 259.

[49] Calvin Tomkins, Marcel Duchamp, p. 259.

[50] I have explored Jarry’s influence on both Joyce and Duchamp in earlier articles; see Anastasi, Jarry, Joyce, Duchamp and Cage, and Anastasi and Seidel, “Jarry in Joyce: A Conversation.” Throughout the Wake I find Jarry referred to with near reverence. Joyce was an intimate friend of Léon Paul Fargue, who in his youth had been Jarry’s closest friend and probably his lover. (Some believe him to have been Jarry’s only lover.) Joyce would likely have heard all about Jarry from Fargue. A photograph of the “Déjeuner Ulysse” banquet, given by Adrienne Monnier in June 1929, shows Fargue sitting next to Joyce near the center of twenty-six guests. See Richard Ellmann, ed.,Letters of James Joyce Letters vol. III (NY: Viking, 1966), p. 193. Jarry’s Faustroll, with its intermittently incomprehensible narrative and numerous made-up words, is an obvious forerunner of the Wake. Jarry’s biographer Keith Beaumont, writing of Faustroll and other works of Jarry’s that followed the lead of Stéphane Mallarmé, says, “The result is at times something in the nature of a verbal delirium which, at one end of the literary spectrum, recalls the delight in words of Jarry’s other great mentor, Rabelais, and, at the other, looks forward to the Joyce ofFinnegans Wake and beyond.” Beaumont, Alfred Jarry: A Critical and Biographical Study (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1984), p. 303. Jarry published his Caesar Antichrist in 1895. Passages in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar are likely to have informed the Burrus and Caseous sections of Finnegans Wake. Shakespeare has Cassius say of Caesar, for example, “Why man, he doth bestride the narrow world / Like a Colossus; and we petty men / Walk under his huge legs, and peep about / To find ourselves dishonourable graves.” Julius Caesar I, ii, 134. Jarry in life was very short, but since Joyce loved inversion (as did Jarry and Duchamp), he could have seen the Colossus image as a humorous inversion once he had set on the idea of Brutus (Burrus) and Cassius (Caseous) as stand-ins for himself and Duchamp. Actually, for Joyce to picture Jarry as a powerful father (a colossus), with himself and Duchamp as underlings, is consistent with images of Jarry found elsewhere in the book. Again, Shakespeare has Caesar say of Cassius, “He reads too much; / He is a great observer, and he looks / Quite through the deeds of men; he loves no plays, / As thou dost, Antony; he hears no music; Seldom he smiles, and smiles in such a sort / As if he mock’d himself, and scorn’d his spirit, / That could be mov’d to smile at anything. / Such men as he be never at heart’s ease, / Whiles they behold a greater than themselves, / And therefore are they very dangerous.”( I, ii, 197) It was known that Duchamp – in contrast to Joyce – did not enjoy music. And just as Joyce was confident that no living writer could compare with himself, Duchamp behaved in a way that suggested a similar confidence in relation to other artists.

