Intentions:

Logical and Subversive by Richard K. Merritt |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Symbolic Logic and Visualizing Concept in the Work of Marcel Duchamp The seemingly innate propensity of the human mind to binary, "this not that thinking" may be fruitfully illustrated by using symbolic logic in an interpretation of the intentions of Marcel Duchamp. With symbolic logic as a form of information or concept visualization one can demonstrate the difficulty and visual complexity of examining Duchamp's work using a deterministic system of equivalencies. First let us use the most oft sited interpretations of Duchamp's oeuvre and their corresponding significances and assign to each a variable. The following is by no means an exhaustive codification of the many interpretations of Marcel Duchamp's works it is essentially a categorization of a few of the major theories. A. The use of the "ready-made" or "found object" asserts that by altering the context of a commonplace object it can become art. D. The statement A allows that Duchamp in challenging the definition of the art object by exalting the primacy of the idea over the creative act he subverted the modernist convention of the artist/object and viewer relationships B. The work was an exploration of the mathematics of uncertainty pioneered by Henri Poincaré and the study of the fourth dimensional space theorized by Élie Jouffret (Traité Élémentaire de Géometrie à Quatre Dimensions 1903). H. The statement B. allows that Duchamp called into question the discipline boundaries between art and science and destroys the notion of the artist as creator of 'retinal art" or the aesthetic object. C. The work was engineered to be reassembled by the patron or viewer, who followed complex, often informed by chance, instructions. This process is evident in Duchamp's assemblage book works such as La Bôite Verte.

We will next

make a formula that contextualizes more precisely the relationship

between the upper level referent variables A, B and C (in this case

those variables that refer to the condition of Duchamp's work rather

than his intentions). Supplanting a corresponding lower case Greek

letters, A becoming a(alpha), B becoming b(beta), and C becomes g(gamma)

the following is the rule, universal quantifier or binding of variables

governing their relationships. (Fig. 8)

The next section of this exploration of the work of Marcel Duchamp through symbolic logic will determine the consistency of each of the condition/intention hypotheses. First we will examine the consistency of the argument A, if and only if, D: (Fig. 10)

The statement A if and only if D proves logically consistent. Next we have the hypothesis B, if and only if, H: (Fig. 11)

In short, Poincaré asserts that all quantifiable and qualifiable information pertaining to any phenomena can only be measured relative to other qualified and quantified data. As the first to elucidate this "principle of relativity" Poincaré discerned that all explicit information about any physical phenomena in motions is best expressed in the form of a probability. Poincaré's critique of determinism extends to other disciplines as well as he states, "The science of history is built out of bricks; but an accumulation of historical facts is no more a science than a pile of bricks is a house." This kind of reasoning is the bedrock of semiotics (meaning in language is ascertain through the relationship between the symbol and its meaning relative to the culture that produced it). It has also been used to critique symbolic logic. The discipline itself relies on abstract patterns, its meaning determined not from the symbols themselves but from the relationship between the marks and other patterns and more significantly cultural meanings. Duchamp's connection to logic is most clearly noted in two of his most significant areas of concern: chance and chess. As a chess master Duchamp was, on several occasions, a member of the French championship chess team. For Duchamp chess was an organized, integrated and ordered whole, composed of rule based interactions wherein outcomes were as influenced by unquantifiable elements such as guile or desire as by systematic reasoning. This led Duchamp to assert that complexity in any system was inherently non-deterministic. We see this questioning of aggregation, perhaps more clearly, in his use of chance in aesthetic production.

Duchamp's work Nude Descending a Staircase (1912) was first displayed at the Cubist Exhibition at the Damau Gallery in Barcelona and later at the Armory Show (New York, 1913). This painting took the observational cubist penchant of displaying an object from multiple spatial vantagepoints and added a temporal element by rendering a nude figure in motion. This work explored the conceptual possibility of 2d painting, which displayed and illustrates a 3 dimensional figure traversing time. The piece arrives at a visceral form of multi dimensional cognition. Partial inspired by his interest in chronophotography and the mathematics of Henri Poincaré Nude Descending a Staircase is perhaps his last clear attempt to use a traditional modality of retinal art to express a conceptual or gray matter art. It is also his first widely exhibited work to express his interest in the merger of science and art. His continued interest in multiple dimensions, though I cannot prove this, is probably where we may find the solution or at least a map to a clear understanding of his work. Though we may never have a concise definition of "what his work was about" Duchamp may have left us clues as to how we may begin to "make sense" of his intentions.