[50] I have explored Jarry’s influence on both Joyce and Duchamp in earlier articles; see Anastasi, Jarry, Joyce, Duchamp and Cage, and Anastasi and Seidel, “Jarry in Joyce: A Conversation.” Throughout the Wake I find Jarry referred to with near reverence. Joyce was an intimate friend of Léon Paul Fargue, who in his youth had been Jarry’s closest friend and probably his lover. (Some believe him to have been Jarry’s only lover.) Joyce would likely have heard all about Jarry from Fargue. A photograph of the “Déjeuner Ulysse” banquet, given by Adrienne Monnier in June 1929, shows Fargue sitting next to Joyce near the center of twenty-six guests. See Richard Ellmann, ed.,Letters of James Joyce Letters vol. III (NY: Viking, 1966), p. 193. Jarry’s Faustroll, with its intermittently incomprehensible narrative and numerous made-up words, is an obvious forerunner of the Wake. Jarry’s biographer Keith Beaumont, writing of Faustroll and other works of Jarry’s that followed the lead of Stéphane Mallarmé, says, “The result is at times something in the nature of a verbal delirium which, at one end of the literary spectrum, recalls the delight in words of Jarry’s other great mentor, Rabelais, and, at the other, looks forward to the Joyce ofFinnegans Wake and beyond.” Beaumont, Alfred Jarry: A Critical and Biographical Study (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1984), p. 303. Jarry published his Caesar Antichrist in 1895. Passages in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar are likely to have informed the Burrus and Caseous sections of Finnegans Wake. Shakespeare has Cassius say of Caesar, for example, “Why man, he doth bestride the narrow world / Like a Colossus; and we petty men / Walk under his huge legs, and peep about / To find ourselves dishonourable graves.” Julius Caesar I, ii, 134. Jarry in life was very short, but since Joyce loved inversion (as did Jarry and Duchamp), he could have seen the Colossus image as a humorous inversion once he had set on the idea of Brutus (Burrus) and Cassius (Caseous) as stand-ins for himself and Duchamp. Actually, for Joyce to picture Jarry as a powerful father (a colossus), with himself and Duchamp as underlings, is consistent with images of Jarry found elsewhere in the book. Again, Shakespeare has Caesar say of Cassius, “He reads too much; / He is a great observer, and he looks / Quite through the deeds of men; he loves no plays, / As thou dost, Antony; he hears no music; Seldom he smiles, and smiles in such a sort / As if he mock’d himself, and scorn’d his spirit, / That could be mov’d to smile at anything. / Such men as he be never at heart’s ease, / Whiles they behold a greater than themselves, / And therefore are they very dangerous.”( I, ii, 197) It was known that Duchamp – in contrast to Joyce – did not enjoy music. And just as Joyce was confident that no living writer could compare with himself, Duchamp behaved in a way that suggested a similar confidence in relation to other artists.

[51] Pierre Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp (New York: Viking, 1971), p. 79.

[51] Pierre Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp (New York: Viking, 1971), p. 79.

[52] Joyce, Finnegans Wake, pp. 44–47. “By end of 1923 notebook containing rough drafts of all the episodes in Part I except i and vi (pp. 30–125, 169–216) was probably filled.” Ellmann, James Joyce, p. 801. “In 1927 Joyce was revising Part I (pp. 3–216) for publication in transition.” Ibid., p. 802.

[52] Joyce, Finnegans Wake, pp. 44–47. “By end of 1923 notebook containing rough drafts of all the episodes in Part I except i and vi (pp. 30–125, 169–216) was probably filled.” Ellmann, James Joyce, p. 801. “In 1927 Joyce was revising Part I (pp. 3–216) for publication in transition.” Ibid., p. 802.

[52A] Ellmann, 1975, The Viking Press, NY, Selected Letters of James Joyce, p.181

[52A] Ellmann, 1975, The Viking Press, NY, Selected Letters of James Joyce, p.181

[52B] Ibid, p.184

[52B] Ibid, p.184

[53] Roland McHugh, Annotations to Finnegans Wake (rev. ed. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991), p. 44.

[53] Roland McHugh, Annotations to Finnegans Wake (rev. ed. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991), p. 44.

[54] See David Hayman, ed., A First-Draft Version of Finnegans Wake (Austin, TX: Texas UP, 1963), p. 66.

[54] See David Hayman, ed., A First-Draft Version of Finnegans Wake (Austin, TX: Texas UP, 1963), p. 66.

[55] “The crate containing The Large Glass—in storage since the closing of the Brooklyn Museum exhibition in early 1927—had been shipped from the Lincoln Warehouse to “The Haven,” [Katherine] Dreier’s country house . . . where she planned to have it permanently reinstalled. On opening the crate, however, the workmen had discovered that the two heavy glass panels . . . were shattered from top to bottom. Tomkins, Duchamp, p. 288.

[55] “The crate containing The Large Glass—in storage since the closing of the Brooklyn Museum exhibition in early 1927—had been shipped from the Lincoln Warehouse to “The Haven,” [Katherine] Dreier’s country house . . . where she planned to have it permanently reinstalled. On opening the crate, however, the workmen had discovered that the two heavy glass panels . . . were shattered from top to bottom. Tomkins, Duchamp, p. 288.

[56] Roland McHugh, Annotations to Finnegans Wake, p. 44.

[56] Roland McHugh, Annotations to Finnegans Wake, p. 44.

[57] Breton, quoted in Tomkins, Duchamp, p. 261.