The piece is in fact, an original painting not a commercial postcard. The curious parallel and perpendicular lines on the back are in fact obscure instructions. Duchamp's fascination with rotation and relative vantagepoints indicates that a new dimension may be experienced through altering ones position relative to an object. When the postcard is turned 90º to the right the boats become an orthogonal rendering of deckchairs viewed from a bird's eye vantagepoint. The mysterious "random note" on the verso is a plea to adjust your perspective when viewing the postcard but also, when correlated with the image from the front the piece becomes a profound statement about the relationship between the second third and fourth dimensions. Like E. A. Abbot's famous book Flatland (1885) whose main character, a square, is shockingly introduced to the third dimension, Duchamp has demonstrated for us that one can examine from a three dimensional vantage point all sides of a two dimensional object. In turning the postcard we are taking a clearly two-dimensional image and viewing it from the third dimension wherein the objects in question become something entirely different. In postcard he begs the analogy: that when viewed from the fourth dimension a three-dimensional object may be seen from all sides. From years of singular interpretations of Duchamp's oeuvre art historians have safely ignored Duchamp's multiple interpretations: one obvious and the others subversive. When the work is proclaimed (by the artist himself) and interpreted as a "ready-made" the hidden intention with all of its possible significance is obscured. Duchamp disavowed

models of reasoning, which relied on singular definitions. This kind

of one or two-dimensional interpretation is inherently flawed when

attempting to ascertain his intentions. With this in mind, Duchamp's

work requires that any conceptual model of his intentions necessitates

three-dimensional thinking and thusly is well suited to three-dimensional

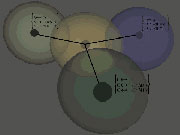

visualization. Immersive Experience and Concept Visualization As demonstrated, the use of symbolic logic as a means to visualizing concept in the work of Marcel Duchamp is extremely difficult. Though I have not examined the use of more advanced forms of symbolic logic (I am not a logician) it is apparent that the data, as envisaged, is not of the highest utility. The virtual reality

computer art piece Immersive Duchamp Concept World, presents

the theories concerning the artist's work. At the center of the virtual

space is the entrance point to the world. The immersant or

viewer may follow the map which branches off to various nodal points.

Each of these nodal points represents a single theory. From the vantagepoint

of the theory the immersant sees the other possible theories through

a fog and translucent sheets, they are barely visible, as the immersant/viewer

has chosen an alternate path (Fig. 15).

In Immersive Duchamp Concept World the immersant is also introduced

to various interactive media; readings of Duchamp's Notes as well

as to still images and animations of his work and to the writings

of Henri Poincaré. If the immersant chooses to fly above the object

it is from this vantagepoint the viewer sees all of the theories as

a totality (Fig. 16). This totality,

is essentially a relativistic rather than a fixed deterministic system

as the viewer governs the experience. This model for information visualization

does not stand in opposition to symbolic logic, however it does allow

a form of concept visualization that merges reason quantification,

qualification and the visceral. Conclusion The body of work produced by Marcel Duchamp was a programmatic, if playful, undermining of deterministic thinking. He demolished arbitrary discipline boundaries between artist scientist and mathematician. His clues to altering our perspective were equally pertinent to viewing and understanding his oeuvre as they were to viewing individual works of art. His implicit and explicit call for altering our vantagepoint relative to his intentions inherently calls into question modernist singular interpretations. Yet, through the use of concept visualization, we can create more exploratory modes of information visualization; modes which allow for simultaneous multiple dimensional thinking. In an immersive environment the viewer can experience a panorama of Duchamp's intentions, one that does not enforce strict rules of consistency, but nonetheless leads us to comprehension of a poly-dynamic yet visceral logic.

References

Boxer, S. "Taking

Jokes By Duchamp to Another Level of Art. "The New York Times

Clair, J. Sur Marcel Duchamp et la fin de l'art. Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 2000. D'Harnoncourt,

Anne & McShine, eds. Marcel Duchamp. Duchamp, M. Notes. Paris: Champs Flammarion- Centre d'art et de culture Georges Pompidou, 1999. Golding, J.

Duchamp: The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors. Gould, S. J. & Shearer, R. "Boats and Deck Chairs." Tout Fait: The Marcel Duchamp Studies Online Journal. 1.1 (Dec. 1000): Articles <http://www.toutfait.com/issues/issue_1/Articles/boat.html> Hodges, W. Logic.

Ifrah, G. The

Universal History of Numbers. Reichenbach,

H. Elements of Symbolic Logic. Scribner, C. "Henri Poincare and the principle of relativity." American Journal of Physics 32 (1963): 673. Tomkins, C.

The World of Marcel Duchamp 1887-1968. Williams, J. "Pata or Quantum: Duchamp and the end of Deterministic Physics", Tout Fait: The Marcel Duchamp Studies Online Journal. 2.3 (Dec. 2000): Articles <http://www.toutfait.com/issues/issue_3/Articles/williams/williams.html>

page

1 2 Figs.

13, 14

|