[57] Breton, quoted in Tomkins, Duchamp, p. 261.

[58] Alfred Jarry, “The Virgin and the Mannekin-Pis,” in: Selected Works of Alfred Jarry (New York: Grove Press, 1965), p. 127.

[58] Alfred Jarry, “The Virgin and the Mannekin-Pis,” in: Selected Works of Alfred Jarry (New York: Grove Press, 1965), p. 127.

[59] Ibid.

[59] Ibid.

[60] McHugh, Annotations to Finnegans Wake, p. 45.

[60] McHugh, Annotations to Finnegans Wake, p. 45.

[61] Ibid.

[61] Ibid.

[62] Tomkins, Duchamp, p. 280.

[62] Tomkins, Duchamp, p. 280.

[63] McHugh, Annotations to Finnegans Wake, p. 46.

[63] McHugh, Annotations to Finnegans Wake, p. 46.

[64] Tomkins, Duchamp, p. 281.

[64] Tomkins, Duchamp, p. 281.

[65] McHugh, Annotations to Finnegans Wake, p. 46.

[65] McHugh, Annotations to Finnegans Wake, p. 46.

[66] Schwarz, The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp, pp. 703–4.

[66] Schwarz, The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp, pp. 703–4.

[67] Breton, quoted in Shattuck, The Banquet Years: The Origins of the Avant-Garde in France, 1885 to World War I, p. 217.

[67] Breton, quoted in Shattuck, The Banquet Years: The Origins of the Avant-Garde in France, 1885 to World War I, p. 217.

[68] McHugh, Annotations to Finnegans Wake, p. 47.

[68] McHugh, Annotations to Finnegans Wake, p. 47.

[69] Joyce, Finnegans Wake, p. 423.

[69] Joyce, Finnegans Wake, p. 423.

[70] McHugh, Annotations to Finnegans Wake, p. 423.

[70] McHugh, Annotations to Finnegans Wake, p. 423.

[71] Jarry, The Supermale, trans. Ralph Gladstone and Barbara Wright (New York: New Directions, 1964), p. 39.

[71] Jarry, The Supermale, trans. Ralph Gladstone and Barbara Wright (New York: New Directions, 1964), p. 39.

[72] Duchamp, in an interview with George H. Hamilton and Richard Hamilton, in “Art and Anti-Art,” BBC radio broadcast, London 1959. Quoted in Schwarz, The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp (London: Thames & Hudson, 1969), p. 80.

[72] Duchamp, in an interview with George H. Hamilton and Richard Hamilton, in “Art and Anti-Art,” BBC radio broadcast, London 1959. Quoted in Schwarz, The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp (London: Thames & Hudson, 1969), p. 80.

[73] Michel Sanouillet (ed.), Salt Seller: The Writings of Marcel Duchamp, p. 42.

[73] Michel Sanouillet (ed.), Salt Seller: The Writings of Marcel Duchamp, p. 42.

[74] This observation is backed up by years of highly pleasurable research by the present writer and the resultant book on the subject, Up Erogenously, copyright January 2003 (unpublished).

[74] This observation is backed up by years of highly pleasurable research by the present writer and the resultant book on the subject, Up Erogenously, copyright January 2003 (unpublished).

[75] Richard Ellmann : James Joyce, new revised edition, 1982, Oxford University Press NY, Oxford, Toronto. p. 357

[75] Richard Ellmann : James Joyce, new revised edition, 1982, Oxford University Press NY, Oxford, Toronto. p. 357

[76] Clive Hart, Structure and Motif in Finnegans Wake, 1962, Faber and Faber, London.

[76] Clive Hart, Structure and Motif in Finnegans Wake, 1962, Faber and Faber, London.

[77] Finnegans Wake, p.142

[77] Finnegans Wake, p.142

[78] Finnegans Wake, p.280

[78] Finnegans Wake, p.280

[79] Portrait of the Artist As a Young Man, p. 113

[79] Portrait of the Artist As a Young Man, p. 113

[80] Ulysses, p.17

[80] Ulysses, p.17

[81] Finnegans Wake, p. 117

[81] Finnegans Wake, p. 117

Figs. 1B, 3-14

©2003 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris. All rights reserved.